Brittish Actors

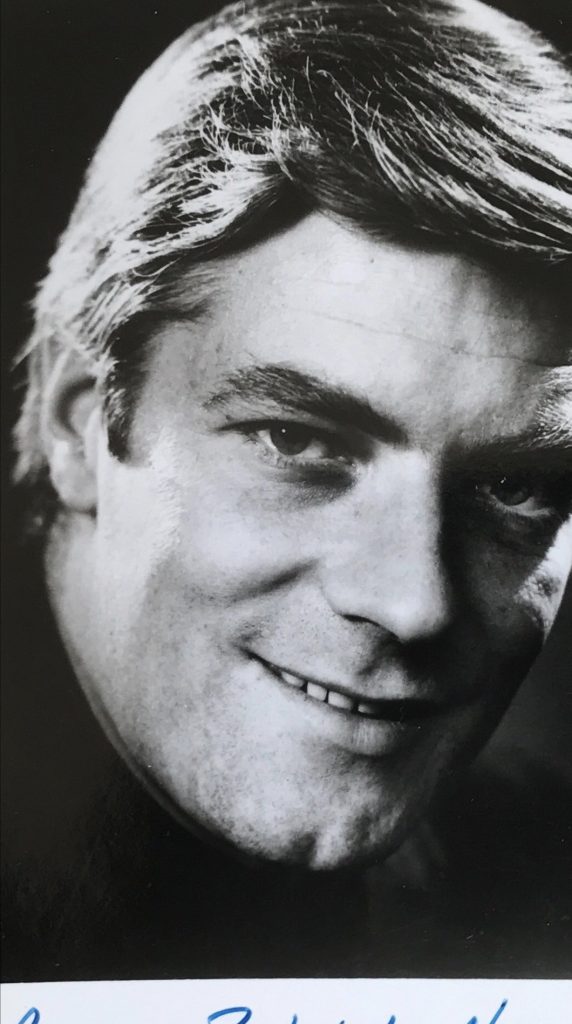

Dennis Lill was born in 1942 in Hamilton, New Zealand. Most of his career has been based in the U.K. He made his television debut in “Crossroads” in 1964. He had a major role in the mini-series “Fall of Eagles” in 1974. Other credits include series such as “The Regiment” and “Warship and movies such as “The Eagle Has Landed” in 1976.

Sean Arnold is best known for his role as ‘Crozier’ the Chief Inspector in “Bergerac” which ran from 1981 until 1990. He was bron in Gloucestershire in 1941. Other credits include “North Sea Hijack” in 1979, “Hunters of the Deep” and “Fuel”. Sean Arnold died in 2020 at the age of 79.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Elizabeth Counsell was born in 1942 in Windsor. She is the daughter of actress Mary Kerridge. Among Ms Counsell’s credits are “The Mind Benders” in 1963, “From Russia With Love”, “The Intelligence Men”, “Claudia” and more recen tly “Song For Marion” with Terence Stamp and Vanessa Redgrave.

Toby Stephens was born in 1969 in London. He is the son of actors Robert Stephens and Maggie Smith. He made his acting debut in 1992 in the miniseries “The Camomile Lawn”. He played the villian in the James Bond in “Die Another Day” in 2002. He also starred as ‘Rochester’ in “Jane Eyre” with Ruth Wilson.

TCM overview:

It was perhaps only natural that this second son of Sir Robert Stephens and Dame Maggie Smith should follow in his parents’ stead and pursue a career as an actor. Handsome, dark-haired Toby Stephens began to land key roles in stage and screen productions almost immediately after his 1991 graduation from LAMDA. He first made an impression with British TV audiences co-starring with Jennifer Ehle in “The Chamomile Lawn” in 1992, the same year he debuted on the big screen in “Orlando”.

