“Guardian” obituary from 2003

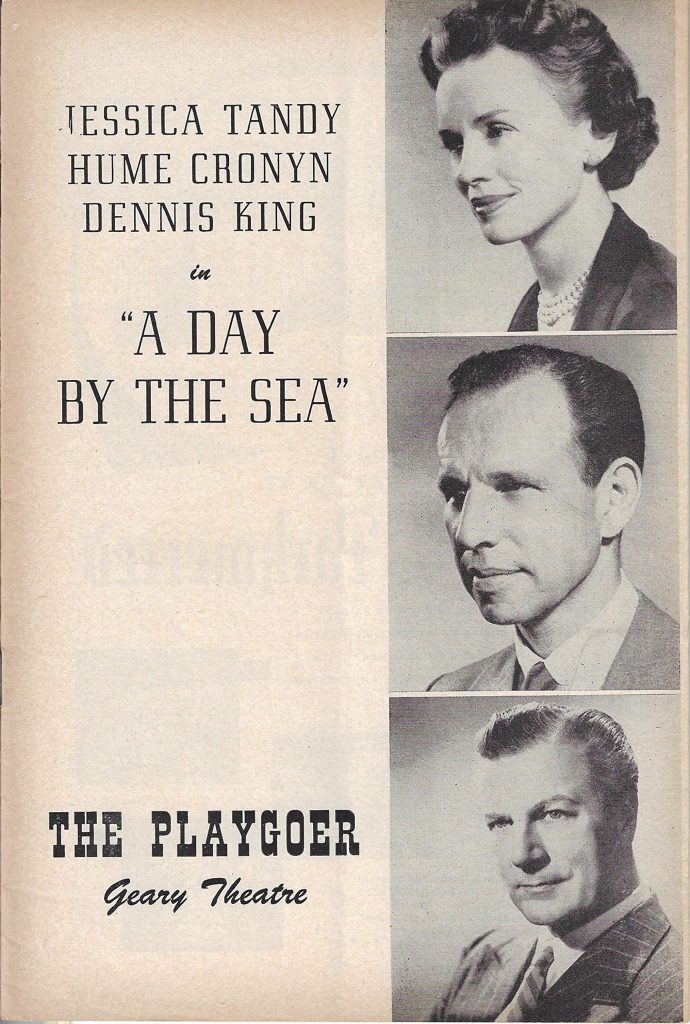

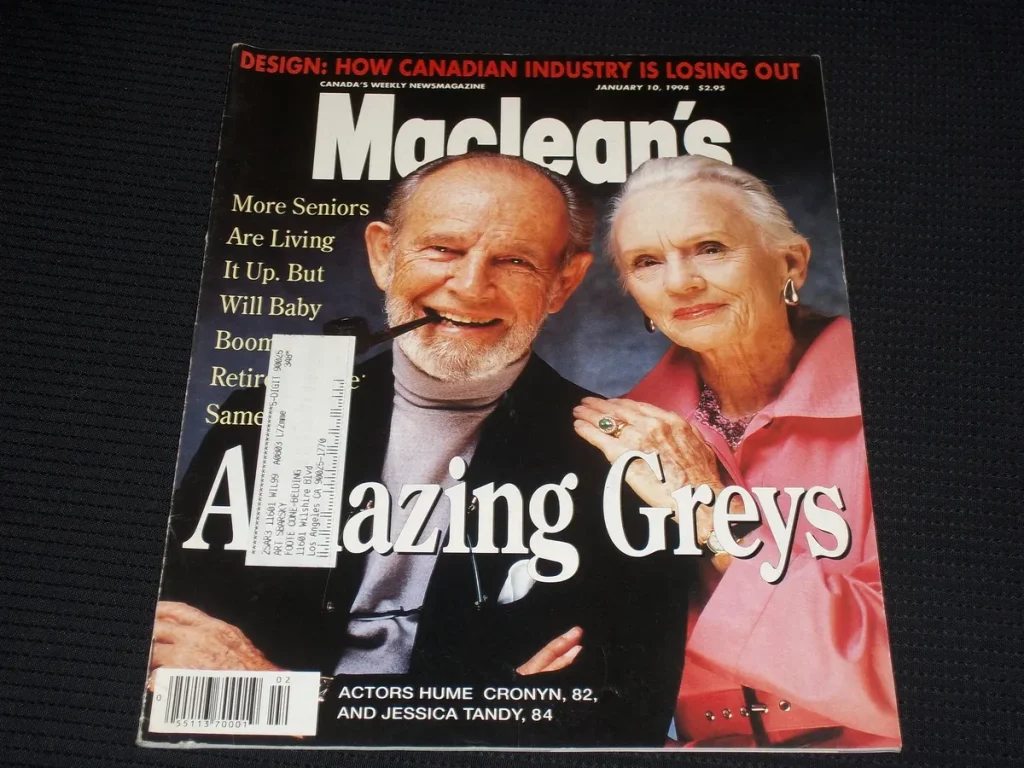

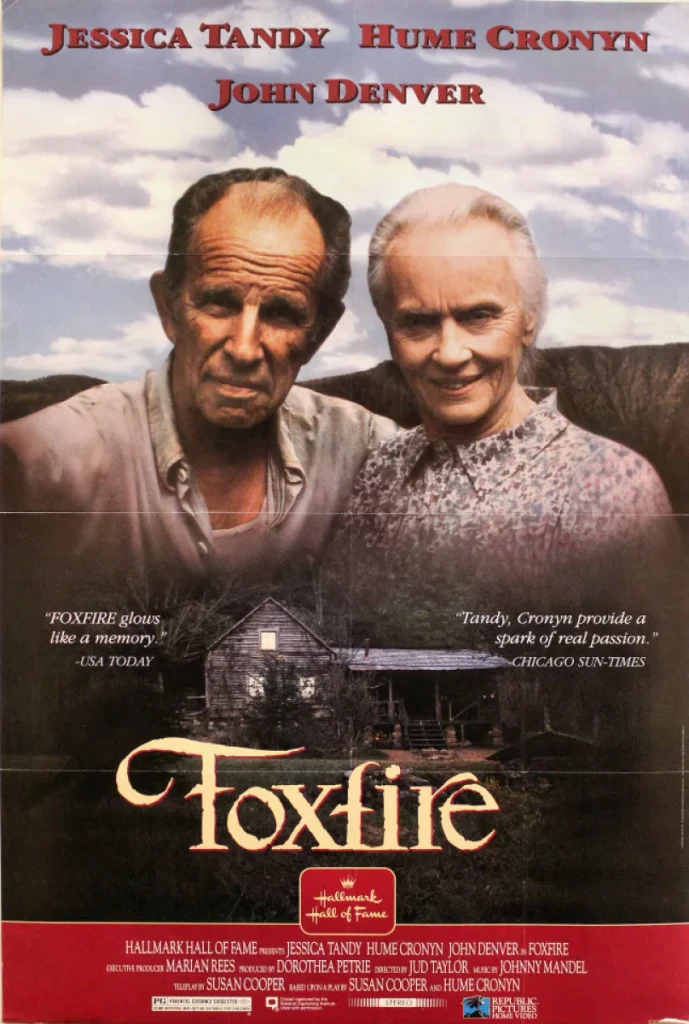

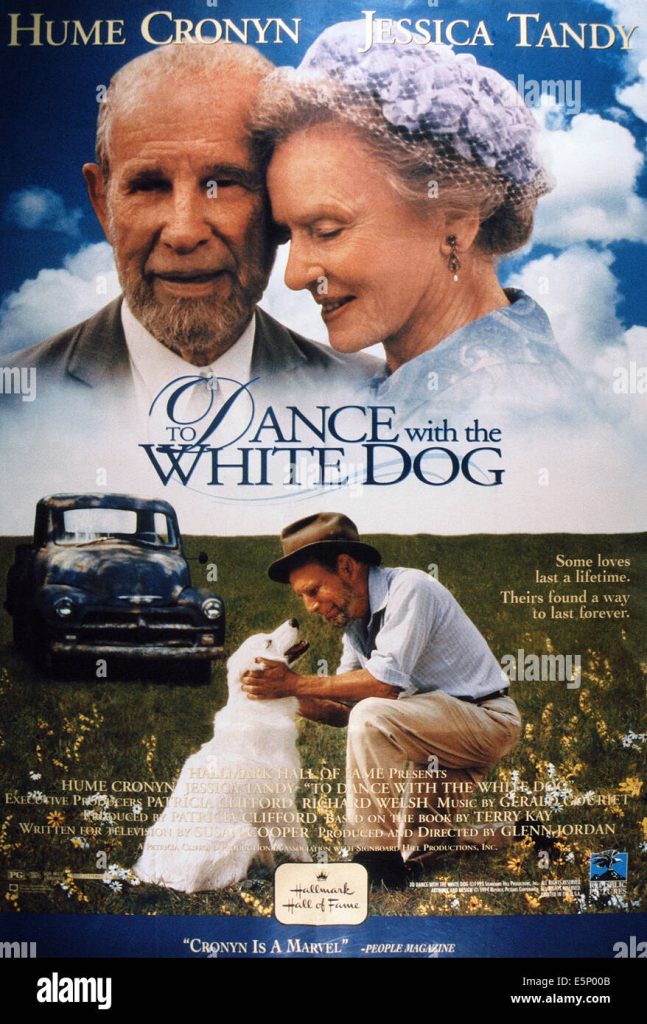

Unlike these two other pairings, they were an odd couple physically – she was angular and imposing; he was short and weedy. The English-born Tandy’s voice was clear and piercing; the Canadian Cronyn’s voice was nasal and querulous. But following their marriage in 1942 (two years after Tandy’s divorce from Jack Hawkins), they appeared in scores of plays and half a dozen films together. Each also had their own distinguished careers.

