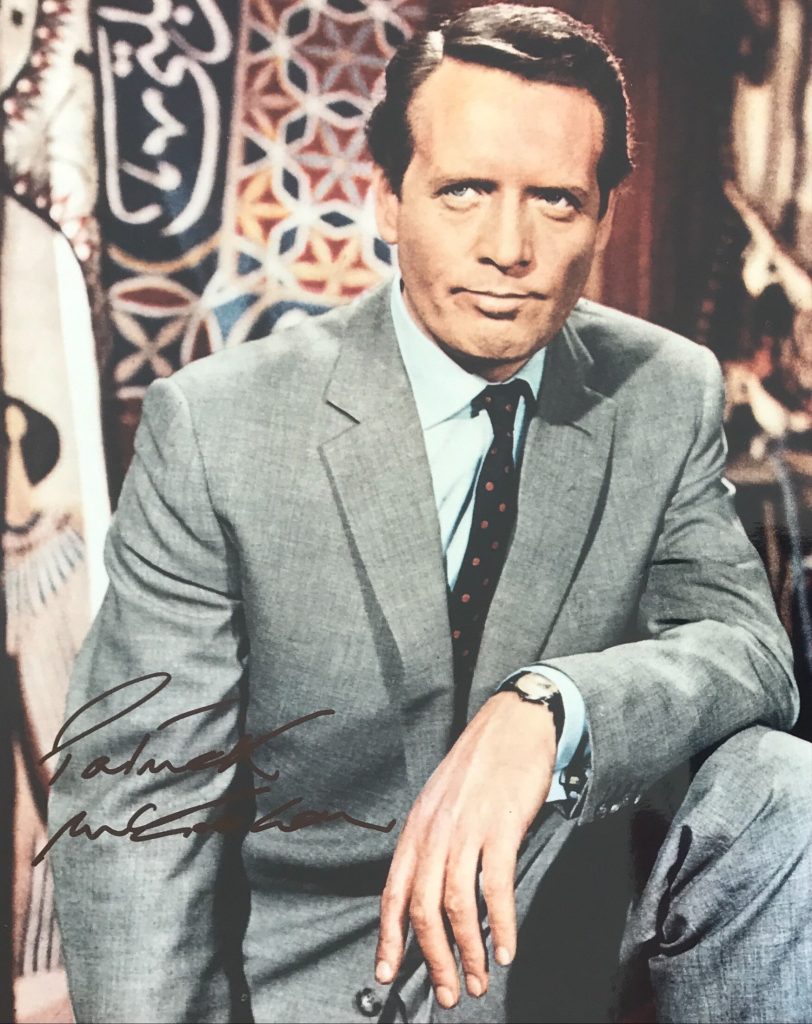

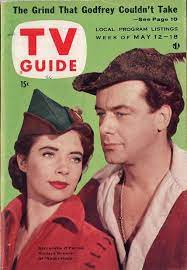

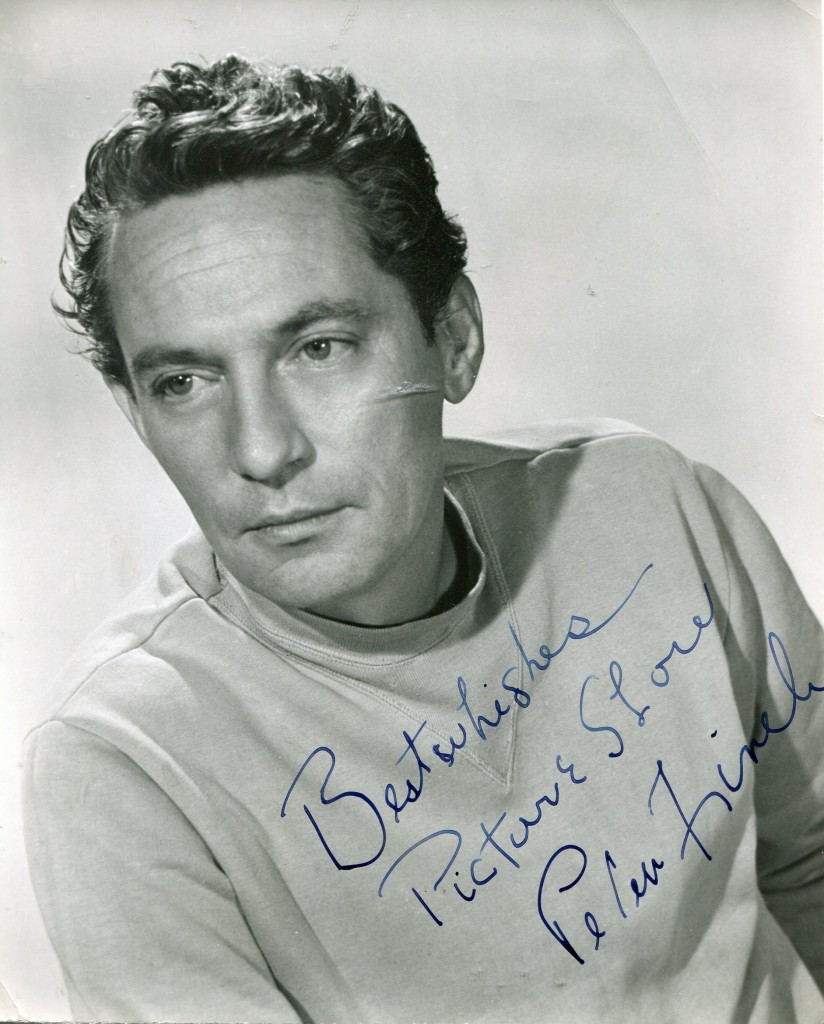

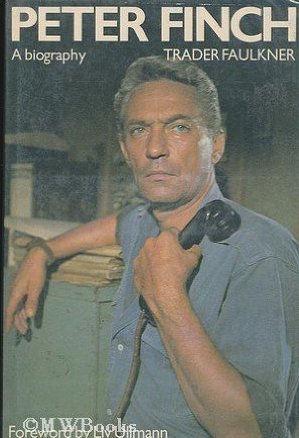

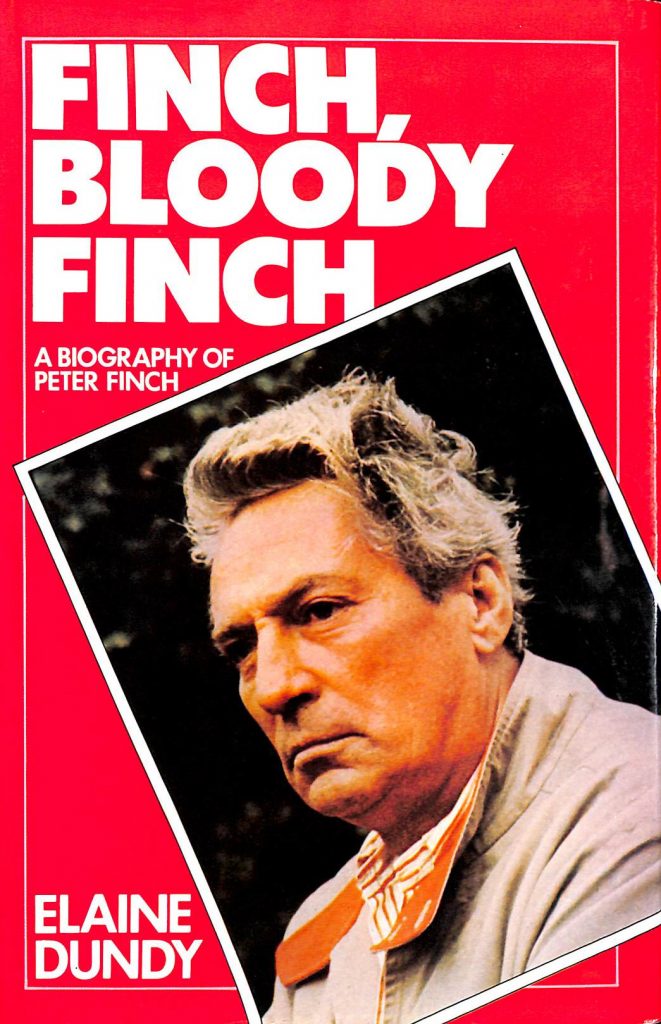

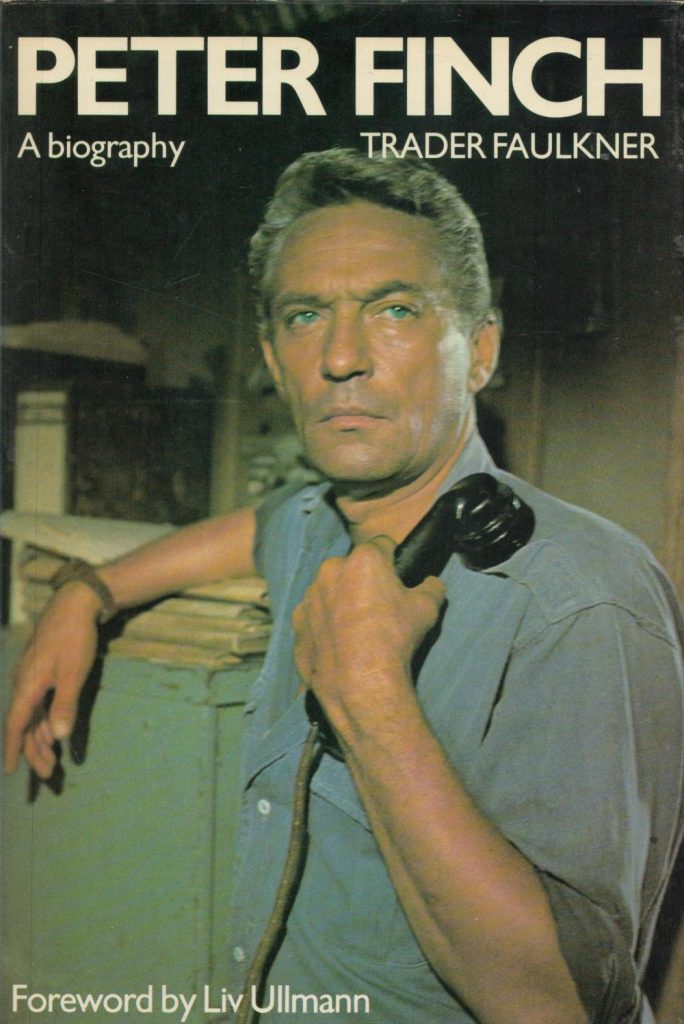

Peter Finch said once: ‘I’ve been lucky. My agent might have hoped that I’d be a bigger name – as they call it – in America but I’m very happy. I like what I do and I choose what I do’. He did not always choose wisely. He was marked for the heights of stardom when he made his forst film in Britain but for a while the real peaks eluded him – too many bad films and kiss of death, a long-term Rank contract.

In the right material he always looked good. He had a good actor’s voice and stance, a touch of arrogance, a touch of humour, some warmth, leading man’s looks and the same sort of gritty dependability that characterized the malestars of Hollywood’s golden age” – David Shipman’s “The Great Movie Stars- The International years”. (1972)

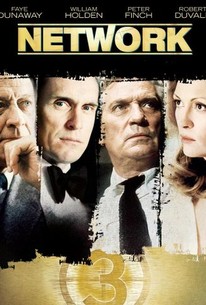

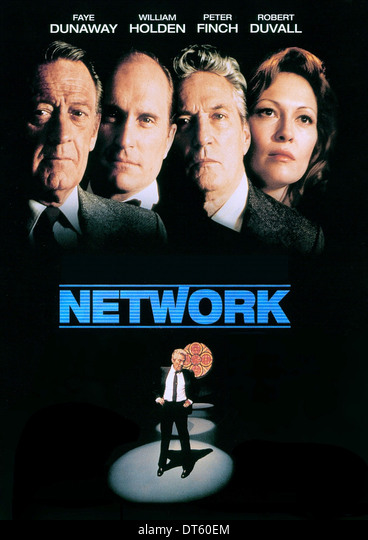

