Brittish Actors

Zara Turner appeared alongside Gwyneth Paltrow and John Hannah in the 1998 romantic drama film Sliding Doors, and as Dr. Angela Moloney (again with John Hannah) in the television series McCallum (1995–1998).[1] In 2001, she appeared in the comedy film On the Nose as Carol Lenahan, with Dan Aykroyd and Robbie Coltrane.

Turner has won the Best Actress award at the Reims International Television Festival and the Golden FIPA at the 2004 Festival International de Programmes Audiovisuels.

Ms Turner is married to fellow actor Reece Dinsdale and they live in Yorkshire, England with their children

Wikipedia entry:

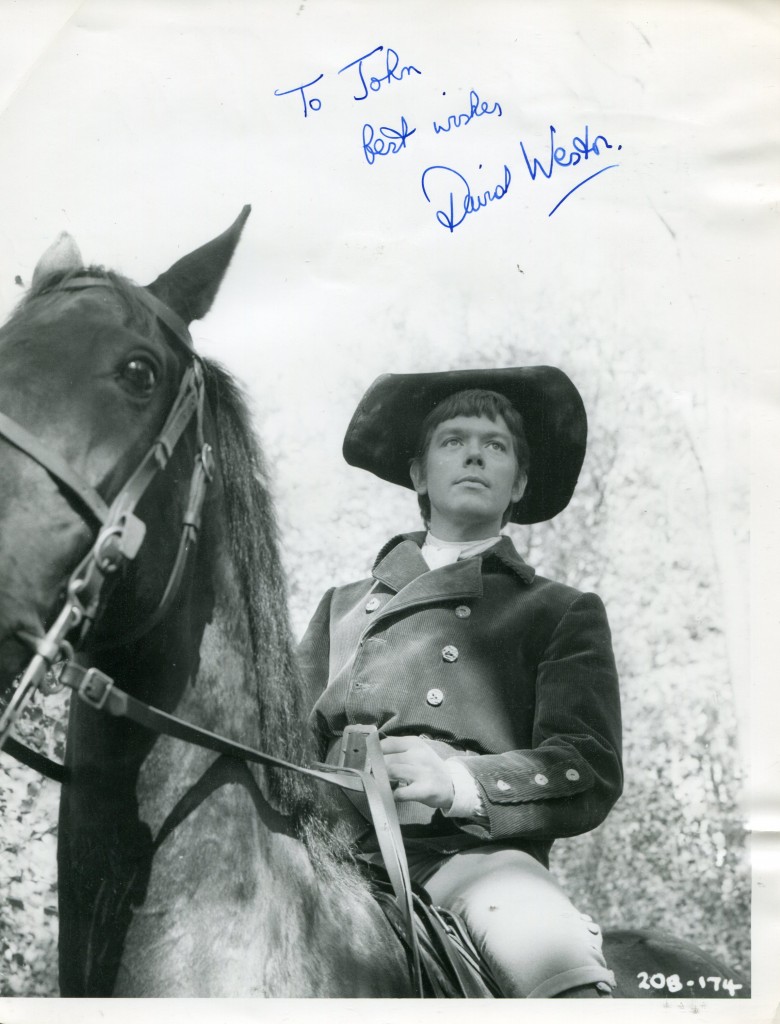

David Weston (born 28 July 1938, London) is an English actor, director and author. Since graduating from RADA in 1961[1] (having won the Silver Medal for that year)[2] he has acted in numerous film, television and stage productions, including twenty-seven plays in Shakespeare‘s canon. With Michael Croft he was a founder member of the National Youth Theatre.[3] Much of his directing work has been for that organisation; he has directed also at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre and a number of other theatres in London. He wrote and narrated a series of non-fiction audio books, including Shakespeare His Life and Work which won the 2001 Benjamin Franklin Award

Weston was educated at Alleyn’s School, Dulwich, during the time that Michael Croft, founder of the National Youth Theatre, was there creating drama of a very high standard.[4] In 1956 Croft directed a school production ofShakespeare‘s Henry IV, Part 2, which, when revived as a NYT production at the Toynbee Hall Theatre the following year, attracted the attention of the national press. Weston played Falstaff, a character singled out by The Times in its praise of the play’s comedy.[5]

In August 1960 Weston played Mark Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar at the Queen’s Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue. Directed by Croft and given in modern dress, this was only the second appearance by the company of the NYT in London’s West End. John Shrapnel played Caesar, Neil Stacy Brutus and Alan Allkins Cassius. The play was judged a “youthful success” by the theatre critic of The Times; Weston’s performance was said to have successfully caught an opportunist spirit effectually hidden by a rough charm.[6]

The Times was more muted in its praise of the Electra and Oedipus Rex of Sophocles in a double bill put on by RADA at its Vanbrugh Theatre, Bloomsbury in February 1961. Weston played Creon in Oedipus Rex; his bluff characterisation was described as strongly supportive.[7]

Weston’s first television appearance was as Romeo in a production for schools of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet; Jane Asher played Juliet.[8]

In 2011 Weston published Covering McKellen: An Understudy’s Tale, a memoir of the year he spent as Ian McKellen‘s understudy in the Royal Shakespeare Company‘s tour of King Lear directed by Sir Trevor Nunn.[9]

In 2014 Weston published Covering Shakespeare: An Actor’s Saga of Near Misses and Dogged Endurance, a memoir of his experiences performing in productions of Shakespeare’s plays.[10]

Michael Jayston was born on October 29, 1935 in Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England as Michael James. He is an actor, known for Nicholas and Alexandra (1971),Emmerdale (1972) and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1972). He has been married to Elizabeth Ann Smithson since 1978. They have two children. He was previously married to Heather Mary Sneddon and Lynn Farleigh.

