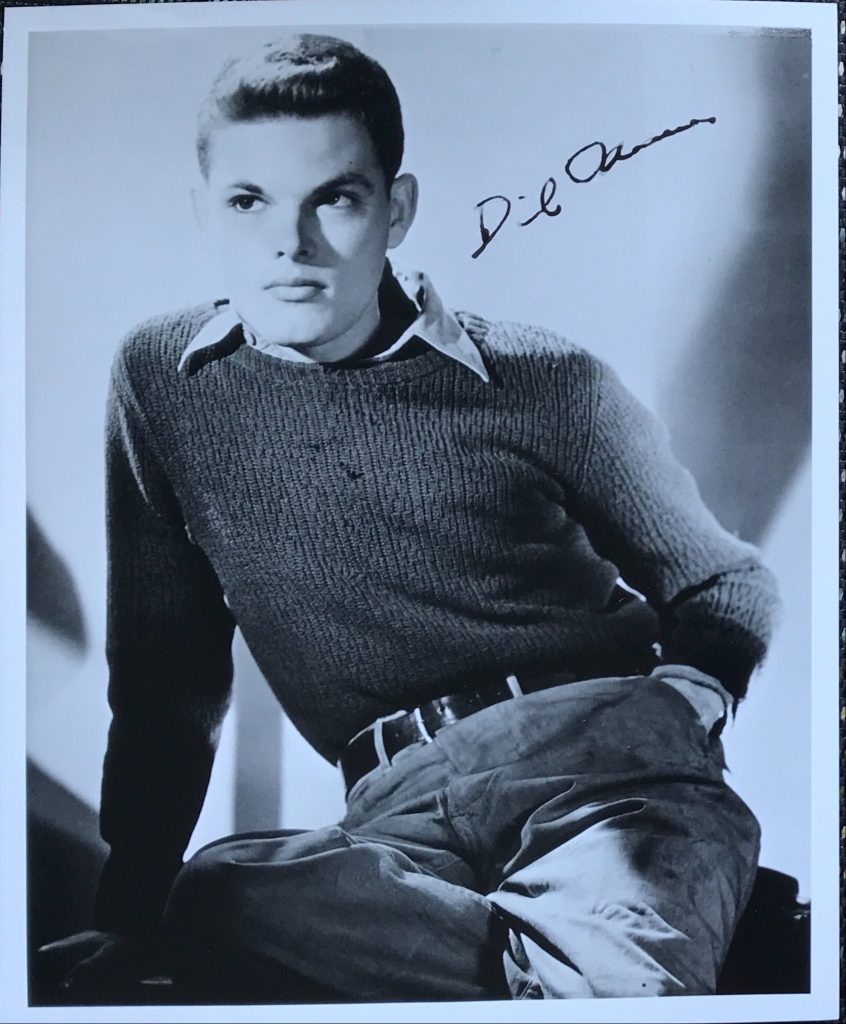

The Guardian obituary by Ronald Bergan in 2015

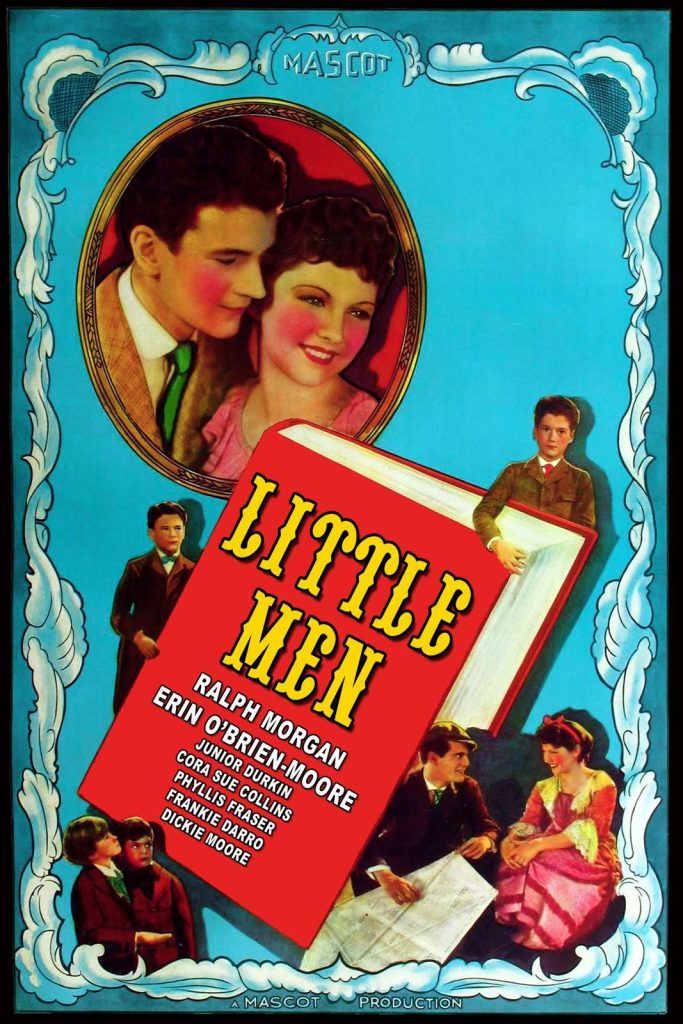

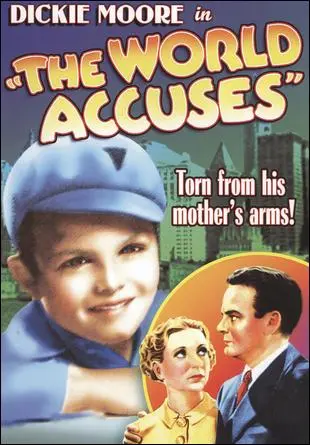

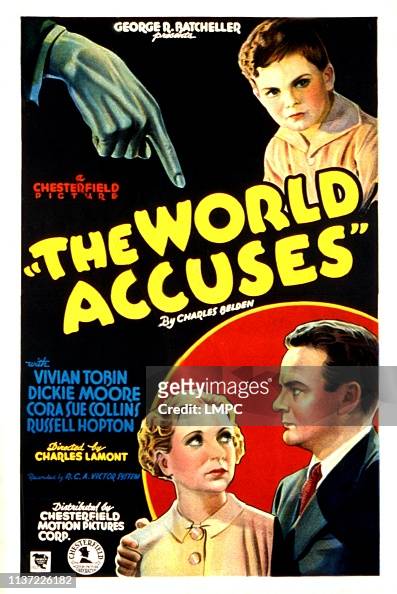

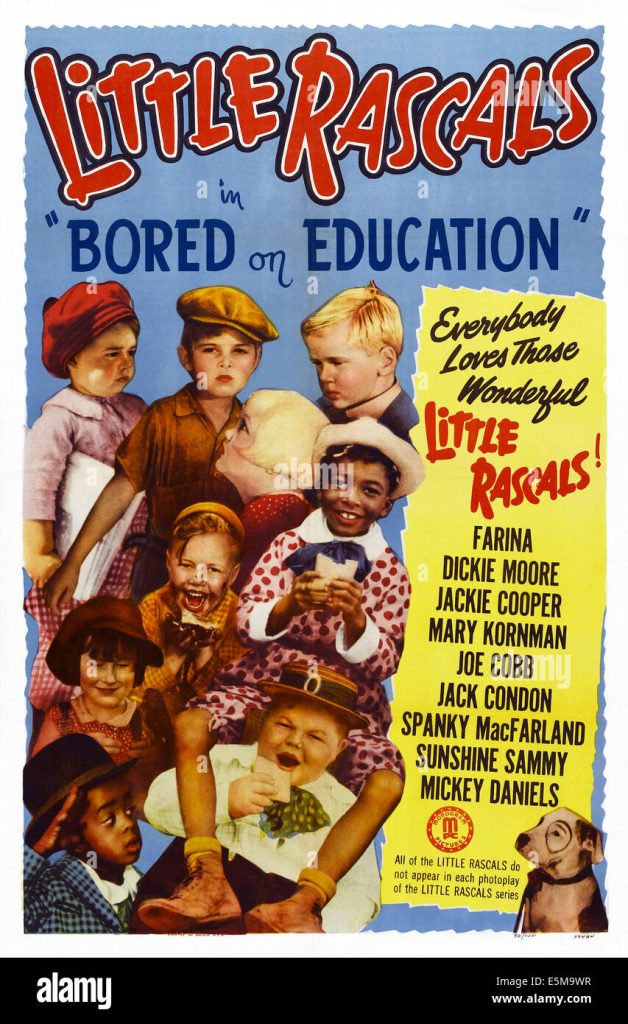

