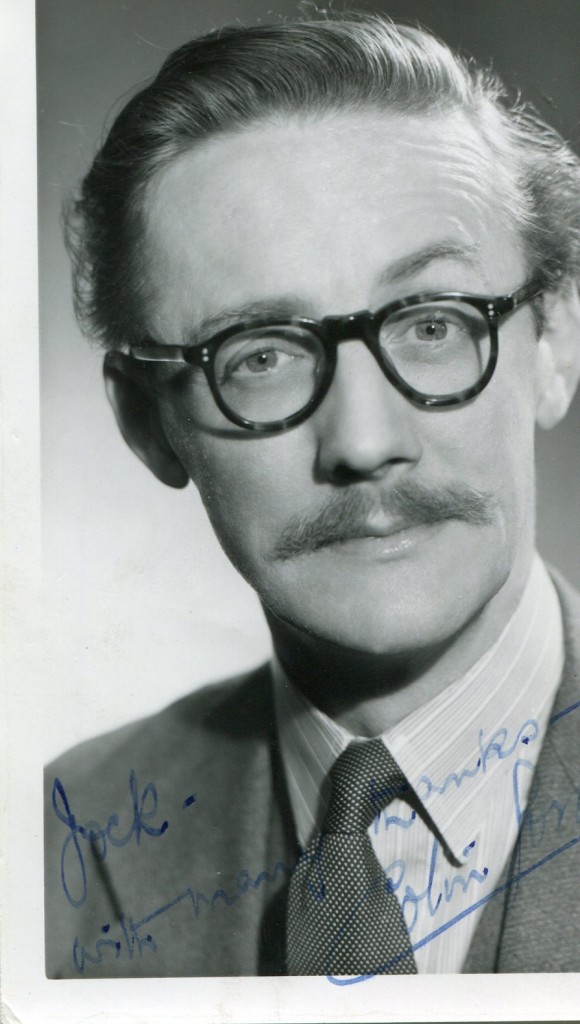

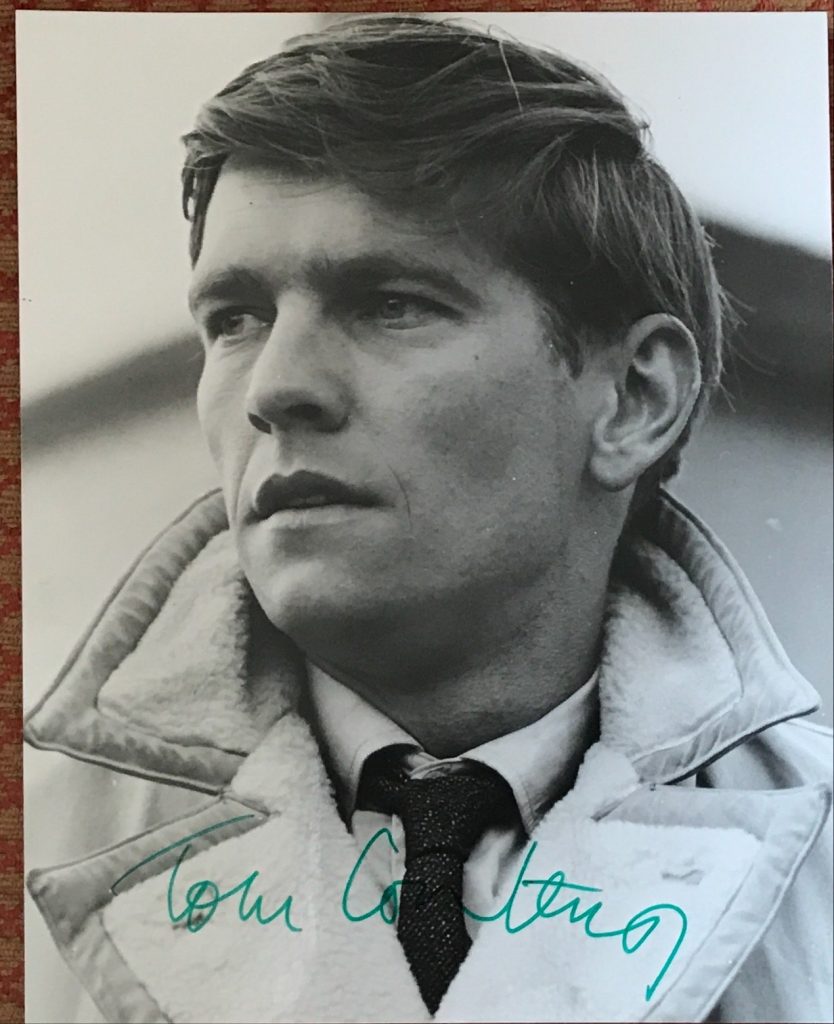

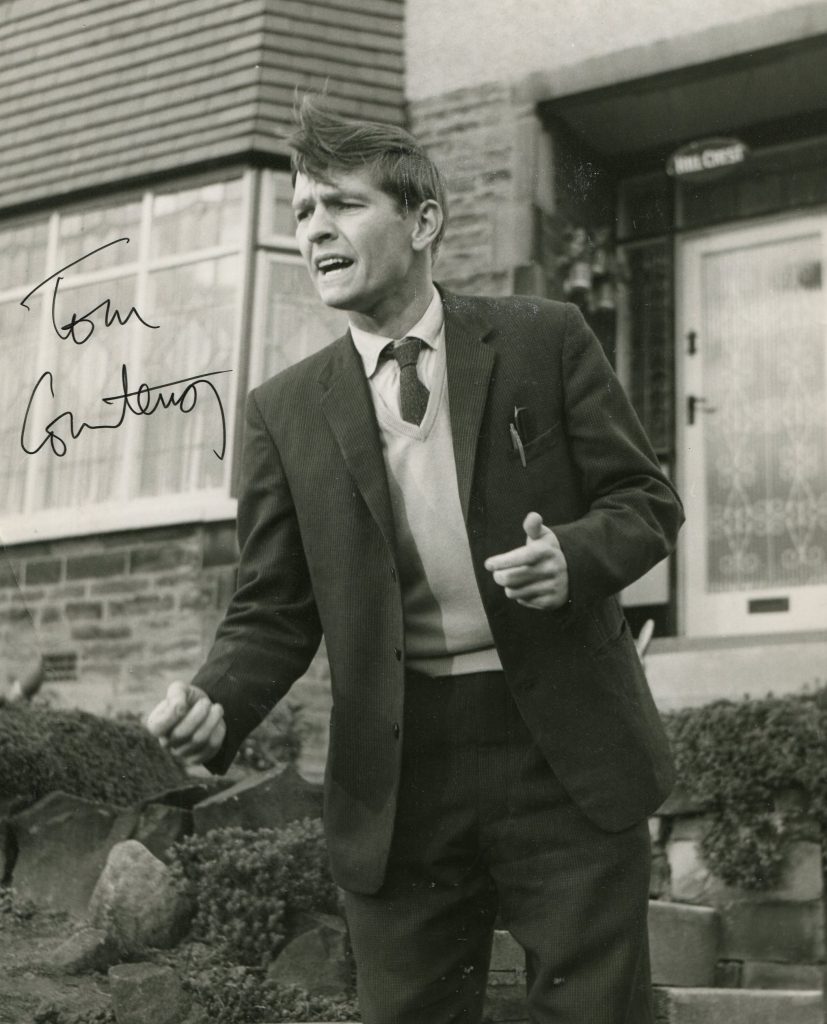

Daniel Massey was born in 1933 in London. He was the son of actors Adrianne Allen and Raymond Massey. He made his film debut in 1942 in “In Which We Serve”. His other films include “Mary, Queen of Scots”, “The Cat and the Canary” and “Vault of Horror”. His best remembered film role was in “Star” where he played Noel Coward. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance. Daniel Massey died in 1998 at the age of 64.

“Independent” obituary:

The son of the famous Canadian actor Raymond Massey and the actress Adrienne Allen, and the godson of Noel Coward, he was born in London in 1933 and educated at Eton and King’s College, Cambridge (where he acted with the university’s Footlights Club). After two years in the Scots Guards he decided to follow in his parents’ footsteps, appearing at the Connaught Theatre, Worthing, in Agatha Christie’s Peril at End House. He made his London debut at the Cambridge Theatre in 1957 with an outstanding performance as a gauche young American aristocrat in The Happiest Millionaire, a delightful comic portrayal which earned the cheers of first-nighters and rave reviews.

