Charlie Drake was a very popular English comedian who had a TV following before a cinema career opened up for him. He was born in 1925 in Elephant and Castle, South London. His first TV series was “Laughter in Store”. His starred in four movies “Sands of the Desert” in 1960, “Petticoat Pirates” with Anne Heywood, “The Cracksman” with George Sanders and Nyree Dawn Porter and “Mister Ten Percent” in 1967. He died in 2006.

Denis Gifford’s “Independent” obituary:

Charlie Drake’s first joke – “A little boy had a tooth out and asked the dentist if he could keep it. Why? I want to take it home, put some sugar on it and watch it ache!”

Actually it wasn’t Charlie Drake’s joke, it was Max Miller’s. He heard it on the wireless. And he wasn’t Charlie Drake, anyway. He was Charles Edward Springall, age nine. Drake came much later, borrowed from his mother, the former Violet Drake. Like many comedians, if not all of them, Charlie Drake began with jokes borrowed from others, but once his real career in comedy got under way via television, he became the most original slapstick comedian in the country, easily out- slapping those few who had attempted visual comedy in the silent film era.

Born in Elephant and Castle, London, in 1925, the son of a newspaper seller who took racing bets on the quiet, little Charlie was only eight when he answered an advertisement in the South London Press and was first in the queue to audition for the great top-of-the-bill coster comedian Harry Champion. He sang that master’s most popular hit, “Boiled Beef and Carrots”, and promptly won a place in the choirboy chorus backing the star in his grand finale, “Any Old Iron” (pronounced “I-hern”). His reward: a six-day booking for half a crown (12 1/2p).

No further bookings ensued, so young Charlie augmented his non-existent pocket money doing a pre-school paper round and a post-school apprenticeship to a cats-meat man (tuppence a stick-ful). His education was at the Victory Place Junior School where the only prize he won was for Scripture: he was able to name Mary’s husband. Moving up to Paragon Row Seniors he read the “Just William” books and formed a William-style Secret Society called the Red Hand Gang. Show business struck again when he did a deal with the manager of the Elephant and Castle Picture Palace: in return for winning the ten-shilling (50p) prize at every amateur talent contest, he slipped the manager five bob (25p).

Drake was 14 when he left school, in the summer of 1939; he also left home. He became an electrician’s mate, the first of innumerable jobs, all of which would find their way into his television and later film situations. By night he was an Air Raid Precautions messenger boy. He devised his own way to extinguish incendiary bombs: old ladies’ knickers stuffed with sand. Then he joined the Naafi as a baker. His fruit cakes were famous until he was sacked for using too many rationed currants.

He tried for proper war service and was instantly rejected by the Navy. He was only 5 feet 1 1/2 inches tall. “I was raised on condensed milk,” he explained. He volunteered for the Royal Air Force and was, surprisingly, taken on and trained as a rear gunner. “I was the right size for the little turret.” He promptly put in for all the services shows he could – Ralph Reader’s “RAF Gang Show,” Ensa, “Airmen in Skirts” – and was rejected by them all. But one useful thing happened: while training in Northern Ireland he met an oversize pilot named Jack Edwardes, who would in time become Drake’s first partner on television. Drake’s main active service was in India, where he caught dysentery and became the only airman who needed to have his shorts shortened.

On demob Drake formed his first double act with a friend called Sidney Cant. They sang “She’s Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage” at the King’s Arms pub at the Elephant. Unable to afford the tram fare, Drake walked up West every night to watch the big star comedians leaving their stage doors.

After failing his first BBC audition for Workers Playtime – he did his half-hour act in the wrong studio so the producer never saw him – he changed his name to Charlie Smart and won a provincial variety tour opening the show wearing a white trilby and a brown-and-red check suit. His first broadcast came from this, and he sat up all night writing 200 fan letters under 200 assumed names, posting them to Broadcasting House. They all came back to him unopened.

Somebody told him that Charlie Smart was the name of a popular broadcasting organist, so once again he changed his name. This time he came up with a permanent winner, Charlie Drake. Unfortunately it didn’t help his career: he failed to pass his first audition at the Windmill Theatre – and failed a further six times. He found steadier work in the summer of 1953 as a Butlin’s Redcoat. He taught campers ju-jitsu and boxing, he called bingo, he clowned for the kiddies, and he stole £60 a week from the bingo take. At the end of the season Billy Butlin himself sacked him, and said he knew all along about the thefts, but had kept him on as his one and only ju-jitsu coach.