Stephens went on to a distinguished stage career, joining the Royal Shakespeare Company and becoming the youngest actor with the troupe to undertake the lead in the Bard’s “Coriolanus” (1994). Daring to step into the shadow of Marlon Brando, he tackled the role of Stanley Kowalski opposite Jessica Lange in the 1996 Peter Hall-staged London production of “A Streetcar Named Desire”. His rising status as a leading man was cemented with his turn as Orsino in “Twelfth Night” (1996), Trevor Nunn’s feature adaptation of Shakespeare’s comedy, and as Gilbert Markham, the Yorkshire farmer who falls for a married woman, in the small screen version of Anne Bronte’s novel “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” (also 1996). Although his next couple of films didn’t fare too well at the box office, Stephens earned mostly good notices for his work, whether playing an early 20th-century photographer in “Photographing Fairies” (1997) or 19th-century men in “Cousin Bette” (1998) or “Onegin” (1999). After making his Broadway debut playing twins in the farcical “Ring Around the Moon” in 1999, the actor was tapped to portray the young incarnation of director-star Clint Eastwood’s astronaut in “Space Cowboys” (2000). That same year, he tried to embody F. Scott Fitzgerald’s elusive titular character in the A&E version of “The Great Gatsby”, but while he cut the proper dashing figure, something was missing in his interpretation of the role. He fared better in his homeland playing a supporting role in the critically-acclaimed BBC2 presentation “Perfect Strangers” (2001) and a return to the stage alongside Dame Judi Dench in “The Royal Family”. Director Neil LaBute tapped Stephens to play a self-serving academic in “Possession” (2002) before the actor landed a part that reach his wide audience yet– the villainous Gustav Graves in “Die Another Day” (2002), the 20th James Bond film. Stephens held his own against Pierce Brosnan as 007, proving one of the more charismatic of the recent Bond bad guys and demonstrating a flair for physical combat in the action-packed fencing sequence with Brosnan.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Michael Thoma was in the stage production of “The Caine Mutiny Court Martial” in London’s West End in 1983 with Charlton Heston and Ben Cross.

Imogen Stubbs was born in 1961 in Northumberland. She is a graduate of RADA. Her film debut was in 1982 in “Privileged”. Other movies include “Jack & Sarah”, and “Dead Cool”. On television, she starred in her own series “Anna Lee”.

TCM overview:

A classically-trained, blonde beauty, Stubbs was educated at Oxford (where her classmates included Hugh Grant and director Michael Hoffman) and at RADA. Primarily known in England for her stage performances at the Ipswitch Repertory Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Among her more notable roles include the leads in the musicals “The Boyfriend” and “Cabaret” and such classical parts as Helena in “The Rover” the Queen to Jeremy Irons’ “Richard II” and the title role in George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan”. Stubbs won critical marks for her turn as Stella to Jessica Lange’s Blanche in Sir Peter Hall’s London production of “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1996-97).

Stubbs made an impressive debut as the reactive title character in the British-French co-production “Nanou” (1987), which briefly featured Daniel Day-Lewis as the heroine’s friend. Subsequently she offered a poignant performance in Piers Haggard’s “A Summer Story” (1988), a period drama which saw her cast as a young woman whose heart is broken by a caddish barrister (James Wilby) and won praise as a seductive Norse princess in Terry Jones’ “Erik the Viking” (1989). She seemed slightly miscast as a Senator’s daughter in her American feature debut, “True Colors” (1991) but bounced back in two 1995 films. She was briefly seen as Richard E Grant’s wife who dies in childbirth in “Jack and Sarah” and was Emma Thompson’s rival for Hugh Grant’s affection in Ang Lee’s “Sense and Sensibility”. Stubbs co-starred as Viola in “Twelfth Night” (1996), directed by her husband Trevor Nunn.

Television has perhaps provided Stubbs with her widest audience. After co-starring in the British miniseries “The Rainbow” (shown in the US in 1989 on A&E), she tackled the lead in a series of TV-movies centering on a former policewoman now working as a private detective. As “Anna Lee”, Stubbs garnered critical praise and positive comparisons with Helen Mirren’s “Prime Suspect” character, Jane Tennison. To date, six installments have been aired in the US on A&E.

