Gloria Grahame TCM Overview

The best of the 40’s floozies was Gloria Grahame. She was so good that she eased herself out of supporting roles into star parts – though not many of much variation.

She was usually cast as your friendly neighbourhood nympho. She as both tough and vulnerable, a combination not rare, but here at it’s most winning.” – David Shipman – “The Great Movie Stars – The Golden Years” (1972).

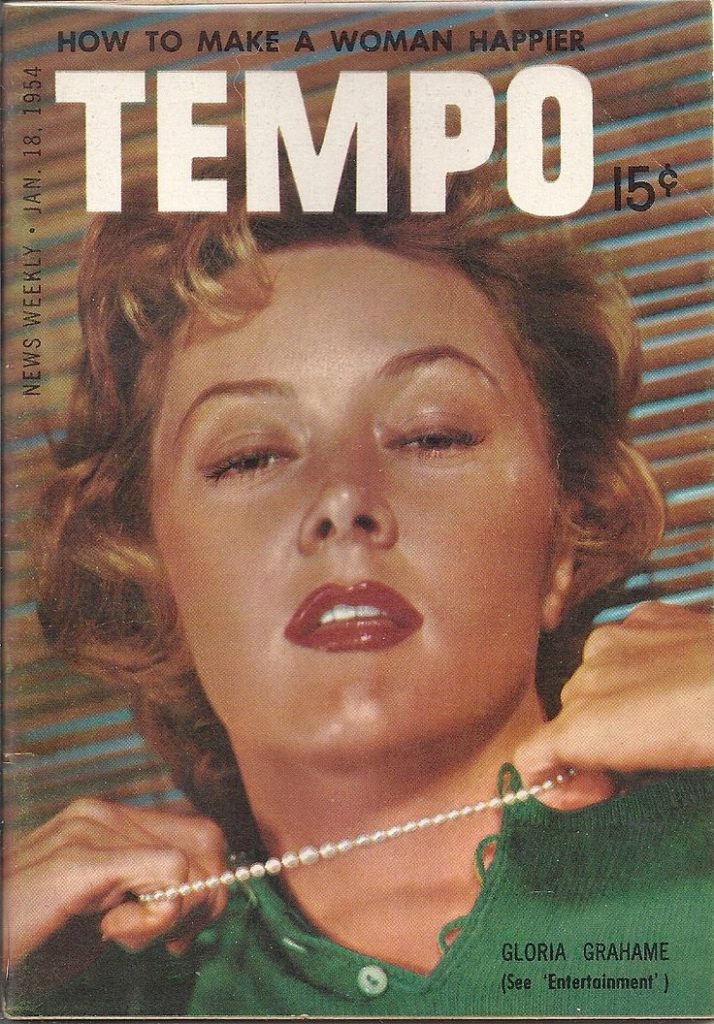

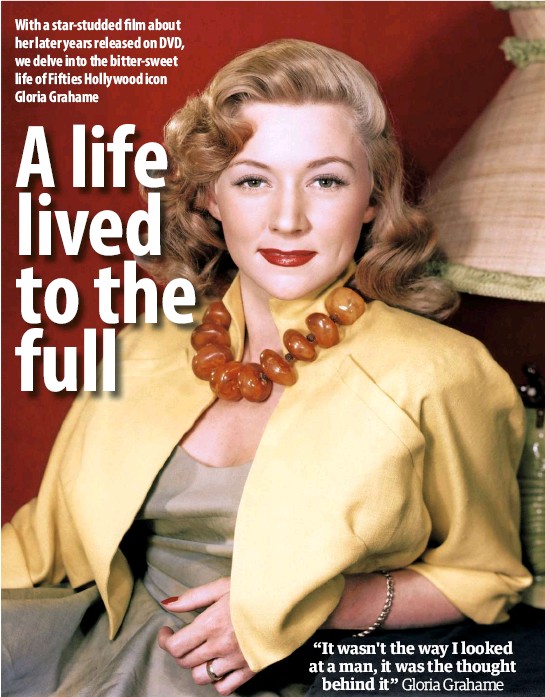

Gloria Grahame was born in 1923 in Los Angeles. She began her film career in the mid 1940’s and shone in a supporting role in the classic “It’s A Wonderful Life” in 1946. The following year she was Oscar nominated for her performance in “Crossfire”. She won the award for her role in “The Bad and the Beautiful” in 1952. One of the highlights of her career was her starring role in “Oklahoma” after which her cinema career waned suddenly. She died in 1981 but over the years she has achieved cult status for her many roles in film noir such as “The Big Heat”.

