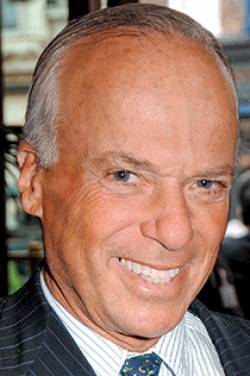

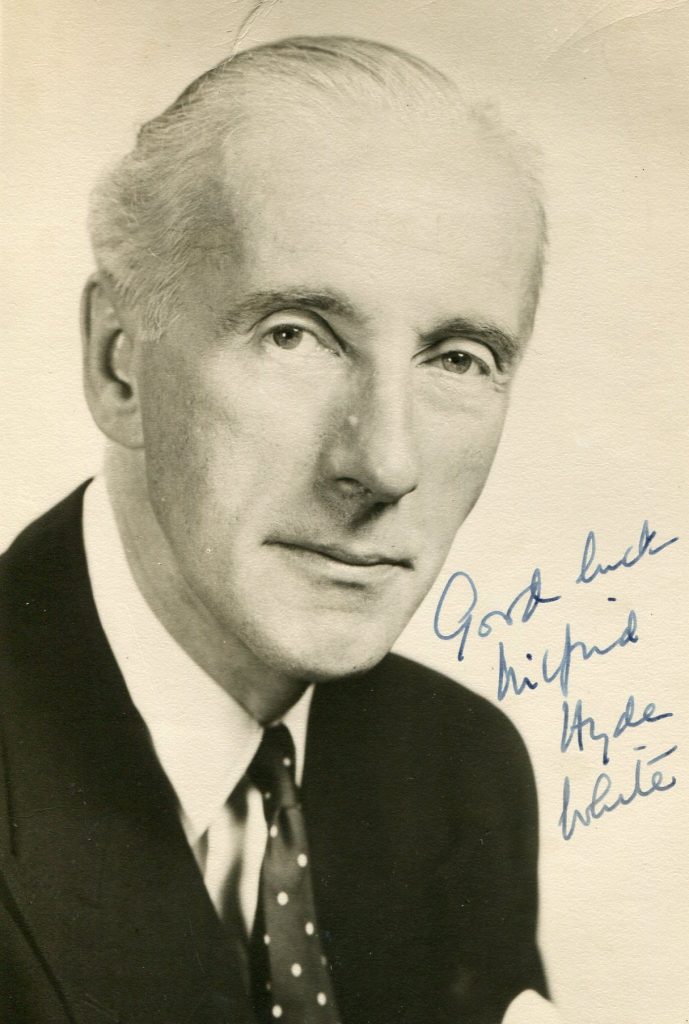

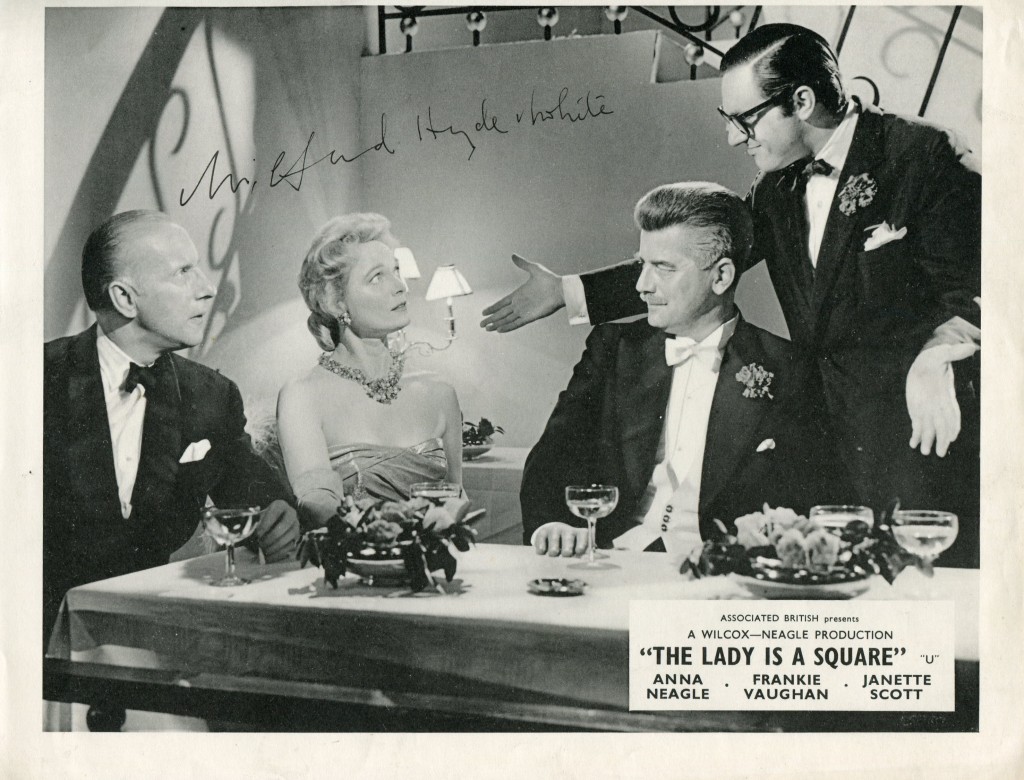

Wilfrid Hyde-White came to prominence in late middle age, after having spent a long time in minor roles. He was born in 1903 in Burton-on-the-Water, England, the son of a rector. He made his film debut in 1934 in “Josser on the Farm” and then went on to make “Turned Out Nice Again” with George Formby.

