Karl Malden was born in 1912 in Chicago. In 1934 he began trainig to be an actor at the Goodman School in his native city. He began acting on Broadway in 1937. He scored a big success in Artur Miller’s “All My Sons”. He began his film career in Moss Hart’s “Winged Victory” in 1945 and a few years later had a very profilic career in film. His movie highlights include “A Streetcar Named Desire”, “Halls of Montezuma”, “I Confess”, “On the Waterfront”, “Baby Doll”, “Fear Strikes Out”, “Pollyanna”, “Come Fly With Me” and “Patton”. He had a spectactular television success with Michael Douglas in “The Streets of San Francisco”. Karl Malden died in 2009 at the age of 97.

His “Guardian” obituary by Ronald Bergan:

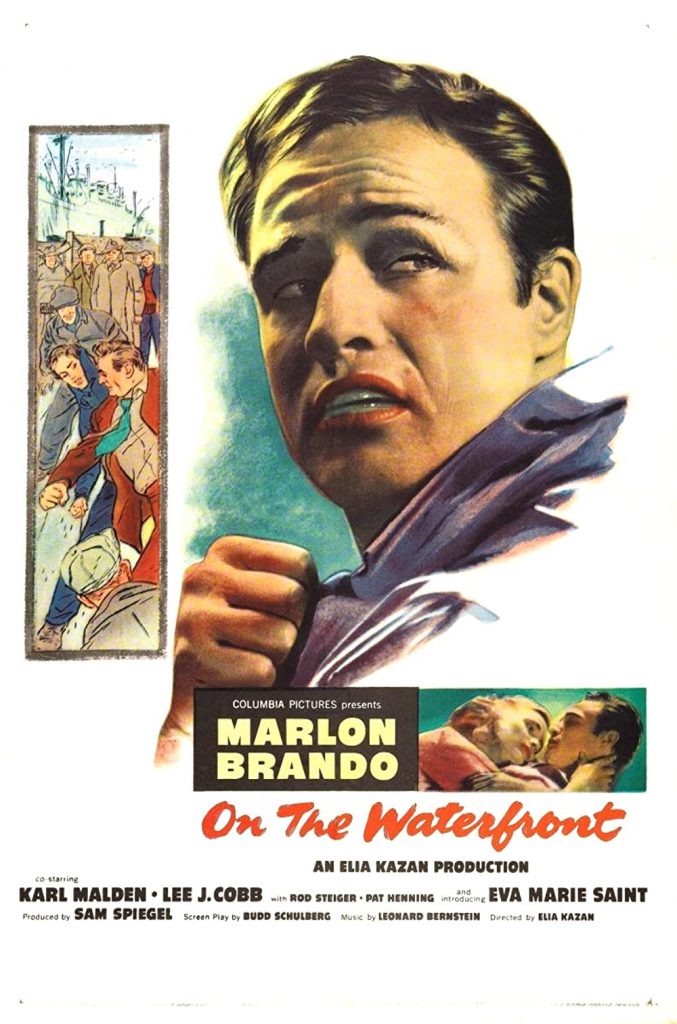

For more than six decades Karl Malden, who has died at the age of 97, brought his Method-trained acting talents to bear on powerhouse performances on screen, notably for Elia Kazan in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), for which he won an Oscar, and On The Waterfront (1954), as well as his mature cop in the long-running TV series The Streets of San Franscisco in the 1970s.

Like WC Fields and Jimmy Durante, Malden had one of the most celebrated non-Roman noses in cinema. But whereas those of the two former entertainers produced a comic effect — Fields’s bibulous one looked as if it were stuck on like a clown’s, and Durante’s schnozzle was like a carnival mask — Malden’s proboscis seemed to add dramatic intensity to his performances. The more impassioned he became, the more the nose seemed to go on red alert.