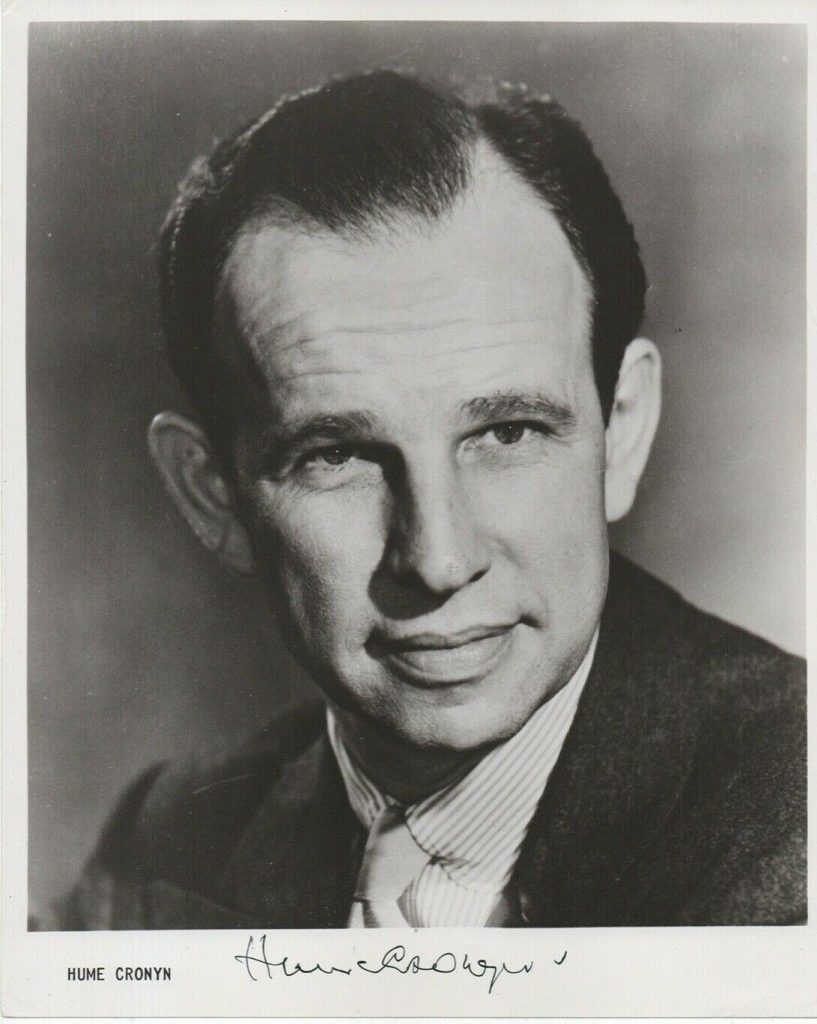

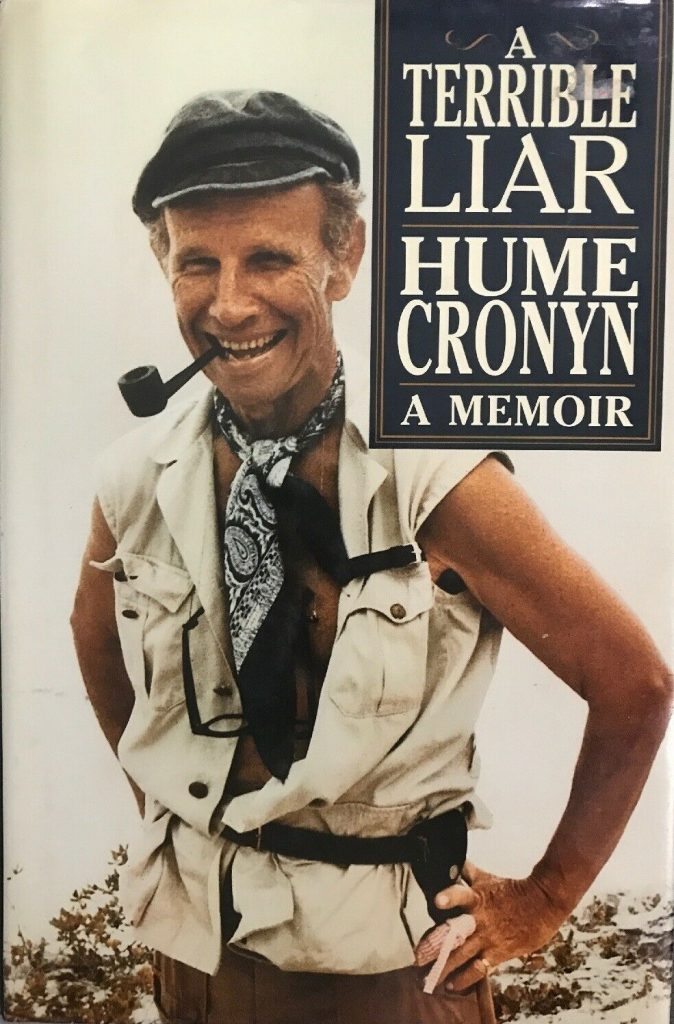

Cronyn was born in London, Ontario, into one of Canada’s most prominent families. His father, Hume Blake Cronyn, was a leading banker and politician, and his mother, Frances Labatt, was connected with the Labatt brewery. After a strict but privileged upbringing, he studied law at McGill University, Montreal, where he acted in student productions before going on to the American Academy of Dramatic Art. During the war, he produced, directed and appeared in revue for the Canadian active services canteen and toured US military camps.

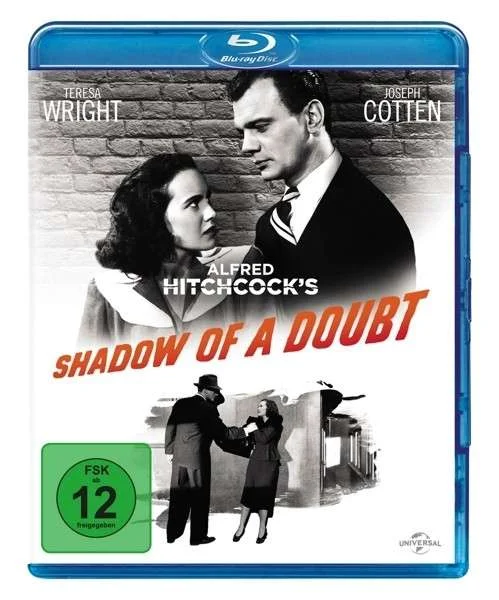

It was Alfred Hitchcock who gave Cronyn his first screen role in Shadow Of A Doubt (1943), playing Herbie Hawkins, an oddball neighbour obsessed with murder who does not know that the family next door is housing a real killer. The same year, in The Cross Of Lorraine, Cronyn played a French PoW discovered to be spying for the Germans; he is exposed by his fellow inmates and shot by the guards. It was the first of his many weasel parts, though an accident nearly prevented him from having any future career at all.

During the filming of Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944), in which Cronyn was the meek radio operator, he was dragged under the water of the studio tank and almost drowned while trapped beneath a boat. Happily, he was saved by a lifeguard whom Hitchcock had posted near the tank for just such an eventuality.

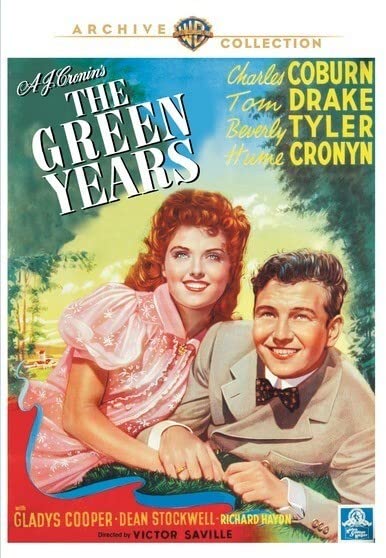

Cronyn was nominated for an Oscar for his role as the friend of concentration camp escapee Spencer Tracy in Fred Zinnemann’s The Seventh Cross (1944), in which Tandy – in her first film – played his wife. She then played his daughter (though she was two years older than him) in The Green Years (1946), based on AJ Cronin’s novel. Variety magazine claimed that he “wreaks every bit of tightfistedness and little-man meanness out of the role of head of the house that takes the small boy in”.