He won for his performance in “Network” in 1976. Peter Finch was born in London in 1916. He went to live in Australia when he was ten years of age. He made his first film in Australia in 1938, The film was entitled “Dad and Dave Come to Town”.

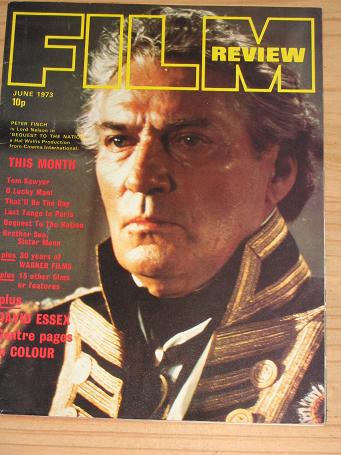

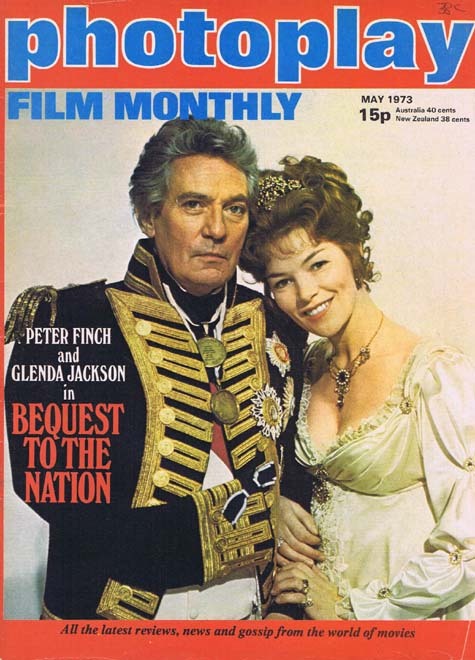

When Laurence Oliver and Vivien Leigh were touring that country with the Old Vic in 1948 they met Peter Finch and he was offered a role by Oliver in the play “Daphne Laureola” in London which he accepted.He made the film “The Miniver Story” in England and then went to Hollywood to make “Elephant Walk” with Elizabeth Taylor and Dana Andrews. Over the next few years he made many fine films including “A Town Like Alice”, “The Nun’s Story”, “The Girl With Green Eyes”, “No Love for Johnny” and “Far From the Madding Crowd”. He was enjoying the huge revival of his career when he died from a heart attack in 1977 at the age of sixty. Peter Finch was the first actor to win a Academy Award for Best Actor after his death