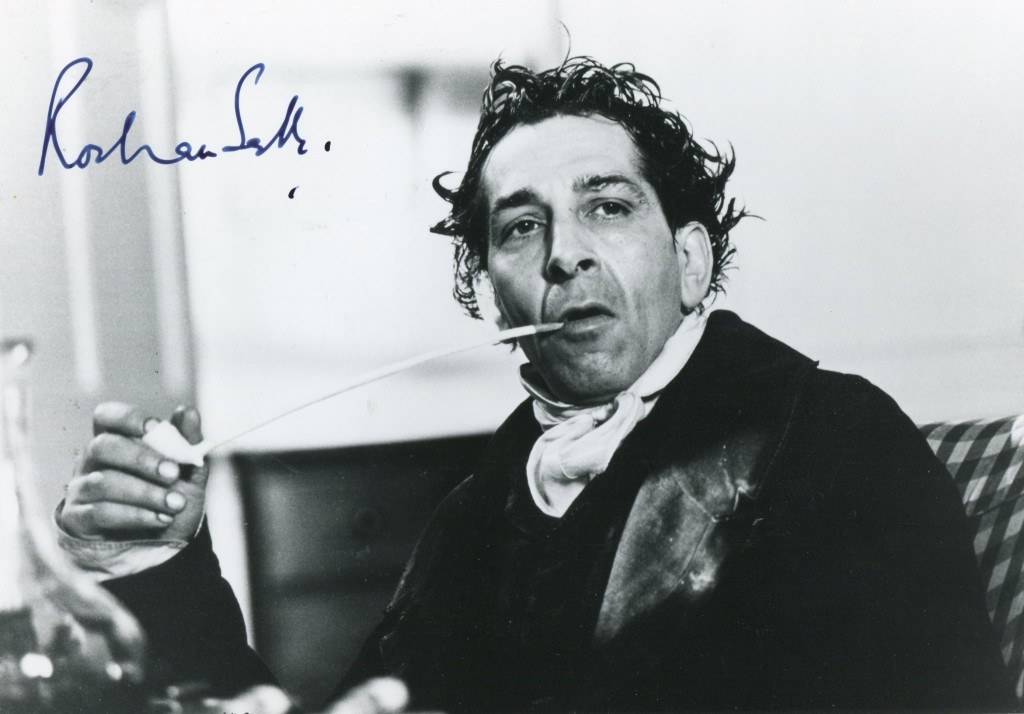

Roshan Seth was born in India in 1942. He is known for his critically acclaimed performances in the films “Gandhi“, “Mississippi Masala“, “My Beautiful Laundrette“, “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom“,,and “Street Fighter: The Movie“.

TCM overview:

An Indian-born, British trained character actor, Seth began his career after graduating from LAMDA in the late 1960s. He worked as an actor and director in British repertory before landing a role in Peter Brook’s version of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” which toured the USA in 1972. He made brief appearances on US TV shows and made his feature film debut in Richard Lester’s “Juggernaut” (1974). Because of his ethnicity, roles in classical productions were scarce and Seth decided to retire from acting and returned to India to pursue a career as a journalist and editor.

At the urging of Richard Attenborough, Seth returned to acting as Pandit Nehru in the biopic “Gandhi” (1982). Around the same time, playwright-director David Hare was casting the lead in his new play “A Map of the World” and he persuaded Seth to create the role of Victor Mehta, a sardonic and celebrated Indian author, first performed in Australia, then London and finally in NYC. Following the success of “Gandhi” and the stage role, Seth was cast as the duplicitous aide-de-camp of the young potentate in Steven Spielberg’s “Indian Jones and the Temple of Doom” and also appeared in David Lean’s “A Passage to India” (both 1984). Other roles followed including Mr. Pancks in Christine Edzard’s epic adaptation of “Little Dorrit” (1988), “Mountains on the Moon” and “1871” (both 1990). In 1991, Seth was a sympathetic Iranian in “Not Without My Daughter” and was the traditional-minded and racially intolerant father of a young girl in love with an African American in Mira Nair’s “Mississippi Masala”. In “Streetfighter” (1994), he was a biophysicist held captive by an evil dictator (Raul Julia).

In 1985, Seth began a collaboration with writer-director Hanif Kureishi. He played the left-leaning journalist father of a Pakistani youth (Gordon Warnecke) in Stephen Frears’ “My Beautiful Laundrette”, written by Kureishi. Six years later, he co-starred in Kureishi’s uneven feature directorial debut “London Kills Me” (1991) as the owner of a Sufi center. He reteamed with the screenwriter again for the four-part BBC TV miniseries “The Buddha of Suburbia” (1993) in which he played the father of the central character.