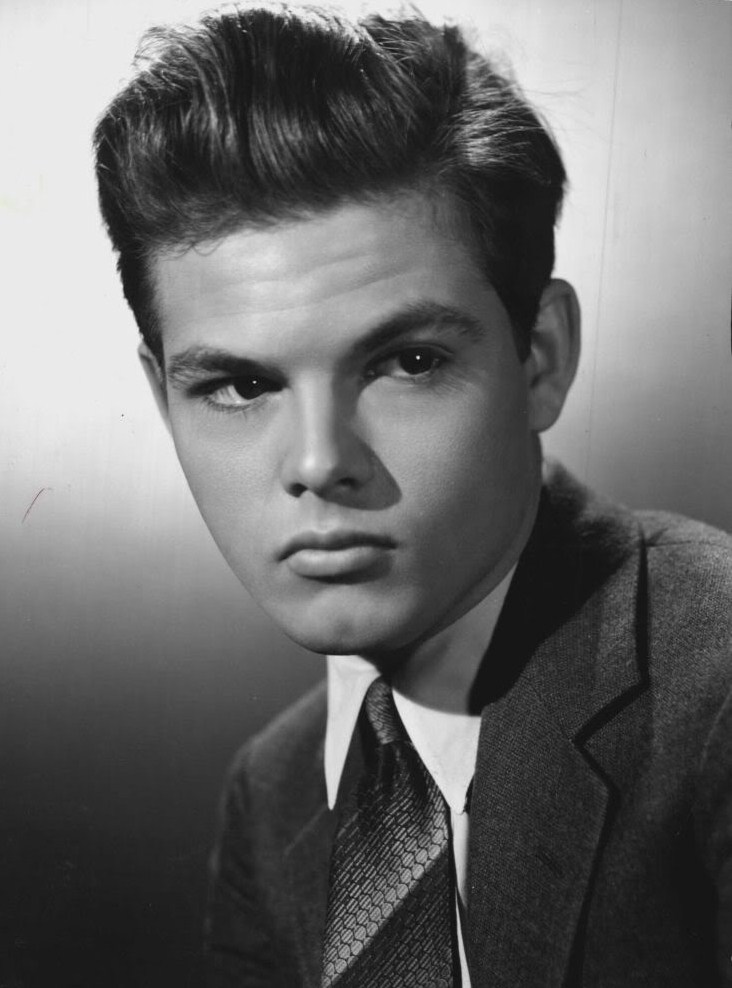

Dickie Moore, who has died aged 89, was an angelic-looking child actor whose big brown eyes lit up many a movie melodrama in the 1930s. From the age of four, his cherubic features got him cast regularly as a poor little rich boy, the son of a single parent or the child being fought over by estranged parents. Rarely a brat, Moore was the least rascally of the group of mischievous kids in the short film comedy series Our Gang (renamed Little Rascals for TV), six episodes of which he appeared in (1932-33).