TCM Overview:

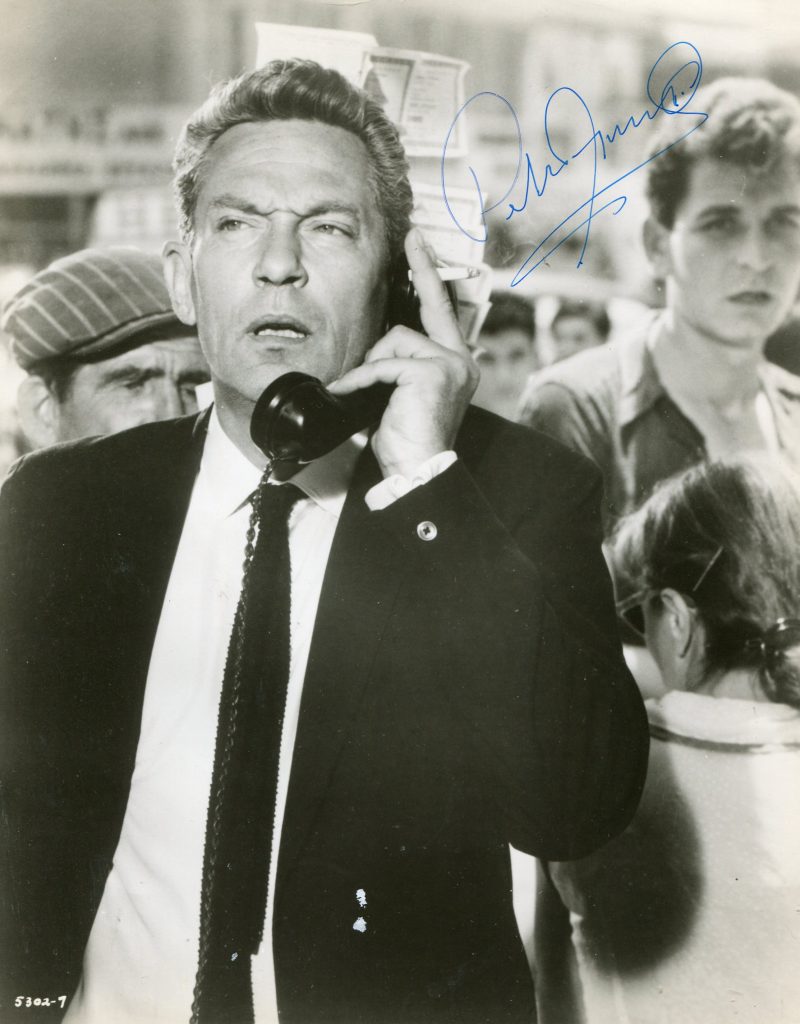

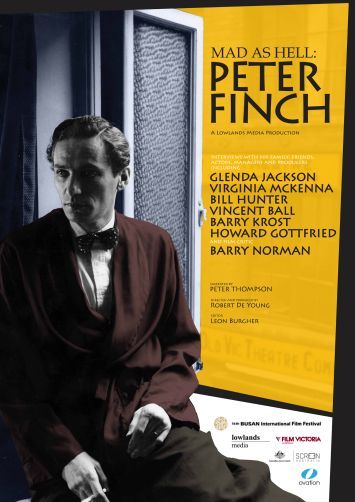

A former vaudeville performer and popular radio actor in Australia, Peter Finch transitioned to film in his native England, where he rose from supporting actor to leading man in a number of emotionally charged dramas. While he delivered more than a few notable performances in his four-decade career, Finch was forever identified as the raving mad prophet Howard Beale in “Network” (1976), whose line “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore!” remained one of the most identifiable in all of cinema history. After supporting roles in several British-made films, he made the Hollywood transition with “The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men” (1952) and starred opposite Elizabeth Taylor in “Elephant” (1954).

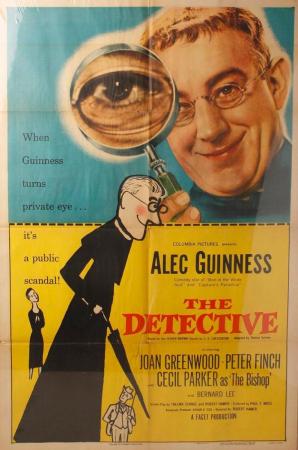

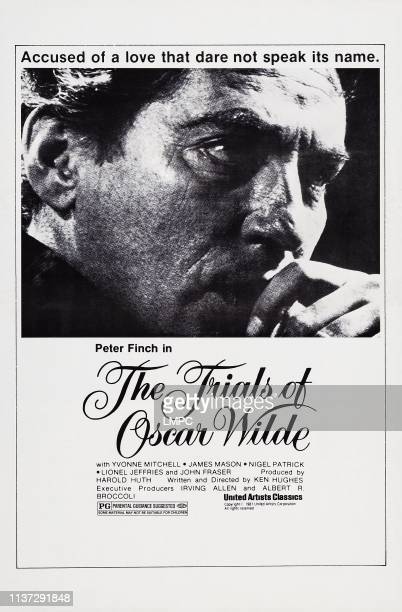

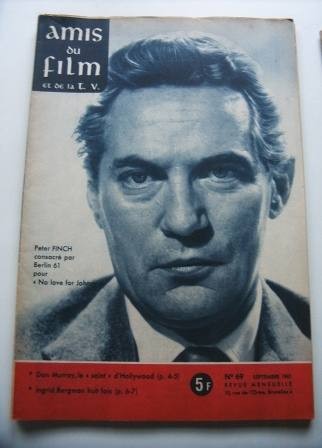

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Finch went back and forth between films made in Hollywood and England, earning award nominations along the way for his performances in “The Nun’s Story” (1959), “The Trials of Oscar Wilde” (1960) and “No Love for Johnnie” (1961). Some time passed before Finch delivered another noteworthy performance, this time earning acclaim for his sympathetic and non-clichéd turn as a gay man in “Sunday Bloody Sunday” (1971).

A few years later, he captured attention as the raving maniac Beale in “Network,” only to die from a heart attack two months before winning his one and only Academy Award, making him the first actor to win a posthumous Oscar.

Born on Sept. 28, 1916 in London, England, Finch was raised by his father, George, a research chemist from Australia who moved to England prior to World War I, and his mother, Alicia. His parents divorced when he was just two years old, leading to his father being given custody.

Decades later, Finch discovered that George was not his biological father and that his mother had carried on with an army officer named Wentworth Edward Dallas Campbell, leading to his parents’ divorce. After living for a time with his paternal grandmother in France, the 10-year-old was sent to live with his great uncle in Sydney, Australia.

After graduating from North Sydney Intermediate High School, Finch worked as a waiter, an apprentice on a sheep farm, and a copy boy for the Sydney Sun, but soon felt the pull of stage acting. He began appearing in sideshows and vaudeville, even serving as a stooge for American comedian Bert le Blanc before touring Australia with George Sorlie’s traveling company.

