Jean Marsh. TCM Overview.

Jean Marsh was born in London in 1934. She started her acting career on the stage. Her first film was “The Limping Man” in 1953. Throughout the 50’s and 60′ she guest starred in many of the television series of the day. In 1959 she went to Hollywood where she woked on television including an episode of “The Twilight Zone”. In 1971 she and her friend Eileen Atkins originated the concept for a television series based on the experiences of their parents who had worked in service in some of the garnd houses in England. Thus “Upstairs, Downstairs” was born. The series was hughely successful both in Britain and in the U.S. Jean Marsh played Rose the upstairs parlor maidn who eventually became the ladies maid. The series ran until 1974. hen then went to the U.S. where she acted in films and television in Hollywood and on the stage on Broadway. She returned to Britain to make the film “Willow”. jean Marsh is also a published novelist.

TCM Overview:

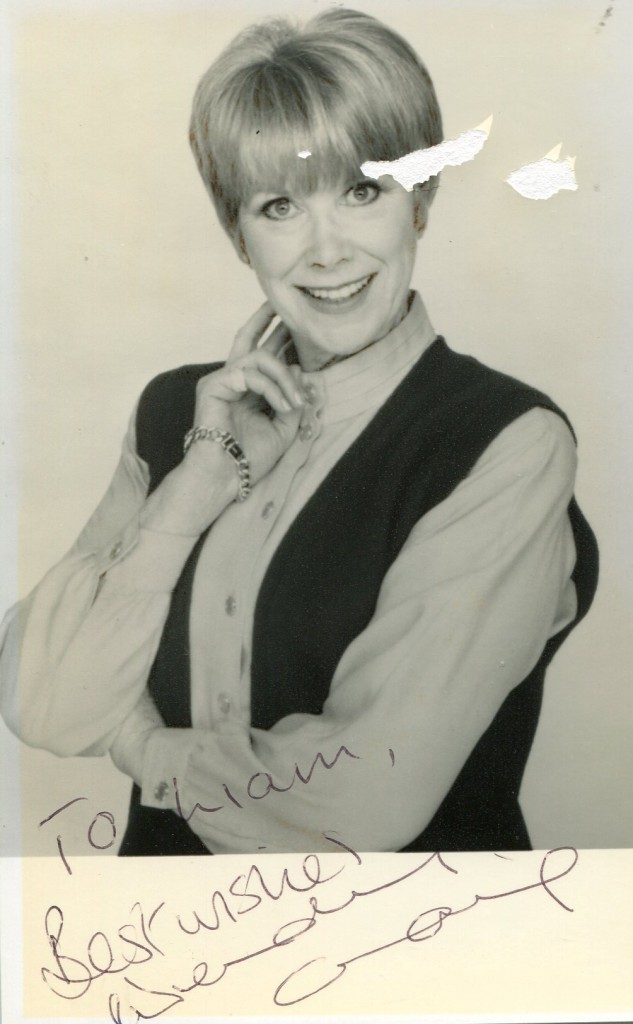

A genuine class act, Jean Marsh won raves in her native England and on American soil for taking on nuanced roles onscreen. The Emmy Award-winning actress first made her mark in British productions, from Shakespearean stage revivals, to sci-fi epics, to costume dramas. However, it was Marshâ¿¿s breakout performance on “Upstairs, Downstairs” (ITV, 1971-75), a period drama series she also created, that earned the actress favorable reviews on both sides of the Atlantic. Her role as a prim and proper housemaid to an aristocratic British family won Marsh an Emmy in 1975, establishing her presence in Hollywood. She parlayed her success on British television into big screen projects, often playing the villain in feature films such as “Return to Oz” (1985) and “Willow” (1985). In 2010, Marsh starred on the three-part revival of “Upstairs, Downstairs,” which garnered more critical praise and gave her the opportunity to reprise one of the best characters in her long revered career.

