“Independent” obituary from 2006:

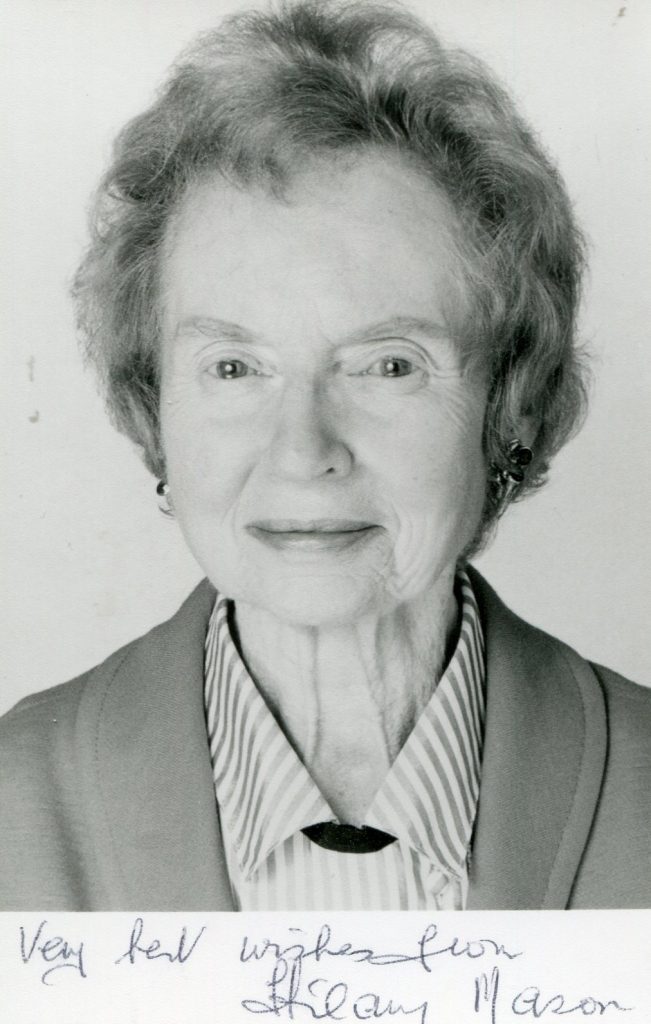

Hilary Lavender Mason, actress: born Birmingham 4 September 1917; married Roger Ostime; died Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire 5 September 2006.