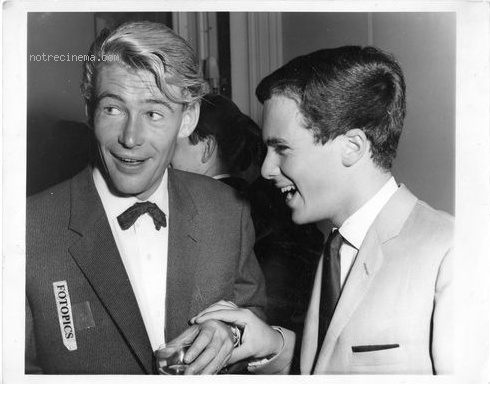

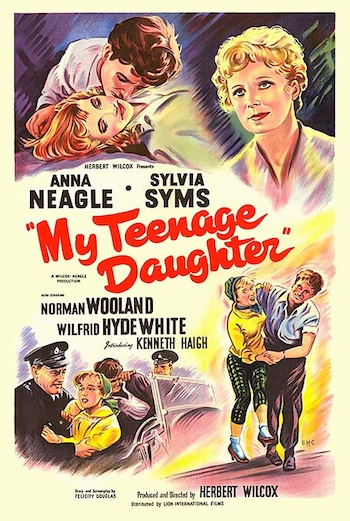

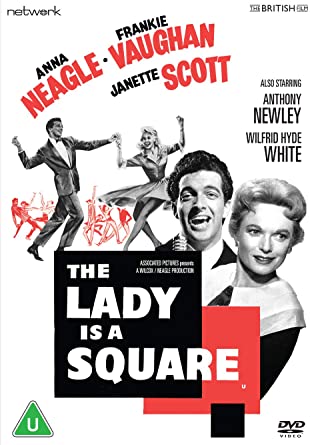

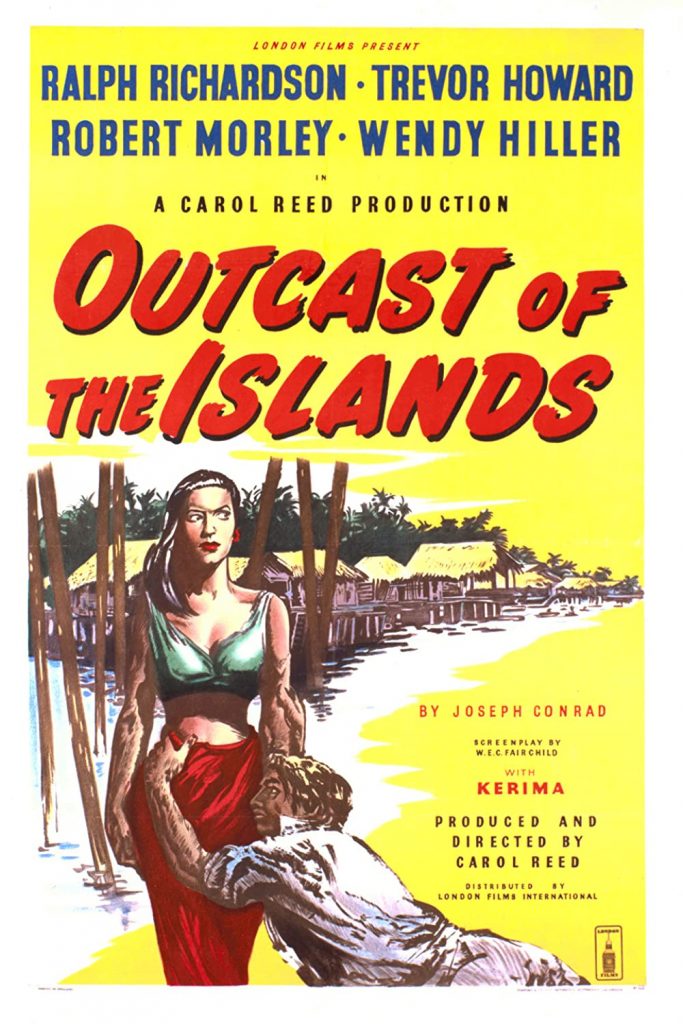

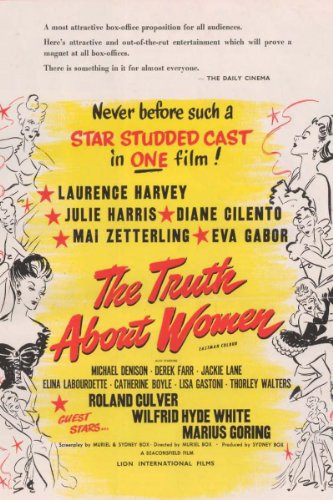

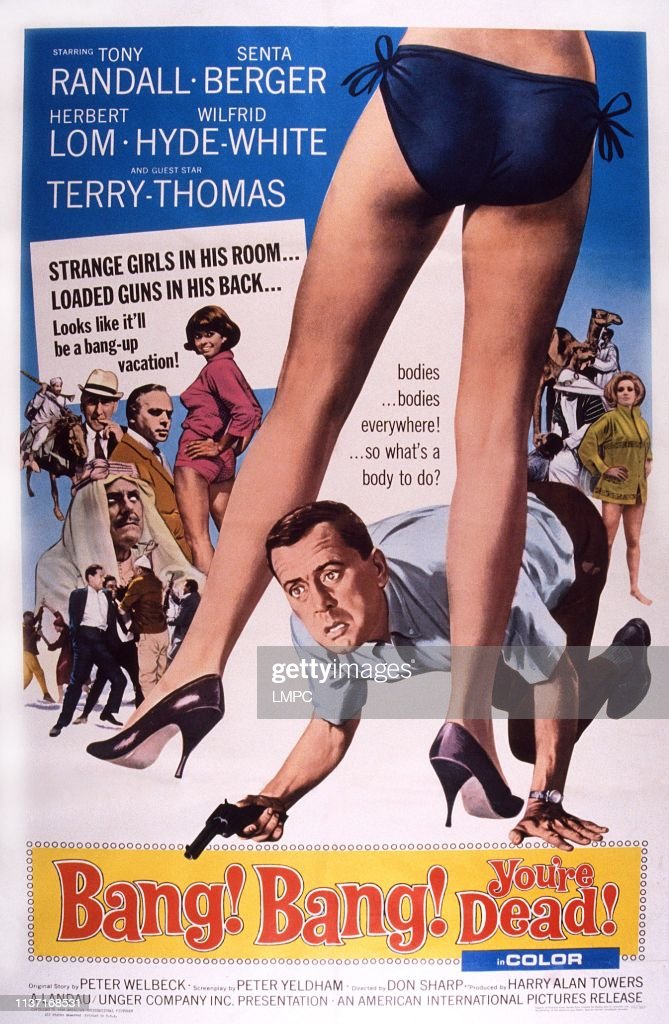

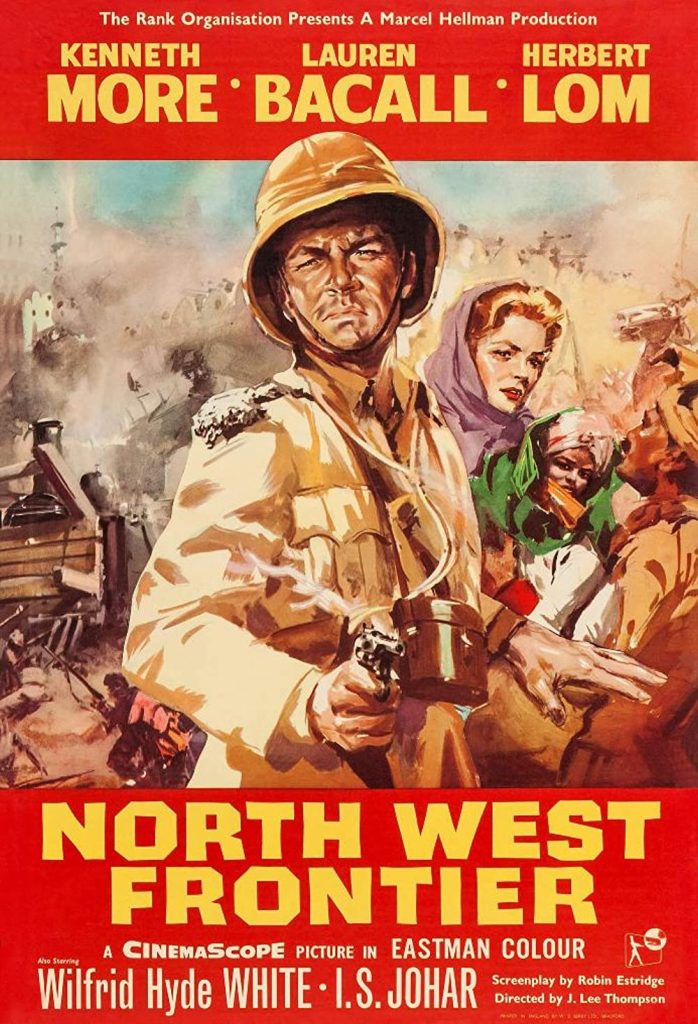