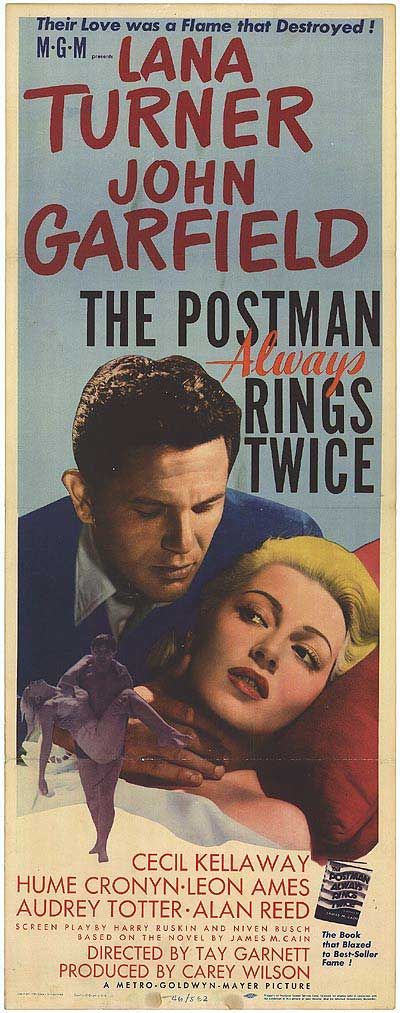

Better still was Cronyn’s performance in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), as the unctuous attorney who successfully defends the illicit lovers (Lana Turner and John Garfield) on a murder charge, a character closer to the spirit of the James Cain novel than anyone else in the film.

