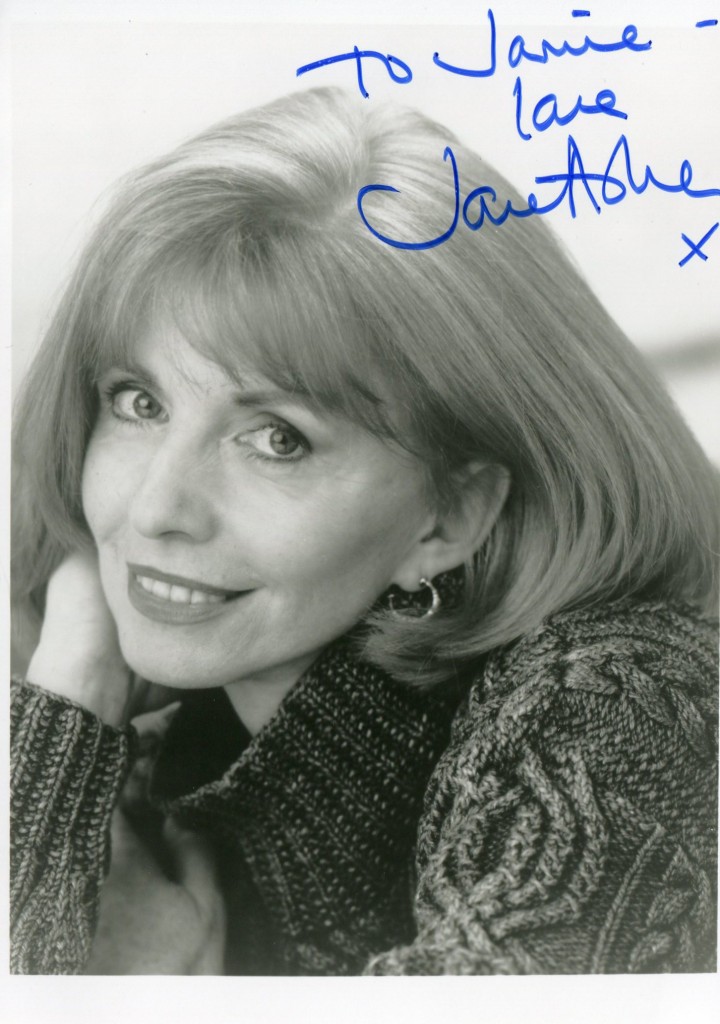

That there is a darker side to her, yearning for expression, is something that leaked out in the last couple of years with the publication of her two novels, The Longing and The Question. Both deal with uncomfortable subjects – infertility, adultery, sexual jealousy, stalking, obsession, revenge, the edge of madness, the borders of life and death – and confront them head-on with a nagging determination to understand why things go terribly wrong. They’re a far cry from Silent Nights for You and Your Baby (1984), Jane Asher’s Book of Cake Decorating Ideas (1993) and the dozen more or so fluffy titles in her Who’s Who entry. They’ve also brought Ms Asher a new career at fifty, as a celebrity and writer who refuses to become – and shouldn’t be confused with – a “celebrity novelist”.

When you meet her, you aren’t struck by her saintliness or her maternal qualities. She turns up, breathless and fantastically friendly, in the Conrad Hotel in Chelsea Harbour, wearing blue denim jeans and a canary yellow sweater, and talks with animation and frankness about every subject bar one. (“If you don’t mind my asking, did you like Linda McCartney?” “I do mind you asking” – and her mouth clanged shut like a steel trap). She’s impressively well read, quoting Martin Amis, praising Ian McEwan and saying how reading Alain de Botton has turned her on to Proust, but wary of giving herself airs as The Writer.