Michael Smiley was born in 1963 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He is an actor, known forPerfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006), The World’s End (2013) and Kill List (2011). He is married to Miranda Sawyer. They have one childIn 1993 he was a runner up at the So You Think You’re Funny competition at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival

If you don’t already own a bicycle then be prepared to want to rush out and buy one after you hear how the star of stand-up, TV![]() and film enthuses about them

and film enthuses about them

The Holywood-born comic and actor believes bicycles are THE best invention of the past 100 years.

While Michael’s acting career has seen him star in a long and impressive list of movies and TV dramas, last year he landed his dream job when BBC Northern Ireland asked him to hop on his bike and visit many of his old stomping grounds around the province for a new three-part series.

Beginning tonight, Something To Ride Home About sees Michael indulge his infatuation for cycling, giving his own unique comic insight into the places and the people who share his zeal for two wheels.

It was his love affair with bikes which led to his acting debut when a friend created a character for him – Tyres O’Flaherty, the bicycle riding raver who starred in two episodes of the cult Channel 4 sitcom![]() Spaced.

Spaced.

It was based on Michael’s days working as a cycle courier in London before he got his big break on stage as a stand-up comic.

Currently in Kerry filming sci-fi romance The Lobster with Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz, Smiley is very open when I ask him about all aspects of his life and career.

Strikingly, even though he has lived in London for the last 30 of his 51 years he hasn’t lost an ounce of his strong Northern Irish accent. Nor is there a hint of a superstar ego, despite his considerable success and fame as both a comic and actor.

Married twice and a father of four, Michael and his first wife Merilees – whom he describes as his childhood sweetheart – left Northern Ireland in 1983 to start a new life in London.

The couple, who are still best friends, have two children, Dillon (30) and Jasmine (26).

Michael’s second wife, meanwhile, is journalist![]() and broadcaster Miranda Sawyer, with whom he has two children, Patrick (8) and Frankie May (3).

and broadcaster Miranda Sawyer, with whom he has two children, Patrick (8) and Frankie May (3).

Incidentally, Merilees is godmother to his two younger children. He says: “We all get on great and are best mates.”

Michael grew up in Redburn in Holywood and recalls the story of his birth which he says his late parents were often fond of telling him: “I was born in my mum and dad’s bedroom in the winter of 1963.

“The snow was up to the window ledge and my poor dad had to walk to my granny’s house in Belfast to get milk and coal. It was that winter everyone references as one of the worst and my first cot was a bottom drawer in my mum’s dresser.

“I was the baby of the family. I have a brother, John, who lives in America and a sister, Collette, who still lives in Holywood. My mum passed away three years ago and my dad seven years ago and my big sister is great, she has always been there for me.”

Growing up he describes himself as “a wee tearaway” who was “always chasing girls, blowing smoke and drinking cider”.

Mum Alice was a seamstress and dad Frank a post office engineer, and they worked and saved hard to give their youngest a good education, paying for him to go to boarding school from the age of 11 until 16.

“Unfortunately it didn’t really work,” says Michael. “I wasn’t an ideal pupil. I was a bit skittish and had a short attention span and was really hyperactive. I still haven’t settled down.

“After boarding school I went to college in Belfast but I felt slightly disjointed and in the Eighties there was nothing really happening in Northern Ireland apart from the Troubles.

“There was a bit of a music scene in Belfast but no big bands were really coming to the city and I didn’t know any creative people back then, no writers or actors or musicians.”

He decided to move to London when he was 20 with no real career goal.

He did various jobs working on building sites and spent some time on the dole before getting a job as a cycle courier.

It was a friend who recognised his natural talent for making people laugh and persuaded him to go on stage at an open mic night in London in 1993.

“He used to drag me to comedy clubs and one night persuaded me to take a slot which I did and my life changed,” recalls Michael.

“It was amazing. I got up on stage and I was so excited and nervous and that night I couldn’t sleep. I just felt this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.

“I started to write material and for the next 20 years I did stand-up all over the world.”

He was writing and performing one-man shows in Edinburgh when he got the chance to make his acting debut in 1999 in a role that was specially written for him.

“Simon Pegg and Jessica Stevenson were writing Spaced for Channel Four and they based the character Tyres O’Flaherty on me from my time as a cycle courier. They asked me to play him and I jumped at it.”

Two series of seven episodes![]() of Spaced each were broadcast in 1999 and 2001 on Channel 4, and became an instant cult hit, not only for the witty dialogue and numerous pop culture references, but also the ‘will they, won’t they?’ relationship of the two leads.

of Spaced each were broadcast in 1999 and 2001 on Channel 4, and became an instant cult hit, not only for the witty dialogue and numerous pop culture references, but also the ‘will they, won’t they?’ relationship of the two leads.