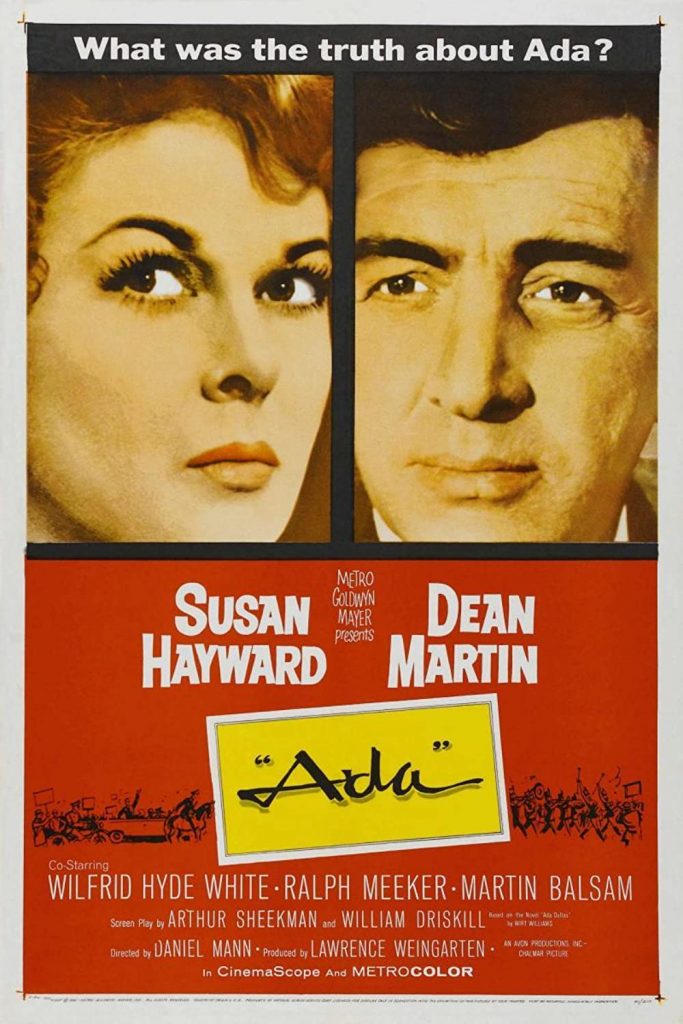

His breakthrough role came in the Carol Reed classic of 1949 “The Third Man”. “North West Frontier” with Kenneth More and Lauren Bacall weas a major success. He went to Hollywood in 1959 and made such films as “Ada” with Susan Hayward, “let’s Make Love” with Marilyn Monroe and as Pickering in “My Fair Lady” in 1964. Most of his subsequent career was spent in Hollywood where he died in 1991 at the age of 87. His son is the actor Alex Hyde-White.

IMDB Entry:

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Jim Beaver <jumblejim@prodigy.net>