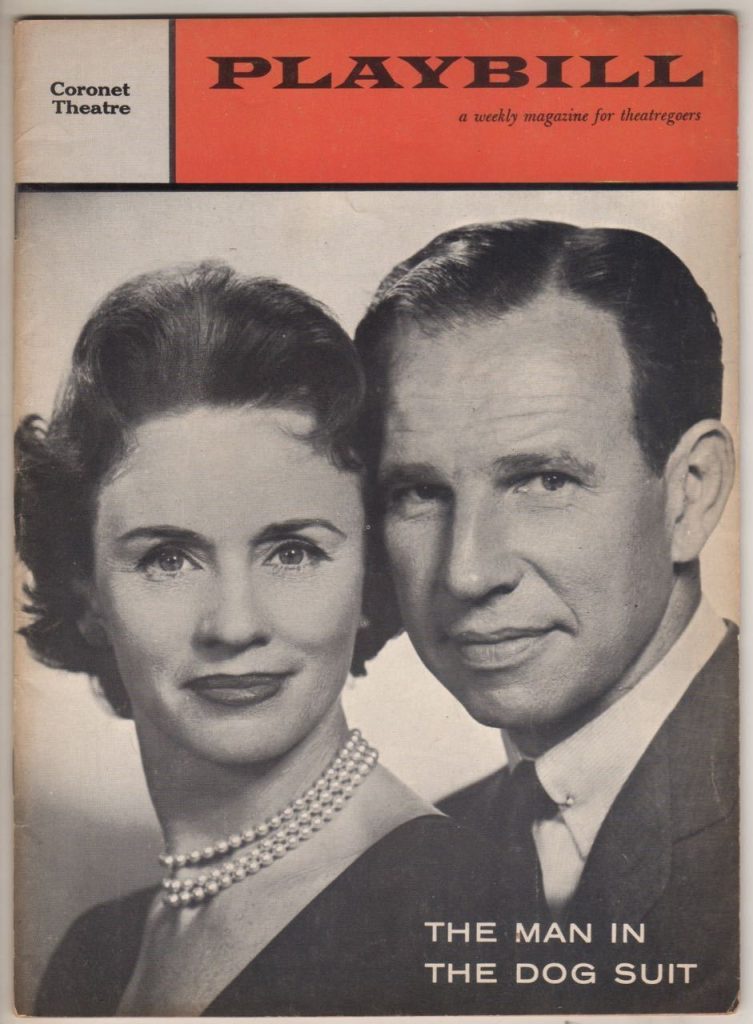

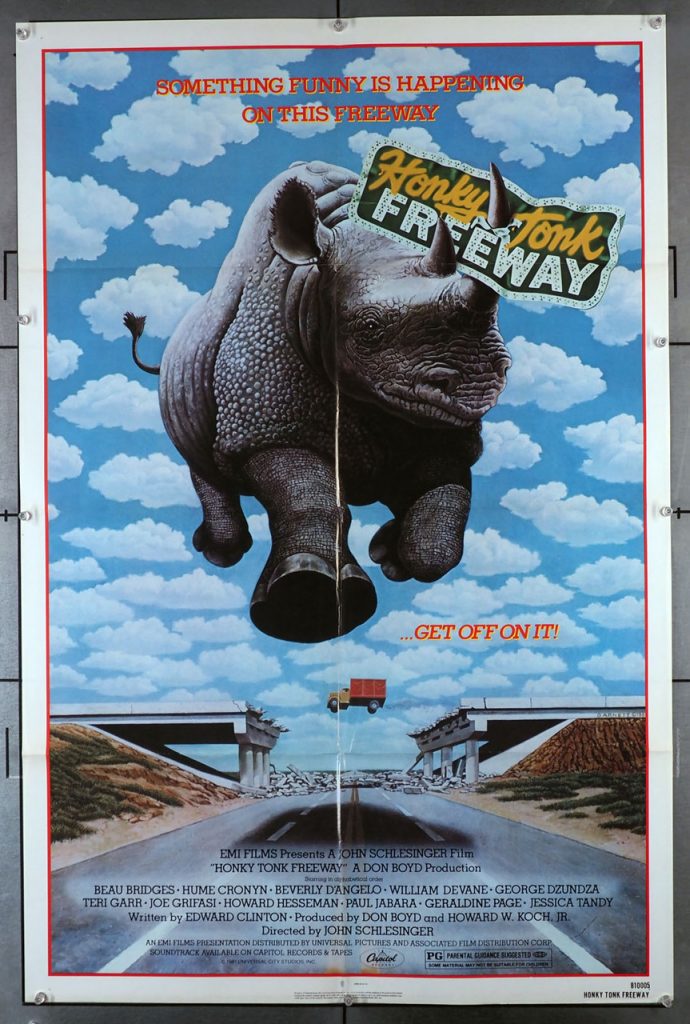

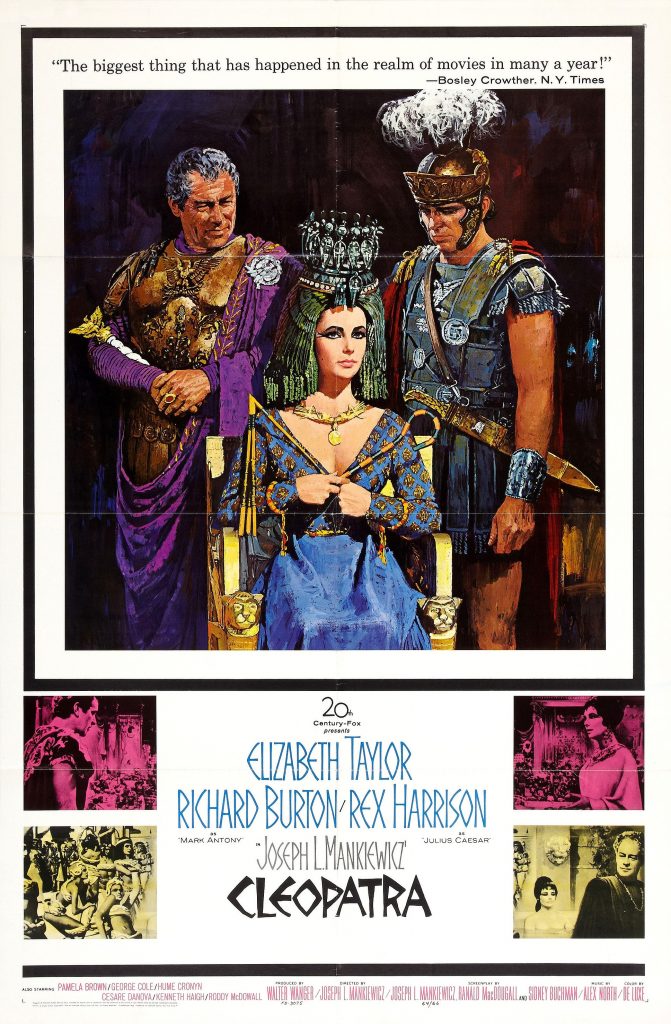

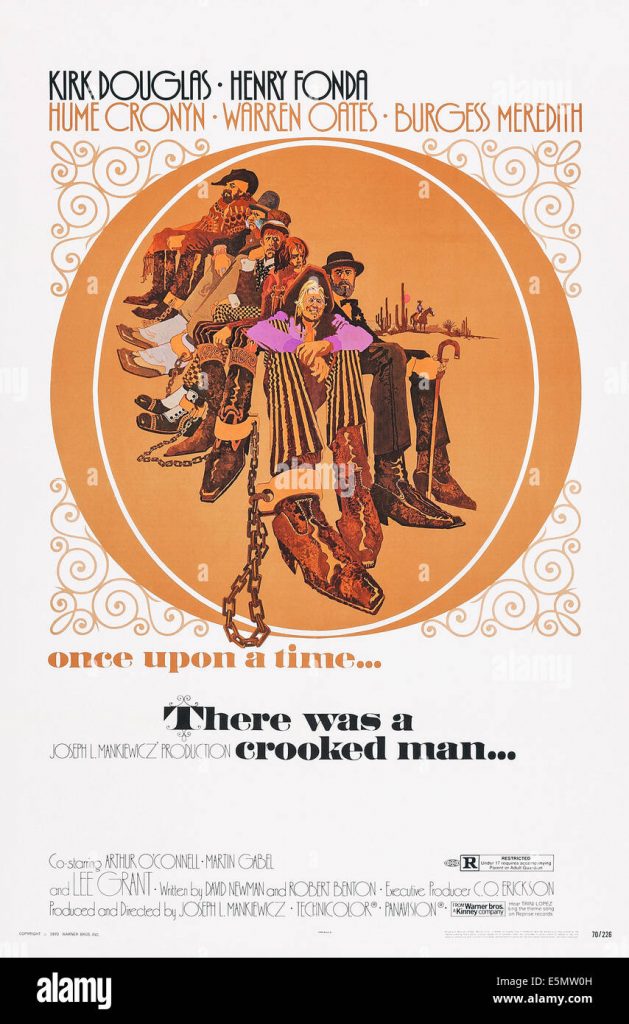

At the same time, Cronyn had been appearing spasmodically in films, notably playing Louis Howe, the asthmatic friend of President Franklin Roosevelt (Ralph Bellamy) in Sunrise At Campobello (1960), Deborah Kerr’s divorce lawyer in Elia Kazan’s The Arrangement (1969) and one of a homosexual couple in Mankewicz’s There Was A Crooked Man (1970).

