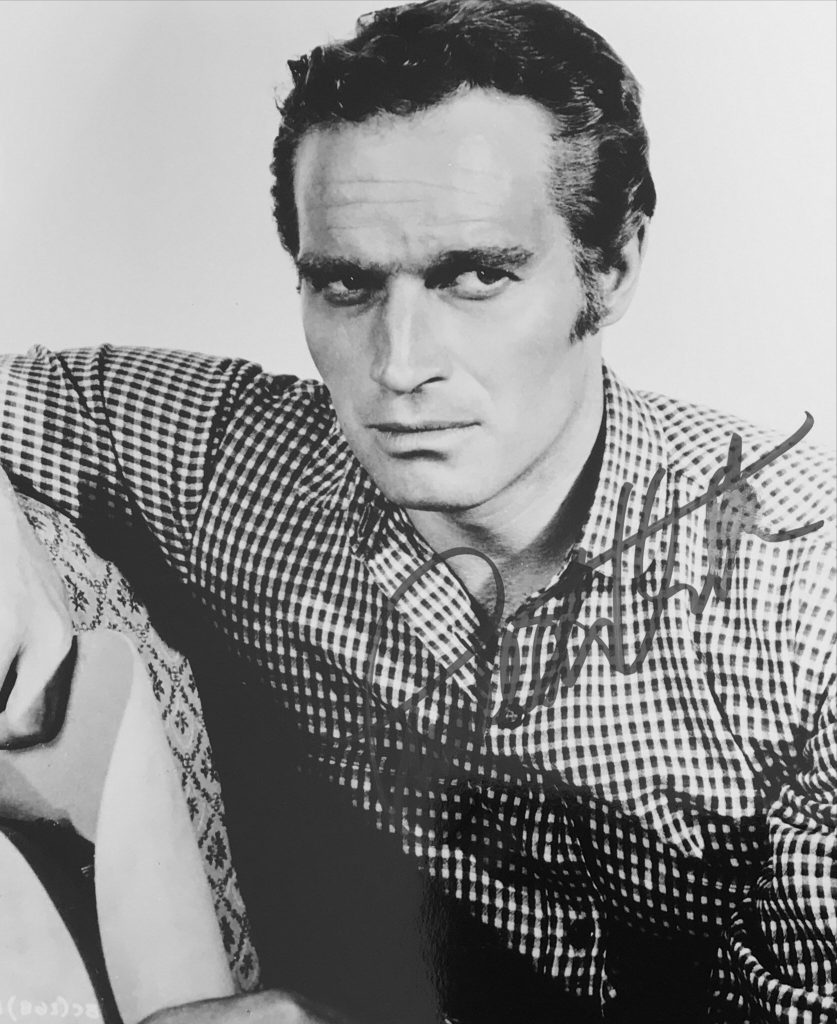

The actor Charlton Heston, who has died after suffering from Alzheimer’s possessed in abundance ambition, screen presence, a fine physique, chiselled jaw and an outstanding voice. Plus a liking for the classics and heroic characters, and a determination to survive. His professional survival lasted well over 50 years, and he famously played Ben-Hur, for which he won an Oscar, American presidents, Moses, General Gordon, Michelangelo and God (twice), alongside more mundane roles.

He had been active in civil rights issues in the 1950s, long involved with the Screen Actors Guild and with the American Film Institute. In the late 1960s his politics moved significantly to the right and his conservatism and support of the gun lobby left him open to considerable criticism. None of which seemed to worry him or modify his resolute opposition to political correctness.

No actor has made a screen debut more prescient than his. Aged just 18 he starred in Peer Gynt, in a silent version of Ibsen’s play, accompanied by Grieg’s music and given modest coherence by the use of intertitles. The youthful director, David Bradley, filmed his gangling, handsome star in wooded glades splashed by waterfalls, in scanty costumes. Seen today, it looks like the softest of soft porn.

Bradley made amends years later by casting Heston in a more suitable role as Mark Antony in a more coherent version of a great play, Julius Caesar (1950). The film reveals his star as a young man now matured into the serious, sturdy, bass- voiced actor who was to make a further 60 features, numerous TV movies and series, and be both a stage actor and director of distinction.

Heston was born Charles Carter in Chicago , and when his parents divorced and his mother remarried he took his stepfather’s name. He began acting at school, studied his craft at Northwestern University, made his extraordinary screen debut and soon after had his would-be career interrupted by the war. He served three years in the US Air Force as a B-25 radio operator and towards the end of his service finally persuaded his youthful sweetheart – Lydia Clarke – to marry him.

It proved a lifelong commitment, and she became the bedrock to his life and work. Although Lydia remained an actor, she largely forsook her career to be a wife, and mother to Fraser and Holly. However, during the immediate postwar years she and Chuck, as he has invariably been called, lived in New York and acted on stage there and throughout the country.

