Lionel Stander was born in The Bronx, New York City, New York, to Russian–Jewish immigrants, the first of three children.

According to newspaper interviews with Stander, as a teenager he appeared in the silent film Men of Steel (1926), perhaps as an extra, since he is not listed in the credits.

During his one year at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he appeared in the student productions The Muse of the Unpublished Writer,[1] and The Muse and the Movies: A Comedy of Greenwich Village.

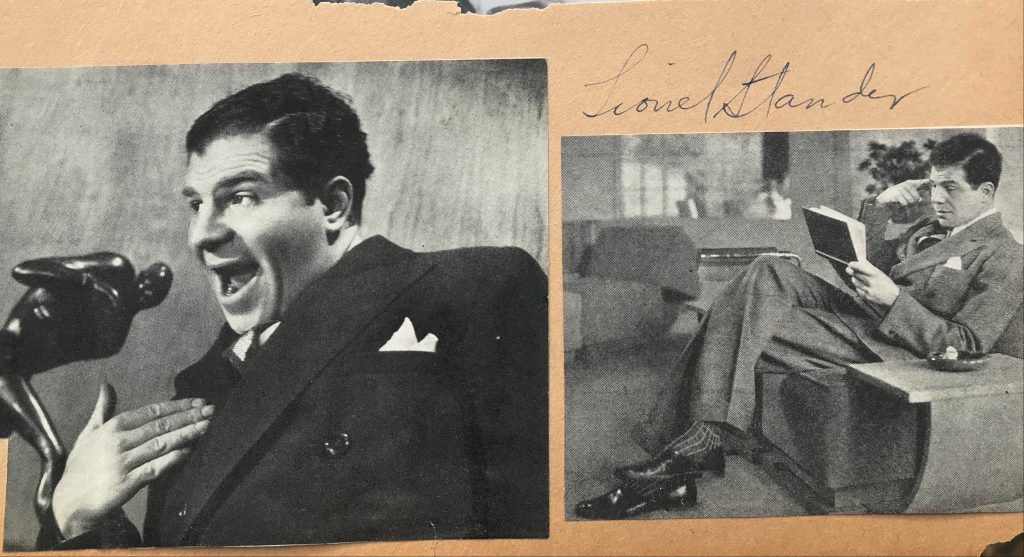

Career[edit]

Stander’s acting career began in 1928, as Cop and First Fairy in Him by E. E. Cummings, at the Provincetown Playhouse. He claimed that he got the roles because one of them required shooting craps, which he did well, and a friend in the company volunteered him. He appeared in a series of short-lived plays through the early 1930s, including The House Beautiful, which Dorothy Parker famously derided as “the play lousy”.[citation needed]

Early film roles[edit]

In 1932, Stander landed his first credited film role in the Warner–Vitaphone short feature In the Dough (1932), with Fatty Arbuckle and Shemp Howard. He made several other shorts, the last being The Old Grey Mayor (1935) with Bob Hope in 1935. That same year, he was cast in a feature, Ben Hecht‘s The Scoundrel (1935), with Noël Coward. He moved to Hollywood and signed a contract with Columbia Pictures. Stander was in a string of films over the next three years, appearing most notably in Frank Capra’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town(1936) with Gary Cooper, Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) playing Archie Goodwin, The League of Frightened Men (1937), and A Star Is Born (1937) with Janet Gaynor and Fredric March.[citation needed]

Radio roles[edit]

Stander’s distinctive rumbling voice, tough-guy demeanor, and talent with accents made him a popular radio actor. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was on The Eddie Cantor Show, Bing Crosby‘s KMH show, the Lux Radio Theater production of A Star Is Born, The Fred Allen Show,[2] the Mayor of the Town series with Lionel Barrymore and Agnes Moorehead, Kraft Music Hall on NBC, Stage Door Canteen on CBS, the Lincoln Highway Radio Show on NBC, and The Jack Paar Show, among others.

In 1941, he starred in a short-lived radio show called The Life of Riley on CBS, no relation to the radio, film, and television character later made famous by William Bendix. Stander played the role of Spider Schultz in both Harold Lloyd‘s film The Milky Way (1936) and its remake ten years later, The Kid from Brooklyn (1946), starring Danny Kaye. He was a regular on Danny Kaye’s zany comedy-variety radio show on CBS (1946–1947), playing himself as “just the elevator operator” amidst the antics of Kaye, future Our Miss Brooks star Eve Arden, and bandleader Harry James.[citation needed]

Also during the 1940s, he played several characters on The Woody Woodpecker and Andy Panda animated theatrical shorts, produced by Walter Lantz. For Woody Woodpecker, he provided the voice of Buzz Buzzard, but was blacklisted from the Lantz studio in 1951 and was replaced by Dal McKennon.