The Question (HarperCollins), her latest novel, concerns a well-heeled, 58-year-old housewife called Eleanor, with a contented but childless and sexless marriage to a dull property speculator called John who squeezes nasty new homes into working-class housing estates and wears awful ties. They have a life of routine until Eleanor realises John is having an affair. Her investigations unearth the fact that her moth-eaten hubby has been harbouring a mistress and daughter under her nose for the best part of 20 years. No sooner has Eleanor embarked on revenge than John meets with a nasty accident upon which his wife, mistress and daughter negotiate for possession of his stricken form.

“I always found it fascinating that you could live with somebody for years and not know a giant chunk of their life,” she says. “To find the life you’d thought you lived was completely unreal and not what you thought it was. That was my launch pad. And also to explore jealousy, especially sexual jealousy in a woman who thought that sex was no longer part of her life.” Ms Asher’s explanatory mode of narrative (in which the tiniest fugitive sensations are minutely explored and dissected) is lit up in such moments by alarming castration fantasies and private sexual frenzies, as Eleanor, having stumbled on the plot of her husband’s real life, threatens to lose her own in spectacular fashion.

Eleanor is not, it’s fair to say, an autobiographical creation. “She is a snobbish cow,” agrees her creator, “but I feel sympathetic to her because she thought she had a nice ordered life and it’s exploded. And though nobody’s asked me yet if Gerald [Scarfe] has been concealing a second family, I expect someone will.”

Is it too pat, I wonder, to see this study of domestic disintegration as a kind of externalised nightmare for someone whose life, like Ms Asher’s, seems so lucky, so full of support systems, so balanced, so perfect? “Yes it would,” she says shortly, “because it isn’t true. The problems and tragedies and pains and illnesses in one’s private life I, like most people, don’t talk about. You can appear sunny and smiley and your hair’s done and your make-up’s OK and that’s the side you show to the world. But it doesn’t mean that things are permanently wonderful. Compared to most people’s, I have an extremely privileged, happy life, but it doesn’t mean I don’t have the same horrors and worries and middle-of-the-night traumas, and that’s the part of me I write from. We’ve all peeped over the abyss, haven’t we?”

She has been asked a lot about the darkness of her subject-matter, “and a lot of it is just the contrast with the apparently fluffy mumsy cakey image. Sometimes I think it’s almost worth spending 20 years cultivating this image, so people expect a little lightweight romantic comedy, and you produce a book that’s a bit dark and startle them. We just float along pretending everything’s all right, but it isn’t. It’s ghastly for the majority of the planet. Just as you can see the world in a grain of sand, you can also see horror in a teacup.” “I will show you fear,” I quote, “in a handful of dust.” “Exactly,” says Ms Asher smartly, “and did I mention that TS Eliot was a relative of my mother’s? From her brief excursion to the gloomiest visionary depths, she seems suddenly restored.

I can’t tell you the question that’s asked at the climax of The Question, but it sets up a nastily tidy ending reminiscent of a Roald Dahl short story. “There was a cutting in the paper,” she explains, “a heartbreaking story about people who were considered to be in a persistent vegetative state, whom they suddenly started getting through to, using a buzzer. They found they could communicate with a chap who’d been like that for eight years. And I thought, what an extraordinary situation for people to be trapped in.”

We are in the neurophysiological territory of Oliver Sacks, the great Anglo-American cartographer of picturesquely wrecked minds. Ms Asher nods. “He was a student of my father’s, you know, at the Central Middlesex hospital. And so was Jonathan Miller.” Richard Asher, MD, FRCP, who died in 1968, clearly remains the apple of his daughter’s eye. “He used to bring home marvellous stories from the hospital to tell over the dinner table. He once took me to see the skull of the Elephant Man. And he bought me Tales from the London Hospital, full of marvellous grisly stories about `the blood on the brown rubber sheets’…”

Rather than flee from this rather grotesque entertainment, Jane nearly followed in her Dad’s footsteps. “I do think, if I hadn’t been acting from an early age, I’d have gone into medicine.” Instead, years later, her first novel dealt with a quasi-medical condition – Munchhausen’s syndrome, in which people pretend to suffer from medical problems in order to draw attention to themselves – which was first discovered by her father. “`Described’ is the word they use, I think, not `discover’, because people had known about it before but not pinned it down as a syndrome. My father was the first. And it’s absolutely typical of him that he didn’t call it Asher’s syndrome.”