A long list of acting roles followed including playing Jordan, a former member of the Parachute Regiment, in 2008 horror film![]() Outpost, as well as a Tyres-like zombie cameo in old pal Pegg’s movie Shaun Of The Dead.

Outpost, as well as a Tyres-like zombie cameo in old pal Pegg’s movie Shaun Of The Dead.

In 2003, he guest starred in the Doctor Who audio drama Creatures Of Beauty and in 2004 appeared in an episode of Hustle as Max the forger.

He has also appeared in all three series of The Maltby Collection on Radio 4 as Des Wainwright, an eccentric security guard who keeps repeating himself and reminding people he was in the SAS. In 2010, he reunited with his Spaced co-stars for a major role in the film Burke And Hare and further cemented his cult credentials in 2011 after starring in the graphic and bleak British horror film Kill List.

The film received critical acclaim, and earned him the Best Supporting Actor award at the 2011 British Independent Film Awards.

Last year he appeared in an episode of BBC1’s Ripper Street as George Lusk, and the critically acclaimed Channel 4 shows Utopia, as Detective Reynolds, and Black Mirror, as Baxter.

The list of credits goes on and on and this year he has been just as busy, playing Micky Murray in BBC Four’s The Life Of Rock and filming one of the first episodes of the eighth full series of Doctor Who, playing a character by the name of Colonel Blue. While he is enjoying great success and increasing recognition, Michael remembers all too clearly what it was like to be unemployed. “I spent a long time not knowing what I wanted to do and being fearful of life and worrying about not being able to support my wife and family,” he says.

“It wasn’t a happy time for me, but I am blessed with good friends and beautiful relationships in my life.

“It took other people to see the talent and I think that for many people it takes those who love you to help you.

“At school I never settled and was always the class joker. Now I’m older I realise that exams at school give you the ability to concentrate.

“Its only now that I am capable of doing that, although there is still a wee part of me that wants to run around and blow raspberries.

“Real success takes work. It has taken me 20 years to be an overnight success.

“You have to work hard; it doesn’t just drop in your lap. Each time you learn from your mistakes and so the next time you can do it better.

“It’s like an education for my soul. I feel like I am learning every day now when I wasn’t as a child.”

Although he does return home from time to time to see his sister, his new BBC series filmed last year was his first chance to spend some quality time at home since he left for London 31 years ago.

The fact that he got to spend it indulging his passion for his beloved cycling was incredible to him, and it’s obvious he loved every minute.

He lifts cycling onto a whole new plain as he extols its many virtues. “I’ve always had a love affair with cycling. Bicycles are by far the best invention of the past 100 years, they save your life.

“People in villages were able to escape and find work through bicycles and were able to shop for food at markets and get their kids to school.

“Cycling helps you get fitter and it also helps the planet. It calms the body and dispels depression.

“If you are feeling p****d off, just cycle for five minutes and I can guarantee you that you won’t be feeling that anymore.

“You meet other cyclists and it lifts your spirits. It’s not like being stuck in a gym – you are out in the countryside, smelling our cows*** and freshly-cut grass and feeling the sun on your face and the rush of fresh air. You meet a better class of people and as HG Wells said, ‘When I see an adult on a bicycle, I no longer despair of the human race’.”

On his travels with the series he rides some of our most stunning local scenery, tries some alternative cycling disciplines and meets a number of local enthusiasts including a world record holder, and Newtownards-born cycling world championship gold medallist – and BBC NI Sports Personality of The Year 2013 – Martyn Irvine.

“The fact it wasn’t studio-based really appealed to me, I loved it,” says Michael.

“Chris Jones of Green Inc had the idea for the series and I just thought it was fantastic.

“When I left Northern Ireland in the 1980s I remembered it as being very parochial back then.”The show made me realise there were three types of people in Northern Ireland during the Troubles – the ones who left and never came back, the ones who left but came back and the people who stayed. To me the people who didn’t leave are the real heroes”Despite all the rubbish that was going on they stayed and educated their kids and did what they could under difficult circumstances. It was incredible to get the chance to talk to these people and to get a bit of the Northern Ireland craic. “No one has a turn of phrase like we have here, or the humility.

“I got to talk to Isobel Woods in her home. Isobel set and held Irish records for cycling which were not broken until about six years ago. “She still holds seven records no one has broken. “She broke my heart, she is my hero, and I just fell in love with her.” The show has renewed Michael’s love for his home country and has given him a new goal – to buy a camper van and tour Ireland with his children. “Sadly I haven’t got back home much over the years, mainly for funerals,” he says. “I am going to change that next year and buy a Mazda Bongo and take my children touring the north and south of Ireland.”

Michael Smiley: Something To Ride Home About begins on BBC1 Northern Ireland tonight at 10.20pm

In Something to Ride Home About, Michael begins his journey in Belfast and visits St George’s Market, before meeting one of only six Penny Farthing owners in Northern Ireland. Meanwhile, viewers also get a sneak peek behind the doors of a community cycle workshop which provides repairs and servicing for bikes in the city. And after a visit to his home town of Holywood, Michael gets to meet keen cyclist, acclaimed photographer and one of his own personal heroes, Bill Kirk, in Newtownards.