Strongly of communist ideology and pro-labor, Stander espoused a variety of social and political causes, and was a founding member of the Screen Actors Guild. At a SAG meeting held during a 1937 studio technicians’ strike, he told the assemblage of 2000 members: “With the eyes of the whole world on this meeting, will it not give the Guild a black eye if its members continue to cross picket lines?” (The NYT reported: “Cheers mingled with boos greeted the question.”) Stander also supported the Conference of Studio Unions in its fight against the Mob-influenced International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). Also in 1937, Ivan F. Cox, a deposed officer of the San Francisco longshoremen’s union, sued Stander and a host of others, including union leader Harry Bridges, actors Fredric March, Franchot Tone, Mary Astor, James Cagney, Jean Muir, and director William Dieterle. The charge, according to Time magazine, was “conspiring to propagate Communism on the Pacific Coast, causing Mr. Cox to lose his job”.[citation needed]

In 1938, Columbia Pictures head Harry Cohn allegedly called Stander “a Red son of a bitch” and threatened a US$100,000 fine against any studio that renewed his contract. Despite critical acclaim for his performances, Stander’s film work dropped off drastically. After appearing in 15 films in 1935 and 1936, he was in only six in 1937 and 1938. This was followed by just six films from 1939 through 1943, none made by major studios, the most notable being Guadalcanal Diary (1943).[citation needed]

Stander was among the first group of Hollywood actors to be subpoenaed before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1940 for supposed Communist activities. At a grand jury hearing in Los Angeles in August 1940—the transcript of which was shortly released to the press—John R. Leech, the self-described former “chief functionary” of the Communist Party in Los Angeles, named Stander as a CP member, along with more than 15 other Hollywood notables, including Franchot Tone, Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Clifford Odets and Budd Schulberg. Stander subsequently forced himself into the grand jury hearing, and the district attorney cleared him of the allegations.

Stander appeared in no films between 1944 and 1945. Then, with HUAC’s attentions focused elsewhere due to World War II, he played in a number of mostly second-rate pictures from independent studios through the late 1940s. These include Ben Hecht’s Specter of the Rose (1946); the Preston Sturges comedy The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) with Harold Lloyd; and Trouble Makers (1948) with The Bowery Boys. One classic emerged from this period of his career, the Preston Sturges comedy Unfaithfully Yours (1948) with Rex Harrison.

In March 1951, actor Larry Parks, after pleading with HUAC investigators not to force him to “crawl through the mud” as an informer, named several people as Communists in a “closed-door session”, which made the newspapers two days later. He testified that he knew Stander, but did not recall attending any CP meetings with him.

After that, Stander was blacklisted from TV and radio. He continued to act in theater roles, and played Ludlow Lowell in the 1952-53 revival of Pal Joey on Broadway and on tour.

Two years passed before Stander was issued the requested subpoena. Finally, in May 1953, he testified at a HUAC hearing in New York, where he made front-page headlines nationwide by being uproariously uncooperative, memorialized in the Eric Bentley play, Are You Now or Have You Ever Been. The New York Times headline was “Stander Lectures House Red Inquiry.”

An excerpt from that statement was engraved in stone for “The First Amendment Blacklist Memorial” by Jenny Holzer at the University of Southern California.

Other notable statements during Stander’s 1953 HUAC testimony:

Stander was blacklisted from the late 1940s until 1965; perhaps the longest period.

After that, Stander’s acting career went into a free fall. He worked as a stockbroker on Wall Street, a journeyman stage actor, a corporate spokesman—even a New Orleans Mardi Grasking. He didn’t return to Broadway until 1961 (and then only briefly in a flop) and to film in 1963, in the low-budget The Moving Finger (although he did provide, uncredited, the voice-over narration for the 1961 noir thriller Blast of Silence.)

Life improved for Stander when he moved to London in 1964 to act in Bertolt Brecht‘s Saint Joan of the Stockyards, directed by Tony Richardson, for whom he’d acted on Broadway, along with Christopher Plummer, in a 1963 production of Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. In 1965, he was featured in the film Promise Her Anything. That same year Richardson cast him in the black comedy about the funeral industry, The Loved One, based on the novel by Evelyn Waugh, with an all-star cast including Jonathan Winters, Robert Morse, Liberace, Rod Steiger, Paul Williams and many others. In 1966, Roman Polanski cast Stander in his only starring role, as the thug Dickie in Cul-de-sac, opposite Françoise Dorléac and Donald Pleasence.

Stander stayed in Europe and eventually settled in Rome, where he appeared in many spaghetti Westerns, most notably playing a bartender named Max in Sergio Leone‘s Once Upon a Time in the West. He played the role of the villainous mob boss in Fernando Di Leo‘s 1972 poliziottescho thriller Caliber 9. In Rome he connected with Robert Wagner, who cast him in an episode of It Takes a Thief that was shot there. Stander’s few English-language films in the 1970s include The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight with Robert De Niro and Jerry Orbach, Steven Spielberg’s 1941, and Martin Scorsese‘s New York, New York, which also starred De Niro and Liza Minnelli.

Stander played a supporting role in the TV film Revenge Is My Destiny with Chris Robinson. He played a lounge comic modeled after the real-life Las Vegas comic Joe E. Lewis, who used to begin his act by announcing “Post Time” as he sipped his ever-present drink.

After 15 years abroad, Stander moved back to the U.S. for the role he is now most famous for: Max, the loyal butler, cook, and chauffeur to the wealthy, amateur detectives played by Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers on the 1979–1984 television series Hart to Hart (and a subsequent series of Hart to Hart made-for-television films). In 1982, Stander won a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Series, Miniseries or Television Film.

In 1986, he became the voice of Kup in The Transformers: The Movie. In 1991 he was a guest star in the television series Dream On, playing Uncle Pat in the episode “Toby or Not Toby”. His final theatrical film role was as a dying hospital patient in The Last Good Time (1994), with Armin Mueller-Stahl and Olivia d’Abo, directed by Bob Balaban