TCM Overview

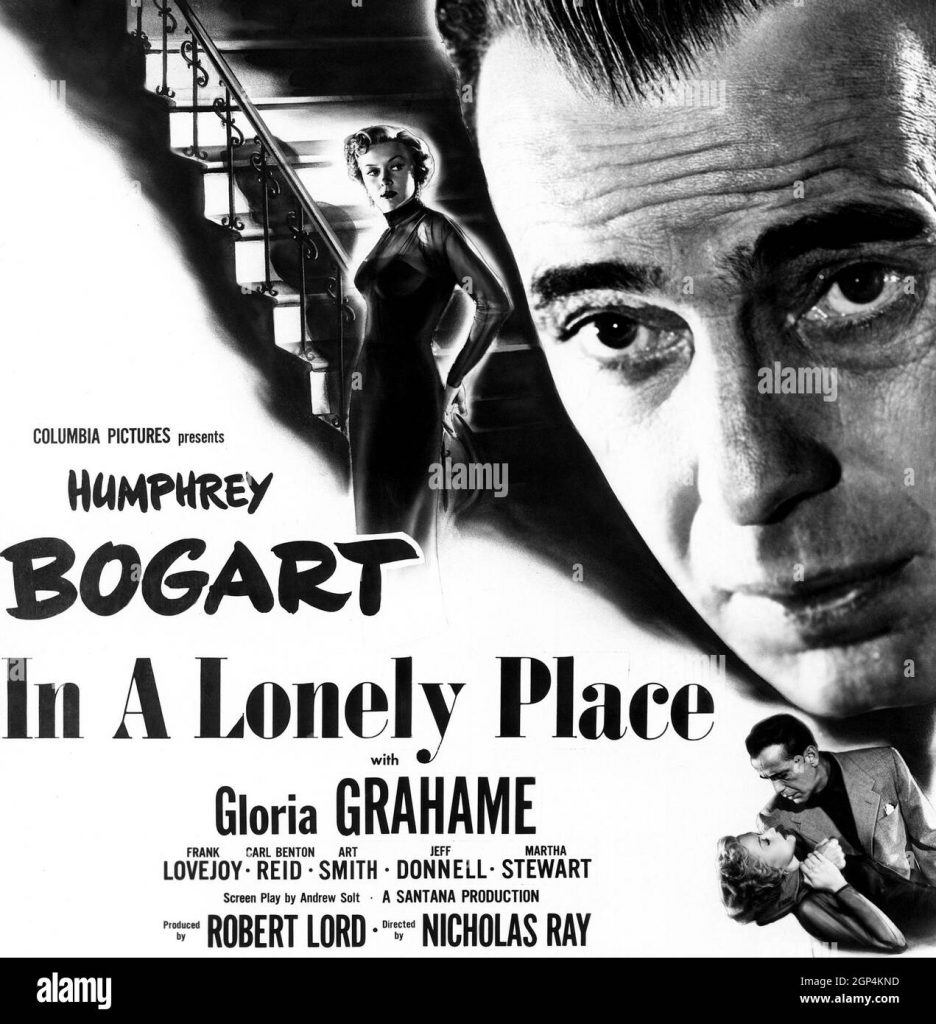

A femme fatale with extraordinary carnal allure, Gloria Grahame electrified moviegoers with her turns as venal, sexually aggressive women in such films as “Crossfire” (1947), “In a Lonely Place” (1950) and “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952), which earned her a Best Supporting Actress Oscar. A professional actress from childhood, Grahame began her career playing sexually confident if emotionally unstable women, and essentially repeated that role throughout the 1940s and 1950s, which marked her heyday in Hollywood.

Few actresses could present such an openly wanton image as Grahame, whose heavy-lidded eyes and permanently curled lip – the result of botched surgery – lent her a physical gravitas other actresses lacked. Her women were dangerous, without question, and potentially lethal if cornered, like her mob moll in “The Big Heat” (1953), who lurked through the film’s shadowy underworld on a hell-bent mission to avenge her disfigurement by Lee Marvin. Off-camera, Grahame had a reputation as an uncooperative performer, and her 1952 divorce from director Nicholas Ray, who discovered her in flagrante delicto with his 13-year-old stepson – whom Grahame would later marry in 1960 – left moviegoers appalled. Her career waned in the late 1950s, and she would labor through TV appearances and low-budget features until 1980, when she was felled by stomach cancer. But the best of her screen roles continued to burn on late-night TV and in revival houses, where her incendiary presence had lost none of its power to entrance – or to burn.