Jean Lyndsay Torren Marsh was born on July 1, 1934 in the Stoke Newington district in London, England. Her father was a printerâ¿¿s assistant and maintenance man, while her mother worked as a dresser for the theater and also tended a bar. Marsh studied acting and mime as a child before taking her first steps in the entertainment business as a cabaret singer, model and dancer. She first graced the Broadway stage in a 1950s production of “Much Ado About Nothing” with acclaimed British actor, director and producer John Gielgud. Marsh made her onscreen acting debut in the made-for-television movie “The Infinite Shoeblack” (BBC, 1952).

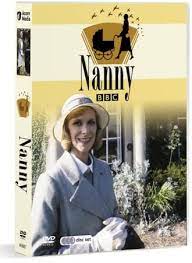

The actressâ¿¿ early career consisted of several appearances on television, from playing a female robot in an episode of “The Twilight Zone” (CBS, 1959-1964), to appearing on “Walt Disneyâ¿¿s Wonderful World of Color” (ABC, 1954-1961; NBC, 1961-1981; CBS, 1981-83; ABC, 1986-88; NBC, 1988-1990) and “I Spy” (NBC, 1965-68). Yet it was on British television where Marsh established her career with recurring roles on the original installment of the long-running science fiction drama “Doctor Who” (BBC, 1963-1989). She first appeared on the series in 1965 as a medieval crusader and continued to guest star until 1989.

In 1971, Marsh and fellow British actress Eileen Atkins created the drama series “Upstairs, Downstairs” about a wealthy family living in London and the housemaids who served them. Marsh played Rose Buck, the head parlor maid of an aristocratic household. Playing the prim and proper servant earned the actress an Emmy Award in 1975 for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series, a category she was also nominated for in 1974 and 1976. Additionally, she was nominated twice (1975 and 1977) for her work on “Upstairs, Downstairs” in the Best TV Actress

Drama category at the Golden Globe Awards. After several guest appearances on American television, Marsh landed a supporting role on the short-lived comedy series “Nine to Five” (ABC, 1982-83). Based on the 1980 film of the same name, “Nine to Five” followed three friends (Rachel Dennison, Valerie Curtin and Sally Struthers) as they navigated their careers, friendship, and love lives in the corporate world.

Marsh further enthralled audiences by playing a villain in feature films, including the wicked witch Mombi in “Return to Oz” and the evil sorceress Queen Bavmorda in “Willow.” Twenty years after “Upstairs, Downstairs” premiered, Marsh and Atkins reteamed to create “The House of Eliott,” about two dressmaking sisters living in 1920s London. Both Marsh and Atkins, however, did not act on the show. Marsh easily slipped back into a villainous character with a recurring role on the young adult series “The Tomorrow People” (ITV, 1992-95) as a mysterious and sinister doctor. The actress returned to her theater roots in 2007 with the West End revival of “Boeing-Boeing” (1960), about a Parisian architect juggling three fiancées. Marsh reprised her acclaimed role of Rose on the 2010 revival of “Upstairs, Downstairs.” The three-part series began with her character running her own maid service in London, but only to return as head housekeeper to the same house where she previously served, after discovering a new family had moved in. Marshâ¿¿s return to “Upstairs, Downstairs” earned her a 2011 Emmy Award nomination for Outstanding Leading Actress in a Mini-series or Movie.

The above TCM Overview can also be accessed online here.

The telegraph obituary in 2025.

Jean Marsh, who has died aged 90, co-created the historical domestic drama Upstairs Downstairs, and starred as the parlourmaid Rose Buck, a role that bridged three decades in her acting career.

The show was the joint creation of Jean Marsh and Dame Eileen Atkins, a close friend and fellow actress who, like her, came from a working-class background. The feline, green-eyed Jean Marsh was then in her mid-thirties, out of work, almost penniless and of no fixed address.

The pair accepted a job as house-sitters in the south of France, where they colluded on possible scenarios for a television series that could depict the working classes fairly. “We still had giant-sized chips on our shoulders,” she recalled, and she was irritated by grandee roles. (“I’ve got the sort of facial bone structure that is supposed to make a good duchess. They never cast girls with fat faces as duchesses.”). They toyed with the idea of a drama focusing on the domestic staff of a household: “About that time, in 1967, The Forsyte Saga was on and we kept asking: ‘Who does the laundry in their house? Who does the cooking?’”.

