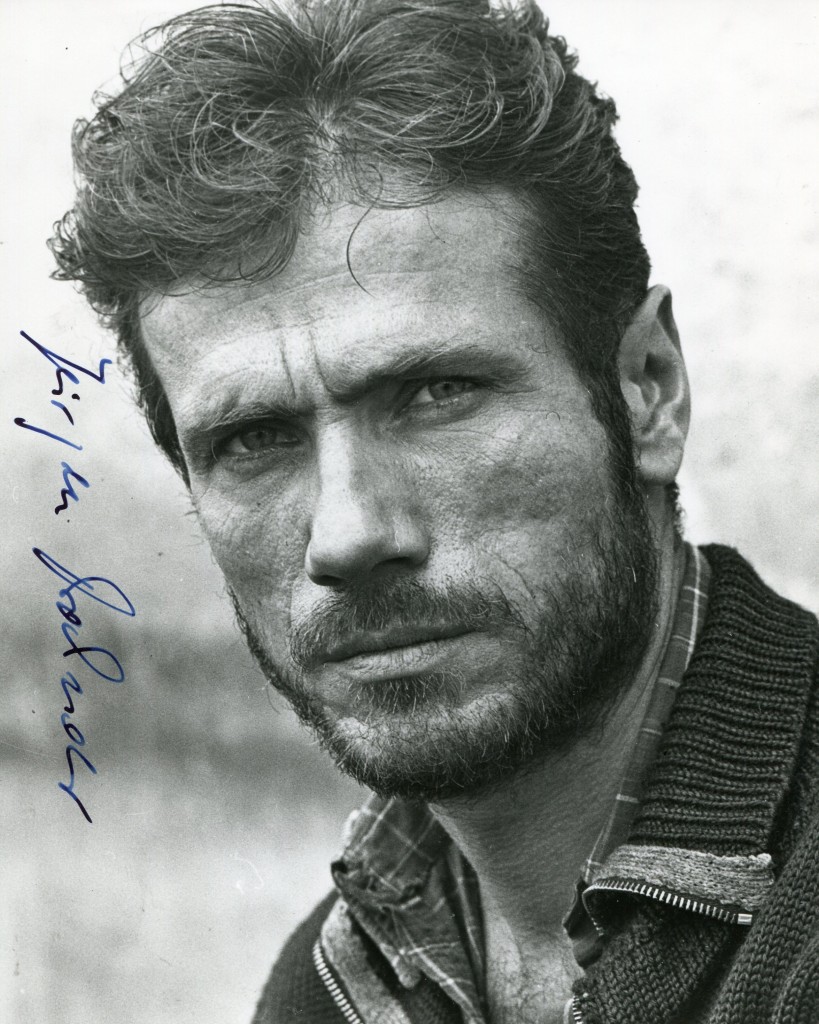

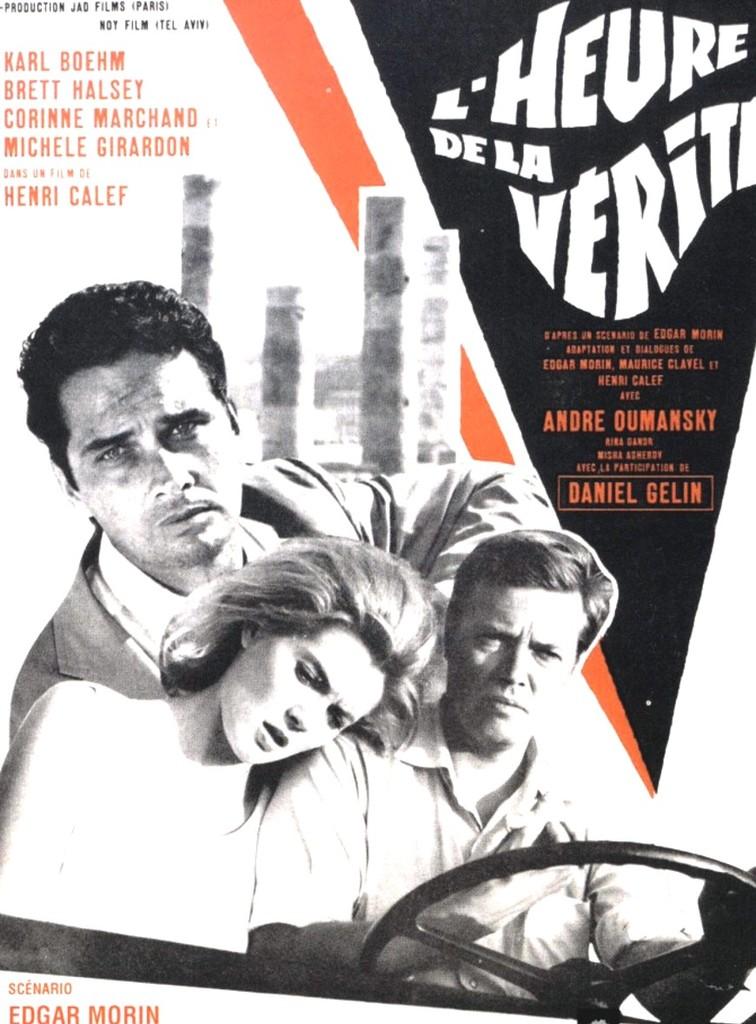

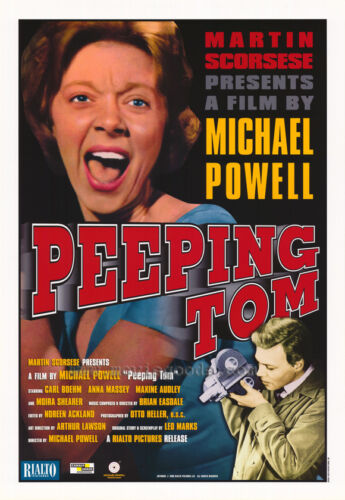

Karlheinz Boehm was born in 1928 in Darmstadt in Germany. He is the son of the famous conductor Karl Boehm. He palyed the Emperor Franz Josef opposite Romy Schneider in the three “Sissi” films in the 1950’s. He went on to make “Peeping Tom” for the famous British director Michael Powell in 1960. It was harshly reviewed when it first was released but is now regarded as a classic of repressed violence. He made “Come Fly With Me” with Dolores Hart in 1963. In his later years he has been very active in international charity work. He died in 2014.

His Wikipedia entry:

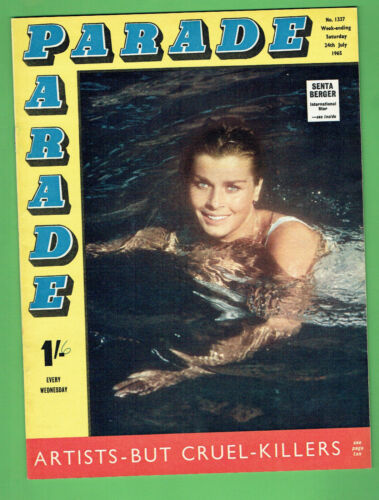

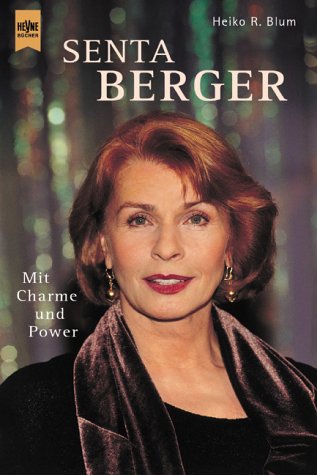

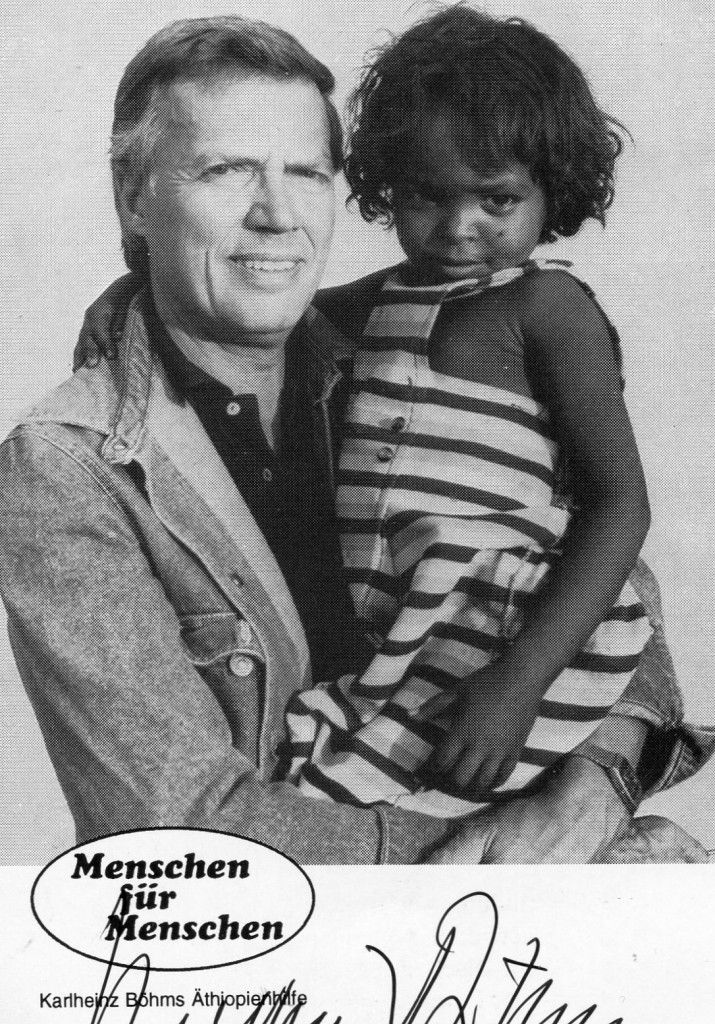

Karlheinz Böhm (born 16 March 1928 in Darmstadt), sometimes referred to as Carl Boehm or Karl Boehm, is an Austrian actor and the only child of soprano Thea Linhard and conductor Karl Böhm. Böhm took part in 45 films and became famous in Germany for his role as Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria in the Sissi trilogy and internationally for his role as Mark, the psychopathic protagonist of Peeping Tom, directed by Michael Powell. He is the founder of the trust Menschen für Menschen (“Humans for Humans”), which helps people in need in Ethiopia. He also received the Ethiopian honorary citizenship in 2003.

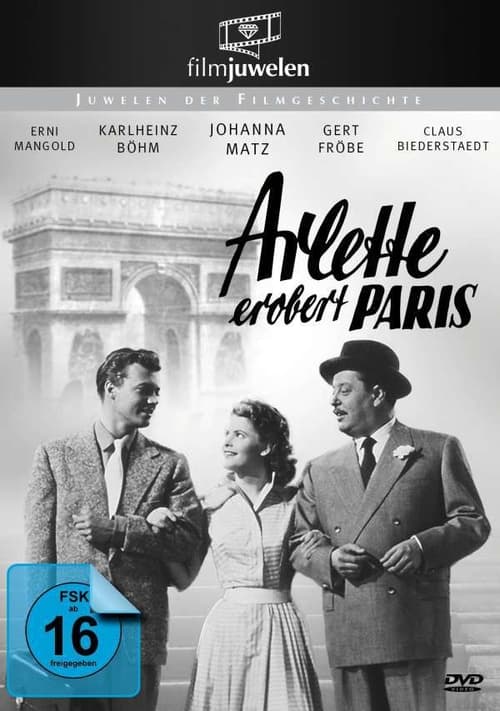

Having two citizenships, he sees himself as a world citizen: His father was born in Graz, his mother in Munich and today he lives in Grödig near Salzburg. He spent his youth inDarmstadt, Hamburg and Dresden. In Hamburg he attended elementary school and the Kepler-Gymnasium (a grammar school). A faked medical certificate[citation needed] enabled him to emigrate to Switzerland in 1939, where he attended the Lyceum Alpinum Zuoz, a boarding school. In 1946, he moved to Graz with his parents, where he graduated from high school the same year. He originally intended to become a pianist but received poor feedback when he auditioned. His father urged him to study English and German language and literary studies, followed by studies of history of arts for one semester in Rome after which he quit and returned to Vienna to take acting lessons with Prof. Helmut Krauss. From 1948 to 1976 he worked as a successful actor in about 45 films and also in theatre. With Romy Schneider, he starred in the Sissi trilogy as the Emperor Franz Joseph which limited him to one specific genre as an actor.