He also experiences a hairy moment with a ladies cycling club in Armagh, drops in on a world record holder in Lisburn, puts himself on trial against the clock in Dungannon and meets a fellow comic on the banks of the Foyle. Producer Chris Jones, from Green Inc, says: “In my opinion, Smiley is our finest actor and funniest comedian. “We were thrilled to be working with him on this series that lets Michael revel in two things he’s brilliant at: cycling and telling funny stories.

“It’s his first outing as a presenter on a BBC NI series and you won’t need to be a cyclist to enjoy it. Yes, although Smiley is a keen cyclist he didn’t cover the full length and breadth of Northern Ireland but he certainly brings us to some breathtaking and interesting places and we get to meet some very fascinating people with great stories to tell with a lot of laughs guaranteed along the way with Michael. Maybe it might inspire some people to get on their bike!”

The above “Belfast Telegraph” article can also be accessed online here.

IMDB Entry:

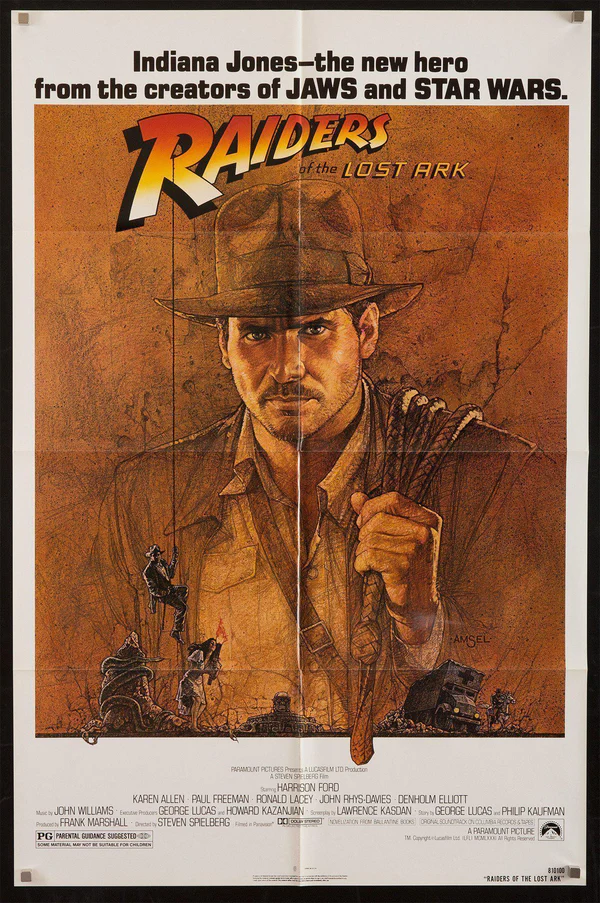

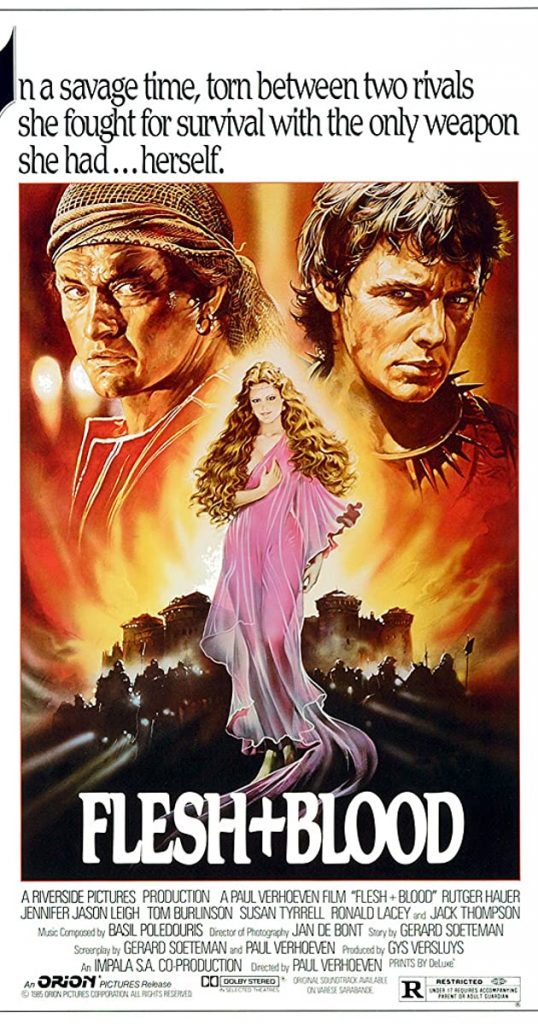

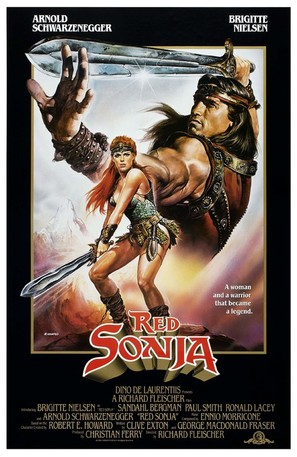

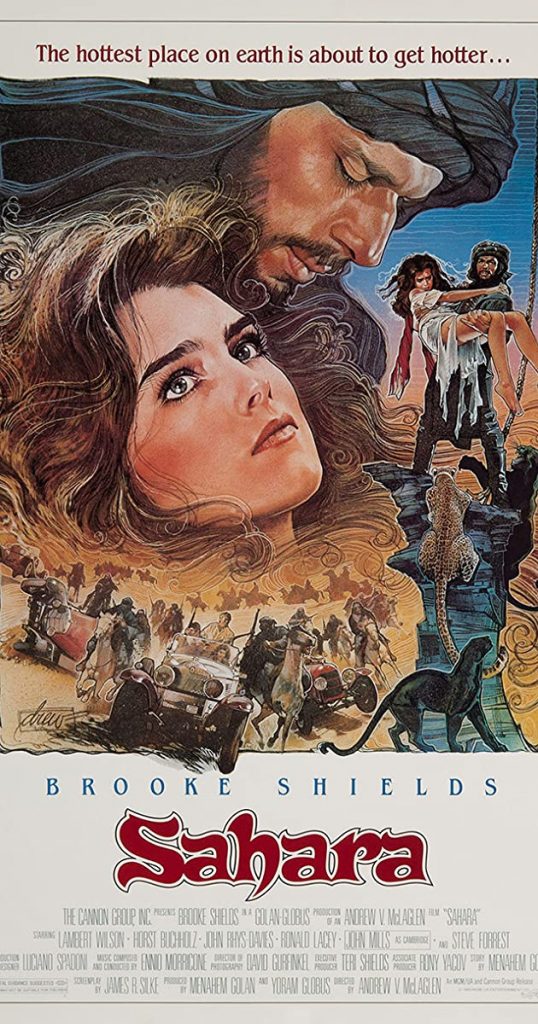

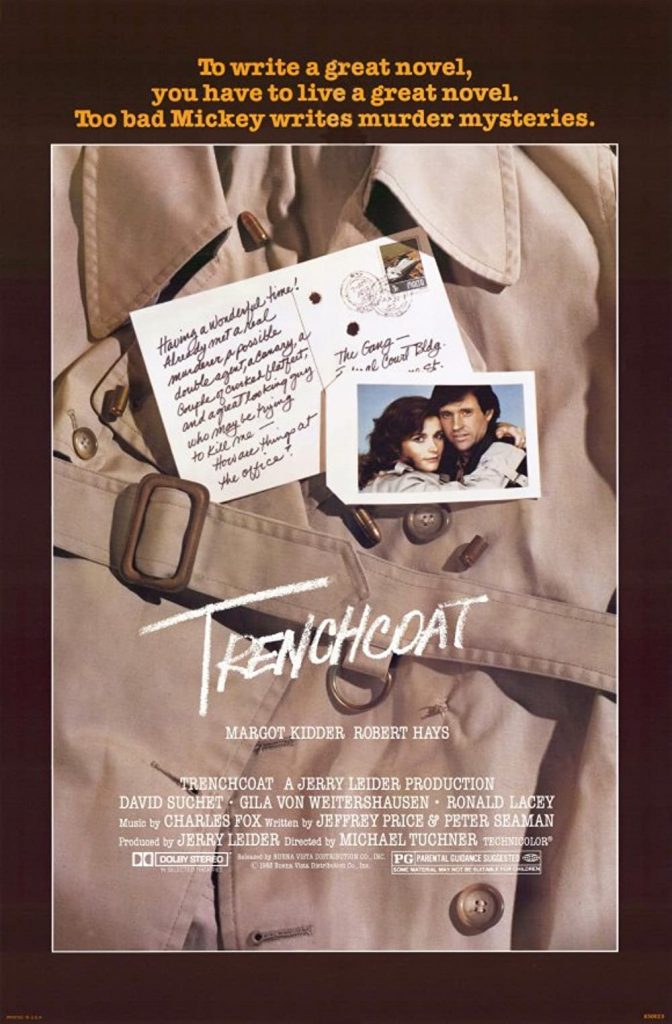

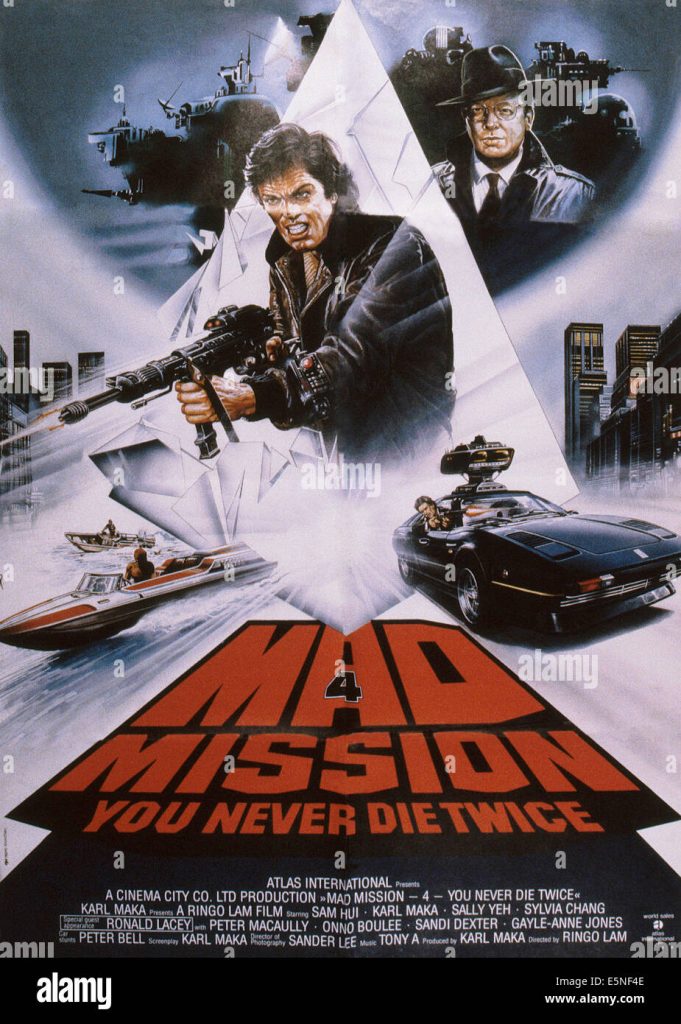

Ronald Lacey was born on June 18, 1935 in the suburbs of London. He began his career in 1961 after a brief stint in the Royal service. He attended The London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts. His first notable performance was delivered at The Royal Court in 1962’s “Chips With Everything”. Lacey had an unusual pug look with beady eyes and cherub’s cheeks which landed him repeatedly in bizarre roles on both stage and screen. However it was his unforgettable demonic smile and peculiar Peter Lorremannerisms that would bring Lacey a short period of fame in Hollywood. After