It was with Sorlie’s troupe that gained Finch notice with a producer from the Australian Broadcasting Commission, who served as his mentor and cast him in a children’s radio series. At the time, he also made his feature debut in “Dad and Dave Come to Town” (1938), which led to a more substantial part in the crime drama “Mr. Chedworth Steps Out” (1939). But with the world on the brink of war, Finch’s acting career was put on hold in order for him to enlist in the Australian army in 1941.

He served for a time in the Middle East and participated in the Bombing of Darwin as an anti-aircraft gunner, though he did continue to perform by appearing in the wartime propaganda film “The Rats of Tobruk” (1944), and directing plays for tours of army bases and hospitals. Following his discharge with the rank of sergeant in 1945, Finch established himself as one of Australia’s premiere radio actors and went on to co-found the Mercury Theatre Company with fellow actors Allan Ashbolt, Sydney John Kay, Colin Scrimgeour and John Wiltshire.

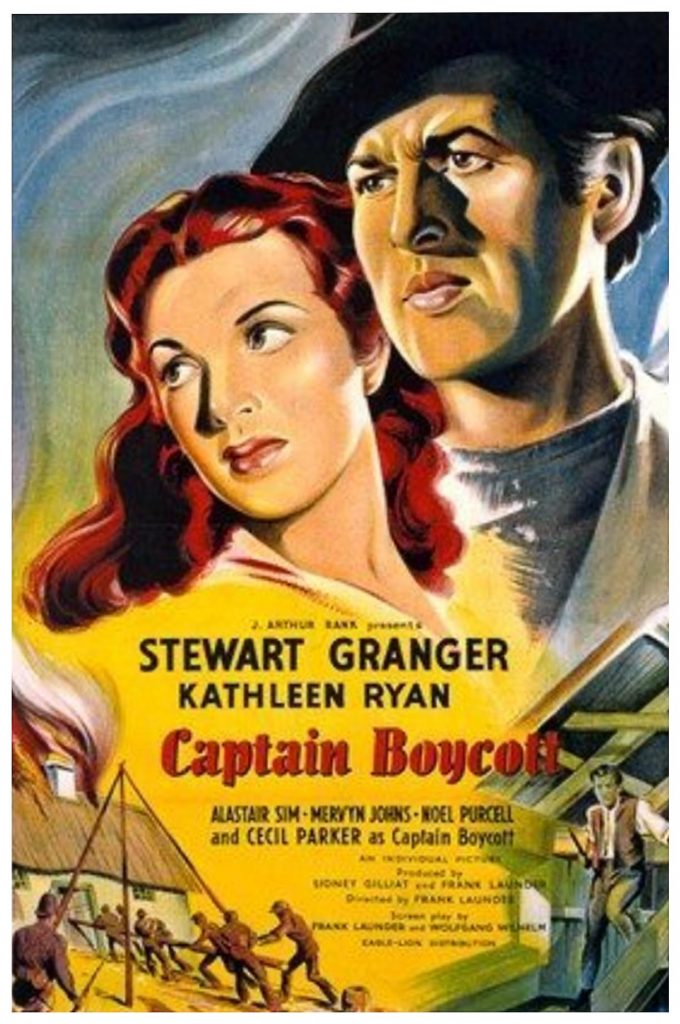

Named after Orson Welles’ own company, the Mercury put on a number of notable plays, including “The Imaginary Invalid” (1948), which starred Finch and attracted the attention of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, who later invited the actor to London. He returned to films with supporting roles in British productions like “Train of Events” (1949), “Eureka Stockade” (1949) and “The Wooden Horse” (1950), before making the turn toward Hollywood films.