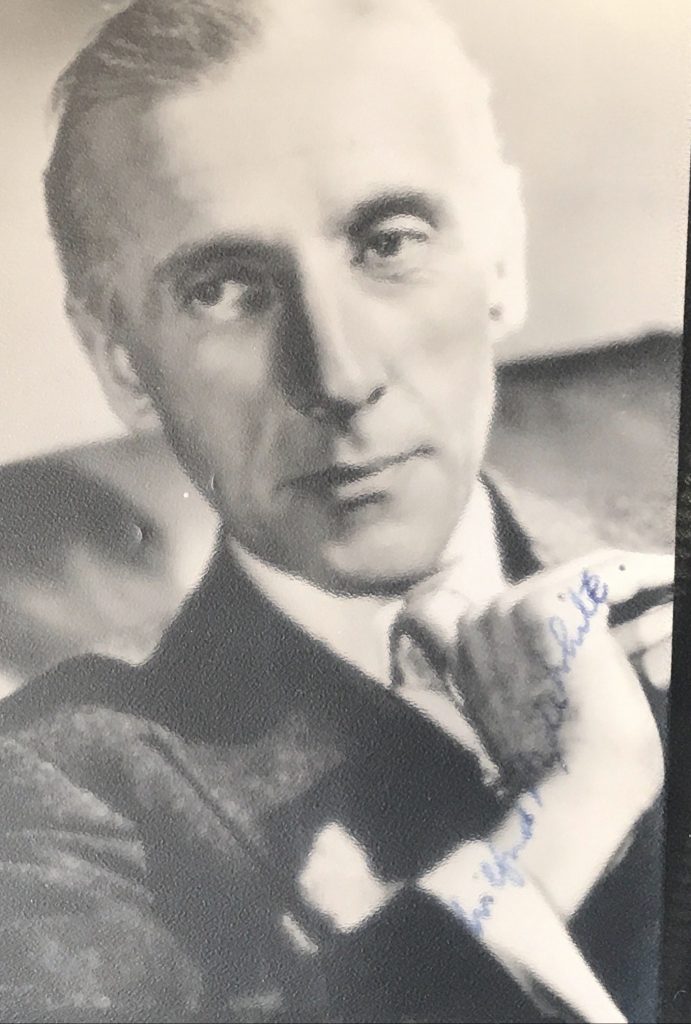

British character actor of wry charm, equally at home in amused or strait-laced characters. A native of Bourton-on-the-Water in Gloucestershire, he attended Marlborough College and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. His stage debut came in 1922, and by 1925 he was a busy London actor. He married actress Blanche Glynne (real name: Blanche Hope Aitken) and in 1932 toured South Africa in plays. Alleged to have been spotted by George Cukor during a performance in Aldritch, Hyde-White (with or without Cukor’s help) made his film debut in 1934.

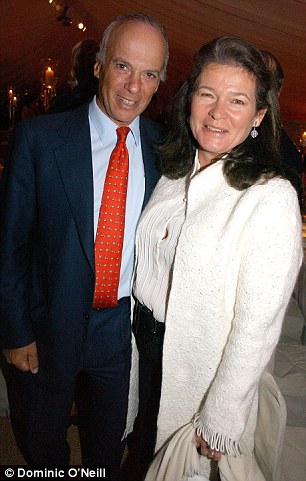

He often appeared under the name Hyde White in these early films. He continued to act upon the stage, playing oppositeLaurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in “Caesar and Cleopatra” and “Antony and Cleopatra” in 1951. With scores of films to his credit, he will always be remembered for one, My Fair Lady (1964), in which he played Colonel Pickering. Active into his ninth decade, Hyde-White died six days before his 88th birthday. He was survived by his second wife, Ethel, and three children.

His IMDB entry can also be accessed here.

TCM overview:

