Nancy Davis obituary in “The Guardian”.

Nancy Reagan, who has died aged 94, had an extraordinary capacity to sit visibly entranced through the hundreds of speeches made by her husband, the 40th US president (and former actor) Ronald Reagan. But this public display was far different from the admiring conjugality of earlier first ladies such as Mamie Eisenhower and Pat Nixon. Behind Nancy’s gaze lay the reality of Ronald’s long political career – that it would probably never have happened without her influence.

She was born Anne Frances Robbins in New York. After her parents divorced and her mother, Edith, an actor, remarried, Nancy took her stepfather’s surname. Nancy Davis was a middle-ranking film actor in her 20s when she received her initial introduction to Reagan, having already told a friend that he was top of her list of Hollywood’s eligible bachelors.

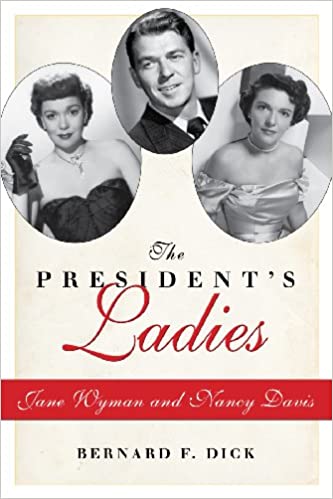

It was at the height of the McCarthyite purges, and Reagan was head of the Screen Actors’ Guild. The ostensible reason for the meeting was that Nancy had been confused with a leftwing actor of the same name and was afraid of being blacklisted for her supposed communist leanings. The chemistry between the two emerged at this first encounter, but Reagan, still bruised by his divorce in 1949 from the actor Jane Wyman, did not propose for a further two years. When the couple married in 1952, the film industry was in turmoil and both their careers were under threat.

A US supreme court decision had severely constrained the major studios’ business practices, and cinema audiences had slumped by half with the rise of television. By 1955, however, Ronald had secured a lucrative television contract with General Electric and, as the family finances improved, Nancy embarked on a campaign of relentless networking. Central to it was an influential magazine publisher, Walter Annenberg, whom she had met through her film connections.

Annenberg was a major Republican party contributor whose generosity was eventually rewarded by appointment as President Richard Nixon’s ambassador in London. Through his contacts, Nancy had, within a few years, worked her way into an influential private charity known as the Colleagues, with membership limited to 50 of the most socially prominent wives in Los Angeles. That, in turn, brought her in touch with an influential band of Republican businessmen.

They bankrolled Ronald’s political ascent and remained important as his unofficial “kitchen cabinet”. Holmes Tuttle was one of America’s most successful car dealers, Justin Dart owned a chain of pharmacies, Henry Salvatori was an oil prospector (alleged also to run various CIA front companies) and Alfred Bloomingdale was the owner of a chain of department stores.

The critical moment arrived for Nancy in 1962, when General Electric abruptly ended Ronald’s contract because he refused to tone down the political content of the speeches he was making on company tours. By then, however, he was much in demand by business and rightwing political groups, who offered thousands of dollars to hear him espouse an increasingly conservative philosophy.

Nancy’s own political views had been shaped by her stepfather, Loyal Davis, described even by his Republican friends as a bigot, given to antisemitic and racist outbursts. Though Nancy did not go that far, she was certainly well to the right of her husband and undoubtedly achieved a significant shift in his stance. During his union days in Hollywood, Ronald had been a Roosevelt Democrat. After their marriage, he moved steadily to the right and, when the ultra-right Senator Barry Goldwater announced his 1964 presidential bid, Ronald became one of his most fervent campaigners. Once Goldwater’s campaign had ended in one of the worst Republican defeats in history, Tuttle decided that he and his friends must rebuild the party, starting in California. Deeply impressed with Ronald’s performance and popularity, they urged him to run against the state’s Democratic governor, Pat Brown, whose vigorous eight years in office were by then running out of steam. This was when Nancy came into her own.