Norman Rodway was born in Dublin in 1929. He made his stage debut in 1953 at the Cork Opera House in “The Seventh Step”. His films include “This Other Eden” in 1959, “Four in the Morning”, “Chimes at Midnight” and “The Penthouse”. He died in 2001.

Dennis Barker’s “Guardian” obituary:

In the opinion of a new friend, the actor Norman Rodway, who has died aged 72 following a stroke, was “a bit of a rascal in the nicest possible way – the only little boy I know who is over 70”.

On stage, on television and on the big screen, he was often a professional Irishman, one who could play the gnarled Captain Jack Boyle in Sean O’Casey’s Juno And The Paycock, alongside Judi Dench, without anyone questioning his Irishness. Indeed, one of his first parts in London was the hero of James Joyce’s Stephen D, a pot-pourri of Joyce’s writings in which Rodway was well able to suggest the tensions existing in a Catholic Irishman half wanting to break free of his past.

In fact, he was born neither Catholic nor Irish, but was the son of a middle-class English father whose firm happened to send him to a post in Dublin just prior to his birth. His “Irishness” could nevertheless sometimes complicate things for his agent Scott Marshall when finding him non-Irish parts.

At Dublin high school, the youthful Rodway made his debut in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe, singing soprano. The following year, he appeared in a leading part in The Gondoliers, as a dressed-to-kill girl in black wig, crimson lipstick, heavy mascara and a 44-inch bust. This brought him his first encore at the end of the first act. By now, he knew that he wanted the stage to be his career.

Any impression of effeminacy that his soprano roles might have fostered at school was undercut by the fact that Rodway also starred as cricket captain, with top batting and bowling averages. His father had two private enthusiasms – cricket and opera – and had seen to it that his son was liberally exposed to both. At the age of nine, Rodway remembered practising his batting strokes against his father’s bowling in their back garden at Malahide, after which they went to his father’s study to listen to opera on the radio.

Cricket, and any branch of theatre, were to remain his enthusiasms, and his short, stocky frame, lantern jaw and piercing eyes were to make him especially adept at playing rascally or threatening parts, from Richard III, for the Royal Shakespeare Company, to Hitler, in the television psycho-drama The Empty Mirror, in which the dictator survived the war and had to face his crimes.

After winning a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin, where he took an honours degree in classics, Rodway spent a year teaching, a year lecturing, and even a very short time in the cost accountancy department of Guinness. While enduring these mundane ways of earning a living, he was also acting on a semi-professional basis in Dublin, where the line between professional and amateur tended to be more flexible than in Britain.

In 1953, he appeared in the first production by the newly-formed Globe Theatre Company, and was soon running the group with Jack McGowran and Godfrey Quigley, until they hit the financial skids eight years later. Fortunately, he had not severed all contact with London, where both his parents came from. He appeared in a Royal Court Theatre production of Sean O’Casey’s Cock-A-Doodle Dandy and, in 1963, settled in the capital permanently.

New things were happening in British theatre, and one of the people making them happen was John Neville, who ran the new Nottingham Playhouse and who invited Rodway to appear as Lopakin in his production of The Cherry Orchard. Three years later, Rodway joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, the beginning of a long association that saw his larger-than-life persona being used to best advantage.

After seeing the Laurence Olivier film version of Richard III 10 times, and watching Ian Holm on stage five times, Rodway took the leading role in Terry Hands’s 1970 production with such force that one critic commented that his performance, crowning a recent series of grotesque roles, was directly satanic – a spirit of evil driven on his course by self-loathing and, in particular, by loathing for his own body. “He is as ridiculous as he is villainous, and never more so than when he claps an outsize crown on that shaven bullet head.”

Rodway’s flare for arresting effects was perhaps better suited to the stage than to the cinema, but he appeared in many varying roles on the big screen, and even survived playing Hotspur in Chimes At Midnight (1966), in which Orson Welles both directed and played a Falstaff extracted from several Shakespeare plays. Rodway noticed that as shooting went on, Welles’s part got bigger and bigger, while his own got smaller and smaller. As always, Welles also periodically ran out of money, so that at one stage the film was impounded in a Spanish bank vault as a security for a debt.