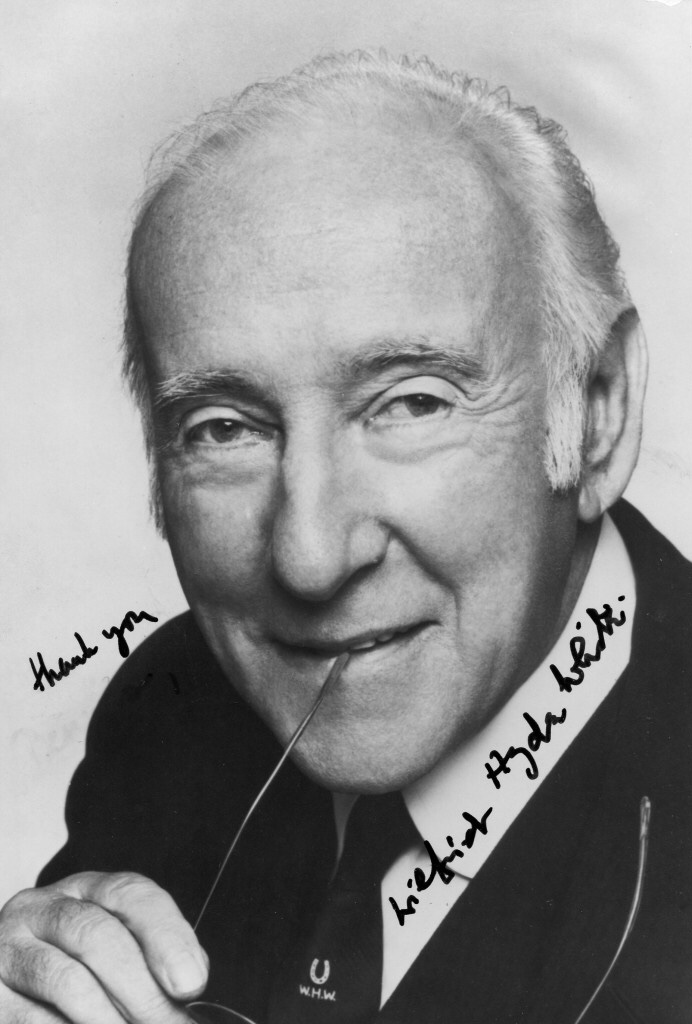

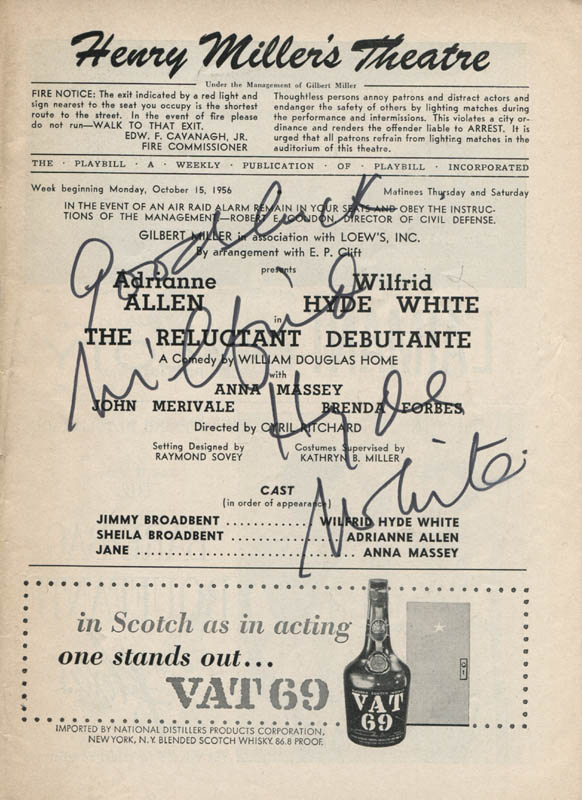

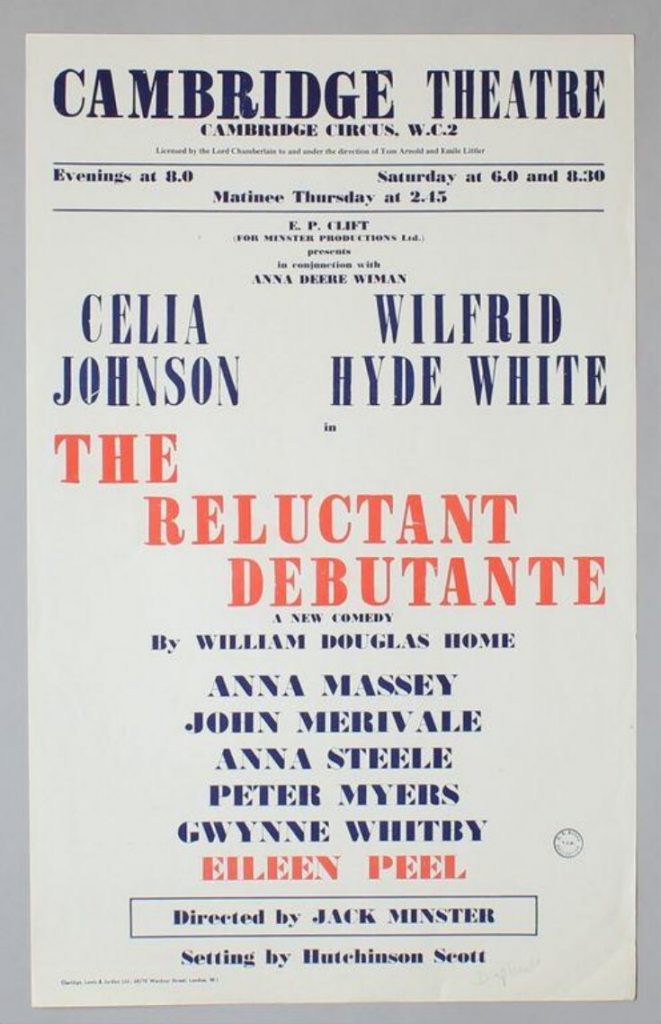

Distinguished-looking, urbane character actor noted for his droll humor on stage as the father of the title character in the drawing room comedy “The Reluctant Debutante” (London 1956, Broadway 1957) and the Laurence Olivier-Vivien Leigh “Caesar and Cleopatra” (1952).