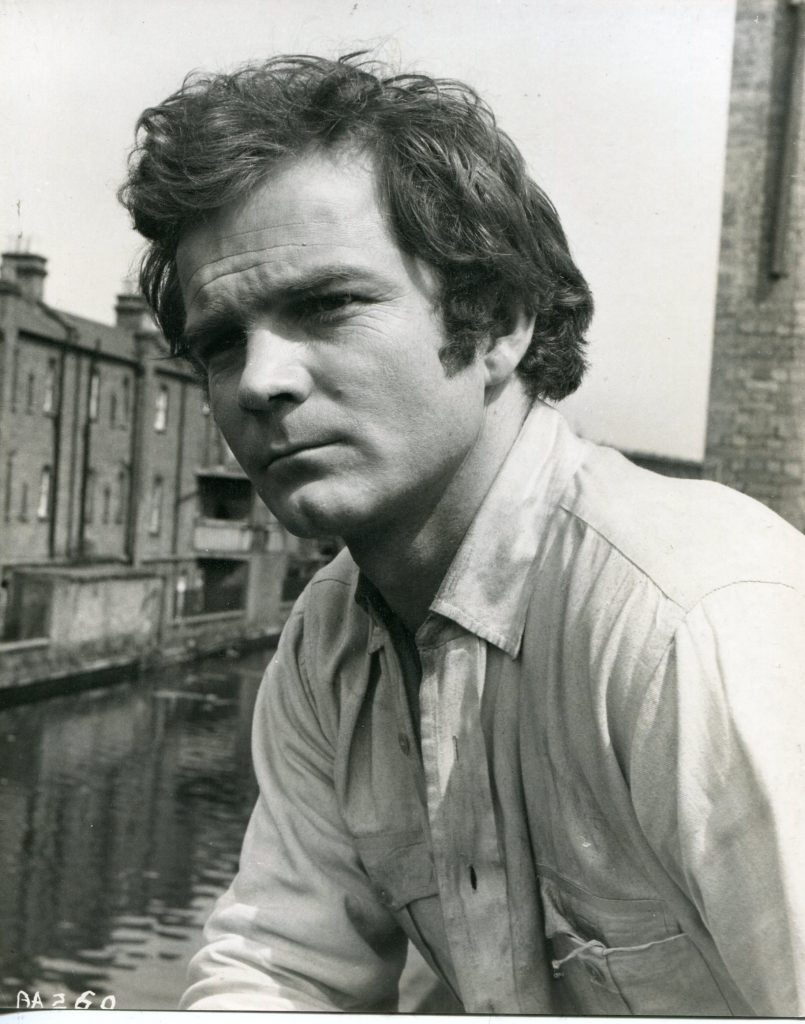

Although a prolific television character actress for almost half a century, Hilary Mason will be best remembered on screen as the blind, psychic Heather in the macabre supernatural thriller “Don’t Look Now”. The 1973 film starred Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland as John and Laura Baxter, a grieving couple holidaying in a wintry Venice after the death of their daughter, Christine, who was drowned in the garden pond while wearing a shiny, red mackintosh. When Laura meets the two spinster sisters in a restaurant toilet, she is shocked to be told that Heather has seen her daughter. “I’ve seen her and she wants you to know that she’s happy,” says the old woman: I’ve seen your little girl, sitting between you and your husband, and she was laughing. Yes, oh, yes, she’s with you, my dear, and she’s laughing. She’s wearing a shiny little mac. She’s laughing, she’s laughing – she’s happy as can be. Later, Laura attends a seance with the sisters and – when Heather gets what she claims to be a message from Christine – is disturbed to be told that her husband, John (Sutherland), is in danger. A sceptical John fails to heed the warning and in the final scenes of the film is murdered by a female dwarf in a red, hooded coat. Throughout this eerie film, based on a Daphne du Maurier short story, the director, Nicolas Roeg, leaves us unsure whether Mason’s chilling character really is a psychic or a con artist, particularly in a scene showing the sisters laughing after convincing Laura that they have contacted her daughter.

Born in Birmingham in 1917, Mason won a scholarship to the London School of Dramatic Art before gaining repertory theatre experience in Preston, Southport, York and Guildford. During the Second World War she performed with the troops entertainment organisation Ensa. Mason made her television début as Mrs Drummond in the drama series Thunder in the West (1957), and played Mrs Yapp in the Midlands-based local council serial Swizzlewick (1964) and Mrs Timothy in the soccer soap United! (1965-67), as well as taking two roles in Coronation Street. Following a bit-part as Mrs Ainsworth (1965), she was Derek Wilton’s mother (1976), who disapproved of her son’s relationship with the dithering Mavis Riley and insisted it must end – to no avail. Adept at character roles, Mason took eight different parts in Z Cars (1962-71) and another three in Dixon of Dock Green (1965, 1966, 1967), before playing Lady Boleyn in the acclaimed, six-part drama The Six Wives of Henry VIII (starring Keith Michell in the title role, 1970), Mrs Nickleby in Nicholas Nickleby (1977), Mrs Gummidge in David Copperfield (1986) and Mrs Fagge in Great Expectations (1989).

In comedy, she acted Mrs Booth, exasperated mother to the chalk-and-cheese twin brothers, in My Brother’s Keeper (1975-76) and Gladys (1990-94) in Maid Marian and Her Merry Men, the children’s series written by Tony Robinson – with Mason’s real-life husband, the actor Roger Ostime, taking the role of Gladys’s father in one episode. She also played Michael Palin’s mother in the Ripping Yarns episode “The Curse of the Claw” (1977). After her part in “Don’t Look Now”, Mason was cast in the horror films I Don’t Want To Be Born (acting Mrs Hyde, alongside Joan Collins as a stripper who gives birth to a “possessed” baby, 1975), Dolls (1987), Afraid of the Dark (1991) and Haunted (1995).

Anthony Hayward

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.