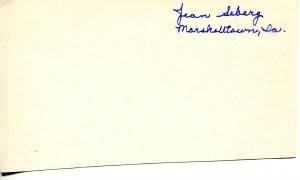

Jean Seberg had an unsual career. She was selected at an early age to star in Otto Preminger’s film of G.B. Shaw’s “St Joan” in 1957. She filmed for Preminger again in “Bonjour Tristesse” in France where she also made “Breathless”. She made her home in France for several years. In 1966 she returned to Hollywood to film “Moment to Moment” with Honor Blackman and “Airport” opposite Burt Lancaster in 1970. She died in 1979.

Jean Seberg was a gamine, blonde actress who landed the title role in Otto Preminger’s “Saint Joan” (1957) after a much-publicized contest involving some 18,000 hopefuls. She was best-known, however, for her contribution to New Wave cinema. The fresh-faced Iowan started acting in high school, but was a completely unknown 17-year-old when Preminger whisked her off to England. “Saint Joan” and its star were critically slammed, but Preminger went on to star her again in the soap opera “Bonjour Tristesse” (1958), which was scandalous and “modern” enough to buoy Seberg’s career.

After the silly but popular British comedy “The Mouse That Roared” (1959), Seberg was cast in Jean-Luc Godard’s landmark New Wave feature “A Bout de souffle/Breathless” (1959), which brought her renewed international attention. As an American in Paris, selling papers on the streets and romancing wanted criminal Jean-Paul Belmondo, she gave a careless, modern and very hip performance. Still, Seberg had to struggle through five unremarkable features before turning in a memorable performance as a schizophrenic in the title role of Robert Rossen’s “Lilith” (1964).

Seberg hopped back and forth from America to Europe, making a total of 30 films, although only a few of them were remarkable. In Mervyn LeRoy’s “Moment to Moment” (1966), she was a professor’s bored wife who drifts into an affair with murderous results. Seberg was another cheating wife in Irvin Kershner’s “A Fine Madness” (also 1966) and played a woman sold to a hard-drinking prospector (Lee Marvin) in Joshua Logan’s musical “Paint Your Wagon” (1969). Seberg was the passenger relations expert in the all-star blockbuster “Airport” (1970) and a woman going mad in Northern Africa in “Ondata di Calore/Dead of Summer” (1970). Her last feature was “Die Wildente/The Wild Duck” (1976), a German-language version of the Henrik Ibsen play. Seberg made her only US TV appearance in the ABC movie “Mousey” (1974), which co-starred Kirk Douglas and silent film veteran Bessie Love.

Seberg’s private life was far from happy. She was married four times: to Francois Moreuil (1958-60), who directed her in “La Recreation/Playtime” (1961); to Romain Gary (1962-70), who featured Seberg in “Les Oiseaux vont mourir au Perou/Birds in Peru” (1968); to Dennis Berry (1972-78), who helmed “Le Grande delire” (1975); and to Algerian-born Ahmed Hasni (1979), although she was not officially divorced from Berry. She supported the Black Panthers in the 1960s and early 70s, and when she miscarried Gary’s child in 1970, the FBI spread press stories that the baby’s father had been a Black Panther leader in an attempt to ‘neutralize’ her and destroy her career. Seberg, never very emotionally stable, attempted suicide almost yearly on the anniversary of her miscarriage. She was found in the back seat of her car, dead of a drug overdose, in Paris on September 8, 1979. Gary took the FBI to task publicly, and the bureau eventually admitted its complicity. In 1996, she was the subject of the independent film “From the Journals of Jean Seberg”, in which she was portrayed by Mary Beth Hurt

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.