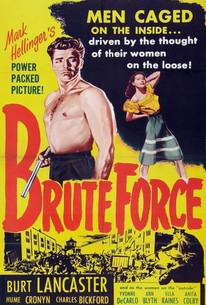

After convincingly playing the scientist Robert Oppenheimer in The Beginning Of The End (1947), a documentary-style story about the making of the first atomic bomb, Cronyn returned to “little-man meanness” in Jules Dassin’s powerful prison drama Brute Force (also 1947); second billed after Burt Lancaster, his sadistic warden is a chilling portrait of evil. Another odious character was his snivelling anatomy professor in Joseph Mankiewicz’s People Will Talk (1951), playing Cary Grant’s adversarial colleague who feels more at home dissecting corpses than talking to humans.

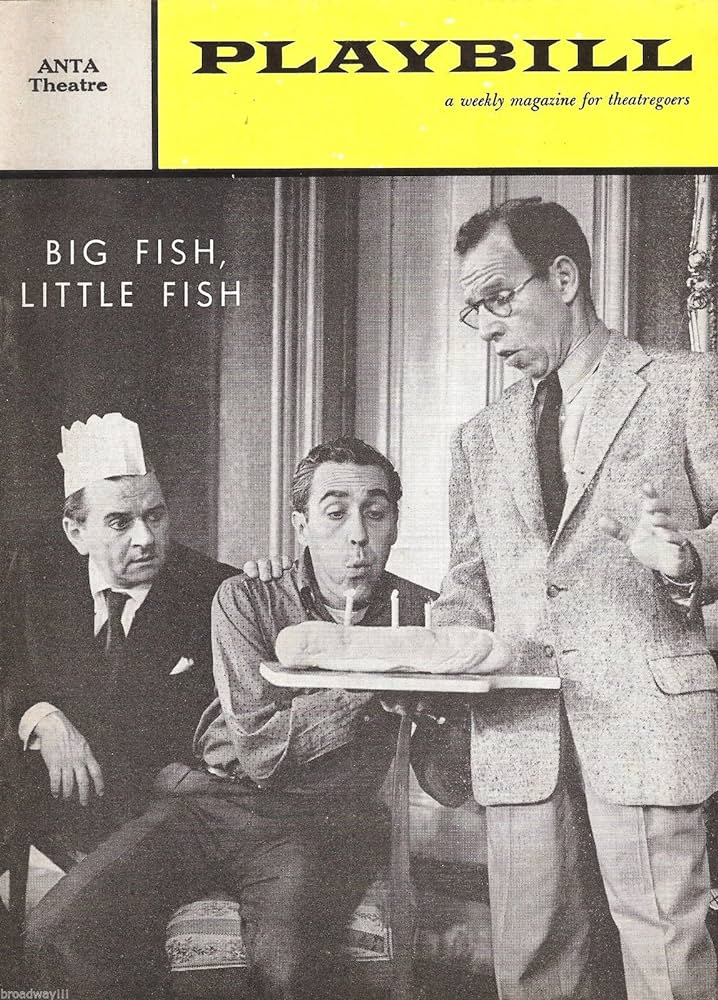

After this, Cronyn and Tandy decided to concentrate on theatre for the next two decades. Two of those years were taken up on Broadway in Jan de Hartog’s two-hander The Fourposter, which followed a couple from their wedding night to old age and death. The fact that the two stars were actually married gave their expert performances an extra poignancy.

