Constance Cummings was an American actress whose fame stems from her career in Britain. She was born in 1910 in Seattle, Washington State in the U.S. She went to Hollywood in 1931 and made twenty films there until 1934. That year she moved to the U.K. after her marriage to the British playwright Benn Levy. Among her film credits are “Blythe Spirit” in 1945, “The Battle of the Sexes” in 1959 and “In the Cool of the Day” in 1963. She had an extensive stage career in the West End. She died in 2005 at the age of 95.

Eric Shorter’s obituary in “The Guardian”:

Constance Cummings, who has died aged 95, was a Broadway chorus girl who met the English playwright Benn Wolfe Levy in Hollywood before the second world war and became one of the most accomplished film and stage actors on either side of the Atlantic.

Whether in tragedy, farce, comedy or melodrama, Cummings, the daughter of a Seattle lawyer and a concert soprano, seldom failed to surprise. From being what a London critic, in 1934, called “a film star who can act”, she learned, under her husband’s direction, how to play (as James Agate put it) “anything from pitch-and-toss to manslaughter”. It was in one of Levy’s plays, Young Madame Conti (1936), that Agate decided she “immediately takes rank, even on the strength of one performance, as an contestably fine emotional actress”. In Goodbe Mr Chips, he thought her “the most beautiful thing of the evening”, reminding him “of the fragrance and pathos, sensitiveness and radiance of the great actresses of our youth”.

How did this upstart American blonde with the peaches-and-cream complexion, beautifully waved hair and feminine curves become an actor of such exceptional power? It is true that her finest achievements – The Shrike, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Long Day’s Journey into Night, and Wings – were all American plays, and that many of her West End successes were in her husband’s plays, or in plays he directed.

All the same, here was a talent, best known on the screen, which turned to the theatre with sustained success and in the highest reaches of that art. Not everything she did bowled everyone over, while her looks did sometimes get in the way. As Robert Donat’s Juliet (1939), for example, with the Old Vic company in wartime exile at Buxton and at Streatham Hill, she admitted: “I didn’t know how to read the verses. That was a sloppy thing. I should have had more sense.”

In the West End, however, it was the sparkling personality, wit and virtually invisible technique that made her art so attractive, especially in her husband’s sophisticated pieces – such as Clutterbuck (1946), Return to Tyassi (1950), The Rape of the Belt (1957) and Public and Confidential (1966), in which her line in mordant comedy as an MP’s secretary-mistress was needle-sharp.

But the depths of her emotional potential, tantalisingly glimpsed as the anxious wife of Michael Redgrave’s alcoholic actor in Clifford Odets’s Winter Journey (1952), remained veiled until Joseph Kramm’s The Shrike. Here, opposite Sam Wanamaker, Cummings disclosed an arresting side to her talent – “a spiked knuckle duster in a velvet glove,” as Kenneth Hurren put it.

Meanwhile, at the Oxford Playhouse Frank Hauser could offer a taste of the true classics in Lysistrata (1957), in which she proved alluringly militant. In 1962, she played a double bill of Sartre’s Huis Clos and Max Beerbohm’s A Social Success, followed by Aldous Huxley’s The Genius and the Goddess.

The Huxley play (which promptly moved into the West End) was right up her street: an adorable, ravishing, witty and self-possessed hostess. On the other hand, Sartre’s ugly lesbian, Inez, was not. At first, Cummings was “horrified”. Until, that was, rehearsals, when she began to enjoy it. “I found little seeds of her dreadfulness in myself, things I could build on. It was a marvellous liberation. I’d never opened myself before and taken such a plunge.”

Most playgoers had to wait, though, for her Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1964) to realise this branch of the talent. It cannot have been easy to follow Uta Hagen’s famous ferocity, but I shall never forget it because I never supposed it possible. What Cummings did amid all the sound and fury was to hint at an element of feminine refinement.

Here, then, was a neo-tragedienne. But as Gertrude to Nicol Williamson’s controversial Hamlet (1969), her art did not thrive, nor did it in 1971 when she joined Laurence Olivier’s National Theatre in Coriolanus, playing Volumnia to Anthony Hopkins in the title role.

The same year yielded Cummings’ finest hour, as Mary Tyrone, frail matriarch to an Irish-American family ruled by Laurence Olivier’s actor-father in Michael Blakemore’s revival of Long Day’s Journey into Night. Here Cummings found an authority, pathos and emotional integrity which had the house holding its breath before and after her every entrance. The transformation from a gentle maternal presence to fully-fledged morphine addict was a triumph of artistic delicacy.

There were no comparable triumphs to come, though her Madame Ranevsky, to Michael Hordern’s Gaev in a revival at the National of The Cherry Orchard (1973) was well received, and as a mentally ill woman trying to recover from a stroke in Arthur Kopit’s Wings, at the Cottesloe in 1978, she was judged superb, though some thought the tug at the emotions too obvious. The performance won a Tony award on Broadway.