The same year, he made his adult screen debut (as a boy he had had a role in Coward’s In Which We Serve) in Girls at Sea and the following year he displayed his song and dance ability in the revue Living for Pleasure starring Dora Bryan (who named her oldest child, adopted during the run, after him). One of the show’s highlights was Massey’s smooth rendition with Janie Marden of the Richard Addinsell/Arthur Macrae duet “Love You Good, Love You Right”, and it led to the starring role in the Wolf Mankowitz musical Make Me An Offer (1959). With a stylishly witty performance as Charles Surface in John Gielgud’s revival of The School for Scandal at the Haymarket in 1962, Massey demonstrated his versatility, and throughout his career would prove equally adept in musicals, dramas, comedies and classics.

In 1963 in New York he created the role of Georg, the young salesman conducting a pen-pal romance with, unknowingly, his own shop assistant colleague (Barbara Cook), in the musical She Loves Me, now regarded a classic though it initially ran for only nine months. “When we came to the last performance,” said Massey later, “I cried right through the show . . . perhaps because it is so rare in one’s work that one can persuade oneself you say, ‘Hey, that was good.’ “

He returned to London to play Mark Antony in Julius Caesar (1964) at the Royal Court, then starred in Neil Simon’s comedy Barefoot in the Park (1965), as Captain Absolute in The Rivals (1966) and Jack Worthing in The Importance of Being Earnest (1967).

He returned to musicals with Popkiss (1972) in London and a stage version of the film Gigi (1973) in New York, though neither was a great success. Sporadic film appearances included The Entertainer (1960) and Moll Flanders (1965), and in 1968 his performance as his own godfather Noel Coward in Star!, the film biography of Gertrude Lawrence, was indisputably the best thing about the film, winning him a Golden Globe Award as Best Supporting Actor, plus an Oscar nomination. Coward himself wrote after seeing it,

Daniel Massey was excellent as me and had the sense to give an impression of me rather than try to imitate me. He was tactless enough to sing better than I do, but of course without my special matchless charm!

In fact, Massey both sang well and purveyed a lot of charm, and had the film been more successful it might have led to more prolific screen work. Instead, he concentrated on the theatre where his Lytton Strachey in Peter Luke’s Bloomsbury (1974), and Othello in Birmingham (1976) and a memorable Rosmer in Rosmersholm (1977) found him successfully tackling weightier roles. Joining the National Theatre, he played in The Philanderer (1979), The Hypochondriac (1981) and won the Swet award as Best Actor for his John Tanner in Shaw’s Man and Superman (1981). Two seasons with the Royal Shakespeare Company (1983-84) included works by Shakespeare, Saroyan (The Time of Your Life) and Granville Barker (Waste). “The Shaws, the Shakespeares and the Chekhovs are meat and drink to me,” Massey stated. “It’s the ambiguities in roles that are so important.” In 1987 he played the tortured hero Ben in the London production of Follies, introducing a new song written for the character by Stephen Sondheim, “Make the Most of Your Music”.

Massey’s own private life had its share of anguish. His parents divorced when he was six, and his mother, a noted beauty and a major star, gave glittering parties but was cold to him. Massey later described her as “an evil woman, a psychopath”, comparing her emotionally with Myra Hindley; such criticism totally estranged him from his actress sister Anna. (“It’s not Anna’s, it’s my problem,” he would admit.) Massey did not see his mother for the last 10 years of her life and did not go to her funeral.

In the mid-Fifties he married the actress Adrienne Corri (his mother refused to attend the wedding). “We were agonisingly incompatible but we had an extraordinary physical attraction,” he stated. The tempestuous marriage ended in 1968, and after another relationship which produced a son, Paul, he married the actress Penelope Wilton, with whom he had a daughter Alice. After his divorce from Wilton, he formed a relationship with her younger sister Lindy in 1984, the same year he started an ultimately successful course of psycho-therapy to combat acute depression. Later he and Lindy married, but in 1992 Massey was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease. With typical wit and charm he joked about it: “If you’ve got to have a serious illness, that’s the one to get, because it’s get-at- able”. And he successfully fought it off with chemotherapy, returning to the stage with an acclaimed performance as Wilhelm Furtwangler, the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic during the Third Reich, in Ronald Harwood’s Taking Sides (1995), which raised the question of the ambivalent conductor’s motives in playing for Hitler’s regime.

After the London run, Massey want to Broadway with the play, for what was sadly to be his last theatrical triumph.

Daniel Raymond Massey, actor: born London 19 October 1933; married first Adrienne Corri (marriage dissolved 1968), (one son), second Penelope Wilton (one daughter; marriage dissolved), third Lindy Wilton (two stepdaughters); died London 25 March 1998.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.