Russ Conway obituary in “The Guardian” in 2000.

The honky-tonk pianist and composer Russ Conway, who has died of cancer aged 75, enjoyed a great British chart success in the late 1950s and early 1960s. His biggest hit was Side Saddle (1959). He emerged during a hiatus in popular music, before exportable British rock took hold, that produced a clutch of successful piano players, including Winifred Atwell and Liberace, who, along with Conway, were to influence the work of Elton John in later decades.

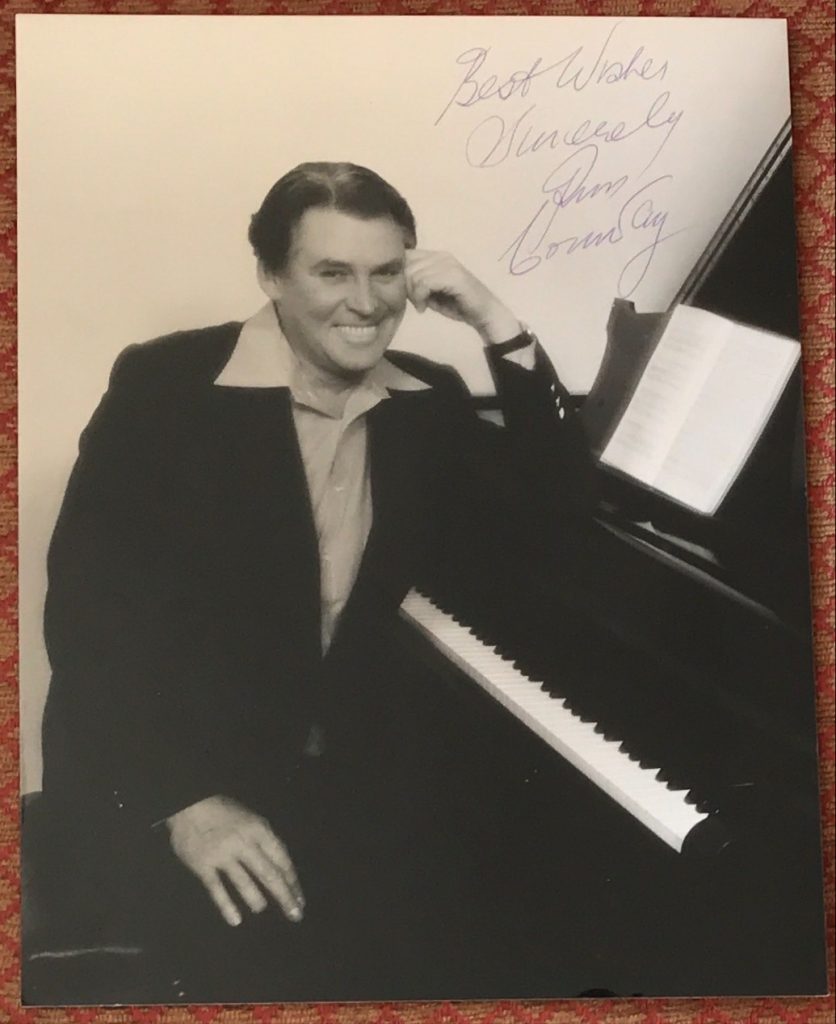

Conway was a particular favourite. Tall, anonymously handsome and with shining white teeth – this at a time when complicated bridgework was largely a stranger to British dentistry – he had a particular appeal to women. He sold more than 30m records, had 17 consecutive top-20 hits, his own television shows, mansions, Bentleys and Rolls-Royces. He was always embarrassed at being compared to Liberace, the white-fur-coated and smirking American pianist.

In fact, Conway’s and Liberace’s music and lifestyles were quite different. It was not just Conway’s looks that set him apart from the flamboyant American; his piano style was leaner, firmer and less pretentious, less nakedly appealing to blue-rinsed ladies. His glissandi were no less confident, but less self-indulgent, and he was equally as sure when handling A Nightingale Sang In Berkeley Square as Tiger Rag.