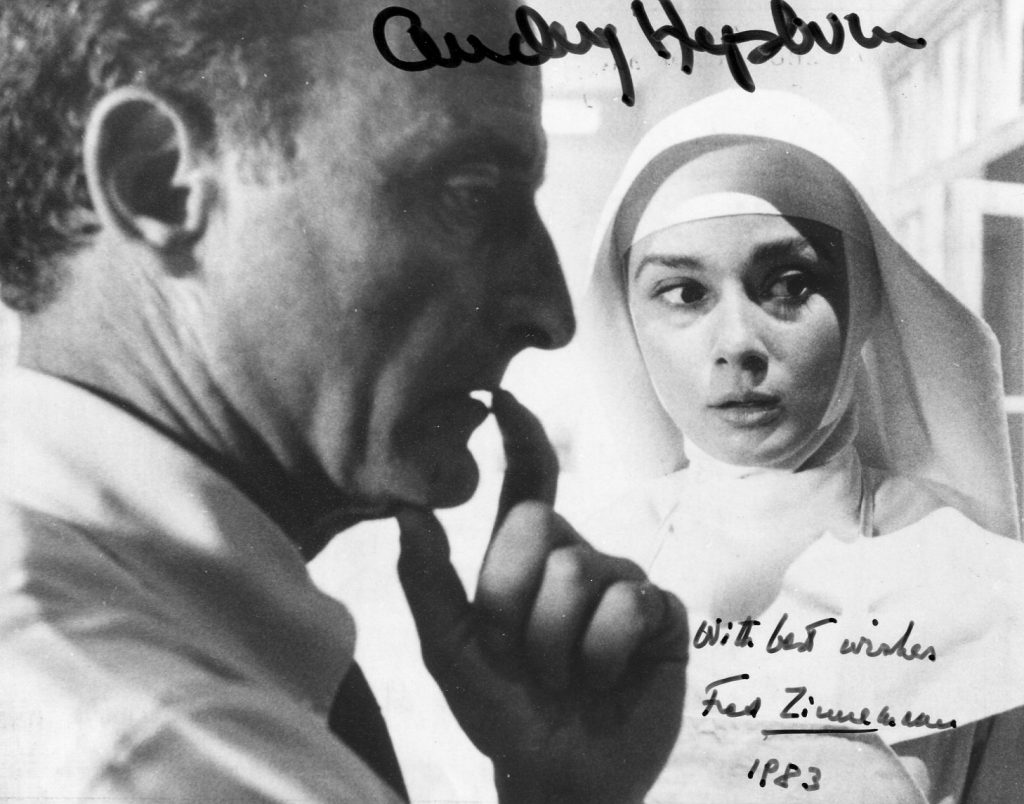

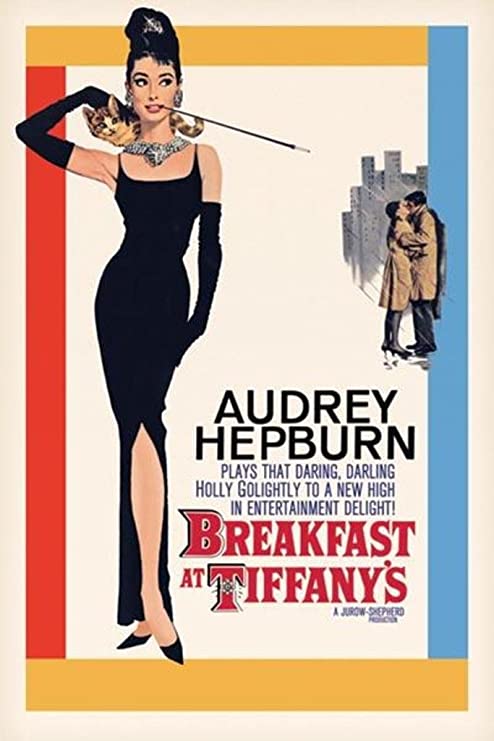

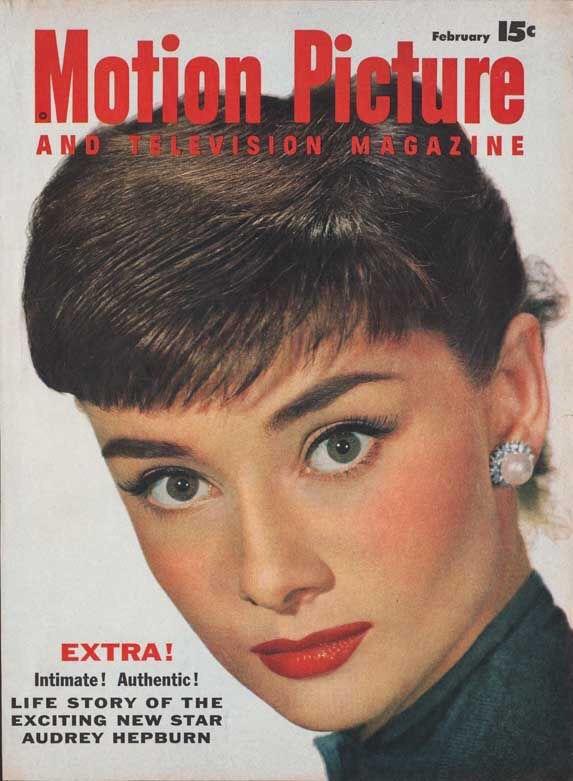

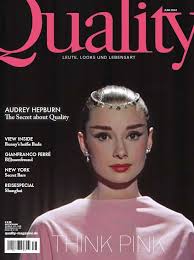

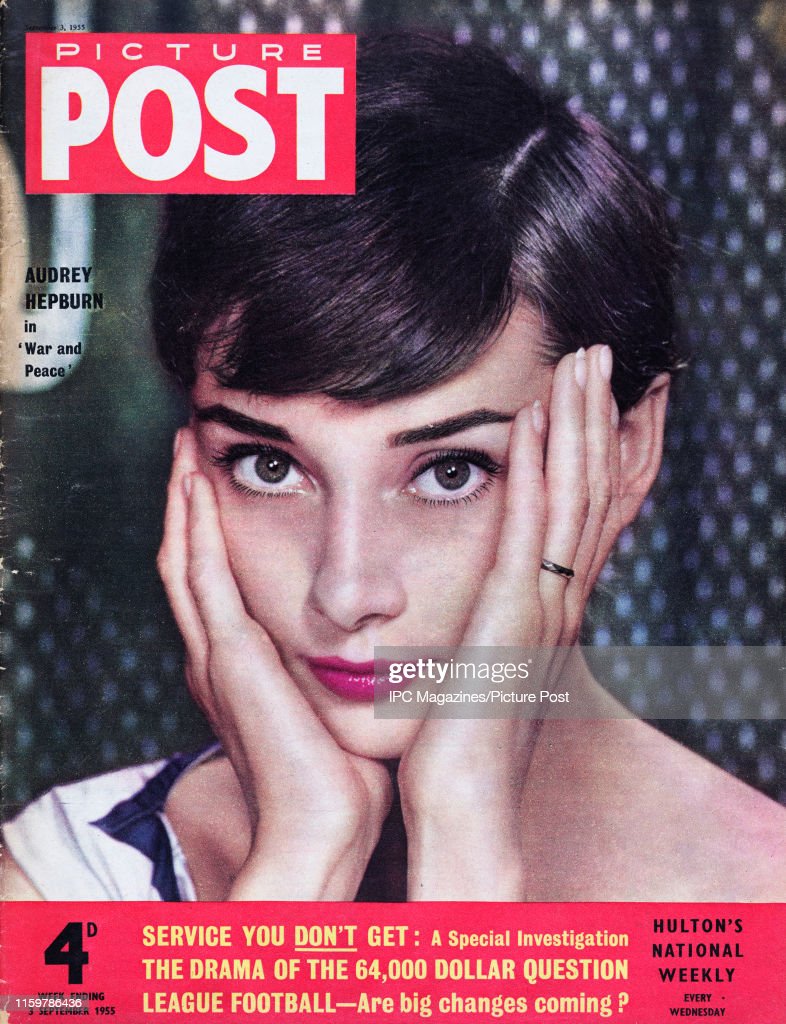

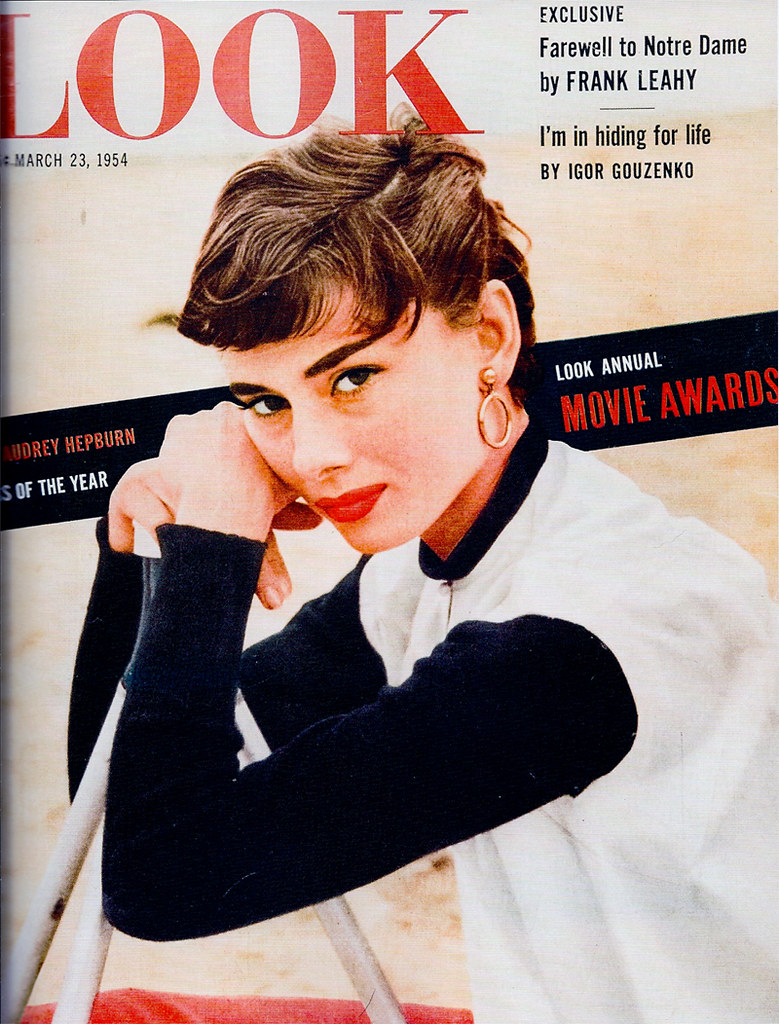

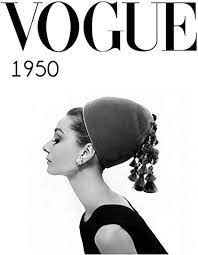

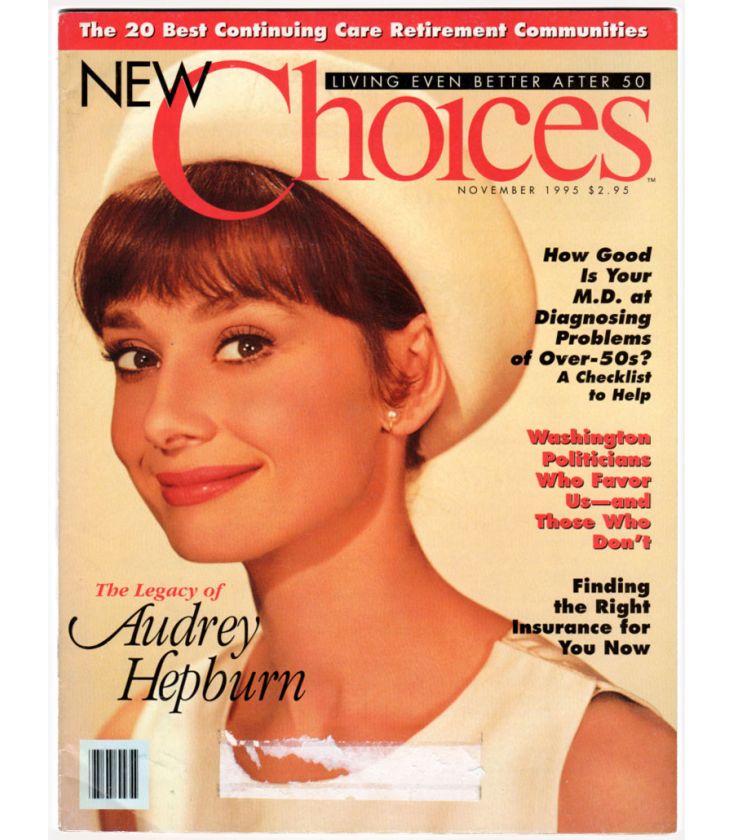

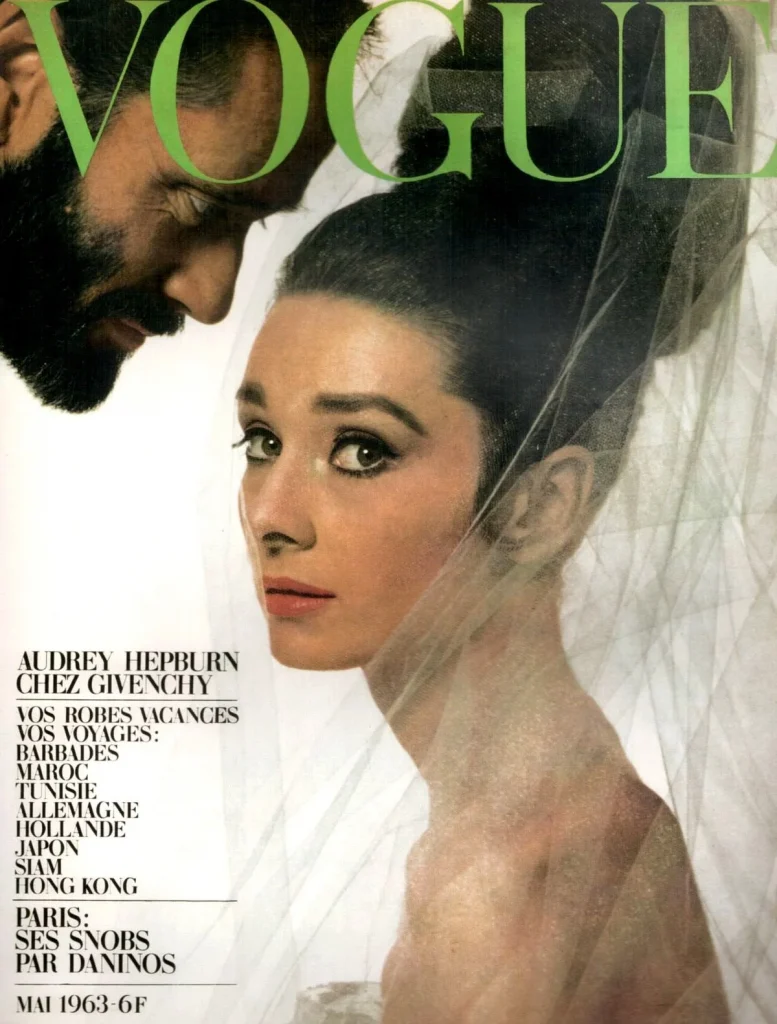

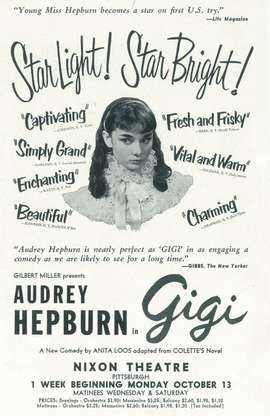

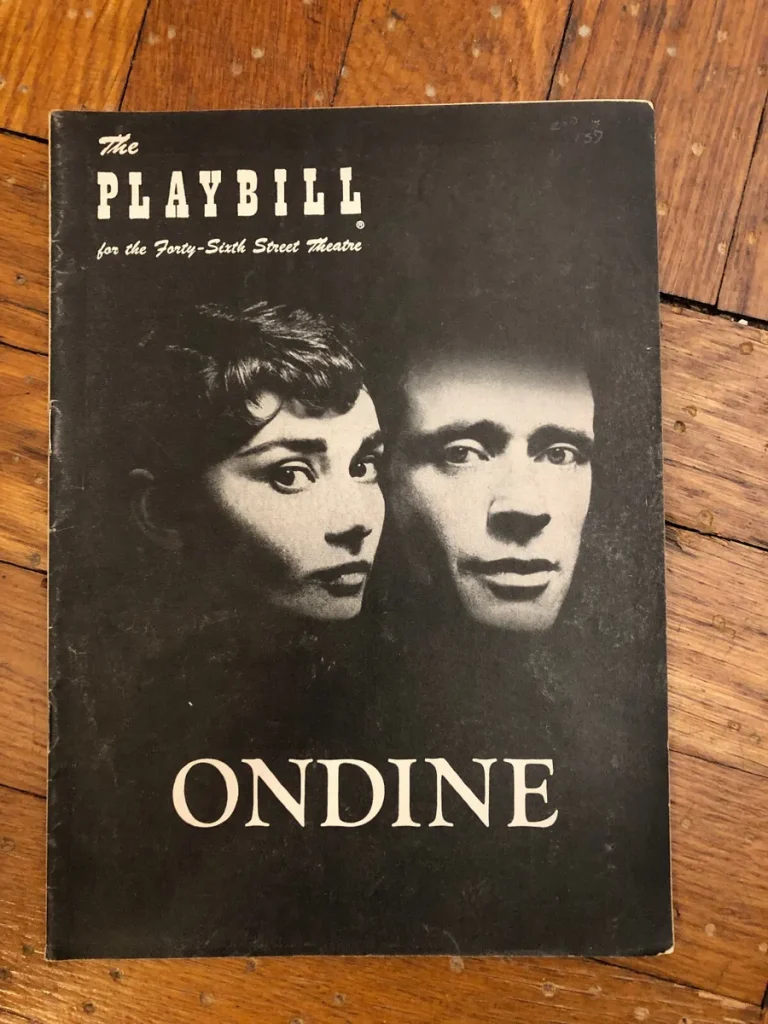

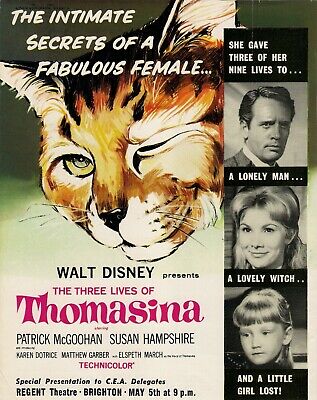

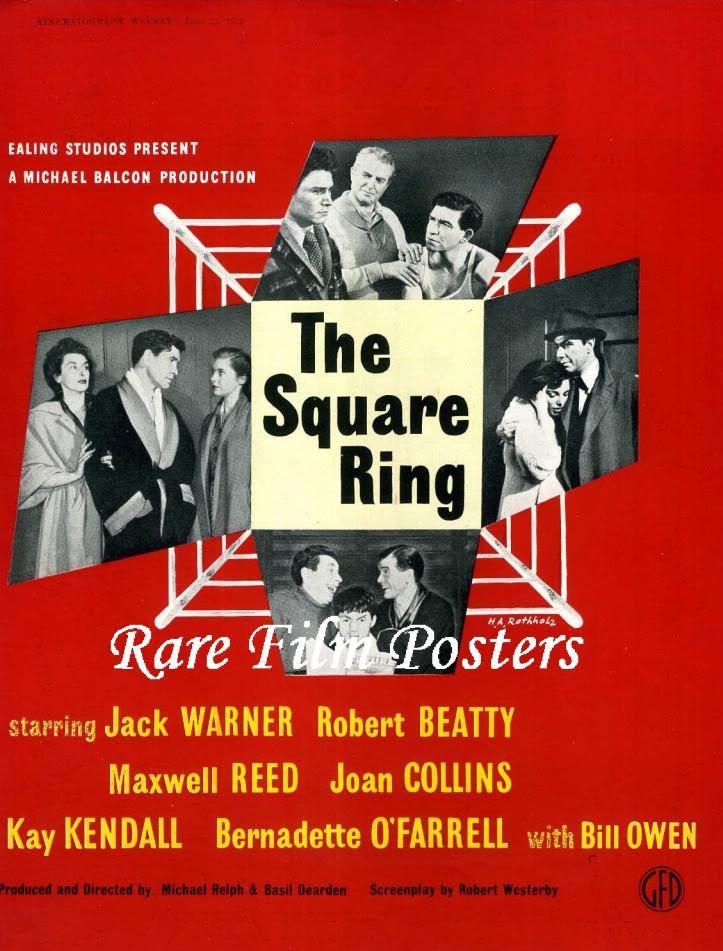

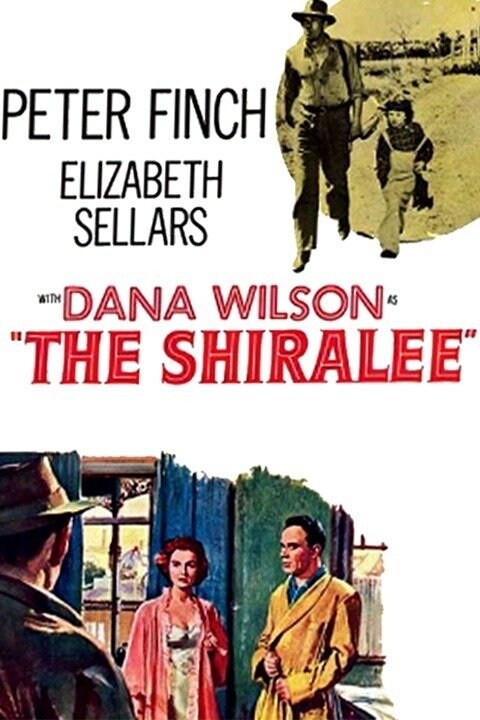

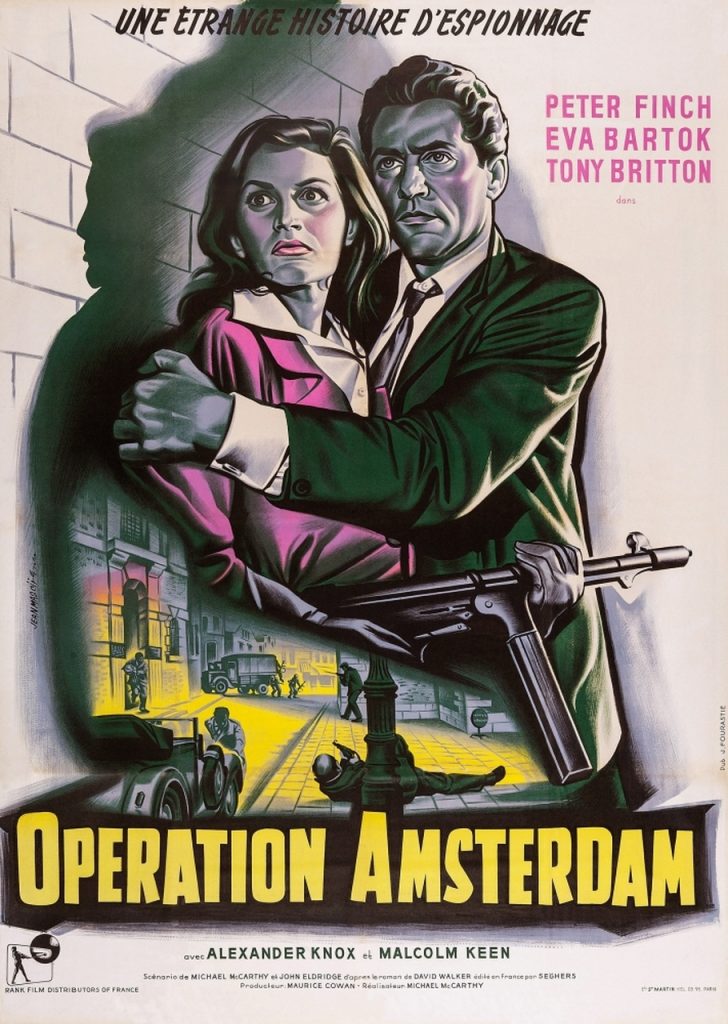

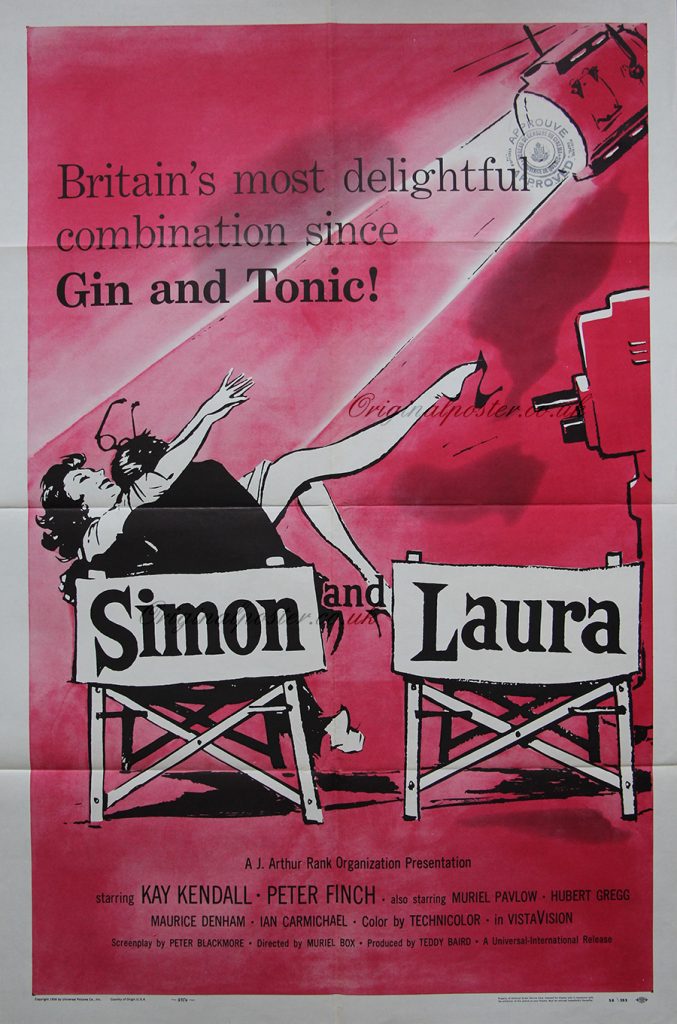

He played the Sheriff of Nottingham in “The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men” (1952) and starred opposite Elizabeth Taylor – who took over for an ailing Vivian Leigh – in the rather disappointing melodrama “Elephant Walk” (1954). His career took off as he approached middle age in the mid-1950s with films including the charming romantic comedy “Simon and Laura” (1955), “The Dark Avenger” (1955) co-starring Errol Flynn, and the somber war drama “A Town