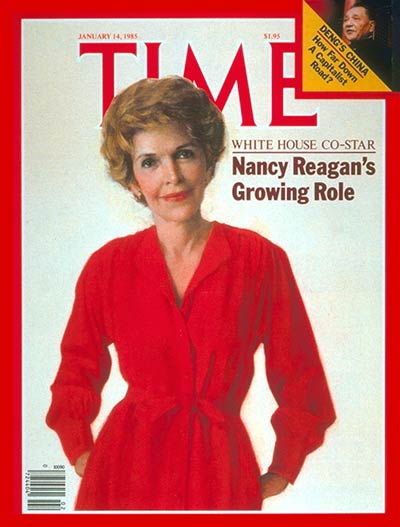

She masterminded much of her husband’s campaign, including a fund-raising drive sponsored by celebrities such as Walt Disney, James Cagney, Robert Taylor and Randolph Scott. She was never off the telephone to rich potential backers and became notorious for her gimlet-eyed vetting of campaign staff. Ronald romped into the governorship in 1967 by a margin of nearly two to one. His wife’s obvious influence on political issues soon sparked controversy – and the start of Nancy’s repeated feuds with the media.

Refusing to occupy the (admittedly tatty) governor’s mansion, she persuaded the kitchen cabinet to buy and furnish a grander alternative, and then arranged for their costs to be made tax-deductible. She also continued her tight control of staff to the extent that Michael Deaver, later one of Ronald’s key White House aides, was covertly assigned to a “mommy watch” which served to protect staff from her vengeful descent (a role at which he became so adept that it endured through the White House years).

When Ronald’s governorship ended, in 1975, and he clawed his way up the party ladder, Nancy’s political influence was well entrenched and growing. As Lou Cannon commented in his biography of the president: “They made a good political team. He was a dreamer, preoccupied with ultimate destinations. She was a practical person who worried about what lay around the next bend.”

She had more and more to worry about, starting with an attempted assassination by John Hinckley Jr just after Ronald became president in 1981. During her Hollywood days, she had dabbled in astrology. After the shooting she became almost manic about its influence and seriously disrupted a number of international and other political gatherings with arbitrary changes in the president’s schedule, made after she had consulted the astrologer Joan Quigley.