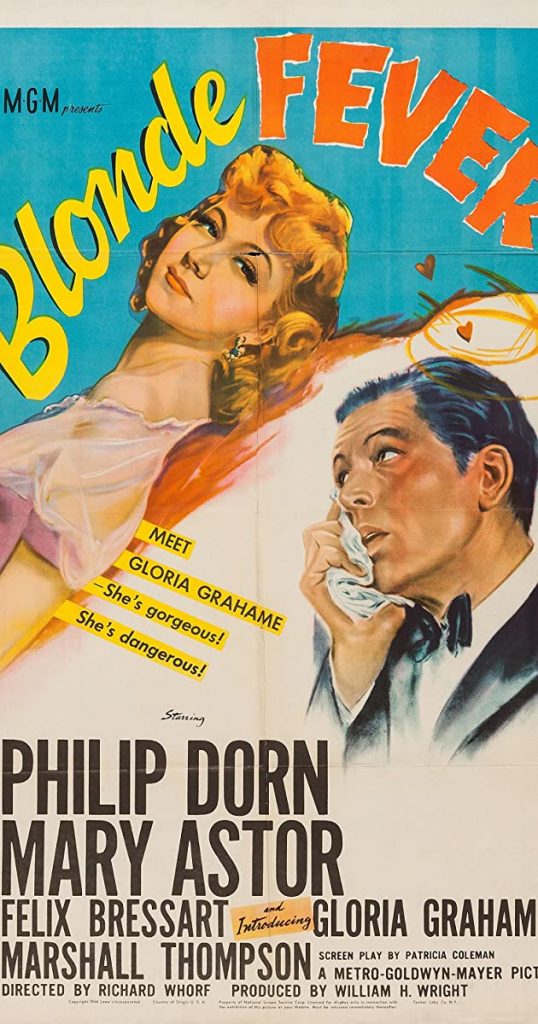

She was born Gloria Hallward in Los Angeles on Nov. 28, 1923, the daughter of architect and author Reginald Hallward and actress Jeanne McDougall, who performed under the name Jean Grahame. Her mother was also her acting coach, and Grahame began performing while still an adolescent before eventually graduating to Broadway. Even at this early age, critics made note of her earthy sexuality, which may have caught the attention of Louis B. Mayer. The MGM chief signed her to a contract that kicked off with the lightweight comedy “Blonde Fever” (1944), which featured Grahame as a gold-digging waitress on the make for lottery winner Philip Dorn.

Though unquestionably forgettable, her turn as Sally Murfin, whose curvaceous figure and blithe cluelessness blinded men from her predatory nature, would establish the tone for the majority of her screen roles. She cemented her screen presence with her turn as hapless good time girl Violet Bick, whom James Stewart’s George Bailey saved from a disgraceful fate, in Frank Capra’s “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1945). Despite its success, Grahame’s stay in the MGM stable was short-lived. By 1947, her contract was sold to RKO, where she landed a small but noteworthy part in the B-thriller “Crossfire” (1947), starring Robert Mitchum and Robert Ryan. Her performance, as an embittered dance hall girl who witnessed a murder, impressed audiences and earned her an Academy Award nomination. She lost the Oscar to Celeste Holm, but her status as one of the sultriest stars of film noir was now established. In 1948, she was cast as a neurotic singer allegedly shot by her Svengali-like coaches in director Nicholas Ray’s “A Woman’s Secret” (1948).

Ray became her second husband that year on the same day her divorce to actor Stanley Clements was finalized. He directed her in one of her most acclaimed films, 1950’s “In a Lonely Place,” as an aspiring actress whose wounded self-esteem stranded her in a tumultuous relationship with emotionally unstable screenwriter Humphrey Bogart.

In real life, Grahame’s self image was also fraught with anxiety. She disliked her looks, especially her mouth, and endured so many plastic surgeries on her upper lip that it was left paralyzed. To compensate for the disfigurement, she stuffed her lip with cotton or tissue, which left many a leading man confused after an onscreen clinch. Grahame also had a reputation for being “difficult,” a catch-all phrase used by gossip columnists and PR flacks to describe a wide panoply of behaviors, from confidence to outright anti-social behavior.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

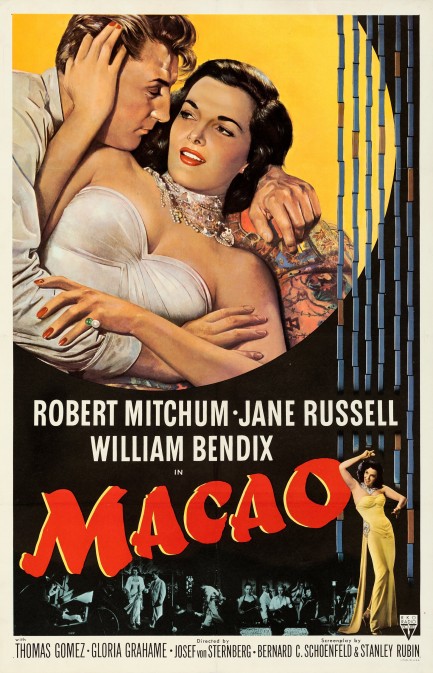

Unfortunately for Grahame, the label stuck, thanks to a combination of her movie image, clashes with co-stars like Bogart, and the scandalous end of her marriage to Ray in 1951. She was discovered by her husband in bed with her stepson, Anthony Ray, who was only 13 at the time. At the time, the married couple was completing a glossy noir-adventure, “Macao” (1952), with Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell, for producer Howard Hughes, which she handily stole as a brazen gangster’s moll.