Like Alice” (1956). In “Robbery Under Arms” (1957), he played famed cattle thief Captain Starlight, while he earned critical acclaim and a BAFTA nomination for his turn as a crusty surgeon working with an attractive nun (Audrey Hepburn) in the Belgian Congo in “The Nun’s Story” (1959).

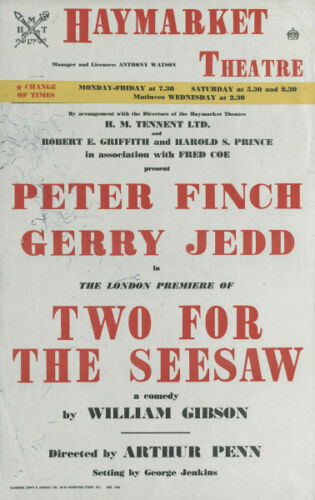

Finch was somewhat less busy during the 1960s, but early in the decade he delivered to acclaimed, award-winning performances, playing the title roles in the biopic “The Trials of Oscar Wilde” (1960) and the Parliament-set drama “No Love for Johnnie” (1961). Both roles earned him BAFTA Awards for Best Actor. He next starred opposite Jane Fonda and Angela Lansbury in the drama about marriage and infidelity, “In the Cool of the Day” (1963), before playing the third husband of a restless Anne Bancroft in the domestic drama “The Pumpkin Eater” (1964).

After starring in another relationship drama, “Girl With Green Eyes” (1964), Finch had a supporting role as a captain in the action yarn “The Flight of the Phoenix” (1965), starring James Stewart, and settled into a series of smaller films like “Judith” (1966), “Far