performing on British television throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s, Lacey finally landed the role for which these characteristics could be used to full advantage. In 1981 he was cast as the villainous Nazi henchman in ‘Steven Spielberg’ ‘s widescreen blockbusterRaiders of the Lost Ark (1981) He followed this with a series of various villainous roles for the next five to six years: Firefox (1982) with ‘Clint Eastwood’, Sahara (1983) withBrooke Shields, and Red Sonja (1985) with Arnold Schwarzenegger. Lacey turned in two hilarious cinematic performances in full drag (Disney’s Trenchcoat (1983) with Margot Kidder from 1982 and Invitation to the Wedding (1983) from 1985 – in which he played a husband/wife couple!). Sadly his career began to wane in the late eighties and Lacey died in London of liver failure on May 15, 1991. A tremendous talent with great depth and many facets, Ronald Lacey will be remembered best for his small but significant role as the dapper yet psychotic Nazi in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Michael Loris

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

by Pete Stampede

Ronald Lacey’s character’s name in “The Joker,” Strange Young Man, aptly sums up most of the parts he played. He was once memorably described by leading theatre critic Michael Billington as “looking like a cherub versed in the works of the Marquis de Sade.” His entry into TV was in The Younger Generation (Granada, 1962), built around a repertory company of actors, all under 30 at the time; John Thaw and future film director Bill Douglas were other members of the company, and Michael Caine had a guest role in Lacey’s starring segment—regrettably, not a single episode of this series still exists. Lacey soon found a niche in TV plays, notably John Hopkins’ ambitious, anti-racist Fable (1965), and Boa Constrictor (1967), a typically bitchy work from Simon Gray. He later turned in a bravura performance as Dylan Thomas in Dylan (BBC, 1978). Lacey was the village idiot in Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers (UK: Dance of the Vampires, 1967) (he looked a bit like Polanski, come to think of it), and for the rest of his film career, including a Hollywood spell in the 80’s, was predominantly cast in the fantasy genre, suiting his talent for playing the weird and obsessed—The Final Programme (1973, for Avengers director Robert Fuest), The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the Eighth Dimension (1984), Flesh and Blood, and Red Sonja (both 1985).

But his most notable role, overall, was as a Gestapo man with a fondness for wire coat hangers in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). He returned the favour with an unbilled cameo in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). Other TV guest appearances include a beatnik who witnesses the murder of Hopkirk in the premiere episode of Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased), “My Late, Lamented Friend and Partner” (1969), an assistant to Dennis Price in several episodes of Jason King (1971-72), a nasty little jailbird called Harris in Porridge (again, a recurring role), and a memorably revolting turn as the baby-eating Bishop of Bath and Wells in Blackadder II, “Head” (1985). In a classic episode of The Sweeney, “Thou Shalt Not Kill!” (1975), he was one of a pair of tooled-up blaggers—er, that’s “armed robbers” in Sweeney-ese—who cause a siege at a bank. I’m afraid I also remember an episode of Hart to Hart in which he and the lovable Bernard “Dr. Bombay” Fox had to pretend to be French. It came as a shock, in 1991, to hear of Lacey’s death (from liver failure). He was the type of actor who, having been around for so long, you expect to go on for ever.