If, by chance, there was nothing doing in London, Cummings would go to the regions, where most of the best acting parts were usually to be found – in Tennessee Williams (The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Any More) at Glasgow, Bernard Shaw (Mrs Warren’s Profession) at Bristol, Edward Albee (All Over) at Brighton, Somerset Maugham (The Circle) at Guildford or Friedrich Durrenmatt (The Visit) at Coventry. Her last West End performance was in Uncle Vanya in 1999.

Her husband, whom she married in 1933, died in 1973. After his death, she kept up their 600-acre dairy farm in the village of Cote, Oxfordshire. Levy had been a Labour MP in the postwar Atlee government, and Cummings supported causes such as Amnesty and Liberty, and did much work for the Actors’ Charitable Trust. She received in 1974 the CBE.

She is survived by her children Jonathan and Jemina.

Ronald Bergan writes: In 1930, the 20-year-old Cummings was brought to Hollywood by Sam Goldwyn to co-star with Ronald Colman in The Devil to Pay, but was replaced at the last minute by 17-year-old Loretta Young. However, her disappointment was allayed when Columbia Pictures snapped her up, gave her a contract and cast her as prison warden Walter Huston’s naive daughter in Howard Hawks’s The Criminal Code the following year.

Columbia was so impressed by this debut that they starred Cummings in 10 films in two years, even though most were modest productions. The exception was Frank Capra’s New Deal fantasy, American Madness (1932), in which, with much charm and passion, she played a bank employee supporting her boss’s determination to lend money on the collateral of his clients’ good characters.

After leaving Columbia, Cummings went freelance, enabling her to appear in one of her most delightful films, the Harold Lloyd comedy, Movie Crazy (1932). In Night after Night (also 1932), as a classy lady with whom George Raft is in love, she managed to shine even after the entry of Mae West, in her screen debut. Her final Hollywood film before leaving for England was the comedy-whodunit Remember Last Night? (1935), with Robert Young.

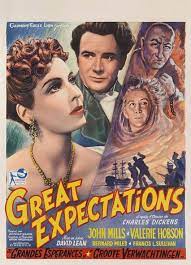

In England, Americans Robert Montgomery and Cummings were unaccountably cast in Busman’s Honeymoon (1940), as Lord Peter Wimsey and his mystery writer wife, Harriet Vane. She did get to play a brave American ally in The Foreman Went to France (1942), and was convincing as the upper middle-class wife of Rex Harrison in David Lean’s Blithe Spirit (1945). The problem was that Cummings was far more attractive than Kay Hammond in the role of Harrison’s first wife.

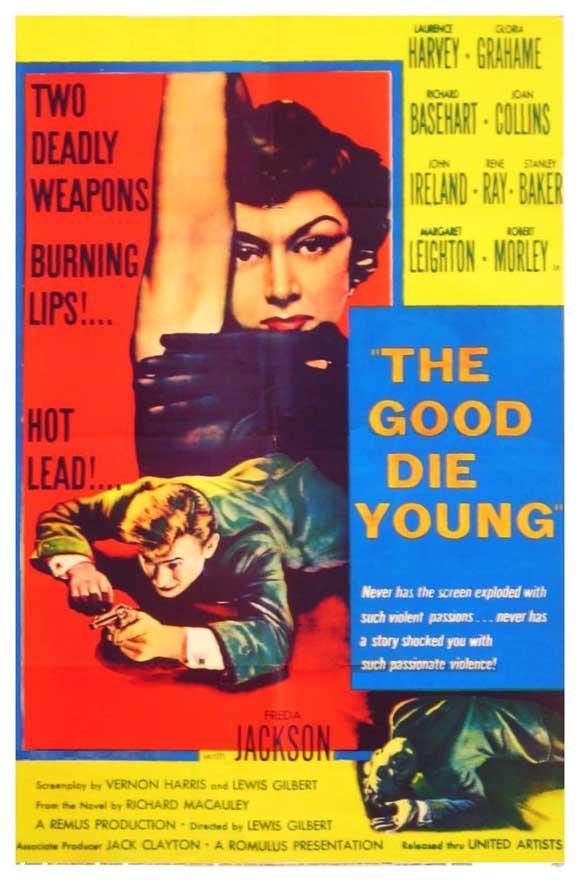

Among Cummings’s few films in the 1950s was The Intimate Stranger (1956), directed by blacklisted Joseph Losey (under the pseudonym Joseph Walton). In it, she played a film star causing problems for director Richard Basehart. Her last really good film role was in Charles Crichton’s The Battle of the Sexes (1959), as Mrs Barrow, the American efficiency expert sent to modernise an Edinburgh textile firm. Seeing his way of life threatened, the mild accountant (Peter Sellers) tries to murder her. Cummings was so unsympathetic that audiences willed him on. Unfortunately, the cinema’s loss was theatre’s gain, and she was seen only rarely in films after that.

· Constance Cummings Levy, actor, born May 15 1910; died November 23 2005

The above Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.