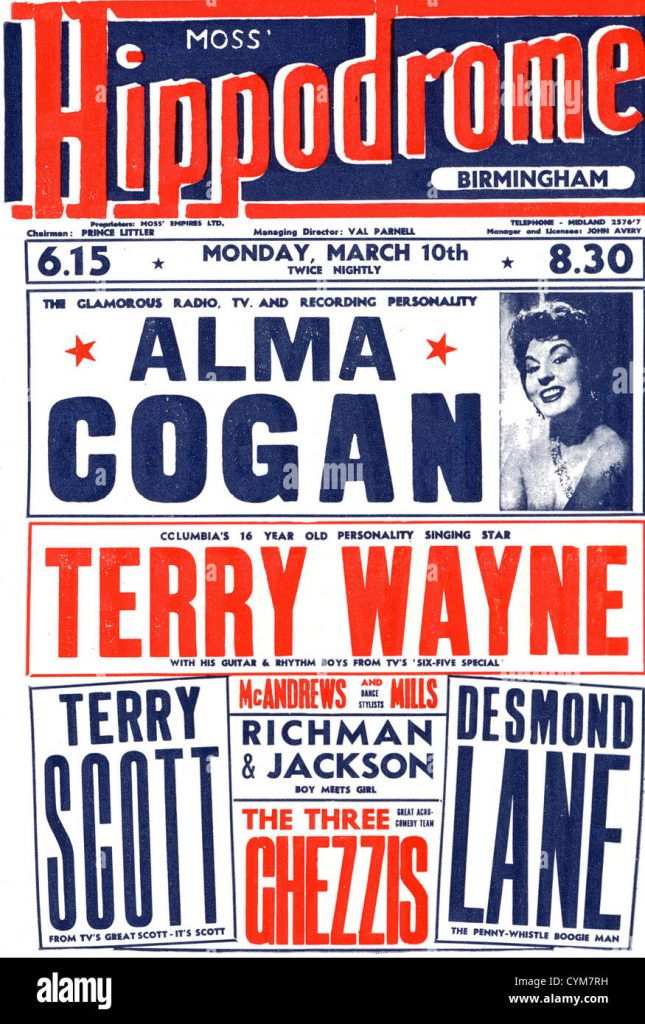

Alma Cogan was one of the most popular singers in Britain in the early to mid 1950’s with a string of Top Ten hits to her credit. She did too have make a number of films in the UK. She was born in 1932 in London. Among her films were “Dance Hall” in 1950 and “For Better, For Worse” in 1954. Alma Cogan died in 1966 aged only 34.

“MailOnline” article by Michael Thornton in 2006:

By MICHAEL THORNTON

Alma Cogan was the first female pop star – yet was dead by 34. For years, there were cruel whispers about her sexuality. But now her sister reveals she was John Lennon’s lover:

Late on an October night, 40 years ago last month, in a private room at London’s Middlesex Hospital, one of the most famous women in Britain lay in a coma as her young life slowly ebbed away. Her face, once so alive and radiant with health and vitality, had been instantly recognisable for 12 years to millions of television viewers and record fans.

But as cancer had spread inexorably through her body, she had lost so much weight that she now appeared almost skeletal. One of her closest friends, visiting her during her final days, was so devastated by her appearance that he rushed weeping from the room into the street.

When, on October 26, 1966, giant headlines across the front of newspapers informed a shocked public that Alma Cogan, Britain’s greatest female recording star of the Fifties and early Sixties, had died from cancer at the tragically young age of 34, there was universal grief and incredulity.

