TCM overview:

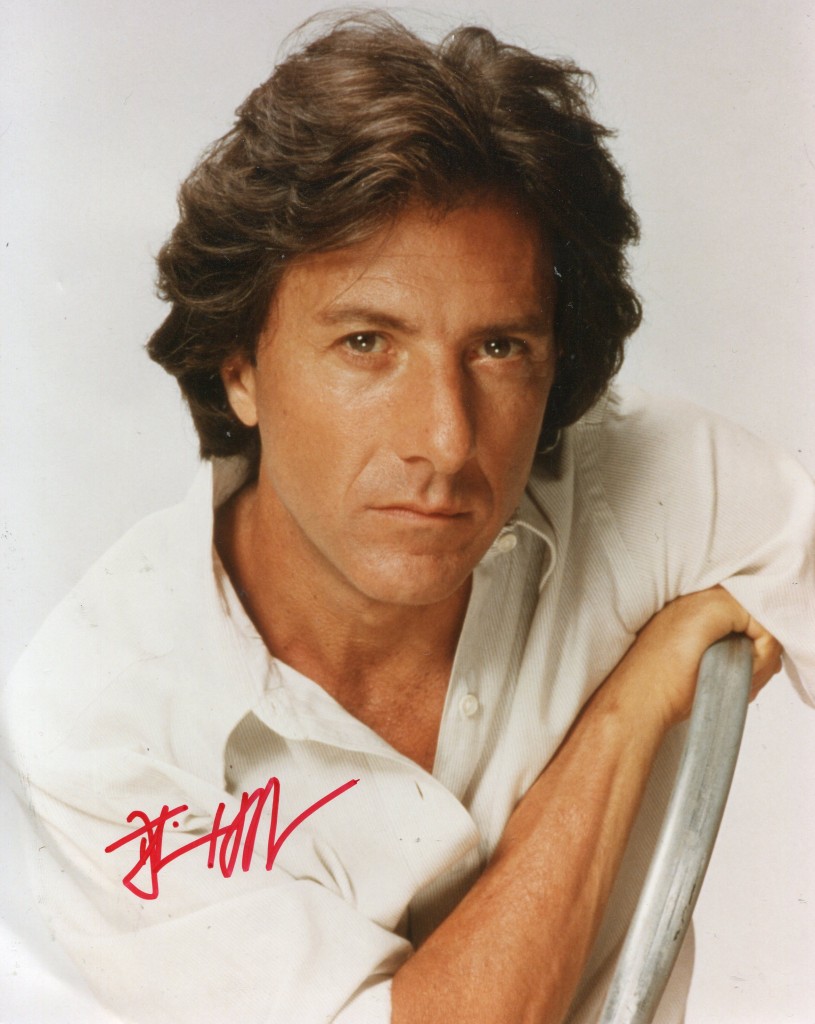

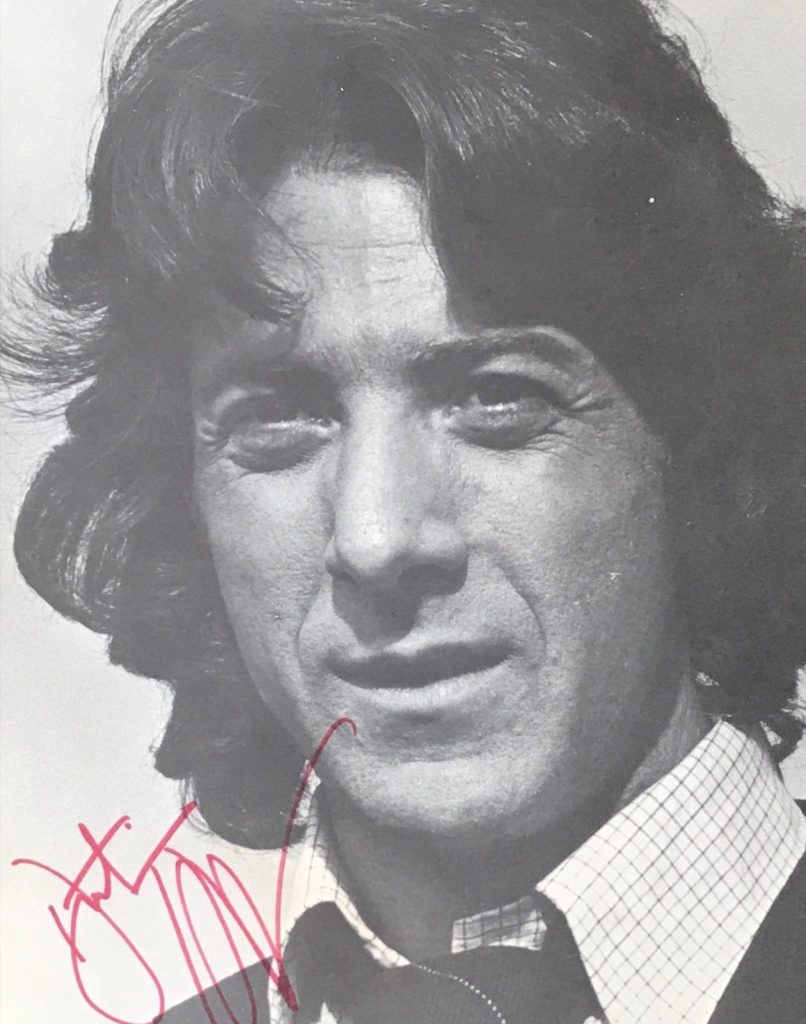

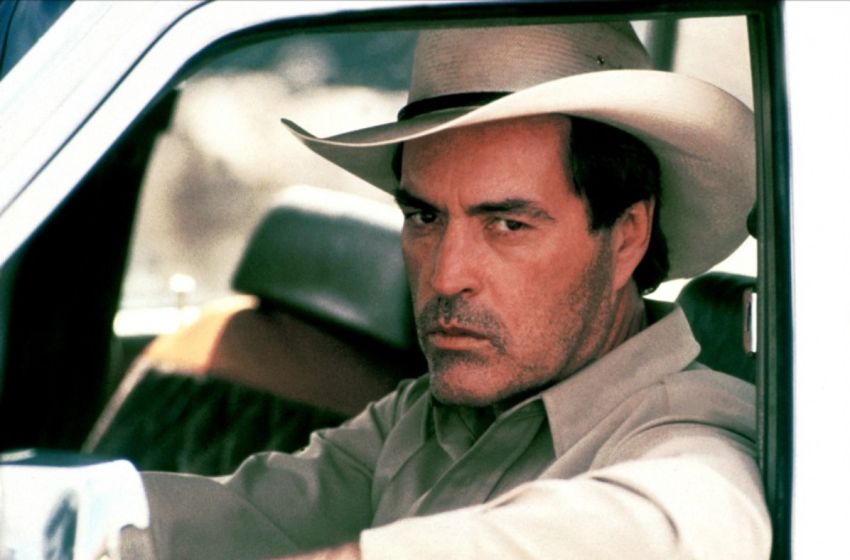

Prolific British film actor Michael Caine rose to fame as an icon of London’s ‘swinging ’60s,’ but four decades later, having contributed to some of cinematic history’s highest and lowest moments, he was recognized as an international film legend. Caine initially seemed an unlikely movie star, with his glasses and working class cockney accent, but with films like “The Ipcress File” (1965) and “Alfie” (1966), he came to personify the cultural upheaval of 1960s Britain, when the smashing of class barriers finally meant that regular blokes had a shot at the spotlight. With his foundation in repertory theater, Caine had already played hundreds of characters by the time he hit it big, and that background made him one of the most versatile leading actors on film. He deftly transitioned from gritty mobster (“Get Carter”), to scheming soldier (“The Man Who Would Be King”), warm-hearted doctor (“The Cider House Rules”), charming con man (“Dirty Rotten Scoundrels”), erudite professor (“Educating Rita”) to transvestite psychologist murderer (“Dressed to Kill”). Caine convincingly inhabited some of the best-known characters in literature and world history – not through self-analysis and method acting, but by holding up a mirror to the audience, presenting them with truths about themselves. His realistic acting style and ability to connect with an audience earned the actor a reputation for being approachable and down-to-earth, despite his ultra-luxury lifestyle and bona fide star status. For Caine, this was no act, as he had risen from the poorest of the poor with all odds seemingly stacked against him.

