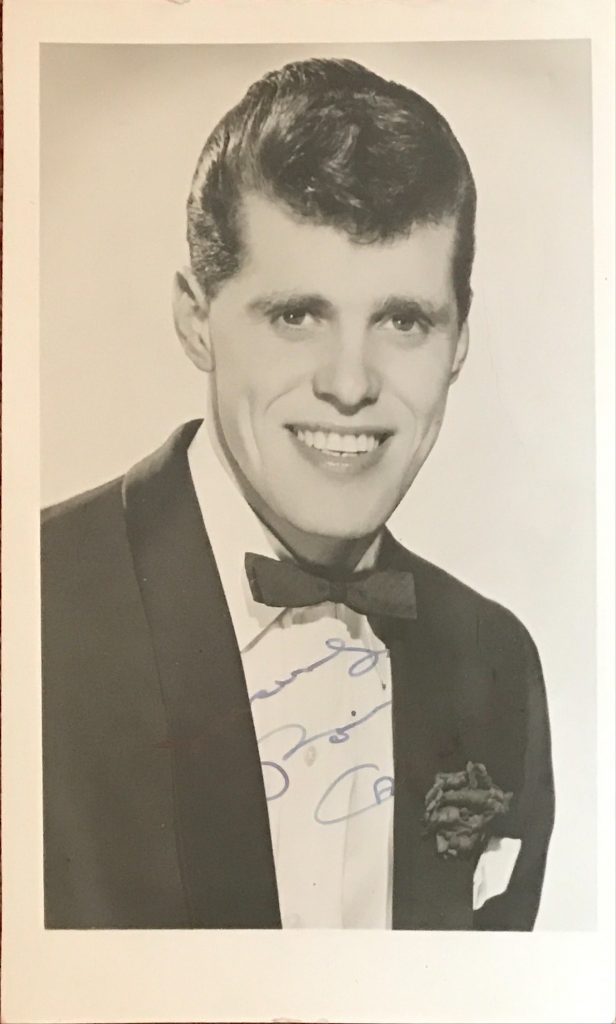

Ronnie Carroll was born in 1934 in Belfast. He sang for the U.K. in the 1963 Eurovision Contest with the song “Say Wonderful Things”. The same year he was featured in the film “Blind Corner”.

“Telegraph” obituary:

Ronnie Carroll, who has died aged 80, was a Belfast-born plumber’s son who became the only singer to represent Britain in the Eurovision Song Contest twice in a row; in later life he stood as a fringe candidate in several general and by-elections, during which he begged voters not to put a cross against his name in a bid to enter the Guinness Book of Records. Carroll first represented Great Britain and Northern Ireland in the Eurovision Song Contest in 1962. His jaunty entry, Ring-A-Ding Girl ( “Ring-ding-a-ding-a-ding Ding-ding / She’s my ring-a-ding girl”) was not quite ludicrous enough to win the competition, though it came a creditable fourth out of 16. The following year he returned with the slightly better Say Wonderful Things but still managed to come fourth.

The first song only reached No 46 in the British pop charts, though the latter made No 6, and Carroll had one more hit, Roses are Red, which peaked at No 3 in 1962. But then, for all but the most dedicated Carroll fans, the trail went cold. After his showbiz career ended, a nightclub venture in Grenada, and drinking and gambling habits, combined to ruin him. At one point Carroll was reduced to running a hot food stall in Camden. He resurfaced as the Emerald Rainbow Islands Dream Ticket Party candidate for the 1997 Uxbridge by-election when, despite his determined efforts to score “nul points”, singing what he hoped would be a new hit single: “Don’t Vote for Me, Reg and Tina!”, 30 spoilsports put their cross against his name. “There’s nothing more demoralising than aiming low and missing,” he reflected.

He was born Ronnie Cleghorn on August 18 1934 in Roslyn Street, East Belfast, and first hit the big time when he won a “Hollywood doubles” competition at the Belfast Hippodrome, after switching from impersonating Frank Sinatra to the gravel-voiced Nat King Cole, fully blacked up, having contracted a bad chest infection. “I kept listening to Nat’s records until I got it right, and when I was introduced at the Hippodrome as Nat King Cole in the final, after doing Sinatra in the heat, it brought the house down,” he recalled. His success led to a place on the Hollywood Doubles touring stage show and in 1956 he had his first big hit with Walk Hand in Hand, which reached No 13 in the charts and earned him an appearance on the BBC programme Camera One. In 1959 he helped to launch the pop programme Oh Boy! with a 17-year-old Cliff Richard and Marty Wilde. By this time Carroll was something of a teen pop idol. “It might seem hard to believe,” he said in 2008, “but … screaming girls would climb on to trains as I was pulling into stations and they’d come in droves for me backstage. Droves. I had as much sex as any man could wish for.”