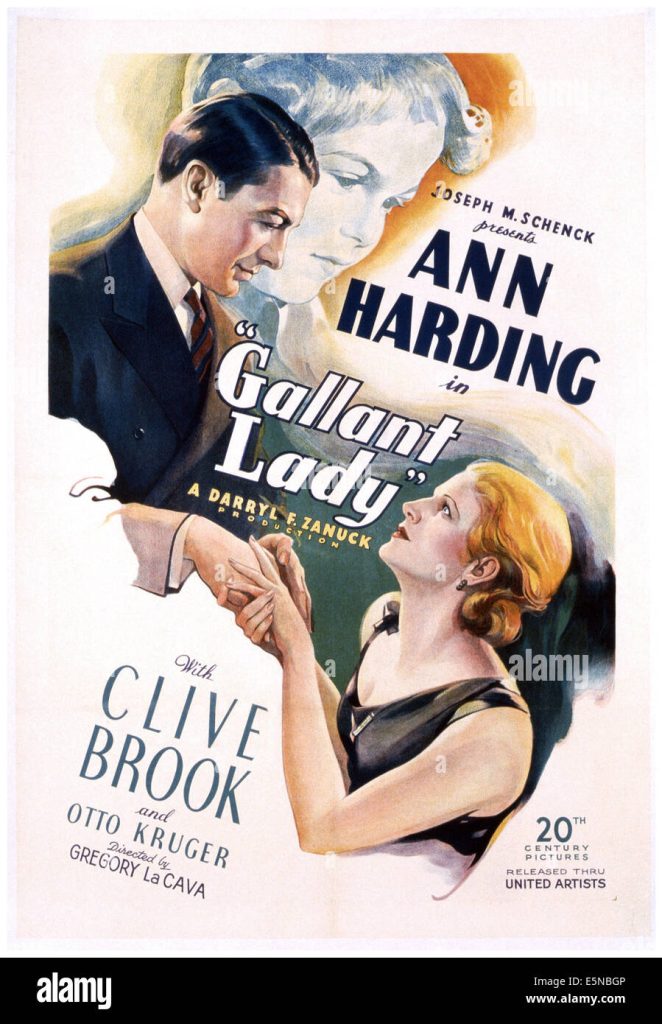

However, after having acted with stars of the magnitude of James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Barbara Stanwyck, Marlene Dietrich and Paul Muni, Moore managed the awkward transition to puberty and a later adaptation to a career in public relations.

Born conveniently in Los Angeles, Moore made his screen debut at the age of 11 months in the silent film The Beloved Rogue (1927), representing John Barrymore’s character, the poet François Villon, as a baby. Two years later, he was already in demand from different studios, which helped to support his parents while his banker father was unemployed during the Depression.

He soon got his first review in the New York Times for Passion Flower (1930). “Dickie Moore is charming … His chatter is natural because he means most of what he is called upon to say … Almost every time Dickie spoke a line the audience was convulsed with laughter.”

In 1931, Moore was the half-Native American child of Warner Baxter and Lupe Vélez in Cecil B DeMille’s The Squaw Man (later known as The White Man). According to Moore, “DeMille was a complete and total egotist who didn’t give a damn about anyone but himself. He hit me. I was a five-year-old kid and he hit me!” Moore had more pleasant memories of Stanwyck when playing her son, the centre of his mother’s existence, in William Wellman’s So Big! (1932). He also had a key role in Josef von Sternberg’s Blonde Venus (1932), bright as a button trying to reunite his separated parents (Dietrich and Herbert Marshall).

