Derek Jacobi was born in 1938 in London. Came to international prominence in 1976 for his powerful performance on television in the series “I, Claudius”. Although primarily a major actor on stage, he has starred in such films as “The Day of the Jackel” in 1973, “The Odessa File”, “Little Dorrit” and “Gosford Park”. Currently starring in the hit BBC series “Last Train To Halifax”.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

Preeminent British classical actor of the first post-Olivier generation, Derek Jacobi was knighted in 1994 for his services to the theatre, and, in fact, is only the second to enjoy the honor of holding TWO knighthoods, Danish and English (Olivier was the other). Modest and unassuming in nature, Jacobi’s firm place in theatre history centers around his fearless display of his characters’ more unappealingly aspects, their great flaws, eccentricities and, more often than not, their primal torment.

Jacobi was born in Leytonstone, London, England, the only child of Alfred George Jacobi, a department store manager, and Daisy Gertrude (Masters) Jacobi, a secretary. His paternal great-grandfather was German (from Hoxter, Germany). His interest in drama began while quite young. He made his debut at age six in the local library drama group production of “The Prince and the Swineherd” in which he appeared as both the title characters. In his teens he attended Leyton County High School and eventually joined the school’s drama club (“The Players of Leyton”).

Derek portrayed Hamlet at the English National Youth Theatre prior to receiving his high school diploma, and earned a scholarship to the University of Cambridge, where he initially studied history before focusing completely on the stage. A standout role as Edward II at Cambridge led to an invite by the Birmingham Repertory in 1960 following college graduation. He made an immediate impression wherein his Henry VIII (both in 1960) just happened to catch the interest of Olivier himself, who took him the talented actor under his wing. Derek became one of the eight founding members of Olivier’s National Theatre Company and gradually rose in stature with performances in “The Royal Hunt of the Sun,” “Othello” (as Cassio) and in “Hay Fever”, among others. He also made appearances at the Chichester Festival and the Old Vic.

It was Olivier who provided Derek his film debut, recreating his stage role of Cassio in Olivier’s acclaimed cinematic version of Othello (1965). Olivier subsequently cast Derek in his own filmed presentation of Chekhov’s Three Sisters (1970). On TV Derek was in celebrated company playing Don John in Much Ado About Nothing (1967) alongsideMaggie Smith and then-husband Robert Stephens; Derek had played the role earlier at the Chichester Festival in 1965. After eight eventful years at the National Theatre, which included such sterling roles as Touchstone in “As You Like It”, Jacobi left the company in 1971 in order to attract other mediums. He continued his dominance on stage as Ivanov, Richard III, Pericles and Orestes (in “Electra”), but his huge breakthrough would occur on TV. Coming into his own with quality support work in Man of Straw (1972), The Strauss Family (1972) and especially the series The Pallisers (1974) in which he played the ineffectual Lord Fawn, Derek’s magnificence was presented front and center in the epic BBC series I, Claudius (1976). His stammering, weak-minded Emperor Claudius was considered a work of genius and won, among other honors, the BAFTA award.

Although he was accomplished in The Day of the Jackal (1973) and The Odessa File(1974), films would place a distant third throughout his career. Stage and TV, however, would continue to illustrate his classical icon status. Derek took his Hamlet on a successful world tour throughout England, Egypt, Sweden, Australia, Japan and China; in some of the afore-mentioned countries he was the first actor to perform the role in English. TV audiences relished his performances as Richard II (1978) and, of courseHamlet, Prince of Denmark (1980).

After making his Broadway bow in “The Suicide” in 1980, Derek suffered from an alarming two-year spell of stage fright. He returned, however, and toured as part of the Royal Shakespeare Company (1982-1985) with award-winning results. During this period he collected Broadway’s Tony Award for his Benedick in “Much Ado about Nothing”; earned the coveted Olivier, Drama League and Helen Hayes awards for his Cyrano de Bergerac; and earned equal acclaim for his Prospero in “The Tempest” and Peer Gynt. In 1986, he finally made his West End debut in “Breaking the Code” for which he won another Helen Hayes trophy; the play was then brought to Broadway.

For the rest of the 80s and 90s, he laid stage claim to such historical figures as Lord Byron, Edmund Kean and Thomas Becket. On TV he found resounding success (and an Emmy nomination) as Adolf Hitler in Inside the Third Reich (1982), and finally took home the coveted Emmy opposite Anthony Hopkins in the WWII drama The Tenth Man (1988). He won a second Emmy in an unlikely fashion by spoofing his classical prowess on an episode of “Frasier” (his first guest performance on American TV), in which he played the unsubtle and resoundingly bad Shakespearean actor Jackson Hedley.

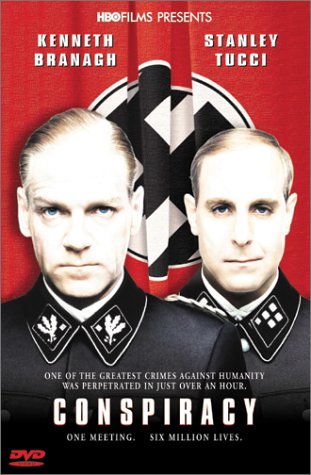

Kenneth Branagh was greatly influenced by mentor Jacobi and their own association would include Branagh’s films Henry V (1989), Dead Again (1991), and Hamlet (1996), the latter playing Claudius to Branagh’s Great Dane. Derek also directed Branagh in the actor’s Renaissance Theatre Company’s production of “Hamlet”. In the 1990s Derek returned to the Chichester Festival, this time as artistic director, and made a fine showing in the title role of Uncle Vanya (1996).

More heralded work of late includes a profound portrayal of the anguished titular painter in Love Is the Devil: Study for a Portrait of Francis Bacon (1998), and superb theatre performances as Friedrich Schiller‘s “Don Carlos” and in “A Voyage Round My Father” (2006).

He and his life-time companion of 27 years, actor Richard Clifford, filed as domestic partners in England in 2006. Clifford, a fine classical actor in his own right, has shared movie time with Jacobi in Little Dorrit (1988), Henry V (1989), and the TV version ofCyrano de Bergerac (1985).

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net