from the Maddening Crowd” (1966), “The Legend of Lylah Clare” (1968) and “The Red Tent” (1969). He went on to deliver a powerful performance as a homosexual doctor engaged in a love triangle with Murray Head and Glenda Jackson in “Sunday Bloody Sunday” (1971), a revolutionary drama for its frank and rather sympathetic perspective on homosexuality. His performance as the well-adjusted doctor seeking escape from his repressed upbringing earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor.

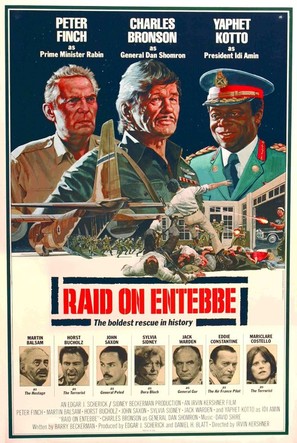

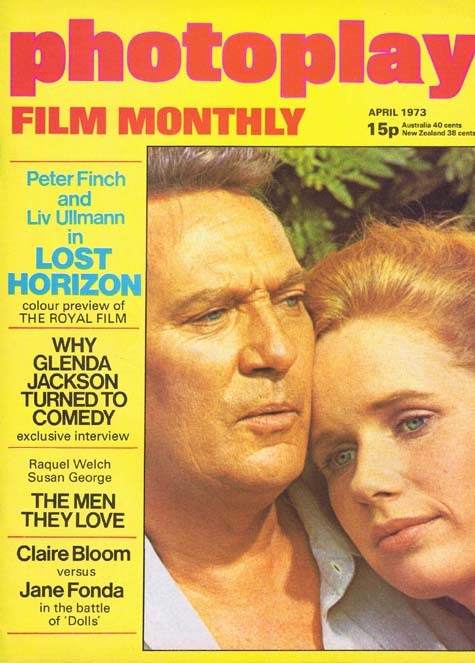

After his Oscar-worthy performance in “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” Finch starred in a string of mediocre films like “Shattered” (1972), a psychological drama about the disintegration of a man’s life due to alcohol and a bad marriage, and “Lost Horizon” (1973), a disastrous remake of Frank Capra’s 1937 original of the same name. After playing real-life Cardinal Azzolino in “The Abdication” (1974), Finch played the one character that he would forever be indentified with, TV news anchor Howard Beale, the Mad Prophet of the Airwaves whose mental breakdown on live television leads to a ratings bonanza for a struggling upstart station in Sydney Lumet’s searing satire, “Network” (1976). Also starring William Holden, Faye Dunaway and Robert Duvall, the film was a major critical and commercial hit, and received 10 Academy Award nominations. But just two months before the Oscar ceremony, on Jan. 15, 1977, Finch suffered a fatal heart in the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel, where he was waiting to meet Lumet for breakfast. He was rushed to the UCLA Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead hours later. Finch was 60 years old. At the ceremony, he won the Oscar for Best Actor, which was accepted by “Network” writer Paddy Chayefsky and Finch’s third wife, Eletha Barrett. Soon after, he was posthumously nominated for an Emmy Award for his performance as Yitzhak Rabin in the television movie, “Raid on Entebbe” (NBC, 1977), which aired days before he died and was the last time Finch was seen on screen.

By Shawn DwyerThe above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Blog on Peter Finch in “Pop Matters” can be accessed here.