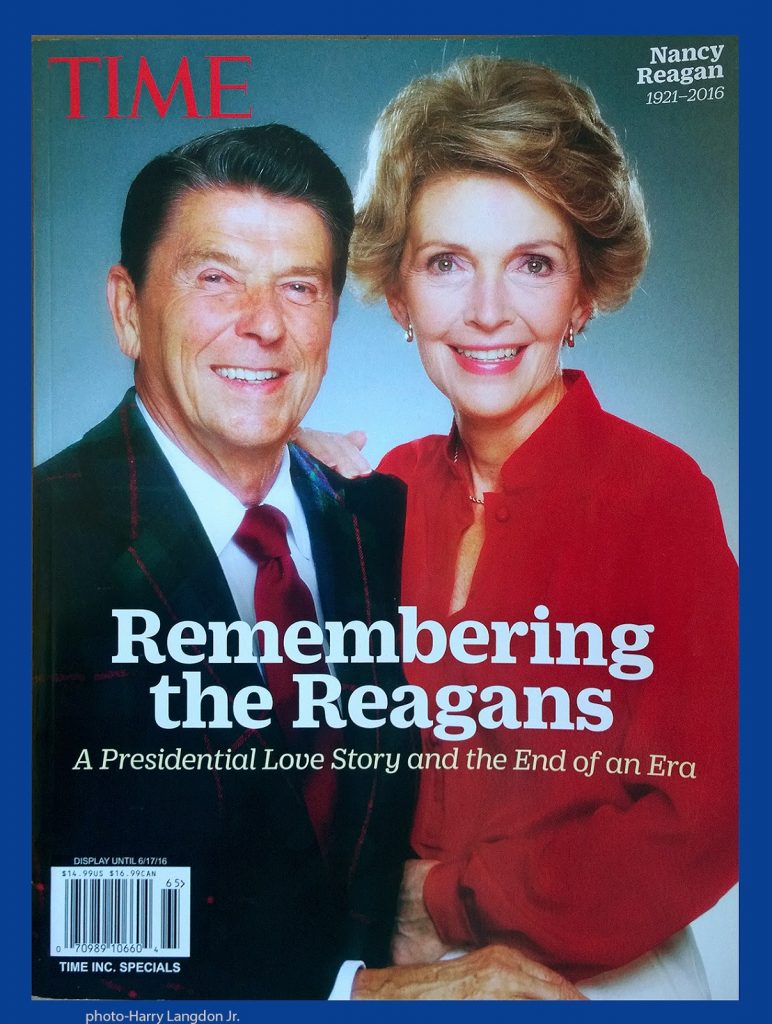

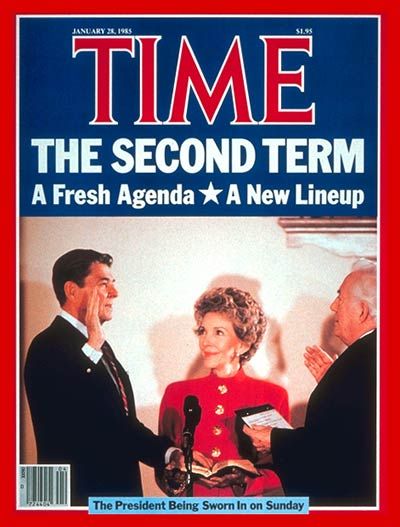

In part this may have been a reaction to the psychological impact of Ronald’s wounds, which was much greater than admitted at the time. He, too, was deeply superstitious and relied heavily on omens and instinct. By the end of his first term, Nancy was worried enough about his condition to try to stop him from seeking re-election. She failed, but spent more and more time dealing with the growing signs of the mental decline that eventually overtook him.

Its principal public impact came during the Iran-Contra scandal, when a low-level White House aide clandestinely organised illegal arms sales to Tehran in the hope of getting American hostages released and then diverted the money to equally illegal funding of rightwing rebels in Nicaragua. As details of the affair emerged, they brought clear evidence that the president had no idea what he might have authorised or what his staff had told him.

Nancy realised far earlier than most that he was in serious danger of impeachment. She set aside her partisan prejudices to call in the veteran Washington lawyer (and one-time Democratic party chairman) Robert Strauss in the hope that he could convince Ronald that he was in serious trouble. The president would not accept any responsibility and eventually got away with a televised apology for the scandal.

Ronald, by then 76 years old and showing it, was about the only American who did not think he was culpable. The official inquiry dodged the issue and put much of the blame on his chief of staff. In 1989, when Ronald left office, Nancy took him back to California, where his increasingly rare public appearances revealed growing evidence of his decline.

In 1994 the couple acknowledged that he had Alzheimer’s disease and their final 10 years until his death in 2004 passed with him losing every memory of his career, and eventually unable to recognise even Nancy.

She is survived by their daughter, Patti, and son, Ron.

Ronald Bergan writes: By far the best role Nancy Reagan ever had was as US first lady. However, as Nancy Davis, her acting career was by no means ignominious. She appeared in several reasonably good movies and TV shows. Unfortunately, the only leading parts she was given by MGM, who had signed her to a five-year contract in 1948, were in the studio’s B features, mostly as devoted housewives.

Having taken a degree in drama at Smith College in Massachusetts, Davis managed to get a role in a touring company production of the play Ramshackle Inn, starring ZaSu Pitts, a friend of her family. After the two-month run ended in New York in December 1944, she decided to stay on in order to fulfil her theatrical ambitions. It took a year of failed auditions, and some modelling work, before she landed the role of a Chinese lady-in-waiting to Mary Martin in the Broadway musical Lute Song.

Her screen debut came in William Dieterle’s romantic fantasy Portrait of Jennie (1948), where she is seen at the end of the movie, with Nancy Olson and Anne Francis, standing in awe in front of the eponymous painting. The following year, she played the wife of an ambitious paediatrician in The Doctor and The Girl; and Barbara Stanwyck’s confidante in East Side, West Side.