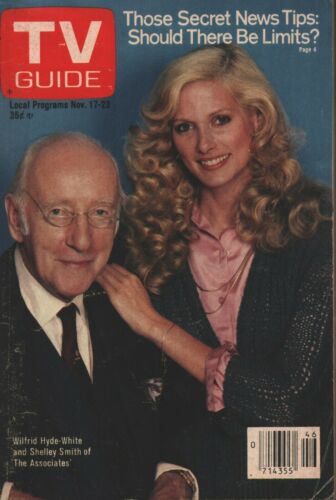

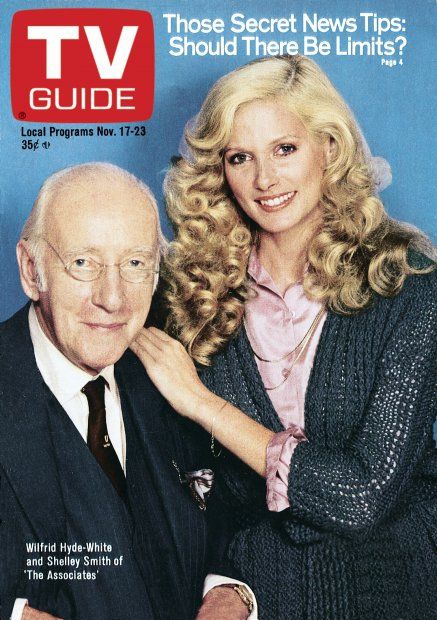

Often cast as genteel Englishmen whose surface manners mask a roguish or larcenous soul, Hyde-White is best known for his performances as Crippin, a British Council functionary in “The Third Man” (1949), the hypocritical headmaster in “The Browning Version” (1951) and Henry Higgins’s bemused friend, Colonel Pickering, in “My Fair Lady” (1964). On TV he appeared briefly on the nighttime soap opera “Peyton Place” (1967), starred as Emerson Marshall in the legal comedy series, “The Associates” (1979) and played Dr. Goodfellow in “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century” (1981).

A supremely unctuous character player, adept at smoothly honed sycophancy – as, for example, the literary chairman of The Third Man (d. Carol Reed, 1949), the headmaster in The Browning Version (d. Anthony Asquith, 1951), and one of the wealthy brothers in The Million Pound Note (d. Ronald Neame, 1953).

With his plummy tones and sleekly coiffed appearance, he usually played upper-class, but there is a smattering of fake smoothies, like crim Soapie Stevens in Two-Way Stretch (d. Robert Day, 1960), or the merely deferential like the jeweller in Bond Street (d. Gordon Parry, 1948). However, it is hopeless trying to limit the highlights in such a career, which spanned fifty years, every type of British film and not a few international ones, most famously as that arch-gent, Colonel Pickering, in My Fair Lady (US, d. George Cukor, 1964).

Marlborough-educated and RADA-trained, he was first on stage in 1922, scoring a major hit as the father of The Reluctant Debutante (1955) and screen since 1936. His son Alex Hyde-White (b.London, 1959) has acted in several films including Biggles (d. John Hough, 1986) and Pretty Woman(US, d. Garry Marshall, 1990).

Brian McFarlane, Encyclopedia of British Film

New York Times obituary in 1991:

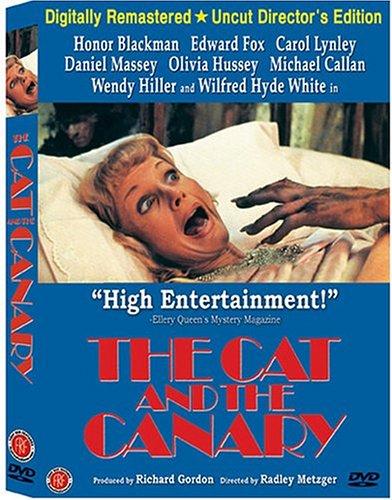

Wilfrid Hyde-White, the English actor who appeared in films including “My Fair Lady,” “Ten Little Indians,” “The Third Man” and “The Browning Version,” died yesterday in Woodland Hills, Calif. He was 87 years old.

He died of congestive heart failure at the Motion Picture and Television Hospital, where he had been a patient since 1985, said Louella Benson, a spokeswoman for the Motion Picture and Television Fund.

Mr. Hyde-White was especially well known for his urbane drollery, in such roles as the father of the title character in the play “The Reluctant Debutante,” which he performed in London and then, in 1956 and 1957, on Broadway.

Reviewing that drawing-room comedy, Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times said Mr. Hyde White gave a “brilliant performance” as the head of a frantic household — “relaxed, quizzical, neat, funny.” Of ‘Certain Tricks’

The actor told an interviewer at the time: “The premise of the drollery has to be firm. It is allowed to look leisurely, but actually my technique is hidebound by method. I really don’t take chances onstage. My style of acting is made up of certain tricks acquired over many years.”

Those, he said, included lowering his voice if audiences were noisy or sleepy. The worst thing to do is outshout them, he said, and if they are sleeping, do not awaken them, thereby eliminating a few critics.

“The suaveness,” he said, “isn’t born of confidence: it’s born of fright.” Comedies on the Stage

Mr. Hyde-White, who was born in Gloucester, began his career in a series of comedies produced during the late 1920’s at the Aldwych Theater in London, then began his film career as a stuffy burgomaster in “Rembrandt.”

He played a professor in “The Third Man” (1950) and the headmaster in “The Browning Version,” the 1951 film based on Terence Rattigan’s play. In “My Fair Lady” (1964), he played Henry Higgins’s associate.