The following year, as if paying tribute to his own stamina, Rodway appeared with Welles again, this time in I’ll Never Forget What’s ‘Is Name, with director Michael Winner on hand to prune the less acceptable parts of Welles’s ego. A romantic comedy was not Rodway’s main forte, but he also appeared in a supporting role to Suzy Kendall in Peter Collinson’s The Penthouse, another 60s cult film.

On television, his range was wider than his physical limitations. Apart from playing the dominant role of Hitler in The Empty Mirror, where his flare for outsize presence and gesture made the dictator like something out of a strobe-lit nightmare, he appeared in a number of televised Shakespeare plays, and was also a popular guest for one-off appearances in favourite series. These included Jeeves And Wooster, Miss Marple, Rumpole Of The Bailey, The Protectors and Inspector Morse. He made more than 300 broadcasts for BBC radio, including Brian Friel’s The Faith Healer, for which he won the 1980 Pye Radio Award for Best Actor.

Rodway was married four times, first to the actress Pauline Delany, then to the casting director Mary Sellway, and thirdly to the photographer Sarah Fitzgerald, by whom he had a daughter Bianca. She survives him, as does his fourth wife, Jane, whom he married in 1991.

Michael Pennington writes: Norman Rodway’s laughter came in two registers – a full-throated chuckle and a sort of incredulous trill. It was somehow to do with his conviction that everything was a form of comedy, including tragedy; nothing was more serious than the first, nothing more foolish than the second.

In the theatre, you sometimes catch up with your heroes. The Stephen D that arrived with a bang from Dublin in 1963 was an awesome buccaneer who would become my friend, and I learned that this red-blooded manner hid a spirit almost too delicate and fine – kind and anxious and always on your side. A first-class classical scholar, a pianist who could name every Köchel number in Mozart (but loved his Schubert even better), he was completely unpredictable in his judgment of a performance.

When he was ill and immobilised, his eyes locked on to you and followed you round the room, undeceived at the end, like the Lear he should have played. One of the very greatest radio performers, a Shakespearian to the heart, and a great spirit gone. I hope he’s laughing his laugh.

Norman Rodway, actor, born February 7 1929; died March 13 2001

For obituary on Norman Rodway, please click here.

Rodway, Norman John Frank (1929–2001), actor and theatre producer, was born 7 February 1929 in Dublin, son of Frank Rodway, manager of a shipping agency, and Lilian Rodway (née Moyles). The couple had recently moved to Dublin from London. They settled in Malahide, north of Dublin, where Norman attended St Andrew’s Church of Ireland national school before proceeding to the High School, Harcourt St., and to TCD on a scholarship. An excellent student, he graduated with first-class honours in classics in 1950. After lecturing briefly, he began working for Guinness’s brewery, while taking an accountancy degree. Stage-struck since school, he made his debut in the Cork Opera House in May 1953 as Mannion in ‘The seventh step’, and thereafter took on roles in Barry Cassin’s and Nora Lever’s 37 Theatre Club, where he met his first wife, the actress Pauline Delany, whom he married in 1954. That year he was made director of the recently established avant-garde Globe Theatre Company at the Gas Company Theatre, Dún Laoghaire, and the following year he turned professional actor.

Never an Abbey actor, he appeared frequently at the Gaiety, the Gate, and the Olympia and took leading roles in Christopher Isherwood’s ‘I am a camera’ (1956), and John Osborne’s ‘Epitaph for George Dillon’ (1959). As the Globe’s director, he accepted a play by the newcomer Hugh Leonard, ‘Madigan’s Lock’ (turned down by the Abbey), and played the lead when it opened at the Gate Theatre (where the Globe moved) in summer 1958. Leonard described Rodway as ‘modelled on Olivier, using the same vocal tricks, among them the sudden inflection that informed a moment of villainy with a subtext of sardonic humour’ (Sunday Independent, 18 March 2001). He played the Citizen in Leonard’s ‘A walk on the water’ for the 1959 Dublin Theatre Festival; it was the Globe’s last performance – the theatre shut down shortly afterwards – and Rodway went into partnership with Phyllis Ryan to found Gemini Productions, which produced William Gibson’s ‘Two for the seesaw’, Tom Murphy’s ‘Whistle in the dark’, and Leonard’s ‘The passion of Peter Ginty’, all featuring Rodway.