Tony Garnett obituary in “The Guardian” January 2020.

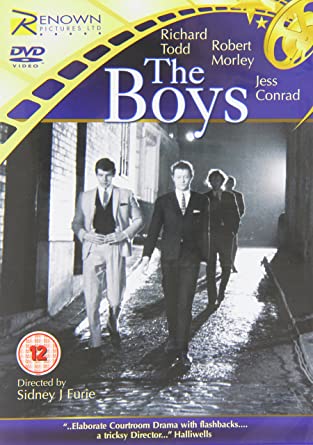

Tony Garnett was born on April 3, 1936 in Birmingham, West Midlands, England. He is a producer and actor, known for Beautiful Thing (1996), Kes (1969) and Earth Girls Are Easy (1988). In 1962 he starred in “The Boys”.

Tony Garnett, who has died aged 83, was a hugely influential creator of British film and television drama, from excoriating early work such as Cathy Come Home and Up the Junction, to the classic film Kes and the popular television series This Life and Ballykissangel.

He left acting behind to become a groundbreaking producer who made waves with both the socially and politically charged stories he brought to the screen and the chillingly realistic way in which they were filmed. The early part of his career was dominated by his partnership with the director Ken Loach, who pioneered a social-realist style of film-making that blurred the lines between fact and fiction.

Among the first to put working-class voices on screen, they joined the BBC during a creative period that flourished under the liberal regime of director general Hugh Greene. However, their two most explosive dramas together – for the Wednesday Play slot – were challenging even to “benign” BBC bosses.

Garnett was still a story editor on the stand-alone drama series when they made Up the Junction (1965), adapted by Loach from Nell Dunn’s 1963 book of vignettes depicting everyday life in Battersea, south-west London. It featured “factory girls”, dirty streets, crumbling houses, bawdy language and casual sex. At its core was a scene of a backstreet abortion, two years before terminations were legalised.

Garnett knew the Wednesday Play’s producer, James MacTaggart, would be unhappy with it, so set the production in motion while his boss was on holiday. “It was a case of, ‘If the cat’s away, the mice will play,’” Garnett explained to me in 2002. “When Jim arrived back from his holiday, he hit the roof. I had a huge, apoplectic, stand-up row in his office that went on for days.” Nevertheless, MacTaggart allowed filming to continue because Garnett felt so strongly about it. “It was very important to me, for personal reasons,” added Garnett.

Fourteen years later, in his memoir, The Day the Music Died, he revealed that his mother, Ida (nee Poulton), died of septicaemia after having a backstreet abortion when he was five. His father, Tom Lewis, a garage mechanic who switched to selling insurance, took his own life 19 days later. When Up the Junction was screened, it caused uproar in the rightwing press and was attacked by the Clean Up TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse, although Garnett seemed to relish this as “an added frisson”.

He then became a producer and with Loach – who regarded him as being good at the “corridor politics” – made an even bigger impact with what became the most famous TV play of the 20th century, Cathy Come Home (1966).

Jeremy Sandford’s script about homelessness was brought to Garnett’s attention by Dunn, the writer’s then wife. It was an attack on council house waiting lists and the policy of separating husbands from their homeless wives and children. Loach reworked the script with Sandford while Garnett was “economical with the truth” in discussions with BBC management.

The public and political outrage that followed the screening of Cathy Come Home, featuring Carol White and Ray Brooks as the couple whose family was torn apart, speeded up the formation of Shelter.

It was another experience of his own heartache that led Garnett to commission In Two Minds, David Mercer’s 1967 Wednesday Play about schizophrenia. Repudiating the traditional view that it was a disease with an organic basis, the play incorporated the ideas of a new wave of psychiatrists, led by RD Laing, who believed it could be caused by internal family relationships.

Mercer had experienced depression himself, and Garnett had been witness to the sudden decline in mental health of his wife, Topsy Jane, who starred with Tom Courtenay in the 1962 film The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and had seemed set for a glittering screen career.

Cast as Courtenay’s girlfriend in Billy Liar (1963), she fell ill several weeks into filming, was replaced by Julie Christie, diagnosed as schizophrenic and given electroshock therapy. “She had been sent back someone else … the opposite of the woman I knew,” wrote Garnett. Later, he and Loach remade In Two Minds as a feature film, Family Life (1971).

In between, they made the film Kes (1969), which became a British classic, based on Barry Hines’s novel A Kestrel for a Knave. The story, adapted by Garnett, Loach and Hines, features a 15-year-old Yorkshire boy, Billy Casper (played by David Bradley), who – failed by the education system – finds satisfaction in training a wild bird while facing a certain future down the local pit. Garnett was one of those who gave Loach an awareness of socialism that would inform all his future work, and to Hines he gave encouragement.

Another writer he encouraged was Jim Allen, who wrote Days of Hope (1975), a four-part epic for the BBC tracing the betrayal of the working class by the trade union and Labour party leaderships in the years leading up to the general strike of 1926.

Then, in 1979, worn down by years of battling to get TV and film productions made – and a dissatisfaction with the country’s move to the right politically – Garnett left Britain for the US.