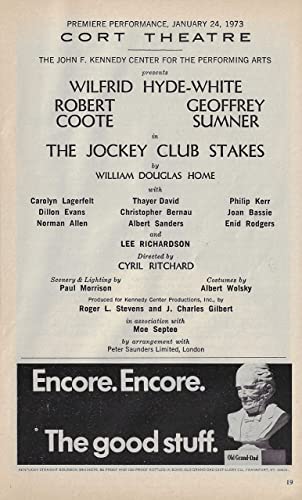

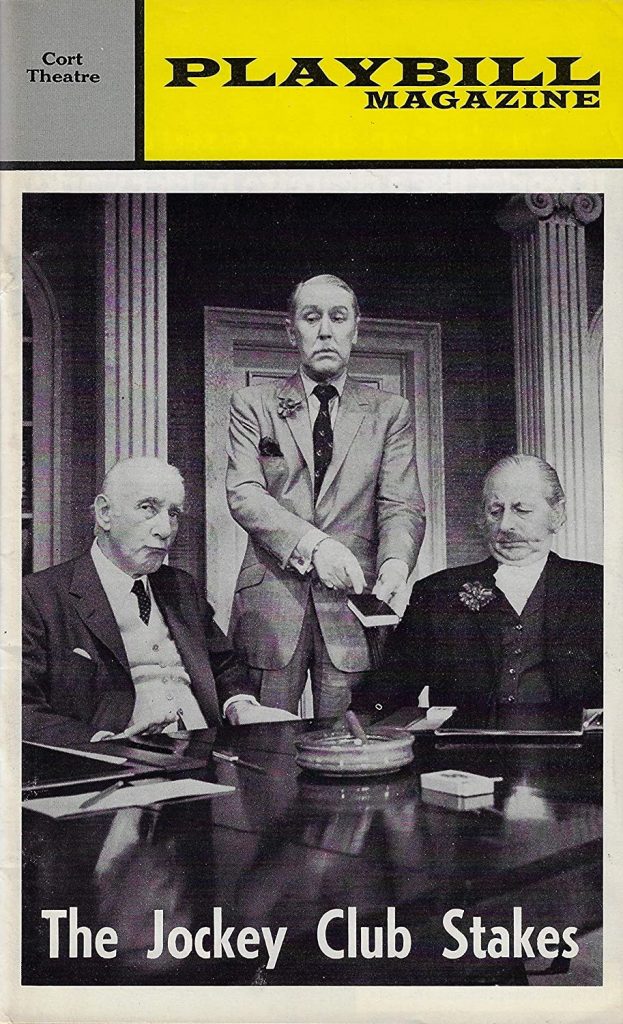

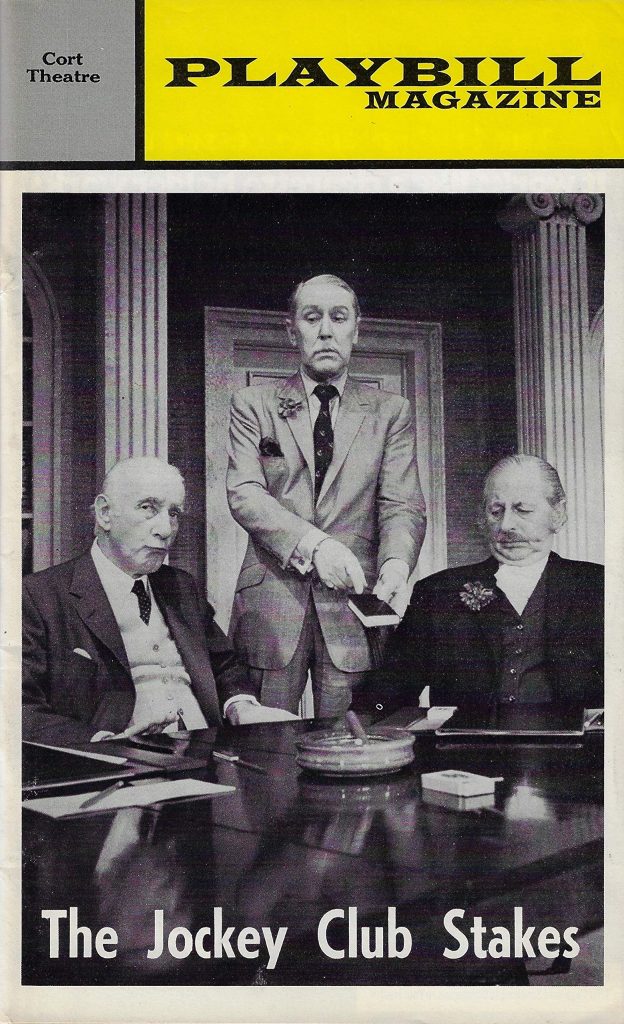

In 1952, he appeared in New York with Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in “Caesar and Cleopoatra” and “Antony and Cleopatra.” In 1973, he played an urbane marquis on Broadway in “The Jockey Club Stakes,” a British comedy.

His American television credits included a brief run in the 1960’s nighttime soap opera “Peyton Place.” He also starred as Emerson Marshall in ABC’s lawyer comedy series “The Associates” and appeared as Dr. Goodfellow in “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.”

He is survived by his wife, Ethel; two sons, Alex and Michael; a daughter, Juliet, and four grandsons