Michael Caine was born Maurice Joseph Micklewhite Jr. in the charity wing of St. Olaves hospital in the Rotherhithe area of South London on March 14, 1933. The child of a fish market worker (with an unlucky gambling habit) and a cleaning woman, Caine was born with rickets from prenatal malnutrition and wore leg braces as a child. He was also diagnosed with blepharitis – an inflammation of the eyelids responsible for his heavy-lidded look, and a mild facial tic that was then known as St. Vitus dance. Caine’s younger brother Stanley was born two years later, and the family lived in a two-room flat with no electricity or running water. Generations of earlier Micklewhites may have been satisfied working at the fish market, but Caine – a voracious reader and avid moviegoer – knew that there was a better life out there and he was going to live it. However, there was little encouragement or opportunity for young working class toughs like Caine to explore drama. West End theaters were out of reach, drama lessons were unheard of, and the family did not have a TV, so for Caine, the movie theater became his second home. He idolized Humphrey Bogart, as much for the powerful onscreen characters he created as for the luxurious movie star lifestyle he lived, but Caine had no idea how one even began the journey from his South London flat to a Hollywood mansion. And the code of his class dictated that he was born a cockney and that was all he would ever be. But Caine’s intelligence and interest in the arts did make him different from the street gangs who did not quite accept him. He was finally given the chance to explore his interests at the age of 14, when he joined a local youth program designed to keep kids off the street. Their drama department gave Caine his first exposure to the stage, and he appeared in all their stage productions, as well as found a mentor in a film history teacher and short filmmaker who worked with the group, giving Caine an early education in filmmaking.

Caine left school at 16 and landed an entry-level production job at an industrial film company. At 18, he was called upon to do military service, and for the next two years, served overseas and even saw frontline combat in Korea. He made his glorious re-entry into civilian life working at a butter factory before landing a job as an assistant stage manager and eventually an actor at a repertory theater in West Sussex. However, a bout of post-war malaria forced him offstage for a time. After his recovery, he joined another repertory theater in the seaside town of Lowestoft. As with his earlier position, Caine barely made enough money to cover his living expenses, but the experience proved to be invaluable, with the actor often having to learn a new role every week.

While in Lowestoft, Caine met and fell in love with fellow troupe member Patricia Haines. The couple married and moved to London to try their acting luck, but Haines fared better. With his roles few and far between, Caine was forced to work as a plumber’s assistant and a baker. The financial pressure proved to be too much for the young couple, especially after the birth of their daughter, leaving both to eventually move back home with their parents and to divorce. Caine’s father died shortly thereafter and with the walls closing in on him, he escaped to Paris for a month, wandering the streets and sleeping in subway stations and brothels. He eventually dragged himself home to find a telegram from his agent, offering him a bit part in the military drama “Hell in Korea” (1956). This led to small, mostly uncredited appearances in more films and TV, alternating with civilian jobs and frequent moving from one cheap roommate situation to another. His misery had plenty of company, as he had made scores of friends who were struggling artists and actors, all hoping against hope that they would someday be household names – Harold Pinter, Terence Stamp, David Hockey, even his barber, Vidal Sassoon.