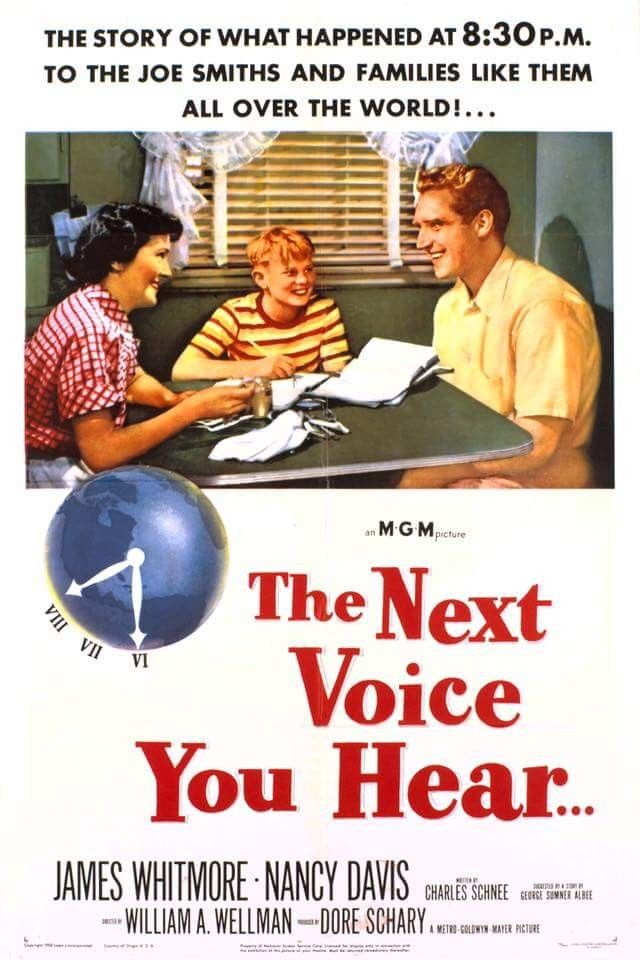

Shadow on the Wall (1950) gave Davis her first substantial part, as a cool-headed child psychiatrist, trying to get the truth of a murder witnessed by a young girl. The title of William Wellman’s The Next Voice You Hear … (1950) refers to a mysterious voice on the radio claiming to be God that Davis as the pregnant Mary Smith and her blue-collar worker husband Joe (James Whitmore) hear every night. The film was a comforting exploration of faith, in which Davis, according to the New York Times, “was delightful as the gentle, plain and understanding wife”.

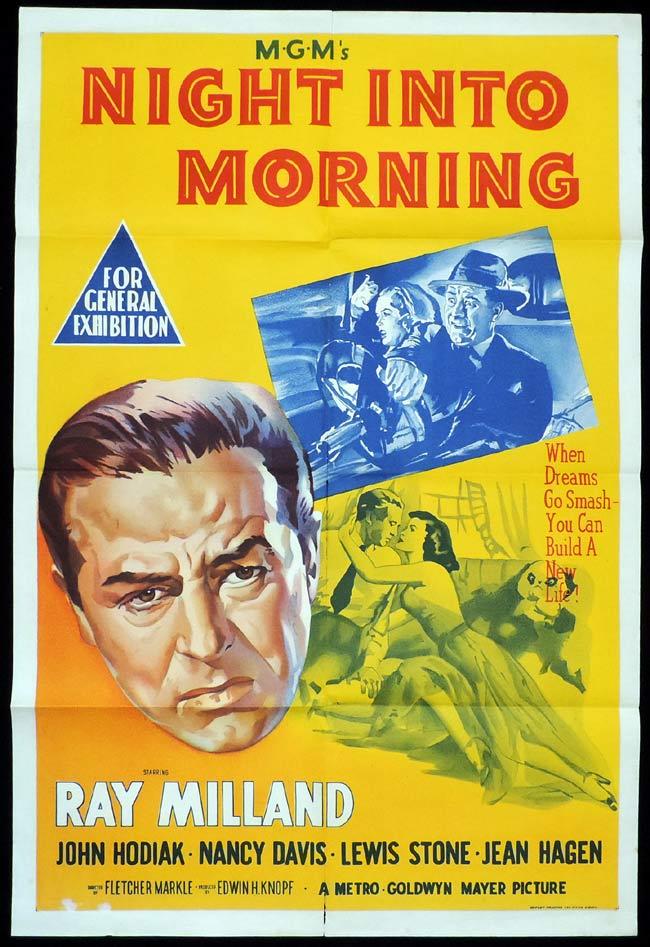

In Night into Morning (1951), she is once more in a sympathetic role as a widowed teacher who helps to console her colleague Ray Milland after his wife and child are killed in an accident. In the episodic It’s a Big Country (1951), Davis is seen again as a teacher, who recommends that one of her pupils needs spectacles, against the wishes of the boy’s stubborn macho father.