There’s a posh side to Ms Asher, a cool aristocratic mien that’s expressed in the lift of her feline eyebrows and the set of her generous mouth. It comes from her mother, Margaret, a professor of music, who, along with the TS Eliot connection, is a cousin of Earl St Germans. “I had an upper-middle-class upbringing at home, I suppose,” says Jane, “though, of course, the edges have been rubbed off, partly by being a travelling player, rogue and vagabond. You move in a wonderfully classless world being an actress.” At Miss Lambert’s School in Paddington, London, she learnt a lot about manners. “It was a school for nice young ladies and was quite correct,” she says. “If we met the headmistress on the stairs, we had to bob a little curtsey. And we had to learn a Court curtsey just in case you met a Royal personage one day.” She demonstrates. With a Court curtsey, it seems, one knee must be tucked awkwardly behind one’s stiff leg, making the luckless courtier look like a cringing horse.

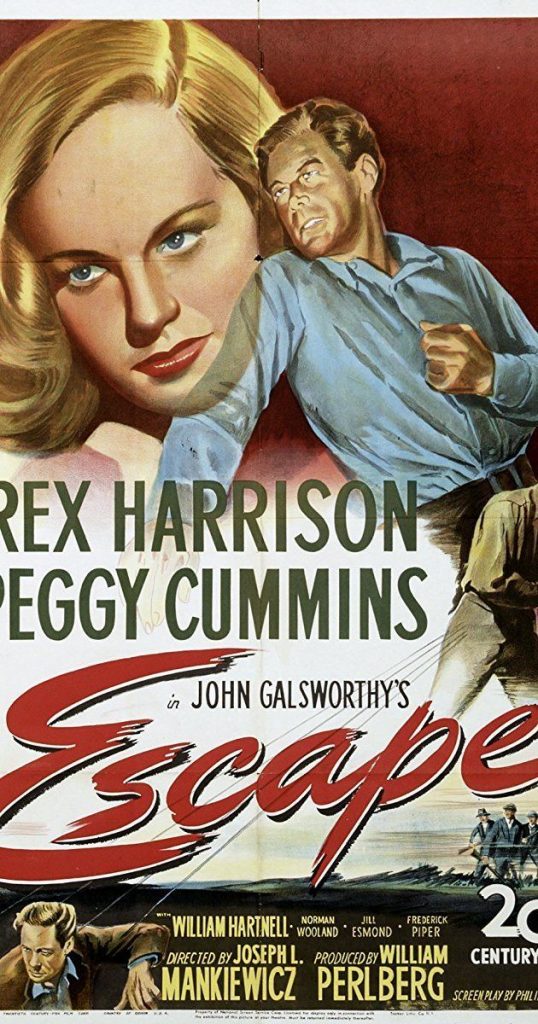

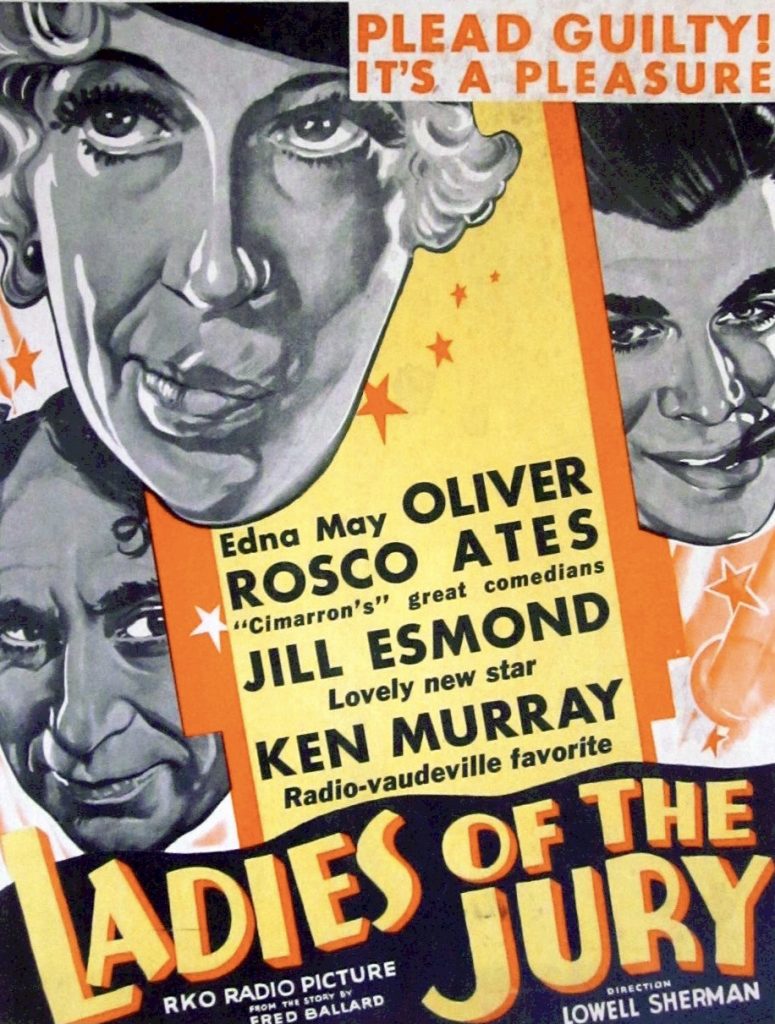

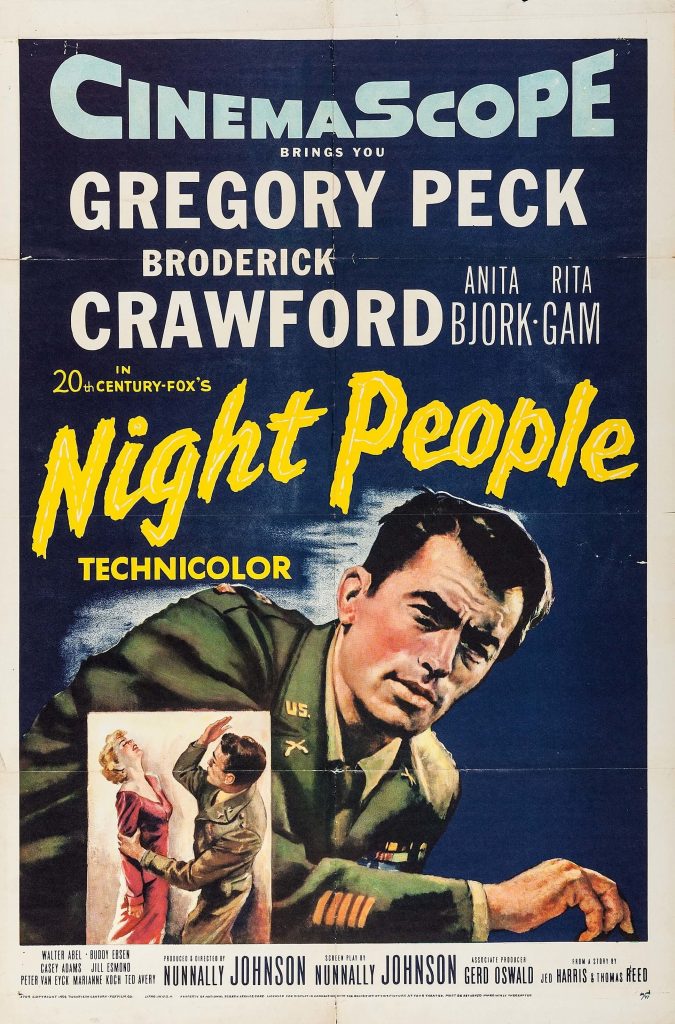

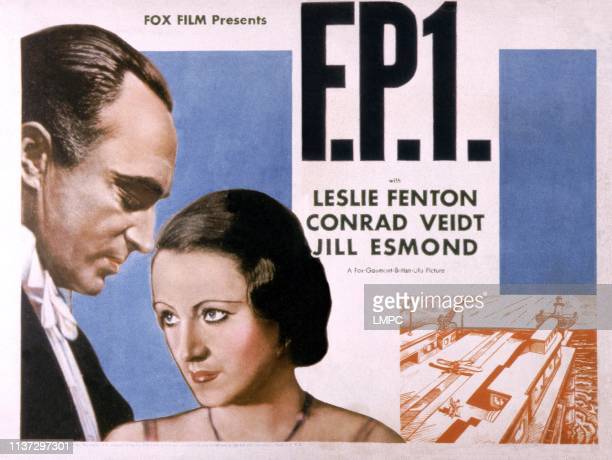

Jane has one older brother, Peter, later half of the earnest Peter and Gordon singing duo responsible for “A World Without Love” (he’s now vice- president of Sony Music) and a younger sister, Clare, who’s a teacher and Ofsted inspector. All three red-haired children trod the boards and the celluloid at tender ages. Were