Back in England, and despairing of any further progress, Jean Marsh called a television producer to pitch the idea. Within a few days London Weekend Television had signed up the series, and production began in less than three months, with Jean Marsh plundering Mrs Beeton’s Household Management for background. Master tapes spent almost a year in storage before finally being broadcast – in black and white – on October 10 1971. Soon, LWT executives realised that they had a hit on their hands.

Running for 68 episodes from 1971 to 1975, Upstairs Downstairs drew audiences of 30 million and was sold to 80 countries. In her role as Rose, plucky and generous head housemaid at 165 Eaton Place, Jean Marsh received an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress, and claimed to have been sent greater quantities of lustful fan mail “than the beautiful girls on the show”.

The series won two Baftas and a Golden Globe. There were spin-off novels, a spin-off television serial Thomas and Sarah (1979), a magazine and a cookbook. Gerald Clarke, of Time magazine, called it “the most exalted soap opera ever to be shown on TV”.

Jean Marsh was born on July 1 1934 in Stoke Newington, north-east London. Her mother, Emmeline, worked as a housemaid in a pub hotel; her father Henry was an outdoor maintenance man and printer’s assistant.

The family were creative and largely self-taught. Henry Marsh learnt to play the piano by ear, and when the young Jean fell ill with nervous paralysis, the parents enrolled her in ballet lessons as treatment. These were followed by classes in piano, singing and mime.

As she told The Guardian in 1972: “If you were very working class in those days, you weren’t going to think of a career in science. You either did a tap dance or you worked in Woolworths.”

She left school at the age of 15 and began working as a dancer for film. Her first onscreen appearance was in Happy Go Lovely (1951), and she was the principal dancer in Where’s Charley? (1952).

From 1956 she began a steady career in television, including a role as a robot in an episode of The Twilight Zone (1959), and co-starred alongside Laurence Oliver in the American television adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence (1959). That year she also made her Broadway debut in John Gielgud’s Much Ado About Nothing.

From 1965 she took various roles in Doctor Who: first as Princess Joanna of England in The Crusade, then as Sara Kingdom, a short-lived companion of William Hartnell’s Doctor who was clad in a “fabulously ridiculous” catsuit of tight-brown tweed, before being hit by a ray gun that aged her to death. In 1989 she returned opposite Sylvester McCoy as Morgaine, the chief villain in the Arthurian story Battlefield.

On the big screen, she put in a brief appearance as Octavia in Joseph Mankiewicz’s vast historical epic, Cleopatra (1963), starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

The hapless production proved so monumentally expensive that it made a loss despite grossing more than $50 million. Feelings ran high, and Jean recalled an atmosphere that was “so extravagant, so louche, it affected everyone’s lives. Richard and Elizabeth weren’t the only people who had an affair.”

Away from Upstairs Downstairs she secured a key role in Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972), as the secretary who finds her boss strangled to death. She negotiated a break from her contract with LWT to appear on the New York stage, in Alan Bennett’s Habeas Corpus (1975).

When Upstairs Downstairs finished later that year she returned to America, playing Gwendolen in The Importance of Being Earnest as well as the sophisticated lead – also called Gwendolen – in the West Coast premiere of Tom Stoppard’s Travesties (in repertory together, 1977), and opposite Tom Conti in Whose Life Is It Anyway (1979) on Broadway.

Despite the widespread popularity of Rose Buck, some of Jean Marsh’s most memorable work was in science fiction and fantasy. Return to Oz (1985) was a dark adventure film based on the work of L Frank Baum (creator of The Wizard of Oz), in which Jean played the dual role of a brutal psychiatric nurse and a witch with a detachable head.

For the effects-laden Willow (1988), directed by Ron Howard, she was enveloped in rubber latex and warts. Make-up took five hours a day and the dust and smoke machines gave her bronchitis, but she maintained that it was “huge fun. I used to walk down the street, and kids would run away from me.”

She and Eileen Atkins joined forces once again in 1992 for The House of Eliott, the story of two sisters in 1920s London who establish a dressmaking business. The following year Jean published her first novel, inspired by her work on the series, under the same title. Her later novels included Iris (2000), and Fiennders Abbey (2011).