His lifestyle, too, though at one time luxurious by the cramped style of the times, was less pretentious, not reliant on screaming clothes; Conway favoured plain dark suits and ties, more in line with his humble background. Nor was he a natural in meeting the extravagant demands of showmanship, which, as a shy man, he always found stressful.

Throughout his life, he was prone to illnesses and accidents, which he saw as his body’s reaction against the tyranny of the piano. He fell, broke a hip and was paralysed for several days; he had strokes; he sliced off the top of a finger with a bread-slicer – something which, ironically, became a Conway signature as television cameras zoomed into his hands on the keyboard – and he smoked up to 80 untipped cigarettes a day.

Close on 70 years of age, he jammed a finger in the door of his Rolls-Royce, but he never agreed with the pundits who pensioned him off. A few months later in Bristol, he was busy entertaining a belated 50th anniversary tea-dance to celebrate Victory in Europe Day, where he nonchalantly peeled off the bandage from his wounded finger before attacking the keys.

Born in Bristol as Trevor Stanford, the name he retained for his composing work, Conway was the son of a mother who died when he was 14, but who had been an amateur pianist and contralto in her day. Unlike his two brothers, who had musical education but no talent, Conway had virtually no musical education, apart from a single boyhood lesson. His clerical-worker father put his son through secretarial college after the boy left school at 14, and then got him a job as a solicitor’s clerk. But, at 16, Conway made for the Merchant Navy training school and his first passage, on a Dutch freighter.

During the second world war, he earned the distinguished service medal in the Royal Navy for “gallantry and devotion to duty” in mine-sweeping in the Mediterranean. After four years in the RN, his long-running stomach ulcer saw him invalided out. The end of the war found him see-sawing between the Merchant Navy and dead-end jobs as a salesman, plumber’s mate and barman.

Then a friend suggested he stand in for a holidaying club pianist. He played in pubs and clubs, and was seen by the choreographer Irving Davies, who was so impressed that he asked him to play piano for stars at rehearsals. He worked for Dennis Lotis, Dorothy Squires and Gracie Fields. But it was when Conway made it to the Billy Cotton Band Show, a fixture on BBC radio and television in the 1950s and early 1960s, that the rumbustious bandleader persuaded him to loosen up his playing, and helped create the disciplined freedom of the mature Conway style.

It was not playing but composing that indirectly led him to fame. A musical he had written for the comedian Frankie Howerd, Mr Venus, was a write-off, but it led him to writing the score for a TV musical, Beauty And The Beast. For it, he had to write a last-minute tune for one brief scene set in a ballroom. Sitting in the rehearsal room, Conway wrote 16 bars as an olde-world gavotte and scribbled “Side Saddle” beside it in the margin.

Though it was to become virtually his signature tune, the music industry was, at first, blind to the piece’s potential. A publisher took all Conway’s music for Beauty And The Beast – except Side Saddle, which he dismissed as “too old-fashioned”. Another publisher, after its writer had honky-tonked it up, did not agree. Soon, Conway was a national figure, and China Tea, Roulette and Snowcoach followed.

In 1960, when he had his first television show, Russ Conway And A Few Friends, he was reputed to be earning £500 a week, then a huge sum, in record and sheet sales alone. He became an instantly recognisable face and sound, while the media found him politely evasive when discussing anything except his work. He moved from a basement flat in Maida Vale, where he personally answered his fan mail, to a mansion, where three full-timers did the job.

The music promoter who had called him “an atrocious pianist” was in a minority, but symbolised the stress Conway felt he was under. The stomach ulcer returned. In 1963, he had a nervous breakdown while playing at Scarborough, and then fell and fractured a hip, leaving him paralysed for three days; two years later, at only 38, he had the first of his strokes.

He had several times to give up playing, but never had to give up composing. He and his compositions were heard at seaside resorts and at theatres, including the London Palladium, long after his records had vanished from the charts.

At 65, Conway discovered he had cancer. Noting that others waiting to see specialists were either talkative and confident of surviving or silent and morose, he resolved to be part of the former group – and succeeded for many years. He lived on in Eastbourne and never married.

Russ Conway (Trevor Stanford), pianist and composer, born September 2 1925; died November 15 2000