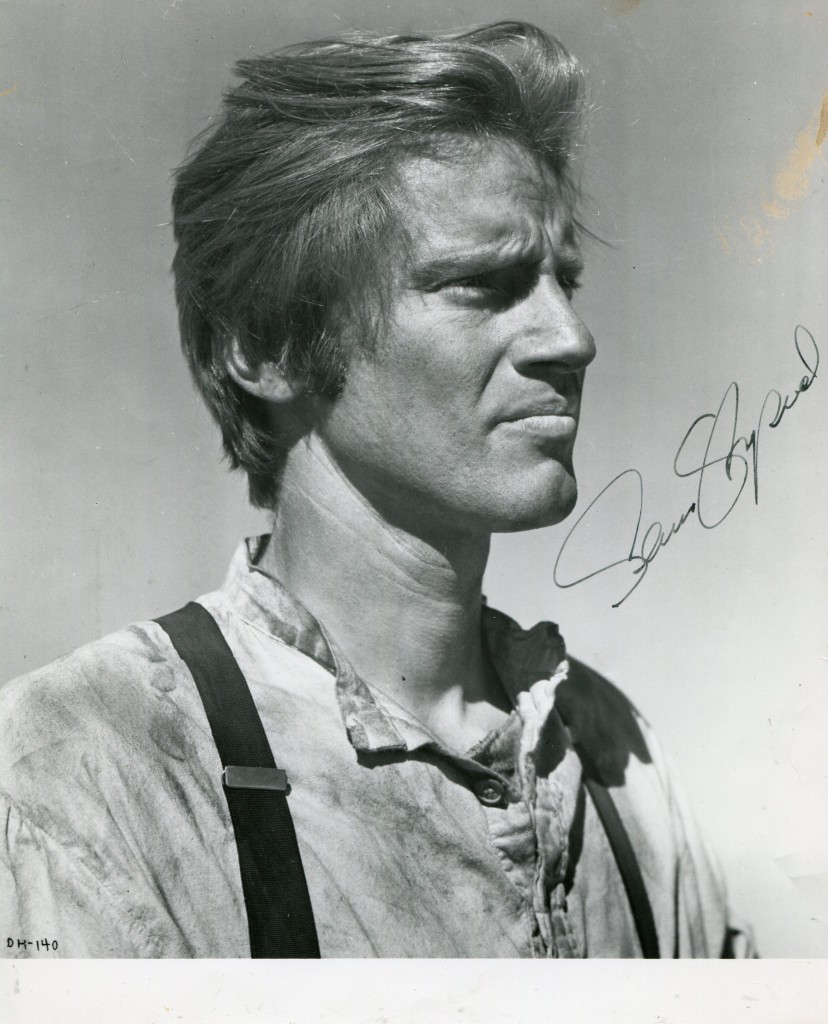

Caine, who had by now officially changed his stage name to Caine in order to appear in an actor’s equity production, carried on with play after play, eventually making it to the London’s famed West End in 1963. He understood that stage was his training ground, but Caine’s sights were still firmly set on becoming a film actor of the most glamorous sort. Not long afterwards, he went on an audition for a role as a cockney soldier in a war film, only to have the American director take one look at his lean frame and long blond locks and instead cast him in a leading role as an upper crust army officer. “Zulu” (1964) was truly Caine’s breakthrough, earning him more money than he had ever seen, as well as an offer to star in the espionage thriller “The Ipcress File” (1965) and a seven-year film contract. In “The Ipcress File,” Caine played working-class spy Harry Palmer – the antithesis of James Bond’s ridiculous glamour – who drank pints of beer rather than shaken martinis, and whose mode of transport was a public bus, not a snappy sports car. Caine gave an exceptional performance; his matter-of-fact delivery perfectly suited for the part. With his salary of 10,000 pounds a week, he moved his mother to a nicer flat, got himself a new place, and outfitted it with the best of everything.

“Ipcress” won Caine sizable fame, but “Alfie” (1966) succeeded in making the long-struggling, 33-year-old actor a household name. A swinging cockney cad with a great tailor and insatiable appetite for the ladies, Caine’s Alfie – along with the success of the Beatles – signaled a major shift in the British cultural voice away from the elite aristocracy and towards anyone who wanted to join the youth-driven party. Caine earned an Oscar-nomination for “Alfie” and made his U.S. debut later that year opposite Shirley MacLaine, who invited him to appear in the enjoyable comic caper “Gambit.” The full-time movie star reprised Harry Palmer with “Funeral in Berlin” (1966) and “Billion Dollar Brain” (1967), before churning out two American films for 20th Century Fox – “Deadfall” (1968) and “The Magus” (1968) – and starring in one of the most memorable films of his career, the action comedy classic, “The Italian Job” (1969).

Caine had established himself with wry, street smart characters who were ultimately likeable even when they were up to no good, but there was nothing he could not or would not tackle. Evolving with the climate of the times, Caine reflected the grittier, more violent atmosphere of the city streets with 1971’s landmark action film “Get Carter,” playing a hit man searching for the man who killed his own brother. In 1972, he held his own opposite acting giant Laurence Olivier in the psychological tete a tete, “Sleuth,” earning his second Best Actor Oscar nomination. In 1975, Caine was thrilled to receive an offer from director John Huston to take the leading role initially intended for his hero Humphrey Bogart in the epic adventure “The Man Who Would Be King.” He next revisited his flair for comedy in the classic Neil Simon ensemble romp “California Suite” (1978), playing a British tourist in Beverly Hills. Forever worried that his fortune might dry up and his fame disappear, Caine tried to stay as busy as possible, which explained why he finished out the decade with horrific missteps, “The Swarm” (1978) and “Beyond the Poseidon Adventure” (1979).

