Wikipedia entry:

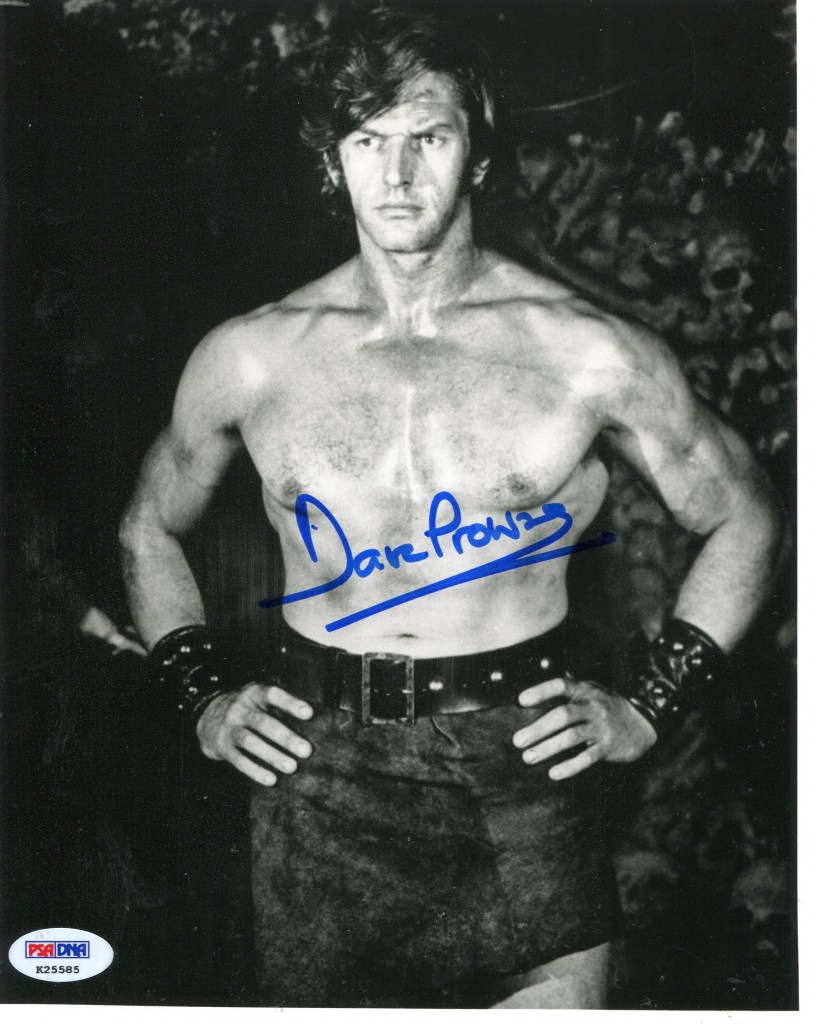

David Prowse, MBE (born 1 July 1935) is an English bodybuilder,[1] weightlifter and actor. He played Darth Vader in the original Star Wars trilogy, though the character’s voice was provided by James Earl Jones. He also played the Green Cross Code man, a character used in British road safety advertising.

Within the United Kingdom, Prowse is also well known as the Green Cross Code Man, a superhero invented to promote a British road safety campaign for children in 1975. As a result of his association with the campaign, which ran between 1971 and 1990, he received the MBE in 2000.[16]

He had a role as F. Alexander’s bodyguard Julian in the 1971 film A Clockwork Orange, in which he was noticed by the future Star Wars director George Lucas.[17] He played a circus strongman in 1972’s Vampire Circus, a Minotaur in the 1972 Doctor Who serial The Time Monster, and an android named Copper in The Tomorrow People in 1973. He appeared in an episode of Space: 1999, The Beta Cloud in 1976 right before he was cast as Darth Vader. Around that time, he appeared as the Black Knight in the Terry Gilliam film Jabberwocky (1977).

He had a small role as Hotblack Desiato‘s bodyguard in the 1981 BBC TV adaptation of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. He appeared in the first series of Ace of Wandson LWT and as a bodyguard in Callan. He played Charles, the duke’s wrestler, in the BBC Television Shakespeare production of As You Like It in 1978. Prowse played Frankenstein’s monster twice, in The Horror of Frankenstein and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell.

Prowse made two uncredited appearances on The Benny Hill Show. On Hill’s first show for Thames Television in 1969, he played a briefs-clad muscleman in the “Ye Olde Wishing Well” quickie, and in 1984 he showed off his muscles in a sketch set to the song “Stupid Cupid”. The earlier routine was also featured in the 1974 film The Best of Benny Hill, in which he was credited. Amongst his many non-speaking roles, Prowse played a major speaking role in “Portrait of Brenda”, the penultimate episode of The Saint broadcast in 1969.

In May 2010, he played Frank Bryan in The Kindness of Strangers, an independent British film produced by Queen Bee Films. The film screened at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. Prowse was brought up on the Southmead housing estate in Bristol, winning a scholarship to Bristol Grammar School. Prowse attended Bristol Grammar School. In his teens, Prowse was 6 feet 6 inches (198 cm) tall, and developed an interest in bodybuilding. His early jobs included a bouncer at a dance hall, where he met his future wife, and a lifeguard at Henleaze Swimming Pool. Following his successes from 1961 in the British heavyweight weightlifting championship, he left Bristol in 1963 to work for a London weightlifting company.Prowse has been married since 1963 and is the father of three children.[20] He is a prominent supporter of Bristol Rugby Club.