In 2009 the BBC commissioned a revival of Upstairs Downstairs, to star Keeley Hawes and Ed Stoppard. The first episode aired at Christmas the following year, now set in 1936, six years after the original series had concluded.

Jean Marsh reprised her role as Rose Buck, with Eileen Atkins playing an “upstairs” character, the redoubtable Lady Maud Holland. Neither was involved on the scripts, and Eileen Atkins departed after the first series. In 2011, as the second series was due to begin filming, Jean Marsh suffered a minor stroke, curtailing her involvement on the show, which was subsequently cancelled.

She was an ardent Francophile, who would translate articles from Le Monde into English, then the next day translate them back into French, to see how far she had drifted from the original.

Jean Marsh married, in 1955, the actor Jon Pertwee. They divorced in 1960. Though she lived with Albert Finney and Kenneth Haigh, both actors, and was in a 10-year relationship with the director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, she never remarried.

Jean Marsh was appointed OBE in 2012 for services to drama.

Jean Marsh, born July 1 1934, died April 13 2025

Air mail tribute by michael lindsay hogg in 2025.

A Love Letter to Jean Marsh

The Emmy–winning British actress who co-created and starred in the hit TV series Upstairs, Downstairs was brave, deeply empathetic, and funny to the end

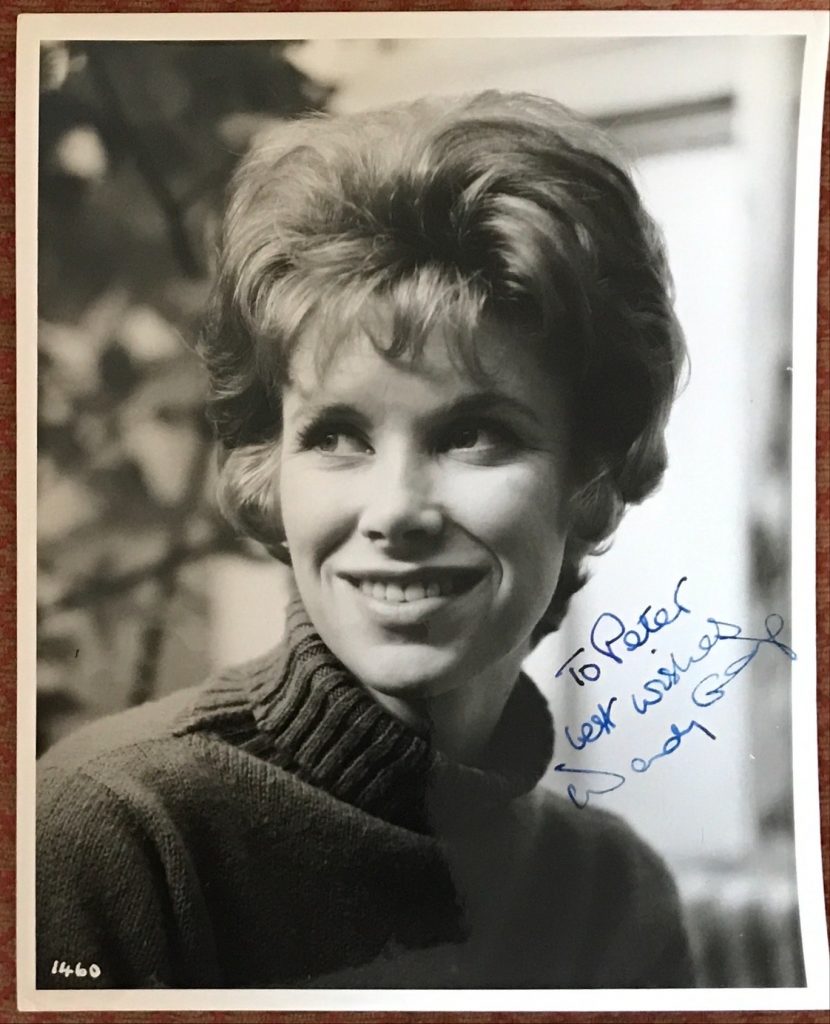

Iwas standing on Fifth Avenue in 1957, waiting for the light to change, when I saw on the other side of the street an English actor, Kenneth Haigh, then the toast of Broadway, starring in Look Back in Anger. Beside him was the prettiest girl I’d ever seen. Wearing glasses.