This particularity of Malden’s appearance came about because he broke his nose twice as a high school American footballer. He had won a scholarship to Arkansas state teachers college, but had to leave to support himself and his family by working in a steel mill in Gary, Indiana. Born Mladen Sekulovich in Chicago, he was brought up in Gary, where his father, Peter Sekulovich, who had been a provincial actor in Yugoslavia, was working in the mill. Karl also delivered milk to make money to go to New York, where he hoped to satisfy his ambition to become an actor.

In New York, in the late 1930s, Malden joined the leftist Group Theatre, which was devoted to social realities and ensemble acting inspired by Stanislavsky at the Moscow Arts Theatre. Its leading light was the playwright Clifford Odets, in whose Golden Boy (1937) Malden appeared as a boxing manager. Also in the play was future director Kazan, with whom Malden was to work several times on stage and screen.

After Malden returned from army service during the second world war, he became a member of the newly formed Actors’ Studio, among whom were Marlon Brando and Richard Widmark. In 1947, on Broadway, Kazan, one of the founders of the Actors’ Studio, directed Malden in both Arthur Miller’s All My Sons and Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. The latter, in which Malden played Mitch opposite Brando and Jessica Tandy, led to a contract with 20th Century-Fox.

At the studio, Malden played vivid supporting roles in gritty thrillers such as Henry Hathaway’s 13 Rue Madeleine and The Kiss Of Death, Kazan’s Boomerang (all 1947) and Otto Preminger’s Where The Sidewalk Ends (1950). He also added realism to the Henry King western The Gunfighter, and Lewis Milestone’s war drama Halls Of Montezuma (both 1950).

During the same period, Malden appeared on Broadway as the Button Moulder in Lee Strasberg’s production of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, with John Garfield in the title role, and in Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms, as the domineering patriarch.

In 1951, Malden won the best supporting actor Oscar for reprising his stage role of Mitch, the shy, sweaty, balding middle-aged suitor of Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh) in A Streetcar Named Desire, again directed by Kazan. The most pitiless moment comes when Malden snaps on the naked bulb to expose Blanche’s ageing, powdered face to “reality”. “I don’t want the light, I want magic,” she entreats. “Oh, I knew you weren’t 16. But I was fool enough to believe you was straight,” he replies, his voice trembling with emotion.

The following year, he was playing a man caught in the clutches of a femme fatale (Jennifer Jones) in King Vidor’s Ruby Gentry and then the persistent cop who suspects Montgomery Clift’s priest of murder in Alfred Hitchcock’s I Confess (1953). If it were not already evident from his performances, the intelligence of an actor like Malden could be deduced from the number of major directors with whom he worked. In his best and most personal work he succeeded in exploring depths of moral ambiguity rare in the commercial cinema.

He gave two further powerful performances for Kazan. In On The Waterfront, he was Oscar-nominated for his role as the tough, crusading dockland Catholic priest, Father Barry, who helps bring an end to crooked waterfront politics. Even better was his wonderful portrayal of Archie Lee, the cotton-mill owner husband of a backward thumb-sucking virgin child bride (Carroll Baker) in Baby Doll (1956).

Driven frantic by her refusal to allow him into her bed, even though it is a child’s cot, too small for her ample proportions, the boorish, white-trash character is turned by Malden into a tragicomic figure uttering a sustained cry of sexual frustration. “Most actors want to be heroic, sexy and noble. Karl doesn’t mind if you to make him look silly. He is more a real person than an actor,” Kazan remarked at the time.

In Robert Mulligan’s Fear Strikes Out (1956), he played a well-meaning but domineering father who drives his highly strung son (Anthony Perkins) to the edge of madness — the two leads successfully vying with each other in the emotional stakes.

Apart from having taken over much of the direction from Delmer Daves of the Gary Cooper western The Hanging Tree (1958), in which he had the role of a lecherous half-wit, Malden was credited with one film as director, Time Limit (1957), starring his friend Richard Widmark. This Korean war drama was as taut and gripping as one of his performances, containing many of the pros and cons of his acting style, fervent but sometimes overemphatic.