His decade there was relatively fruitless, but he returned home to create World Productions and launch a new wave of innovative, challenging dramas such as Between the Lines (1992-94) and This Life (1996-97), alongside the more mainstream Ballykissangel (1996-2001). For the first time, while bringing on a new generation of writers and directors, he was producing series designed to have long runs, with repeat commissions.

Garnett was born Anthony Lewis in the Birmingham district of Erdington. Following the death of his parents, he was brought up by his Auntie “Pom” (Emily) and Uncle Harold, while his younger brother, Peter, went to other relatives. “I automatically closed down, feeling nothing,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I never cried.” He retained his father’s surname but switched to his uncle’s, Garnett, in his late teens.

As a child, he was an inveterate reader and attended Birmingham’s central grammar school, where he acted in school plays. While performing with amateur groups, he fell in love with Topsy Jane Legge.

Garnett then joined rep companies before studying psychology at University College London, where he acted with its drama society. Spotted by a BBCproducer, he was given small roles in An Age of Kings (1960), an anthology of Shakespeare’s history plays. More screen appearances followed, including parts in Mercer’s television plays A Climate of Fear (1962) and The Birth of a Private Man (1963), and in the film The Boys (1962), as a teenager on trial for murder.

He joined the Wednesday Play as an assistant story editor and, on promotion to story editor, worked on Dennis Potter’s Vote, Vote, Vote, for Nigel Barton and Stand Up, Nigel Barton (both 1965).

In addition, Garnett produced two other plays by Allen, The Lump (1967) and The Spongers (1978), as well as Hard Labour (1973), the director Mike Leigh’s first TV drama, and Law & Order (1978), GF Newman’s controversial take on the legal system, directed by Les Blair, another of Garnett’s proteges, who also included the writers Leon Griffiths and Charles Wood, and directors Jack Gold, Roy Battersby and Roland Joffé.Advertisement

Garnett left the BBC for a couple of years, and with Kenith Trodd set up Kestrel Productions, making dramas for the newly launched ITV company LWT. These included his own collaboration with Loach, After a Lifetime (1971).

During the 1960s and 70s, Garnett often hosted evening meetings on Fridays with Trodd and like-minded leftwingers – at a time when MI5 was secretly vetting those employed by the BBC. There was an attempt to block Garnett’s return to the corporation that was overruled because of his professional ability. Later, he himself had to threaten to resign in order to be allowed to employ Joffé.

Garnett then wrote and direct- ed two films: Prostitute (1980), focusing on the working lives of sex workers, in Britain, and Handgun (1983), about a female victim of rape seeking revenge, in Texas.

His time as a film producer at Warner Bros in Hollywood bizarrely yielded only the Sesame Street spin-off Follow That Bird (1985) before he made the musical Earth Girls Are Easy (1988) and the atom bomb drama Fat Man and Little Boy (1989), starring Paul Newman.

Setting up World Productions in 1990 enabled him to work outside the BBC, which he criticised as having become a massive bureaucracy that stifled creativity. His company’s other programmes for it included Cardiac Arrest (1994-96), The Cops (1998-2001), Attachments (2000-02) and Rough Diamond (2006).

On his return to London in 1990, Garnett set about exorcising the demons of his past and underwent five years of psychoanalysis. He said it moved his grief on to mourning and accepting the deaths of his parents and the “existential death” of Topsy Jane. Their 1963 marriage ended in divorce; she died in 2014.

He is survived by his partner, Victoria Childs, and his sons Will, with Topsy Jane, and Michael, from his second marriage, to Alex (nee Ouroussoff), which also ended in divorce.

• Tony Garnett (Anthony Edward Lewis), producer, writer and director, born 3 April 1936; died 12 January 2020

TCM Overview:

A dashing and handsome English-American actor, Peter Lawford enjoyed a brief stint as a matinee idol in the 1940s before becoming better known as an in-law of the Kennedys and a member of “The Rat Pack” during the 1960s. Benefitting greatly from the dearth of handsome male talent in Hollywood during World War II, Lawford gained notice for appearances in such films as “The Picture of Dorian Gray” (1945) and “Son of Lassie” (1945). More roles followed throughout the 1950s, although it was his marriage to Patricia Kennedy – sister of John and Robert Kennedy – as well as his association with Frank Sinatra’s iconic cadre of carousers that brought Lawford lasting fame. Years after JFK’s assassination, rumors about Lawford’s scandalous adventures with the president, his being the last person to speak to a despondent Marilyn Monroe before her tragic death, and a bitter falling out with Sinatra, became the stuff of legend. Less glamorous was Lawford’s decline in the film industry, several failed marriages, and chronic alcoholism. With the halcyon years of “Ocean’s Eleven” (1960) far behind him, the aging actor made due with the occasional film role and guest turns on such TV fare as “The Doris Day Show” (CBS, 1968-1973) and “Fantasy Island” (ABC, 1977-1984). A bit player in a fascinating chapter of American pop-culture, Lawford would most likely be remembered less for his acting credentials than for the legacy encapsulated in author James Spada’s unofficial biography, Peter Lawford: The Man Who Kept the Secrets.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.