Deciding to try his luck with an agent, Drake now joined Phyllis Rounce, and at her office re-encountered Jack Edwardes, also looking for comedy work. His 6ft 3in height – 1ft 1 1/2in taller than the diminutive Drake – looked funny before they even started, and Rounce immediately got them a date at the Stage Door Canteen. They did a table tennis act which made the services audience roar. Several guest spots on BBC Children’s Television followed; the comic career of Charlie Drake was under way.

Michael Westmore, head of BBC Children’s TV, absconded to the newly formed ITV for London, Associated-Rediffusion, and took with him Drake and Edwardes. Drake was to devise and script an afternoon series for the double act. He called their characters “Big Jack and Little Mack”, but Westmore renamed them “Mick and Montmorency”.

The show was christened Jobstoppers and started on 30 September 1955. Every week the slap-happy pair tried their hands at a different job, and each week the show began with “Hello, my darlin’s!” and concluded with the cry of “It’s teeee-time!” Within weeks Drake had created two new national catch-phrases, among the young viewers at any rate. And to crown his success, TV Fun, the small screen’s answer to Radio Fun, starred them in a full-page strip drawn by the comic’s best cartoonist, Reg Parlett.

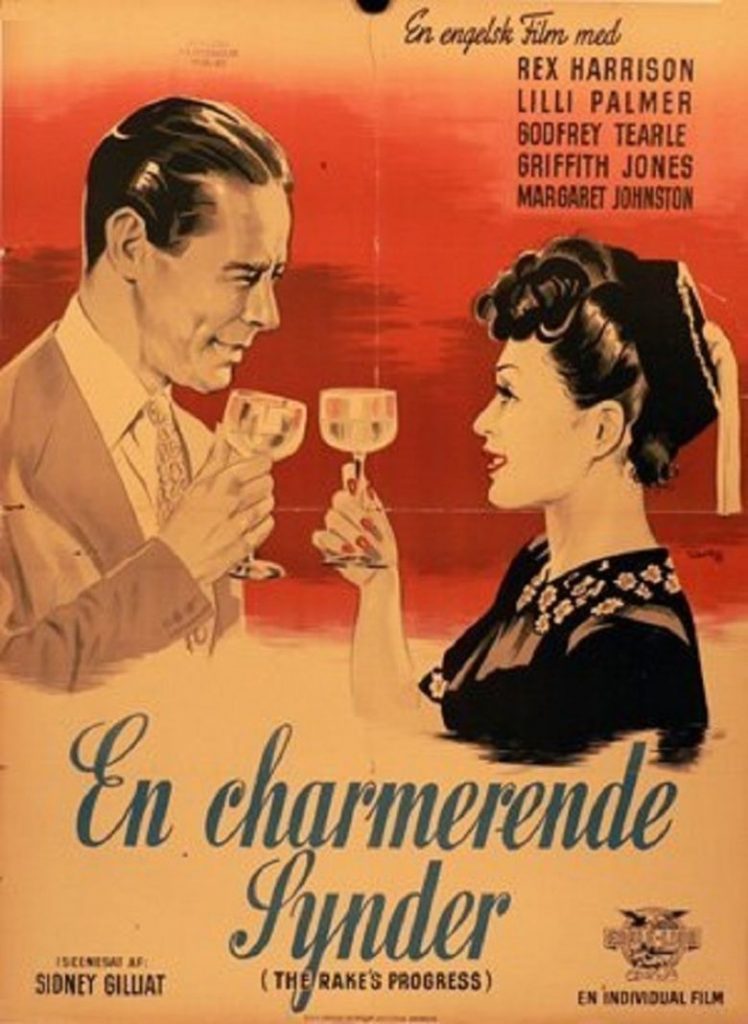

Ronnie Waldman, formerly the king of radio’s “Puzzle Corner”, now head of Light Entertainment at BBC Television, sat up and took notice. He offered Drake a one-off try-out in grown-up time and the half-hour Laughter in Store (3 January 1957) was such a slap-bang success that a full-blown series of six started on 6 May. Satisfyingly entitled Drake’s Progress (he would later use it as the title of his 1986 autobiography), the show was devised and co-written with him by the very professional George Wadmore, and was given the excellent supporting cast of Irene Handl, Warren Mitchell and the rotund Willoughby Goddard. Sadly the tall stalwart Jack Edwardes was nowhere to be seen. That particular partnership had been suddenly dissolved.

This was the first sign of what most people would call a basic flaw in Drake’s character, a supreme ego that put himself first in everything he did. It was once common among the great comedians (Charlie Chaplin, for example) but it takes more than supreme self-confidence to win in this age of television. No sooner had Drake been granted a second series of Progress, and been awarded a fresh team of writers in Sid Green and Dick Hills (who would prove their worth in scripting for Morecambe and Wise), than he demanded a showdown with Ronnie Waldman, the sacking of Green and Hills, and the right to be solo scripter of his own series. Drake won.