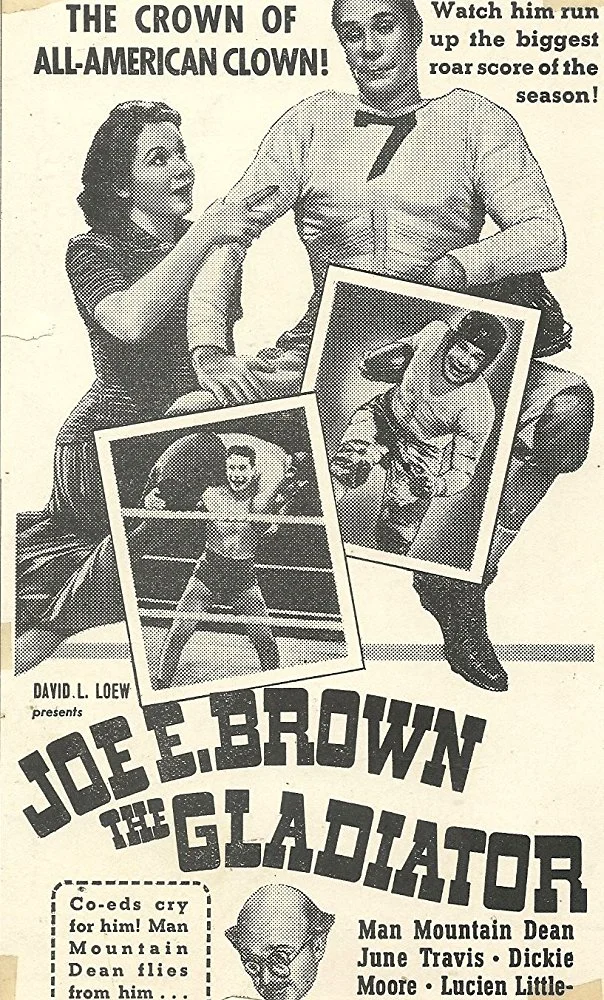

In Disorderly Conduct (1932), Moore plays cop Spencer Tracy’s nephew, who is dressed in a little policeman’s uniform when he is accidentally shot and killed by a gangster. With Tracy again, Moore is a wide-eyed baseball fan in Frank Borzage’s Man’s Castle (1933).

It was not surprising that Moore was chosen to play the title role in Oliver Twist (1933), the second film adaptation of the Charles Dickens novel. (In the 1922 silent version, the role had been taken by Jackie Coogan.) Oliver is described in the film (and novel) as “a pale, thin child, somewhat diminutive in stature and decidedly small in circumference”. However, Moore, though small, seems rather well fed and decidedly cheery, his naturalness contrasting with the rather hammy performances around him.

Already a veteran of more than 50 features, when Moore reached his 10th birthday he appeared in two Warner Bros biopics directed by William Dieterle and starring Muni: The Story of Louis Pasteur (1936) – in which he is a patient bitten by a rabid dog and cured by Pasteur – and as Captain Alfred Dreyfus’s son in The Life of Emile Zola (1937).

Yet, despite his success, he recalled that, “Every time I got in front of the cameras, I felt like it was an x-ray machine. It was like I was ashamed of or embarrassed about what was revealed to everyone who was watching me.”

Moving into his teens, when handsome replaced cute, Moore played reluctant soldier Gary Cooper’s brother in Howard Hawks’s Sergeant York (1941). This was followed by Miss Annie Rooney (1942), in which he was cast opposite another former child star, Shirley Temple, three years his junior and also suffering growing pains. The film contained the over-publicised scene in which Moore as a bespectacled rich boy administers Temple’s first romantic screen kiss; actually a chaste peck on her dimpled cheek. At one stage, she tells her mother, “He isn’t a boy. He’s 16.”

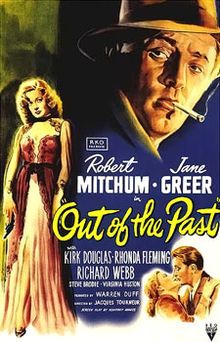

Moore, going on 18, continued in movies, notably as a premature playboy (Don Ameche took the role of Henry Van Cleve as an adult) in Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait (1943), until he served in the second world war as a correspondent for Stars and Stripes magazine in the Pacific. After attending Los Angeles City College, majoring in journalism, he returned to acting in Jacques Tourneur’s splendid film noir Out of the Past (1947), in which he was very touching as Robert Mitchum’s deaf and speech-impaired gas station assistant. In 1949, Moore produced and narrated an Oscar-nominated short called Boy and the Eagle, in which he played a disabled boy who discovers a wounded bald eagle and nurses it back to health, until one day it saves his life.

Moore crowned his stage career on Broadway in George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan (1956-57) by playing Brother Martin Ladvenu, a sympathetic young priest who wants to save Joan’s life. Some years later, in 1966, after a battle against alcohol and drugs, Moore founded a public relations firm, Dick Moore and Associates, which he ran until 2010.

In 1984, Moore wrote Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star (But Don’t Have Sex or Take the Car), in which he interviewed more than 30 former child stars, comparing their lives with his. In almost all cases what he discovered was an adult life with more than its share of breakdowns and failed marriages. Moore was divorced twice, finally finding happiness with the former MGM teen singing star Jane Powell, whom he met when interviewing her for the book. They were married in 1988.

She survives him, as does a son, Kevin, from his first marriage, and a sister, Pat.

• Dickie Moore (John Richard Moore Jr), actor, born 12 September 1925; died 7 September 2015