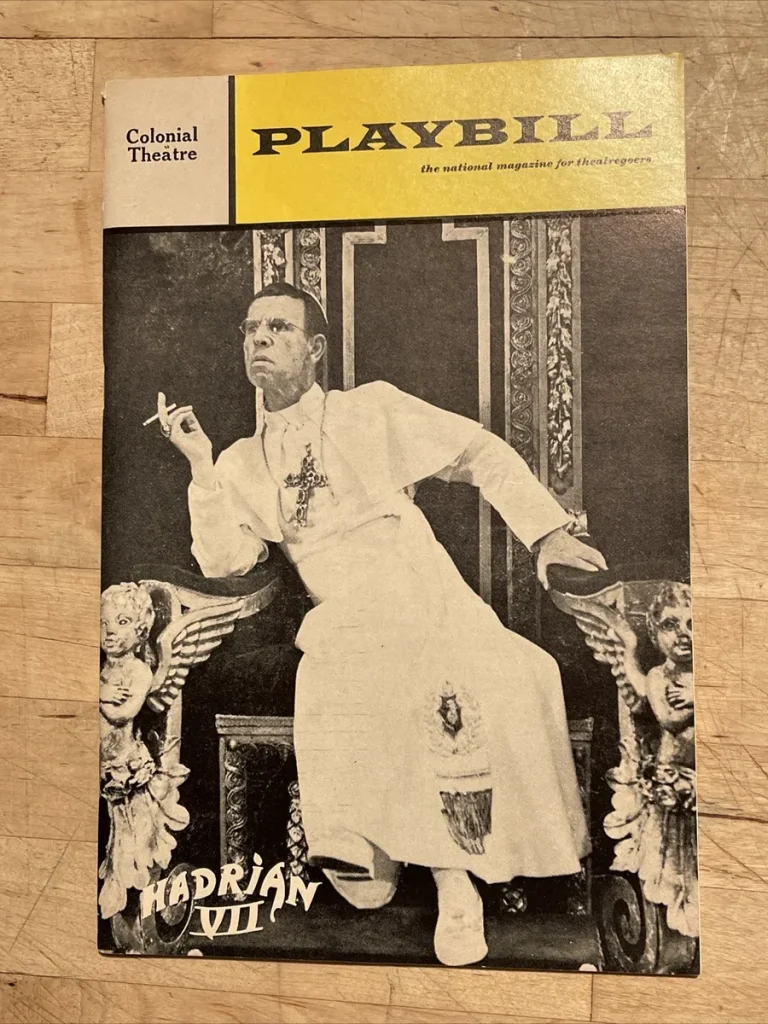

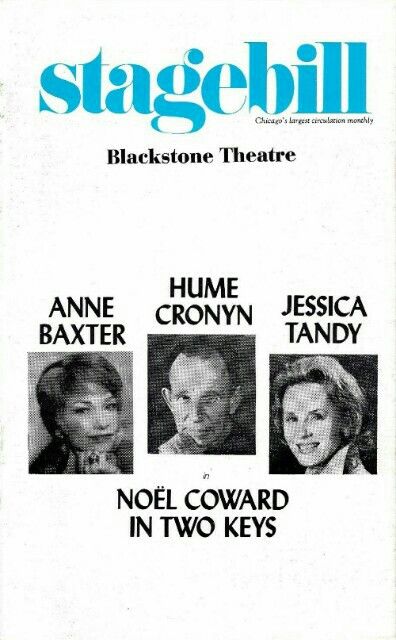

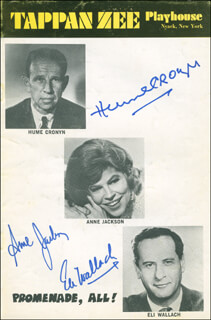

Subsequently, they alternated between Broadway, regional theatres, Stratford, Ontario, and the Tyrone Guthrie theatre in Minneapolis, where they appeared mostly in the classics, with Cronyn taking on Shylock, Bottom, Richard III, Harpagon in Molière’s The Miser, and Willie Loman (opposite Tandy) in Death Of A Salesman.