He scored his first major success as the title role in Leonard’s adaptation from James Joyce (qv), ‘Stephen D.’, which opened at the Gate in the 1962 Dublin Theatre Festival. When the play transferred to the West End, Peter O’Toole offered to play Stephen, but Leonard held out for Rodway, who received rave reviews. However, Leonard noted that T. P. McKenna, who came on in the second act as Cranly, always stole the play: ‘Rodway had every quality except the important one: star quality’ (Sunday Independent, 18 March 2001). For the 1964 Dublin Theatre Festival, Gemini Productions put on Leonard’s new play ‘The poker session’. It transferred to the West End and was not a success, but Rodway, who appeared as the assassin Billy Beavis, was much in demand; he moved to London and in 1966 was taken on by the Royal Shakespeare Company, with which he remained, on and off, till 1980. He rarely returned to Ireland but appeared in the 1971 Dublin theatre festival in Leonard’s irreverent farce ‘The Patrick Pearse Motel’.

In the 1966 RSC season he doubled the roles of Hotspur and Pistol in ‘Henry IV’, and played Feste in ‘Twelfth night’ and Spurio in Tourneur’s ‘The revenger’s tragedy’. Critics praised his intelligence and strong stage presence, helped by his big-boned, athletic physique and a head crowned with thick auburn hair. When he played Mercutio the following season, The Times wrote: ‘Norman Rodway unleashes his full range of grotesque comedy, orchestrating the fantastic tirades with rich pantomime and exhaustively milking the text for bawdy’ (14 September 1967). His first leading role for the RSC as Richard III in Terry Hands’s 1970 production was considered less successful. He generally excelled in supporting roles – particularly comic and Slavic parts. He played his first Chekhov in the Nottingham Playhouse’s ‘The cherry orchard’ in 1965 and was memorable in the RSC’s Gorky and Chekhov seasons (1974 and 1976). A natural choice for Irish roles on the London stage, he was notable as Sir George Thunder in ‘Wild oats’ (1977) by John O’Keeffe (qv), and outstanding as Captain Boyle to Judi Dench’s Juno in Trevor Nunn’s acclaimed production of Sean O’Casey‘s (qv) ‘Juno and the Paycock’ (Aldwych, 1980). The Times praised him for eschewing obvious comedy and cheap laughs.

Rodway had around forty film credits – generally small roles in low-budget films. His early films include This other Eden (1959), Nigel Patrick’s Johnny Nobody (1960), and Anthony Havelock-Allan’s The quare fellow (1962), all set and shot in Ireland. His appearance as Hotspur in Orson Welles’ Chimes at midnight(1966) persuaded Peter Hall to offer him that part in the RSC, and he starred opposite Judi Dench in Four in the morning (1966) which was given the award for best film at the Locarno Film Festival. Later in life, he playerd Hitler in the surreal film The empty mirror (1999).

His television career was more impressive; he had strong supporting roles in numerous series such as ‘Inspector Morse’, ‘Reilly: ace of spies’, ‘Rumpole of the Bailey’, ‘The professionals’, and ‘As time goes by’, and was a stalwart in Jonathan Miller’s productions of Shakespeare for the BBC. However, his greatest success off the stage was on radio, where his rich, expressive voice was much in demand. He appeared in 300 programmes and won a Pye award (the industry’s equivalent of an Oscar) for Brian Friel’s quartet of monologues, ‘Faith healer’, in 1980. His gift for comedy found expression in Alan Melville’s ‘Don’t come into the garden’ (1983) and as Apthorpe in Barry Campbell’s adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of honour (1974). After heart surgery in 1997 he gave up live theatre, and died, after a series of strokes, in Banbury, Oxfordshire, on 13 March 2001.

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.