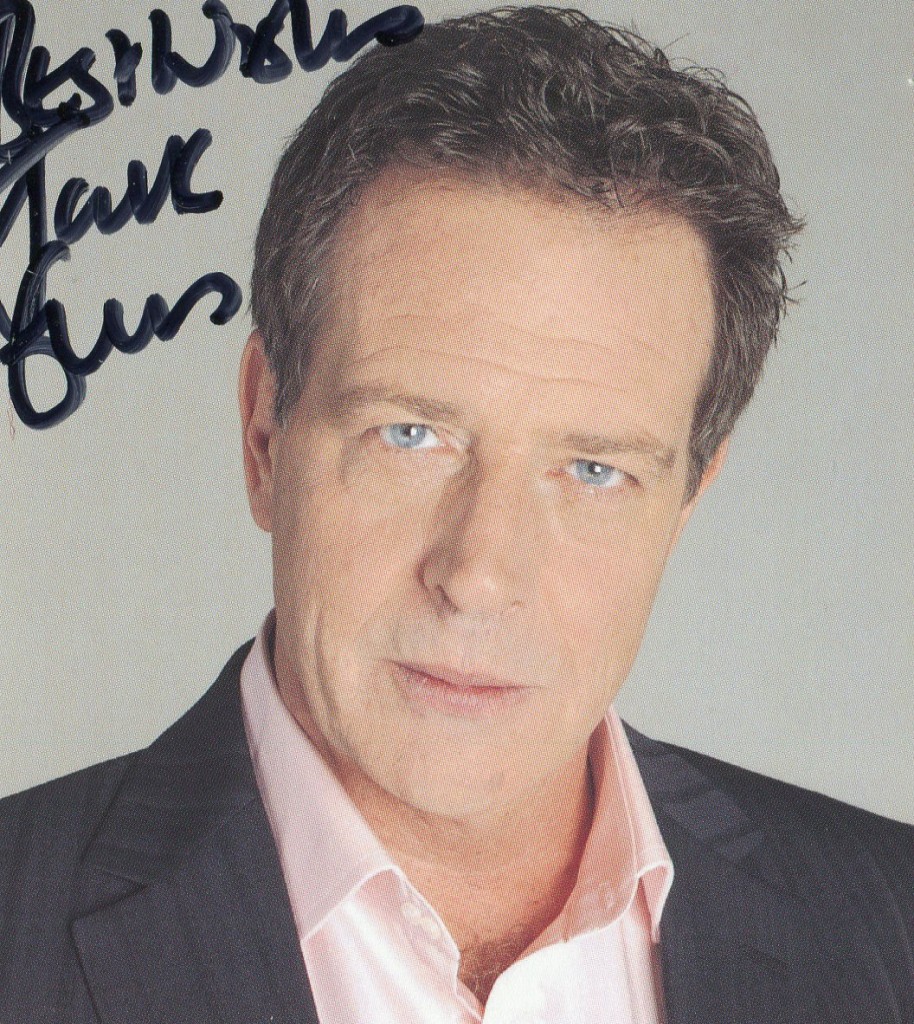

James Faulkner. TCM Overview.

James Faulkner was born in 1948 in Hampstead, London. In 1972 he made his flm debut in “The Great Waltz”. He starred in “Conduct Unbecoming” with Michael York and Susannah York. He has had a very extensive career on television and the stage.

TCM Overview:

In a career that spanned several decades, English actor James Faulkner appeared in numerous television series and films, primarily as a supporting actor in small character roles. With a wide degree of versatility, the classically-trained thespian tackled everything from Shakespeare to Japanese anime, and boasted a resume that included roles in Hollywood blockbusters like “X-Men: First Class” (2011).

James Sebastian Faulkner (who on occasion was credited by his full name on screen) was born on July 18, 1948 in Hampstead, London, England. Before he went into acting, Faulkner attended Caldicott Preparatory School, followed by Farnham Royal. After he finished his years at Wrekin College, Faulkner enrolled himself at London’s Royal Central School of Speech and Drama (now part of the University of London). For three years between 1967 and 1970, Faulkner honed his acting skills in preparation for tackling the English theater. Near the tail end of his academic career as an actor, Faulkner was cast in a regional adaptation of William Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing.” For a couple of years, Faulkner continued take on small roles on the British theater circuit before he was cast in the key role of Appollodaurus in an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s “Caesar & Cleopatra” in 1971.

The very next year, Faulkner began acting in feature films. His first film was a musical biopic of Austrian classical composer Johann Strauss, “The Great Waltz” (1972), in which he played Strauss’s son, Josef. His first role on the small screen came when he appeared in an episode of the gritty Glasgow-based TV police drama “The View from Daniel Pike” (BBC 1971-73). Faulkner continued to land supporting roles in both film and television, interspersed with theater work that explored Shakespeare’s tragedies and histories. Having spent his cinema career in front of the camera, Faulkner was credited as a co-producer of the historical war film “Zulu Dawn” (1979), the prequel to the hugely successful “Zulu” (1964). Depicting the events of the Battle of Isandlwana in southern Africa during the 19th century, the drama starred Peter O’Toole and Burt Lancaster. Along with his production duties, Faulkner also played the supporting role of British military officer Lt. Melvill.

In the 1980s and ’90s, Faulkner’s prolific career expanded to an international audience. He played Baron John Mullens in an American-made television drama set in the Middle Ages, “Covington Cross” (ABC 1992). Faulkner also lent his voice to bring animated characters to life, such as Franc in the Japanese anime “Najica: Blitz Tactics” (2001). Faulkner’s vocal talents continued to land him jobs for other popular anime shows. “Noir” (2001), “Full Metal Panic!” (2002) and “Gantz” (2004) are just few of the anime shows that featured Faulkner’s distinct voice in between his supporting roles in a diverse portfolio of genres. He appeared alongside fellow British actors Hugh Grant and Colin Firth in the hit comedy “Bridget Jones’s Diary” (2001). Faulkner was seen in the kid-friendly adventure “Agent Cody Banks 2: Destination London” (2004), the drama “The Good Shepherd” (2006), and the action-packed “Hitman” (2007) based on the eponymous video game. Faulkner’s versatility garnered the attention of screenwriter David S. Goyer. In “Da Vinci’s Demons” (Starz 2013-), Goyer cast Faulkner as Pope Sixtus IV in his fictional depiction of the Renaissance man’s life.

TCM overview can also be accessed online here.