Caine had spent considerable time stateside during his career. With penal taxes threatening to bankrupt him, he and his second wife Shakira (also an actress and co-star of “The Man who Would Be King”) and their daughter moved to the famed Hollywood Hills, with Caine officially realizing his childhood dreams of the movie star life. He was welcomed to America with an offer from controversial director Brian DePalma to play a transvestite psychiatrist in his stylized thriller “Dressed To Kill” (1980) and one from Sidney Lumet to play opposite Christopher Reeve in the thriller “Deathtrap” (1982), which generated controversy for an onscreen kiss between the co-stars. With Caine’s next film, “Educating Rita” (1983), any recent trespasses were soon forgotten. Caine took home Golden Globe and BAFTA awards as well as another Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Dr. Frank Bryant, a college professor and failed poet whose alcoholic self-loathing turns a corner when he begins tutoring a hairdresser (Julie Walters) looking to improve her lot in life. Caine played the complexities of Bryant’s despairing soul with a stirring subtlety that reminded audiences why he had been a leading man for 20 years.

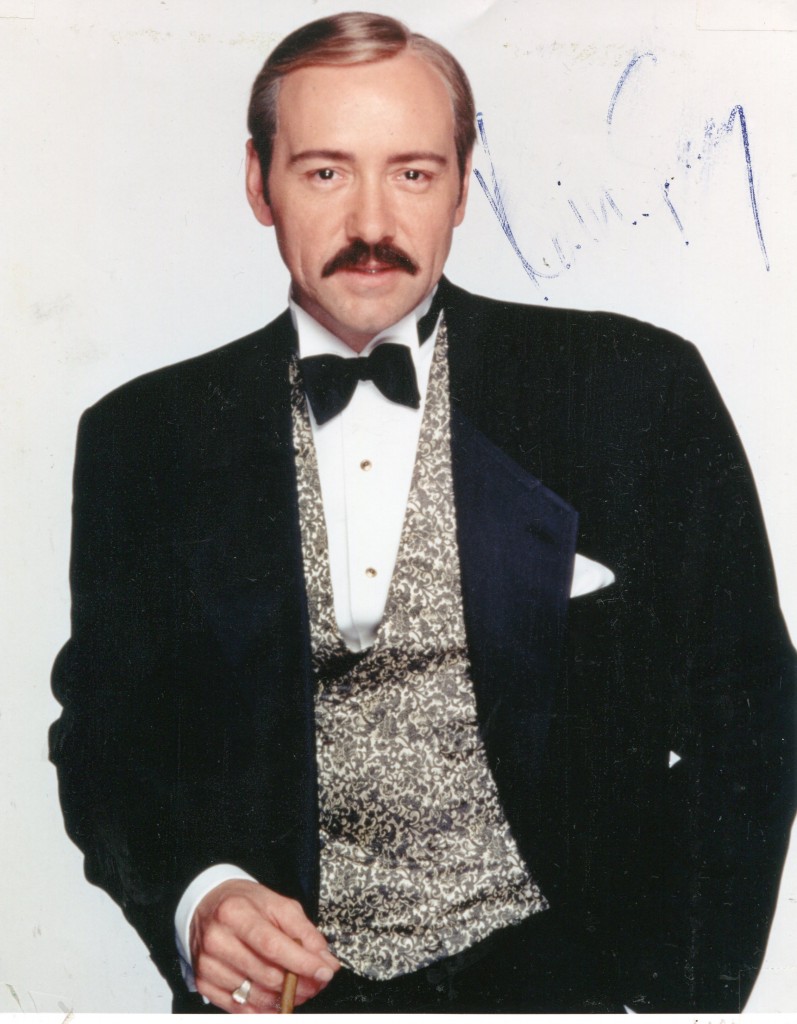

Caine finally picked up an Oscar in the Best Supporting Actor category for “Hannah and Her Sisters” (1986). In what was arguably Woody Allen’s best ensemble piece, Caine was tenderly sympathetic as a cultured accountant who becomes lovestruck by his wife’s sister (Barbara Hershey), who is herself trapped in a suffocating relationship. Back in London, Caine gave a mesmerizing performance as a contemptible mob boss in Neil Jordan’s “Mona Lisa” (1986). Any discussion of Caine’s work during the 1980s should mention the actor’s theory that for every five films, you need one standout picture in order to survive. He knew from experience, having dodged the bullet several times. 1987’s “Jaws: The Revenge” and ’88’s “Bullseye” definitely fell into the clunker category, but Caine bounced back quickly with a Golden Globe-winning performance in the miniseries “Jack the Ripper” (CBS, 1988). Ever a delight when he returned to comedy, Caine’s sophistication paired nicely with the broad antics of Steve Martin in 1988’s classic con men comedy, “Dirty Rotten Scoundrels” (1988).