their parents stage-struck? “My father used to do a lot of amateur acting, and my mother’s father has a local theatre company in Cornwall, so there was a lot of family interest. It started as a little hobby, really, but I took it very seriously.” Sure did. By 15, she had been on television nine times, done 100-odd radio broadcasts, eight films and four plays. Then, as the world knows, she met Paul McCartney at 17, was pronounced a “rave London bird” and became The Well-Known Girlfriend for five years. She co-starred with Michael Caine in Alfie (she was the one with the diary who outraged the Cockney Lothario by having “private thoughts” while ironing his shirts). At 25, she married Gerald Scarfe, the Rembrandt of lampoonists, and 27 years later, they’re together still, despite appearing in Hello! magazine (“but then we’ve never done a proper Jane-and-Gerry-brag-about-their-happy-marriage thing. That’s the killer”).

She disappeared from public view when she started raising children (Kate, now 23, Alexander, 16, and Rory, 14), reappeared in 1982 and now, at 52, is in gratifyingly constant demand, playing nice wifely figures on television and coldhearted bitches on stage. She is currently to be seen in Alan Ayckbourn’s new play, Things We Do For Love, in the West End. “I play Barbara, a defensive and prickly woman who’s been living on her own for ages, whose little foibles and intolerances have become exaggerated until she’s literally repellent. But lust breaks down her barriers, as it changes everyone in the play.” Ms Asher wrinkles her gorgeous nose. “It’s … interesting to play someone who’s exploding from within.” She loves being directed by Ayckbourn in person. “It’s wonderful to have a living author who can tell you about his intentions. And Alan knows just where he’s taking you from the word go and does it in a very gentle and enjoyable way.”

Ms Asher is not impervious to criticism (“Nicholas de Jongh in the Evening Standard said I was far too erotically alluring. Now, I can live with that criticism”), but has, I suspect, reached the stage where plaudits in the showbiz pages impress her as little as speculations on her love life in the Sixties. She’s anxious to prove herself as a competent novelist, and that’s enough for the present. Did she regret not having pursued a Hollywood career and consequently not attending this year’s Oscar ceremony in an Alexander McQueen frock? Did she hell. “I’d love to have gone to the Oscars. But, genuinely, I’m too aware of what an interesting life I have to regret anything,” she says, smiling her toothy smile. “I’d like to have had six lives – to be an enormously successful Shakespearean actress, a Hollywood film star, an earth mother staying at home baking bread on the farm and having 19 children, a brilliant doctor. But I don’t regret not pursuing any one of those because I’ve had such a good time”

The above article can be also accessed online in “The Independent” here.