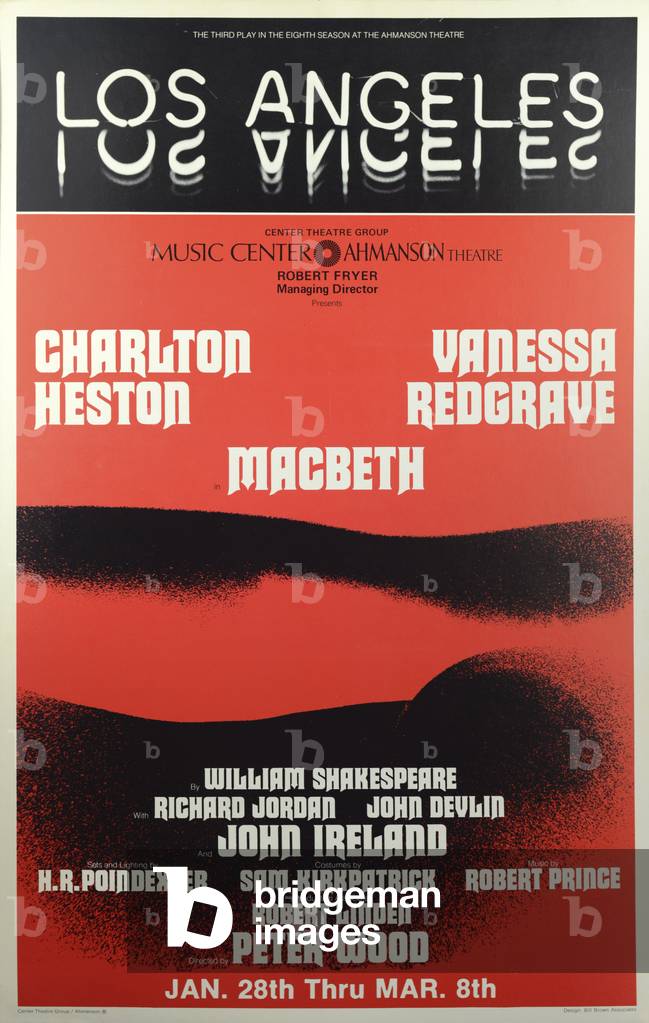

Heston’s break came with the emergence of live television, dominated by a group of directors, and writers, plus a horde of actors who found experience and employment in modern and classic plays. Heston played Antony again, for television, and soon after for Bradley in the film shot in Chicago. He also played Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, Macbeth in a 90-minute version, and Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew. The pay was low and the work hard, but by 1950 he was an experienced actor whose destiny was Hollywood.

His debut was the thriller Dark City and during the next two years he played in The Savage and a heated melodrama Ruby Gentry (1952), as Jennifer Jones’s lover. But it was the oft-quoted sighting by Cecil B DeMille that secured the role as circus manager in The Greatest Show on Earth. The film proved a smash hit and led to 10 films in three years.

He played Andrew Jackson in The President’s Lady, Buffalo Bill Cody in Pony Express, and in The Naked Jungle he fought against an advancing tide of ravenous ants. Gentler times came in a rare comedy, The Private War of Major Benson (1955).

A return to DeMille the following year ushered in the most prolific and successful period of his screen career, when he counted high among Hollywood’s top leading men. The Ten Commandments (1956), in which he played Moses, set the seal on his work and gave him the ability to choose his roles, generally with care and acumen. Sometimes intriguingly, as in the case of Orson Welles’s quirky, magnificent Touch of Evil (1958), where Heston, against type, played the Mexican detective Vargas. It was arguably his only work for a great director and he acquitted himself well.