The light changed and we started to cross the street. The girl was slim and copper-haired. As we passed each other, going in different directions, we looked at each other for an instant. She had green eyes and a retroussé nose, and seemed very good-humored, as though the world was a fascinating place. If I could ever have a girlfriend like that, I thought, at the age of 16, I’d be happy

Ten years later, I was working in London and was asked to direct an episode of The Informer, a TV thriller, with the talented if drunken Ian Hendry, playing a private eye, and Jean Marsh, his girlfriend. She was the girl from Fifth Avenue. She still wore glasses.

When we were introduced and shook hands, we both felt we’d known each other forever. She said she liked my maroon chukka boots and gave me a punnet of strawberries for my birthday. I was 26 and she was 32.

After the TV series was complete, we met again at a lunch given on a Saturday afternoon. We went for a walk after around Mayfair. It was a sunny day, but the streets were almost empty. Just the two of us, it seemed.

We lived together for 12 years, and our friendship progressed, deepened, and never faltered—nor did our love—even though our lives did sometimes move in different directions, work, separation, and distance being the movers

Jean was born into a working-class family before World War II in Stoke Newington, then a rough London district. Her father, Harry, worked the night shift as a laborer at Odhams Press. He was a Communist, a vegan, and a voracious reader who wore thick National Health Service eyeglasses. Jean loved him dearly, partly because she knew his intelligence would never be put to proper use because of the straitjacket of the English class system.

Jean wore glasses most of her life and always voted Labour. Her mother, Emmeline, nicknamed “Poppy,” had been a barmaid and later a chaperone for theatrical children. She lived to be 102

Before being evacuated to the country with other children, Jean had survived the Blitz with rubble, bodies, and dust in the street as she went to school. She started working aged seven, as a dancer, to earn extra money for her family.

Her first film was The Tales of Hoffman, co-directed by the great Michael Powell, who she said was always nice to her. She was 15.

She and her best friend, the actress (and now dame) Eileen Atkins, created the very successful Upstairs, Downstairs, about a rich London family living in a grand house with a retinue of servants in the kitchen and attic attending to their every need—like Downton Abbey, but 40 years before. Jean won an Emmy in 1975, Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series, for playing the head maid, Rose Buck

She also wrote five novels, and was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire for her services to drama by Queen Elizabeth in a very grand ceremony at Buckingham Palace. A long way from Stoke Newington.

As things changed with time and circumstance, we still liked to be together, often going on holidays, and though living in different places, we spoke on the phone almost every day for 40 years. I think we missed each other.

Jean loved to cook—and to drink a glass of good red wine or two. Everywhere she lived, small or larger, was cheerful, bright, and welcoming. Once she became the first person in her family to own property, she bought a house for her mother and father and one for her sister. She was a whiz at crossword puzzles

Things could make her sad and she would cry, as when she told me on the phone that her friend, the fine actor Gordon Jackson, who played Hudson the butler in Upstairs, Downstairs,had died that afternoon in the hospital. As someone of instinctive grace, she despised snobbery and arrogance. She was brave when called upon to be.

Many men had crushes on her, perhaps even the somewhat older Graham Greene, one of the great writers of the 20th century. After a screening of Doctor Fischer of Geneva, the TV adaptation of his book that I’d directed, a few of us had dinner. He called the next morning to thank me, and asked, “Um, does Miss Marsh have a regular companion?”

Always slim, Jean loved to walk near her house in Oxfordshire—on paths, up hills, along the river. Guerlain Mitsouko was her favorite perfume. Street traders in Soho would treat her as one of their own, offering to “take care of things, Jean,” if anyone ever threatened her. She loved classical music and opera. And rock ’n’ roll

The women who looked after her in these last years loved her as she did them. She was always empathetic to those facing adversity, as she often had. Very intelligent, she thought things through herself, never relying on received opinion.

And she was very, very funny.

And I loved her