Bebe Daniels was born in 1901 in Dallas, Texas. At the age of 10 she starred in the silent film “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”. In the 1920’s she was under contract to Paramount Studios. Her talkie pictures included “My Past” in 1931 and “42nd Street” in 1933. In 1935 she moved to London and rebuilt her career there with her husband Ben Lyon with considerable success. They had a very popular BBC radio series “Life With the Lyons” which later made the transition to television. She died in 1971. Ben Lyon was born in 1901 in Atlanta, Georgia. “Flaming Youth” in 1923 bright him to fame. “Hell’s Angels” in 1930 is his most popularly remembered role.

Ben Lyon’s IMDB entry:

Ben Lyon was your average boyish, easy-going, highly appealing film personality of the Depression-era 1930s. Although he never rose above second-tier stardom, he would enjoy enduring success both here and in England. Born Ben Lyon, Jr. in Atlanta, Georgia, the future singer/actor was the son of a pianist-turned-businessman and youngest of four. Raised in Baltimore, he started performing in amateur productions as a teen before earning marquee value on Broadway opposite such stars as Jeanne Eagels.

Hollywood took notice of the baby-faced charmer and soon Ben was ingratiating filmgoers opposite silent film’s most honored leading ladies. He appeared with Pola Negri in Lily of the Dust (1924), Gloria Swanson in Wages of Virtue (1924), Barbara La Marr in The White Moth (1924), Mary Astor in The Pace That Thrills (1925) and Claudette Colbert, in her only silent feature, in For the Love of Mike (1927). He advanced easily into talkies and was particularly noteworthy as the dashing hero in Howard Hughes‘ Hell’s Angels (1930), in which Ben actually piloted his own plane (Ben had trained as a pilot during WWI) and filmed some of the airborne scenes for Hughes himself. That same year was also a banner year for him in his personal life after marrying Paramount Pictures film star Bebe Daniels, with whom he had appeared in Alias French Gertie (1930).

As both of their movie careers started to decline, the talented twosome decided to work up a husband-and-wife music hall and vaudeville act. They took their show to England and became a hit at the London Palladium. At one point he served in the U.S. Army Air Force and rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel in charge of Special Services for the U.S. Air Corps in England. Soldiers, sailors and airmen (from 1939) listened to Ben and Bebe weekly on the air waves with their popular, long-running BBC broadcast “Hi, Gang!” The couple remained in England throughout WWII performing on stage and doing their valid part to entertain and honor the troops.

After a brief postwar stay in Hollywood in 1946, where Ben had taken an executive position with Fox, the couple returned to England and headlined another popular 1950s radio show, “Life with the Lyons,” which spawned two family-styled films that included children Barbara Lyon and Richard Lyon. In the early 1960s Bebe suffered multiple strokes and left the limelight, passing away in 1971. Ben remarried (to former actressMarian Nixon) and settled in the US, where he died in 1979 of a heart attack while on vacation.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

Bebe Daniels’s IMDB entry:

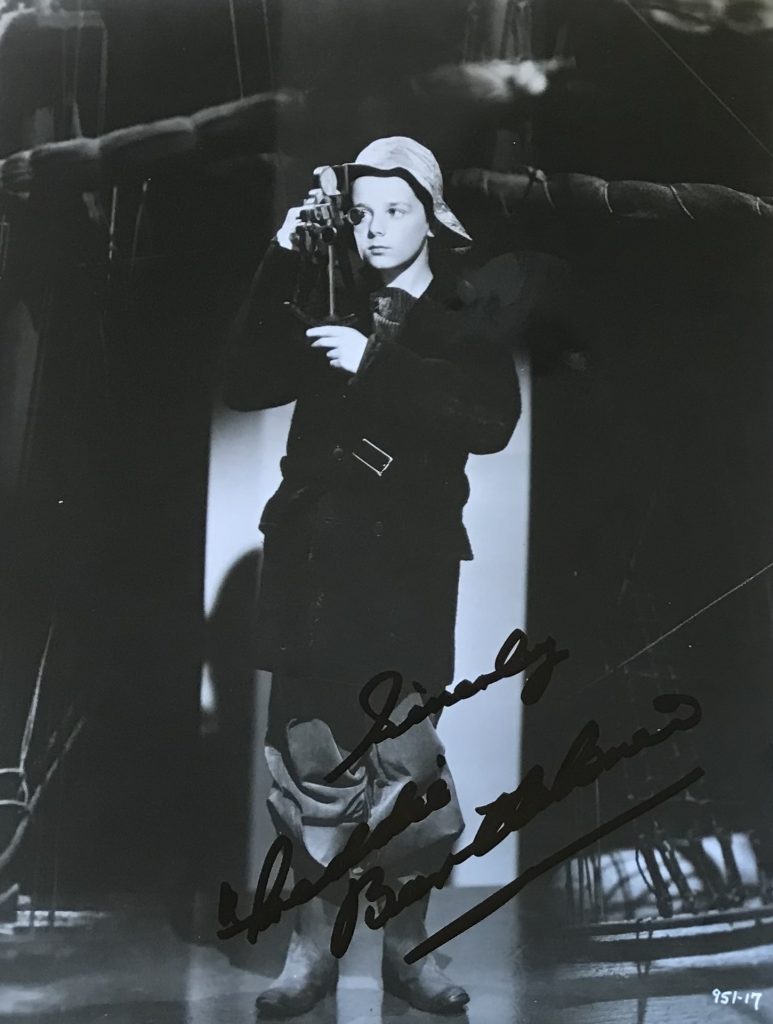

Bebe Daniels already had toured as an actor by the age of four in a stage production of Richard III the US, she had her first leading role at the age of seven and started her film career shortly after this in movies for Imperial, Pathe and others. At 14 she was already a film veteran, and was enlisted by Hal Roach to star as Harold Lloyd‘s leading lady in his “Lonesome Luke” shorts distributed by Pathe. Lloyd fell hard for Bebe and seriously considered marrying her— but her drive to pursue a film career along with her sense of independence clashed with HL’s Victorian definition of a wife. The two eventually broke up but would remain lifelong friends. Bebe was sought out for stardom by Cecil B. DeMille, who literally pestered her into signing with Paramount. Unlike many actors, the arrival of sound posed no problem for her; she had a beautiful singing voice and became a major musical star, with such hits like Rio Rita (1929) and 42nd Street (1933). In 1930 she married Ben Lyon, with whom she went to England in the mid-30s, where she became a successful Westend stage star and with her husband, a famous radio team. Her movie career drifted away after the mid-30s.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Stephan Eichenberg <eichenbe@fak-cbg.tu-muenchen.de>