Brando also directed one film, One Eyed Jacks (1961), a rambling self-indulgent revenge western in which Malden played the heavy, a former outlaw who has betrayed Brando, and who had become a respectable sheriff. Brando’s brooding, somnolent performance was counter-balanced by Malden’s grinning, extrovert one.

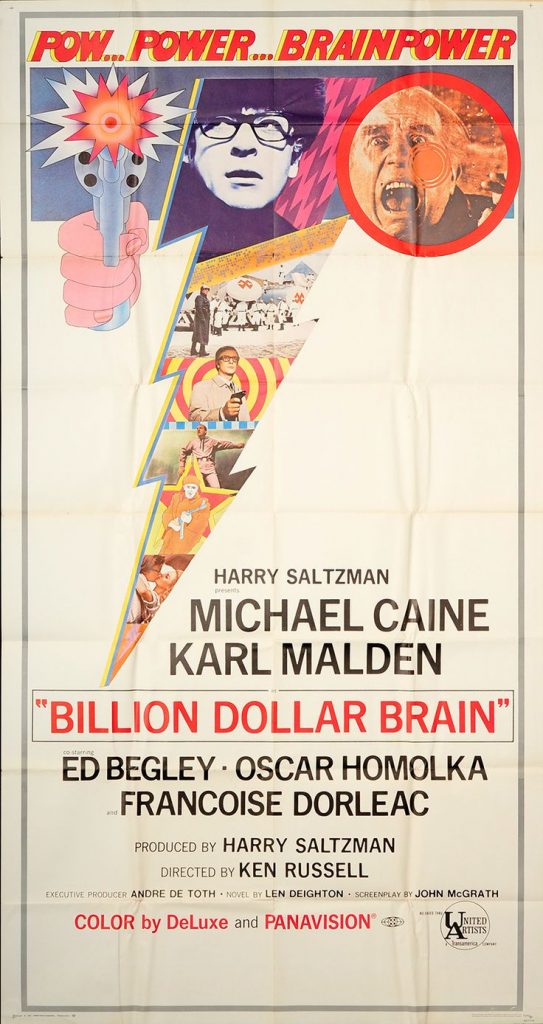

Included among Malden’s many varied roles in the 1960s were in two films by John Frankenheimer; as the drunken father in All Fall Down, and the prison warder in Birdman of Alcatraz (both 1962), and was utterly charming in his only musical, Mervyn LeRoy’s Gypsy (1962), though the one number which he got to sing, Together, with Rosalind Russell and Natalie Wood, was cut from the final print. He was also the weak double-dealer in Norman Jewison’s The Cincinnati Kid (1965).

For much of the 1970s Malden was busy playing the veteran police officer Detective Lieutenant Mike Stone in The Streets of San Francisco on television. A widower with 23 years’ experience of the force, he was partnered by Michael Douglas as the 28-year-old Steve Keller, a college graduate.

This lively combination — wise old head versus eager young enthusiast — produced enough sparks to keep it going for five seasons. Before the series began, Kirk Douglas told his son, “If anyone can teach you how to act it’s Karl”.

The rest of his film career was rather patchy; he made up the cast of a few disaster films, turned up in Blake Edwards’s misconceived “existential” western The Wild Rovers (1971), appeared in the dire sequel The Sting II (1982), but made a convincing General Omar Bradley in Patton (1970), having spent some time with the general before taking on the role. His last appearance on screen was as a priest in an episode of The West Wing (2000).

From 1989 Malden was president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Ten years later, he urged the academy to award an honorary Oscar to Elia Kazan. This was bitterly opposed by many who had never forgiven Kazan for being a “friendly witness” before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. However, the apolitical Malden prevailed. “If anyone deserved this honorary award because of his talent and body of work, it was Kazan,” he remarked.

Malden, who is survived by his wife of more than 70 years, the former actor Mona Graham, and two daughters, once commented: “I’ve been incredibly lucky. I always knew I wasn’t a leading man — take a took at this face! But I felt: if I can make it the way I look, others can.”

The “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed here.