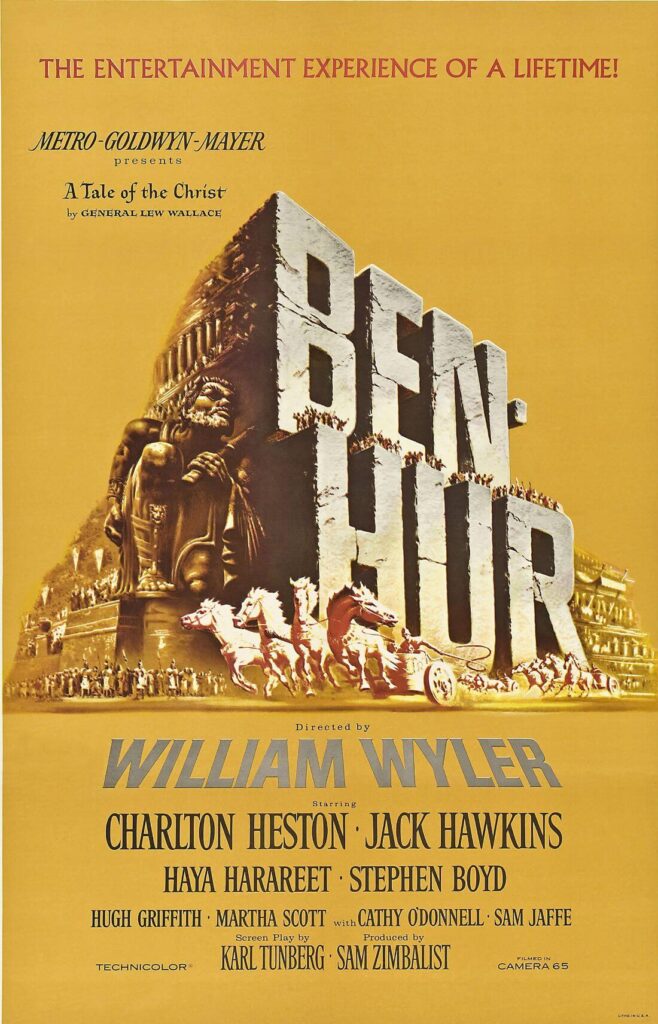

In the same busy year he went straight into a prestige Western opposite Gregory Peck, The Big Country. Its director, William Wyler, then gave him his most important break – the title role in Ben-Hur (1959). A vast, exhausting part, it won Heston the Oscar as best actor and set him in a class apart. The physique (Heston had been a youthful footballer and played tennis very competitively throughout his life) and the broken-nosed, granite face became associated ever afterwards with historical characters.

Two years later he compounded this by appearing in an exhilarating El Cid, playing the title role of the legendary 11th-century Spanish warrior.

Time out for some lighter films, then a brilliant flawed western as Major Dundee (1965), directed by the capricious Sam Peckinpah, whose directorial manner did not sit happily with the orthodox dedication of his star. Even so, Heston sacrificed his considerable salary to help complete the film and later supported Peckinpah against studio interference and re-editing. His performances as Ben-Hur, El Cid and Dundee represented the pinnacle of his career.

More gruelling work followed: playing John the Baptist in the dreary The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), then Michelangelo in The Agony and the Ecstasy, depicting the sculptor’s labours painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. He was out-acted by Rex Harrison, playing the Pope, in that particular movie but then received much better reviews than his idol Laurence Olivier when they co-starred in Khartoum (1966).

He returned to the west in a sombre character role, playing the lead as Will Penny (1968), a film which he and the critics regarded more highly than the public. He fared better commercially in the first and best of the series, Planet of the Apes (1968), directed by a friend and collaborator from their television days, Franklin Schaffner. They also made the intriguing historical drama The War Lord (1965). The public proved dismissive of his subsequent work, Number One (1969) – a football story which surfaced in Britain only at the National Film Theatre. In between there had been a television movie in which he played God.

He was easily tempted back as Antony in a further version of Julius Caesar (1970). It proved stagey and dull, although Heston held his own opposite John Gielgud, and easily outshone Jason Robards as a lamentable Brutus. He sought and found some commercial success with the lengthy The Hawaiians (1970) and a futuristic thriller, The Omega Man (1971). But times were changing: Heston was nudging 50 and a decade of rather different films loomed.

He found himself battling against manmade catastrophes and in situations where strength and an overwhelming desire to survive became paramount. He could be seen as the Captain in Skyjacked (1972), as a heroic LA engineer in Earthquake, as the passengers’ saviour in Airport (both 1974). And again as captain in Two-Minute Warning and The Battle of Midway (both 1976).

Between times he enjoyed great success as a police detective in the sombre Soylent Green (1972), trying to stave off the end of the world, and tellingly played Cardinal Richelieu in both Musketeers’ films, energetically directed by Richard Lester. Sadly, none of Lester’s invention rubbed off on Heston when he turned director with Antony and Cleopatra (1973). Instead his directorial influences were Schaffner and Wyler. Having adapted the play for the screen, cast it, played Antony and directed it, the film became a labour of great love. Its failure upset him more than anything else in his long career.

After a flurry of so-so movies, he starred as a fur trapper in a film written by his son Fraser, The Mountain Men (1980), and in the same year compounded that error with the ludicrous The Awakening. With flagrant lack of taste but admirable family loyalty, he directed Mother Lode (1982), from another script by his son, who also produced the movie. Its lack of success ushered in a major career change with a move towards television and stage work. His persona seemed at odds with the lighter style of acting current in the 1980s.