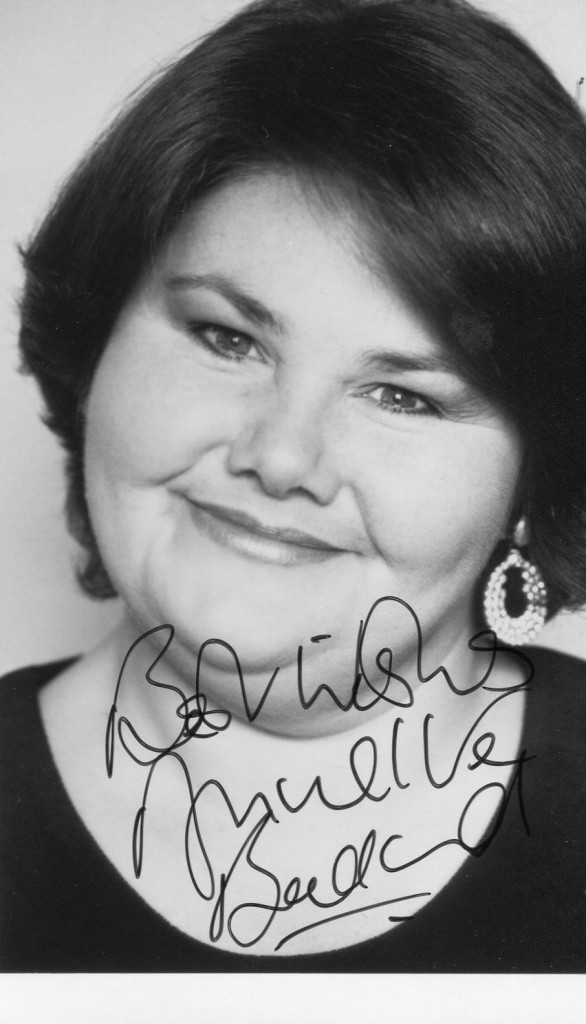

By the early 1960s he had married his first wife, the singer and actress Millicent Martin. But by the middle of the decade a youthful addiction to “pitch and toss” had developed into something more serious. On one occasion he flew to Las Vegas and blew £5,000 on the craps table in 20 minutes. “I walked out and had only enough for my cab fare,” he recalled. “I got back on a plane and flew to London. When I arrived home Millie said: ‘Did you have a good night?’ I replied: ‘Yes.’ ” The end of his marriage to Millicent Martin in the mid-1960s signalled the beginning of the end of his performing career . To console himself, Carroll hit the bottle.

When Sean Connery called round, he recalled, “I gave Sean a bottle of scotch and I had a bottle of vodka and after a few hours he said: ‘There’s a woman I fancy in Paris.’ But he couldn’t get off the floor so I phoned her and said: ‘Sean wonders whether you’d come over for a drink.’ Then I phoned a girl I liked, but she told me where to go.” After marrying his second wife, the Olympic runner June Paul, Carroll headed to the island of Grenada in 1972, to run a nightclub. But “there was a revolution in Grenada when we were there and we had sunk every penny we had into the nightclub,” he recalled. “There were no tourists left and we had no money to carry on.” Back in Britain Carroll continued to perform occasionally at holiday camps,ut eventually abandoned singing for a more profitable hot sausage stall at Camden Market. This he later combined with helping to run the Everyman Cinema and Jazz Club in Hampstead. When his second marriage ended, Carroll married and divorced a third wife, South African-born Glenda Kentridge.

His motivation for entering the political arena stemmed from a promise made to the raconteur and wit Peter Cook shortly before he died. “He told me: ‘Ronald, you must stand, promise me you will stand.’ Soon after that I thought, what have I done? Then he went and died on me. But a promise is a promise.” From 1997 he stood in several elections for “anti-politics” parties of various names, founded by the veteran environmental campaigner “Rainbow George” Weiss. In the 2005 general election he stood for the Vote For Yourself Rainbow Dream Ticket Party in Belfast, and released a “comeback” album, Back on Song, which he described as “a soup bowl of feelings I’ve had for women – and family and animals – going back decades”. He had been planning to stand as a candidate in next month’s general election in the marginal Hampstead & Kilburn constituency as the “Euro-visionary” candidate. In a quirk of electoral law his name will still appear on the ballot paper which means that he could, theoretically, still win on May 7. Ronnie Carroll is survived by three sons and a daughter.

The above “Telegraph” obituary can also be accessed online here.