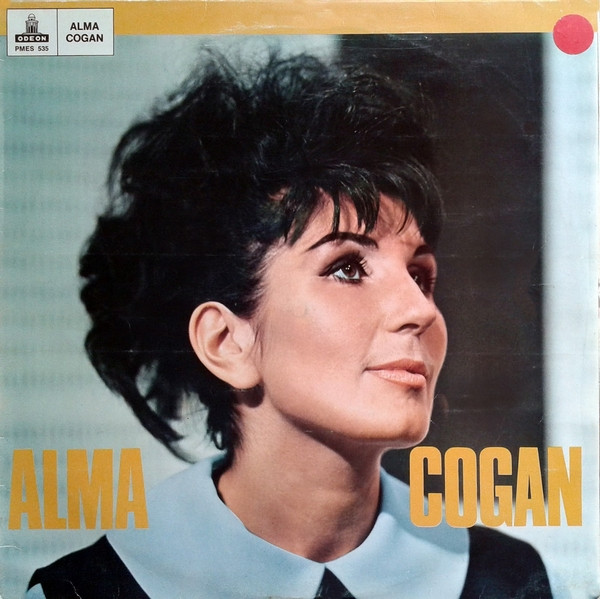

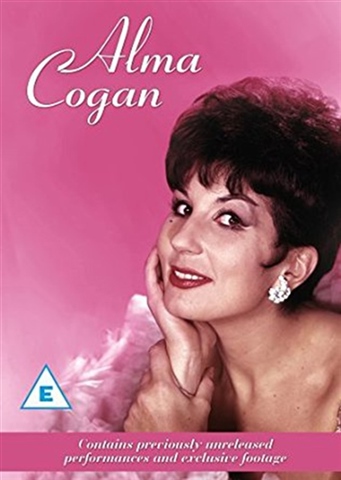

It just didn’t seem possible that the bouncy, bright and bubbling Alma, with her sequinned, voluminous dresses, brunette beehive, sparkling eyes and wide, dynamic smile, could be snuffed out of existence with such shocking suddenness at so early an age.

During her life, Alma’s brio and talent had brought her extraordinary fame – but with it came unwelcome attention. There were questions about her sexuality and rumours of a secret affair with John Lennon which was conducted under his wife Cynthia’s nose.

But what no one could have predicted when she died was that today, four decades on, Alma would still be creating controversy. Years after her death, she caused her immediate family to feel that they were being ‘stalked’ and haunted by disciples of her legend. And then she was publicly – and preposterously – linked to Myra Hindley.

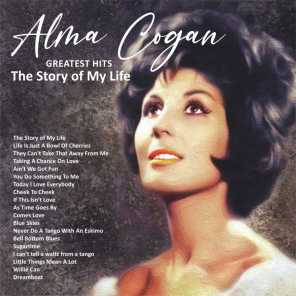

In a brief but meteoric career, Alma packed theatres all over the country, dazzled millions of TV viewers with her exuberant Jewish chutzpah, and clocked up 20 hit records, more than any other British female singer, spending an astonishing total of 109 weeks in the charts. As she belted out one novelty hit after another – Bell Bottom Blues, Dreamboat, I Can’t Tell A Waltz From A Tango, Twenty Tiny Fingers, Never Do A Tango With An Eskimo, Cowboy Jimmy Joe, and Just Couldn’t Resistor – her style was the very quintessence of kitschand the height of high camp.

A BBC television documentary to be screened on Friday and a DVD just released to mark the 40th anniversary of her death present Cogan as a sexual enigma. Two of the men who regularly escorted her, composer Lionel Bart and Beatles manager Brian Epstein, were both gay. And one of Cogan’s closest friends, the broadcaster David Jacobs, says: ‘I always thought of her as a virgin.’

One story, allegedly told by the young Dusty Springfield, an admitted lesbian herself, with whom Cogan was said to be closely involved, was that Alma was not really gay, but had been raped as a young teenager and had developed a mental block about sex with men as a consequence.

Her younger sister, West End stage star Sandra Caron, who is also Alma’s biographer, dismisses this rape story, saying: ‘People just make these things up.’ But Sandra, some years Alma’s junior, would have been a small child at the time and might well not have been told about the rape, if it happened.

One more dramatic twist in the mystery of Cogan and sex is the clandestine love affair between Alma and John Lennon.

Sandra Caron, who knew the Beatles even earlier than Alma and became very close to Paul McCartney, breaks her silence on this story for the first time.

She told me: ‘I knew about Alma and John, of course, but it was something no one admitted because John was married. We had a very strict Jewish upbringing and my mother would never have approved of a relationship between Alma and a married man.’

Ironically, before The Beatles rose to fame, Cogan represented everything Lennon most disliked. As a student at the Liverpool College of Art, Lennon ‘used to make horrible jokes against the singer Alma Cogan, impersonating her singing: “Sugar In The Morning, Sugar In The Evening, Sugar At Suppertime.” He’d pull crazy expressions on his face to try to imitate her.’

But in 1962, when The Beatles appeared with Cogan in Sunday Night At The London Palladium, it was obvious that Lennon rapidly revised his view. ‘John was potty about her,’ George Harrison revealed later. ‘He thought her really sexy and was gutted when she died.’ After the Fab Four’s first visit to Alma’s home in Stafford Court, Kensington High Street, where she lived with her widowed mother, Fay, and her younger sister, Sandra, Lennon gave Cogan the name ‘Sara Sequin’, while Fay became ‘Ma McCogie’. The Cogan flat was probably the most celebrated showbusiness salon in London history. Princess Margaret, Audrey Hepburn, Cary Grant, Sir Noel Coward, Ethel Merman, Danny Kaye and Sammy Davis Jr were all regular visitors. Of her first visit to Stafford Court, Lennon’s first wife, Cynthia, records: ‘John and I had thought of her as out-of-date and unhip. We remembered her in the oldfashioned cinched-in waists and wide skirts of the Fifties.