She rebounded from the scandal with Vicente Minnelli’s “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952), a juicy Hollywood roman a clef with Grahame as harried screenwriter Dick Powell’s wife, whose effortless sexiness prevented him from completing the latest blockbuster for producer Kirk Douglas. She quickly followed this with equally compelling turns in “The Greatest Show on Earth” (1952) as a former bad girl-turned-circus performer, whose carnal past nearly cost her a chance at redemption with big top manager Charlton Heston.

Grahame was soon back on the dark side in “Sudden Fear” (1952) as the scheming, hot-blooded ex-girlfriend to Jack Palance’s psychopath in sheep’s clothing. All four films netted her rave reviews, but it was “The Bad and the Beautiful” that landed her the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. It did not, however, improve her public image; she stumbled on her way to the dais at the award show, and her disheveled appearance, due in part to the grueling schedule of her next picture, Fritz Lang’s “The Big Heat” (1953), prompted rumors that she was drunk. Additional stories swirled in the tabloids about her alleged disinterest in her Oscar, which she attempted to dispel in interviews, to no avail.

Though a demanding shoot, “The Big Heat” presented Grahame with her last great screen role: the acid-tongued, narcissistic girlfriend of vicious mob gunsel Lee Marvin, who infamously tossed a pot of boiling coffee in her face, leaving her hideously disfigured. Her performance, alternately monstrous and pitiable, was one of the most indelible of the film noir canon, and for most viewers, the one for which Grahame was best known. She would continue to mine the vein of the tragic wanton in several films, including Lang’s “Human Desire” (1954), a remake of Jean Renoir’s “Le Bete Humaine” (1938), and “Naked Alibi” (1954), to diminishing returns. Grahame’s face and figure had changed since her film debut, with the plastic surgery adding a heavy lisp to her speaking voice, so she was no longer convincing as a youthful sexpot.

She attempted a drastic image change with 1955’s “Oklahoma!” in which she was cast as Ado Annie. The film was more than a departure for Grahame than a complete left-field choice, as she had no singing voice to speak of, which required her key number, “I Cain’t Say No,” to be sung one note at a time and then reconstructed by the music editors. Grahame was also undergoing a traumatic divorce from director Cy Howard, as well as a custody struggle with Nicholas Ray for their son, Timothy, and the stress spilled over into her work in the film. She reportedly refused to learn her dance numbers and repeatedly upstaged other cast members. After physically attacking co-star Gene Nelson, she was declared persona non grata by her fellow actors, and word of her behavior soon spread throughout Hollywood. She would enjoy one last notable role as a semi-masochistic woman who fell for racist crook Robert Ryan in “Odds Against Tomorrow” (1959). The following year, she outdid her own previous scandal record by marrying Anthony Ray, her former stepson-in-law, in 1960. She bore him sons in 1963 and 1965.

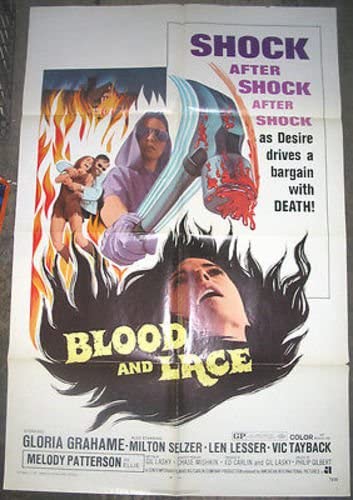

Grahame worked steadily in television throughout the 1960s before disappearing for a period at the end of the decade, during which she was rumored to have suffered a breakdown and spent time in an institution. She resurfaced in the early 1970s in a string of TV movies and low-budget features, including the grisly “Blood and Lace” (1971) and “Mama’s Dirty Girls” (1974). After divorcing Anthony Ray in 1974, she rebounded, after a fashion, with a trio of turns as unstable older women in “Chilly Scenes of Winter” (1979), “A Nightingale Sang in Berkley Square” (1979) and “Melvin and Howard” (1980), with the latter merely a glorified cameo. In her final years, she performed the classics in regional theater before learning that she had stomach cancer in 1980. Grahame refused to stop working, but suffered a collapse during rehearsal of a play in London. While undergoing a routine operation to drain fluids from an inoperable tumor in her stomach, her surgeon accidentally perforated her bowl. Peritonitis set in, and she was flown home to New York by her romantic companion, actor Peter Turner. After several agonizing days, Grahame died on Oct. 5, 1981 at the age of 57.