Drake’s television career now shot ahead in series after series, each show centralising on a classic slapstick sequence which, as was typical of the time, was performed live. For 10 years the title of the show was, simply, Charlie Drake, except for a brief sojourn at ATV in 1963 when it was called The Charlie Drake Show. The formula was always the same, with Drake trying his hand as an overalled workman in a different job each week. The slapstick climax would never be bettered until pre- filming became possible for Michael Crawford’s Some Mothers Do Have ‘Em, the only series comparable.

The climax to all this slapstickery came in 1961 with “Bingo Madness”, an episode which closed with Drake thrown through a bookcase, then out of a window, and crashing through a door. The camera panned down: there was Drake unconscious on the floor. Rushed to hospital, he was in a coma for days. The series was cancelled and Drake missed his first invited appearance at the Royal Variety Show. All would end well; in time he would star in no fewer than nine royal shows. And, when colour television arrived on BBC2 in 1968, his series would win the Golden Rose of Montreux.

Television led to many a stage show and pantomime. His first was as the King of Tyrolia in Sleeping Beauty at the Palladium. Co-stars were Bruce Forsyth and Bernard “I Only Arsked” Bresslaw. In the No 1 dressing room for the first time in his life, Drake complained and demanded that it be redecorated. It was; that was 1958. Much later, in 1974, another panto would be his big downfall. This was Jack and the Beanstalk at the Alhambra, Bradford. Drake wanted a local girl in the cast. The actors’ union Equity objected. The management paid her to leave. Equity fined Drake £760. He refused to pay, was suspended, banned from all provincial theatres, and found himself out of work for a year.

Drake was luckier in films. Associated British signed him up for several Technicolor extravaganzas. First came Sands of the Desert (1960) directed by the comedy specialist John Paddy Carstairs. A pretty newcomer, Sarah Branch, co-starred with a bunch of British “foreigners”: Peter Arne, Peter Illing, Harold Kasket, Eric Pohlmann, and many more. Drake was the travel agent who thwarted the wicked sheikh and opened a holiday camp in the desert.

Then came Petticoat Pirates (1961) directed by David Macdonald, who once did more serious stuff. Drake, playing under his own name, was a stoker whose ship is taken over by a group of renegade women led by Anne Heywood (ex Violet Pretty). The Cracksman (1963) came next, made in CinemaScope. Peter Graham Scott directed Drake as a jailed locksmith stealing gems from a museum. George Sanders, surprisingly, co-starred, with the TV favourite Nyree Dawn Porter as the girl. Mister Ten Per Cent (1967) was the last Drake feature proper, with Scott directing again and some pretty ladies: Annette Andre, Una Stubbs and Joyce Blair to name a few. Drake played Percy Pointer, a builder who writes a dramatic play that succeeds as a comedy.

His last films were a series for the Children’s Film Foundation entitled Professor Popper’s Problems (1975), directed by Gerry O’Hara. This set of six shorts was the only time he did not write or co-write the screenplays. The main plot point was that he invented the shrinking pill.

After several very big successes with records, most notably the hilarious “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” (produced by the brilliant George Martin), Drake’s best ever television series came in 1978. This was ATV’s The Worker with Drake back in his old character of the willing but useless handyman who will try anything and fail at everything. He sang the signature song, which was based on the music-hall queen Lily Morris’s long-lost hit “He’s Only a Working Man”. Lew Schwartz wrote, Alan Tarrant directed, and Henry McGee played the manager of the Labour Exchange, Mr Pugh (“pronounced Poo!”). McGee, a brilliant comic actor, was later acclaimed by Drake as his “closest and dearest friend”.

Suddenly Drake turned away from slapstick and comedy. He played Smallweed in the BBC TV serialisation of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1985). He played Ubu Roi in Spike Milligan’s variation of Alfred Jarry’s play, directed by Charles Jarowitz. He was in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1988), and in Samuel Beckett’s Endgame (1992) he was Nagg. He even won a Drama Award for his role as Davies in Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker (1983).

Drake’s extraordinary career was recognised rather too early by Eamonn Andrews in This Is Your Life back in 1961. The extremes of his personality are perhaps best shown in two opposing quotes. When he won the Golden Rose of Montreux he said, “I was voted the funniest man in the world.” When he appeared as a guest in the panel game Looks Familiar he said, “I am the only person never to recognise Shirley Temple.”

Denis Gifford

* Denis Gifford died 20 May 2000

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.