But in the flesh she was beautiful, intelligent and funny, oozing sex appeal and charm. Walking into her home for the first time was like walking into another world. ‘It was decorated like a swish nightclub with dark, richly coloured silken fabrics and brocades everywhere. Every surface was covered with ethnic sculptures, ornaments and dozens of photographs in elaborate silver, gold and jewelled frames.’

Cynthia became convinced that Alma and John were lovers. ‘I could see the sexual tension between them,’ she recalled, ‘and how outrageously she flirted with him. But I had no real grounds for suspicion…just a strong gut feeling.’ Her suspicions were correct. Alma and Lennon, both heavily disguised, took to meeting for passionate interludes in anonymous West End hotel suites, where they sometimes registered as ‘Mr and Mrs Winston’ (Lennon’s middle name). The Beatles became regular visitors to the Cogan residence. It was on Alma’s piano, with Sandra at his side, that Paul McCartney composed Yesterday. It was 3am and McCartney first called the tune Scrambled Eggs because that’s what ‘Ma McCogie’ had just cooked them.

.’

This article can also be accessed on “MailOnline” here.

As the emergence of The Beatles and of younger female singers – such as Lulu, Sandie Shaw and Dusty Springfield – revolutionised the pop music scene, Cogan’s records ceased to become hits and her star dimmed in Britain, though not internationally. In Japan, her recording of Just Couldn’t Resist Her With Her Pocket Transistor topped the charts for an unprecedented ten months. Andrew Loog Oldham, the manager of the Rolling Stones, also thought Alma ‘very sexy…we all fancied her’. He considered her later recordings ‘naff’, but noted Lennon’s anxiety to help Cogan recover a foothold in the charts.

Alma’s pianist, Stan Foster, who accompanied her on world tours, allegedly had a sexual relationship with her, but he says: ‘She was Jewish and I wasn’t. Her family wouldn’t have approved of that. I’m sure they didn’t.’ Unlike Lennon and Foster, the last man in her life was Jewish: Brian Morris, who managed the Ad Lib, one of London’s trendiest nightclubs.

He was desperate to marry her, and Sandra Caron says: ‘They were engaged. It was absolutely serious.’ But no engagement was ever announced, and some of her friends still believe that he was much more in love with her than she was with him.’ Whatever the truth, it was now academic. She had started to lose weight. ‘Alma had these weight-losing injections,’ the singer Anne Shelton told the music critic Chris White. ‘At the time, they were highly experimental and quite controversial. She certainly lost the weight, but after those injections, she was never well again.’

hortly afterwards, ovarian cancer was diagnosed, but no one seems certain now whether she knew this or not. Her photographer cousin Howard Grey took a last colour closeup of her with her arms around Brian Morris’s neck, and caught a look of almost unearthly beauty. Was it because her time was short? Or had she, at long last, found the love that had so long eluded her? Sandra Caron, who had scored a major success herself as a performer in the United States, was in New York, preparing to appear on the Merv Griffin Show, when Alma’s condition suddenly deteriorated. Sandra cancelled her appearance and flew back to London.

On the morning after her death, shocked radio listeners switched on to hear Cogan’s voice singing an Irving Berlin number, opening with the words: ‘Heaven, I’m in Heaven.’ At the funeral, attended by almost every star in show business, a distraught Brian Morris had to be restrained from throwing himself into Alma’s grave.

Two weeks after Cogan died, Lennon met Yoko Ono, the woman who was to control and dominate the rest of his life, until he too, like Alma, came to an untimely end at the age of 40, from an assassin’s bullet. The fallout from Cogan’s tragically early death was destined to cast a long shadow over the life and career of her younger sister, Sandra Caron. Now in her 60s, and happily married to the American stage and screen actor Brian Greene, Sandra is an actress of skill and distinction.

Merryn Threadgould’s elegiac and moving BBC documentary provides us with an answer: ‘Alma Cogan,’ it concludes, ‘seemed to wear life lightly. Maybe that’s why her early death remains so shocking, a denial of the optimism she represented. Yet it’s that optimism which has become her legacy. She still gives people reasons to be cheerful