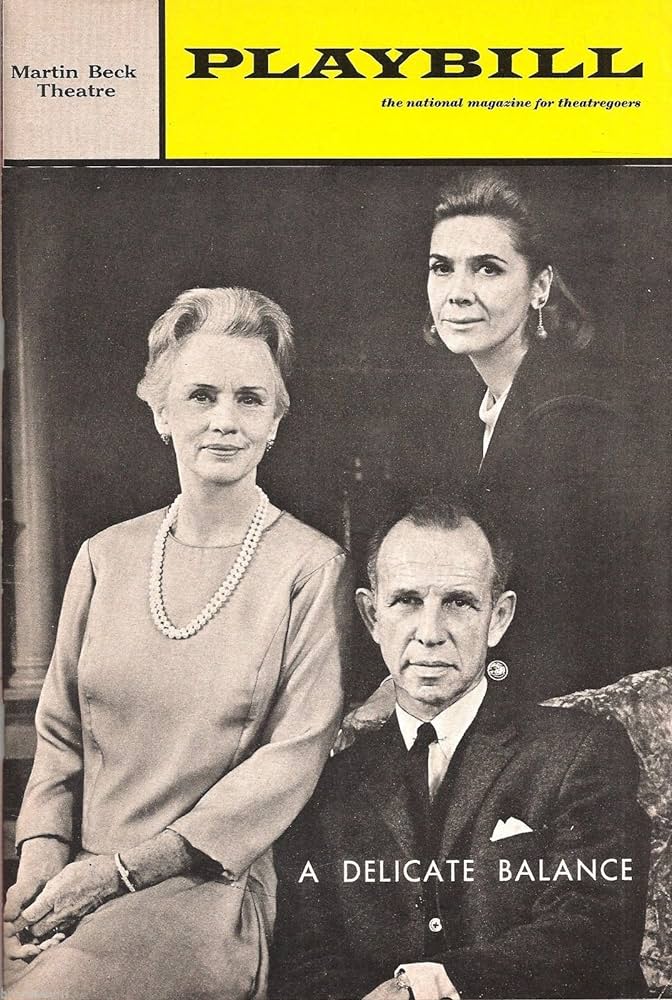

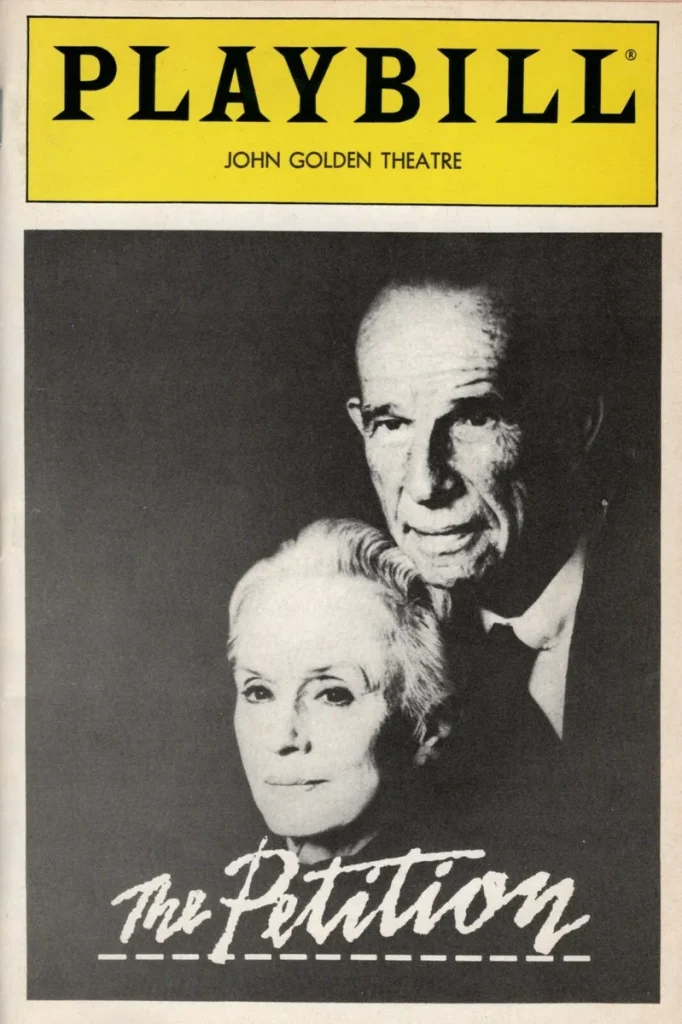

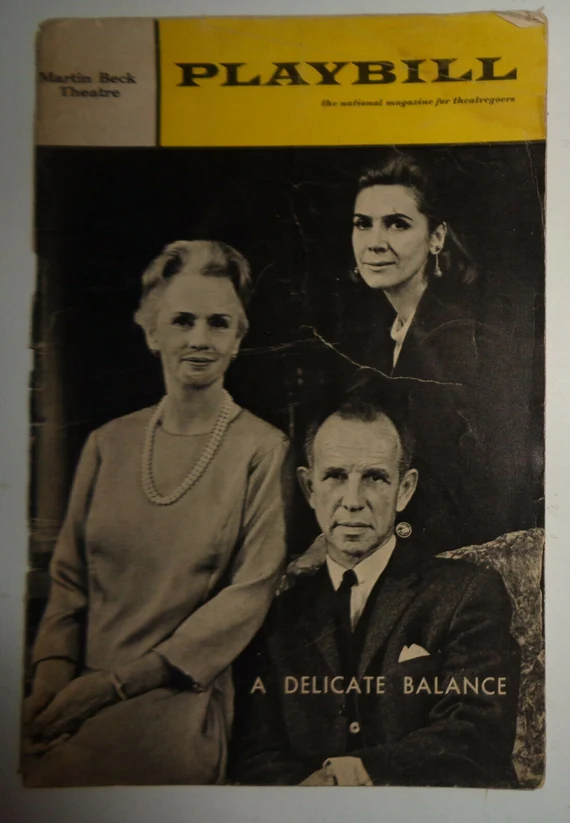

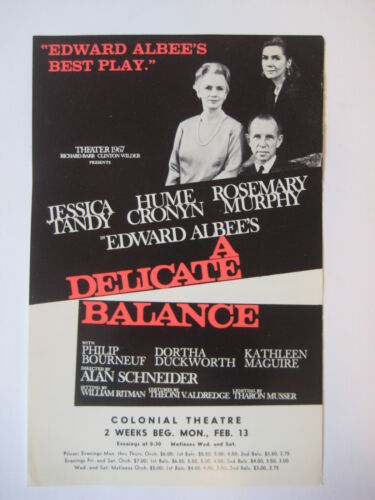

In 1964, Cronyn received a Tony and the New York drama critics’ award for his Polonius – a part he was born to play – in John Gielgud’s production of Hamlet, with Richard Burton in the title role. In the 1970s, he and Tandy, who were elected to the Theatre Hall of Fame in 1974, played a loveless couple in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, and inmates of an old people’s home in The Gin Game, in New York and London.

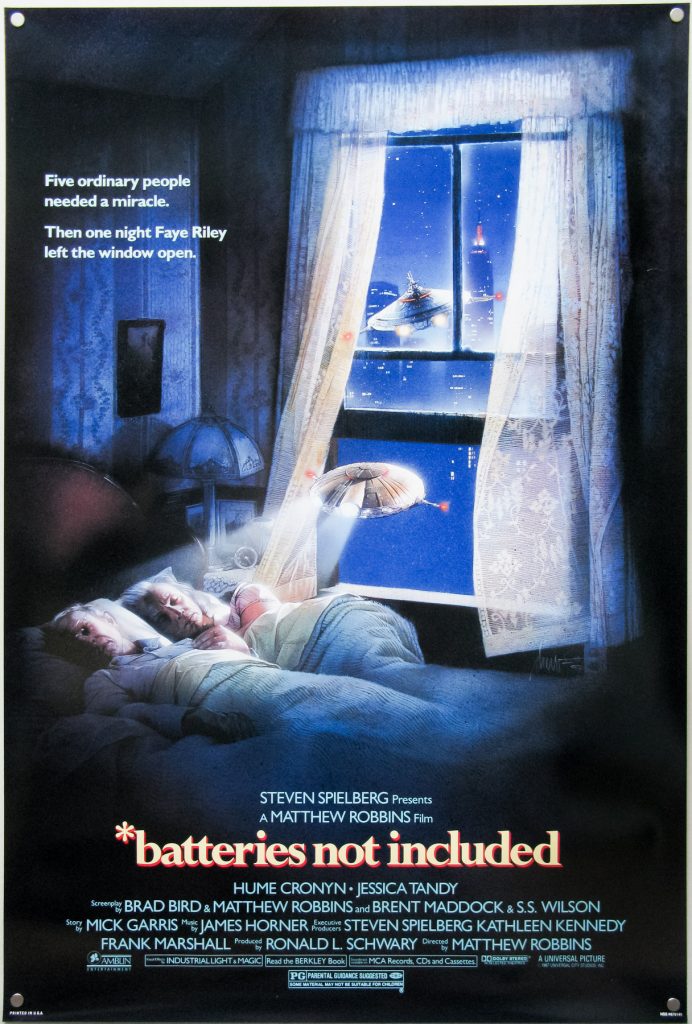

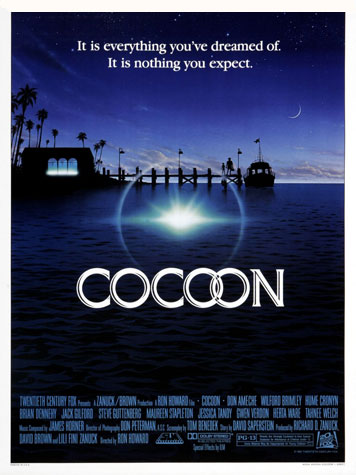

It was in the 1980s, however, that Cronyn and Tandy were discovered by a new generation of filmgoers when they appeared as an eccentric elderly couple in several movies, particularly Cocoon (1985) and its sequel, Batteries Not Included (1987), in which they fight a greedy estate agent with the help of aliens. After Tandy’s death in 1994, Cronyn continued to work, most especially in Marvin’s Room (1996), where, as Leonardo DiCaprio’s dying grandfather, he was almost wordless, but as eloquent as ever.

He is survived by his second wife, Susan Cooper, three children from his first marriage and two stepchildren.

· Hume Cronyn, actor, born July 18 1911; died June 15 2003