By the 1990s, Michael Caine was again living in London and enjoying his status as an elder statesman of the cinema. For the first time since prior to becoming a film star, he appeared in a number of television projects, starring in 1990’s “Jekyll & Hyde” (ABC) and producing and starring in HBO’s spy drama “Blue Ice” (1993). He made a rare family film appearance as Scrooge in “A Muppet Christmas Carol”(1992), before reprising an aging Harry Palmer in Showtime’s original “Bullet to Beijing” (1995). If one mercifully overlooked the lackluster Steven Seagal vehicle “On Deadly Ground” (1994), Caine could be said to have made a most auspicious return to the big screen in his excellent but little seen performance as a ruthless safe cracker in “Blood & Wine” (1996). Instead, the film adaptation of the West End hit “Little Voice” (1998) proved to be Caine’s so-called comeback. As Ray Say, a Northern seaside town-dwelling talent scout whose London accent divulges his washed up status, the actor gave a stand-out performance in a film brimming with exceptional acting. Always keeping Ray Say’s pathetic desperation just below the surface until the end, Caine reached new heights in an already remarkable career. His show-stopping performance of “It’s Over” was nothing short of breathtaking, so it was not surprising that the legendary actor should win that year’s Golden Globe.

Caine’s big screen renaissance also included a fifth Oscar nomination and second win for Best Supporting Actor in Lasse Hallstrom’s “The Cider House Rules” (1999). Caine was back at the top of his game as a New England orphanage-running abortionist, and it was the actor’s keen subtlety that saved what might have been a treacly sentimental parable into something of moving relevance. The 66-year-old actor celebrated his latest landmark by taking a year off for the first time in his life since he began working at age 16. He wrote and released the entertaining autobiography What’s It All About? and decided to retire. For Caine, retirement meant taking small supporting roles as they interested him, but passing on leads that would take months to shoot and involve rigorous promotional tours. Still, to Caine, essentially retirement still meant appearing in two or three movies a year. He took a small role in the pointless Stallone-helmed remake of his early hit “Get Carter” (2000), and likewise paid homage to the cheeky spy dramas he helped popularize in “Austin Powers in Goldmember” (2002), playing the equally randy father of Mike Myer’s “shagadellic” secret agent.

Caine “came out of retirement” in 2002 and earned some of the best acting notices of his career for playing a British journalist covering the early days of Vietnam’s revolt against the French government in Graham Greene’s “The Quiet American.” He earned another Best Actor Academy Award nomination and went back to smaller roles with “Batman Begins” (2006), the stylish period thriller “The Prestige” (2006), and Alfonso Cuarón’s apocalyptic “Children of Men” (2006).

In 2007, Caine again revisited an earlier triumph with an updated version of 1972’s “Sleuth,” playing the aging writer role that had been Laurence Olivier’s and Jude Law in Caine’s original role as the young upstart vying for the writer’s wife. Despite the screenplay by Caine’s old friend Harold Pinter and direction by Kenneth Branagh, the overwrought film lacked the allure of the original. Law had previously starred in a 2004 remake of “Alfie,” but like most remakes of Caine’s prime work, it paled in comparison.

All actors had their side investments and pet projects, and for Michael Caine it was being a restaurateur. Caine, at one time, had partnerships in five restaurants, including his first venture, Langan’s Brasserie in London and the English-style grille Shepherd’s. The actor took an active role in running the businesses and could frequently be seen dining under his own awnings. He eventually sold all of his restaurant interests, but added another title to his long resume in the summer of 2007 when he released the CD Cained, a collection of chill-out tracks. Though he was admittedly far north of the electronica music’s demographic, Caine was a big fan of chill-out music and after years of making compilations for friends, he was encouraged by his friend Elton John to release his own collection of favorites.

Caine’s body of work was recognized in 1999 with an Evening Standard British Film Awards Lifetime Achievement Award. The following year, he was knighted by British Prime Minister Tony Blair and given a Lifetime Achievement Award from the UK Empire Awards. The National Board of Review honored Caine with a Career Achievement Award and the San Sebastian Film Festival recognized the actor with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000. The Film Society of Lincoln Center honored Caine with a star-studded Gala Tribute in 2004. Caine accepted his honor with the expected witty charm: ”I’ve been practicing humility all day. It’s very difficult for someone who’s been an actor for 40 years.”