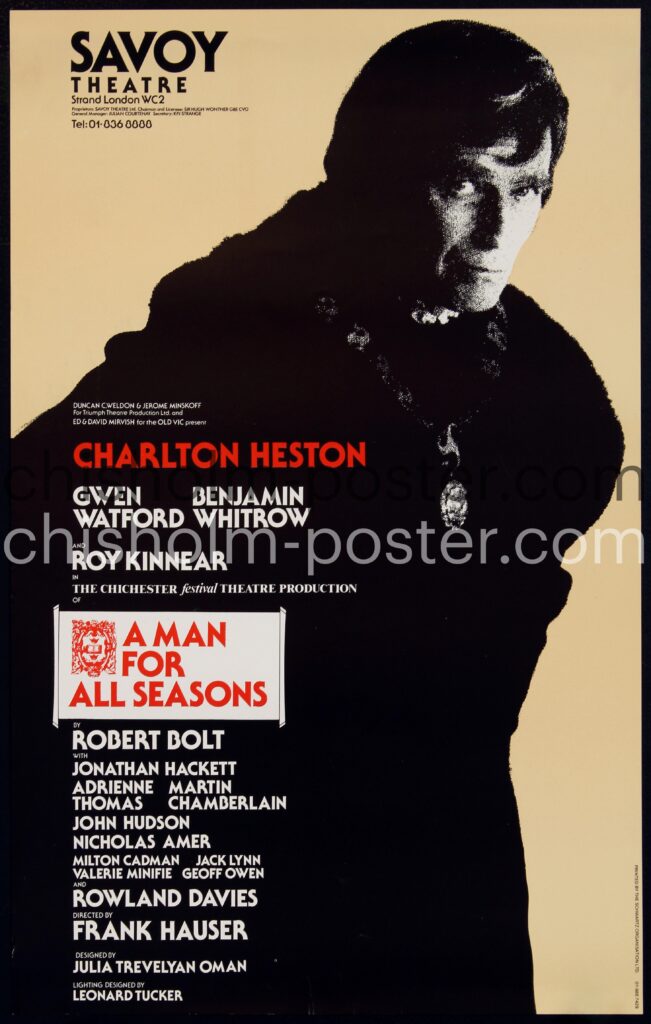

Among the television parts he took on was a two-year stint as Jason Colby in The Colbys (1985-87). One of his favourite stage roles – played several times, including a successful London run – was as Sir Thomas More in Robert Bolt’s A Man For All Seasons. Working with his son he filmed it, using his experience and some stage cast members, turning it into a television success. This quick and profitable film led Ted Turner to finance him again in a retelling of Treasure Island with Heston as Long John Silver.

Also in 1990, Heston played in yet another remake – as the Scottish grandfather in The Little Kidnappers. The same year, among other projects, he played God in a sentimental film, Almost an Angel. He continued working with Fraser, filming a play he had directed and acted in, as an untypical Sherlock Holmes. Crucifer of Blood (1991) proved a rather stolid work and was quickly followed by a TV film where his role as the Captain and its title – Crash Landing, the Rescue of Flight 232 – tells all.

He guested as Good Actor in the juvenile Wayne’s World 2 – and also in 1993 took a small role in the enjoyable western Tombstone. He was called in by director James Cameron for a key role in the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle, True Lies, as the only actor around who looked as though he could intimidate Arnie on screen. His flinty demeanour did the trick and Heston enjoyed the challenge. He then headed for his favourite city, London, to act the Player King in Kenneth Branagh’s interminable Hamlet (1996) and was called on for his imposing voice to narrate Disney’s animated feature Hercules.

A couple of years before, he had published his autobiography, In the Arena. Its 600 pages covered a busy, fulfilled life that placed family and friends above career. It was his third publication. He had earlier edited a version of his meticulously kept journals detailing his work, and in 1990 his fascinating Beijing Diary recorded his commitment to a project in China where – for no pay – he had directed The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, a play he had acted in several times.

In June 1998, Heston was elected president of the National Rifle Association, for which he had posed for ads holding a rifle. He delivered a jab at then President Bill Clinton, saying: “America doesn’t trust you with our 21-year-old daughters, and we sure, Lord, don’t trust you with our guns.” He stepped down as NRA president in April 2003, the year he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Film-maker Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine (2002) tried to show him as callous towards shooting victims. But Moore’s treatment of the visibly frail actor may have backfired. Heston made no apology for his rightist views, and his belief in the individual and nonconformity was reflected in many of his preferred stage characters, from Holmes to Thomas More and Becket, James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey into Night and, of course, Antony. In the theatre he worked often with Lydia, from an early success in The Detective up to Pete Gurney’s Love Letters.

A French critic once described Heston as the axiom of cinema, but the reviewer who noted that if he had not existed then Hollywood would have needed to invent him probably got near the truth. “There was an epic, Everest-like quality to the man and many of the characters he played. He may not have counted as one of the wonders of the world, but he was surely an imposing part of its landscape.”

He is survived by his wife and children.

· Charlton Heston (Charles Carter), actor, born October 4 1923; died April 5 2008

from “The Guardia “ by Brian Baxter.