Talk About a Stranger (1952), an effective liberal parable, saw Davis reprising the role of a pregnant mother, this time of a boy whose dog has been poisoned, and who blames a foreigner. Her husband was played by George Murphy, who became a Republican senator, and to whom Ronald Reaganonce referred as “my John the Baptist”. Nancy then wound up her MGM contract in Shadow in the Sky (1952) as (what else?) a loving housewife and mother who has to cope with the shell-shocked best friend (Ralph Meeker) of her husband (Whitmore again).

Though by now she had married Ronald Reagan, she continued to act, mainly concentrating on television, and appearing with her husband in episodes of the Ford Television Theatre and General Electric Theater series. In addition, she made three further movies. In Donovan’s Brain (1953), she was the lab assistant and loyal wife of a scientist (Lew Ayres) who has managed to keep a dead man’s brain alive. When she questions his experiments on a monkey, and he explains the reasons why, she replies: “You’re right, darling, I’m being silly.” “Thanks, dear,” he says. “Now will you go and make us one of those wonderful stews.”

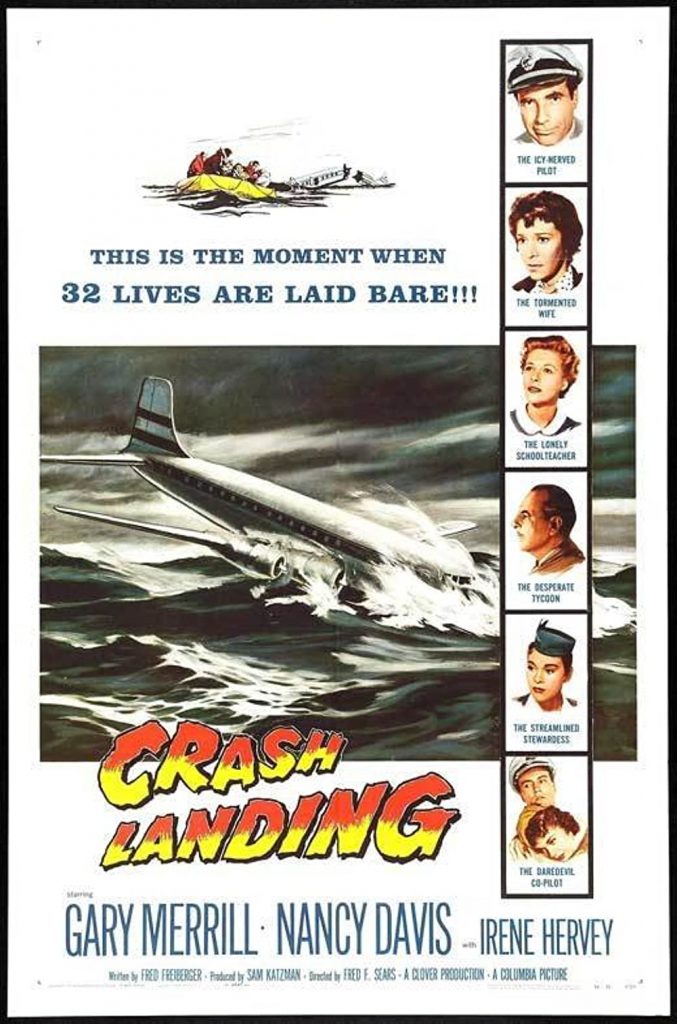

The only feature film the Reagans appeared in together was a minor war film, Hellcats of the Navy (1957), he as a submarine commander, she as a nurse. In her final movie, Crash Landing (1958), she is seen in flashback as the wife of a pilot in trouble (Gary Merrill), not really the sort of role to inspire her to continue in the acting profession.

• Nancy (Anne Frances) Reagan, actor and former US first lady, born 6 July 1921; died 6 March 2016