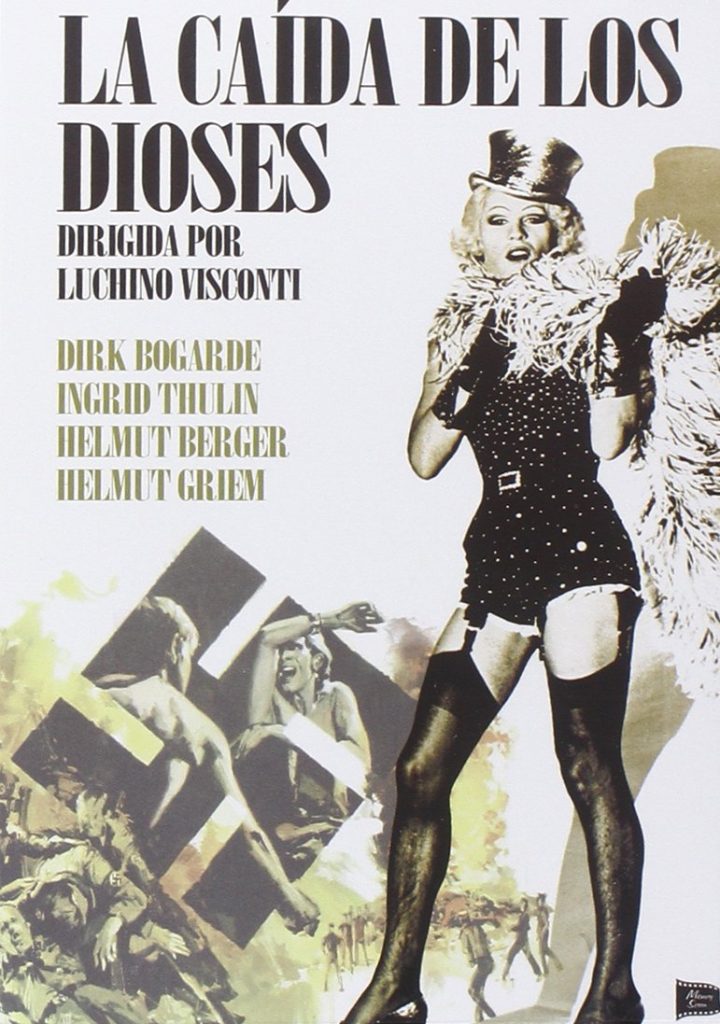

He made three notable U.S. films in 1962. He played Jakob Grimm in the 1962 MGM–Cinerama spectacular The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm and Ludwig van Beethoven in the Walt Disney film The Magnificent Rebel. (The latter film was made especially for the Disney anthology television series, but was released theatrically in Europe.) He appeared in a villainous role as the Nazi-sympathizing son of Paul Lukas in the MGM film Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, a Technicolor, widescreen remake of the 1921 silent Rudolph Valentino film.

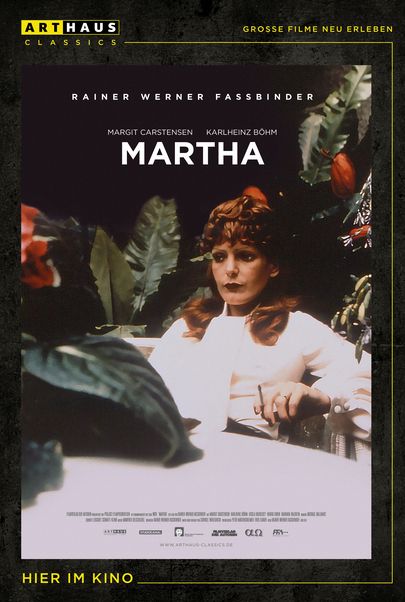

Between 1974 and 1975, Böhm appeared prominently in four consecutive films from prolific New German Cinema director Rainer Werner Fassbinder: Martha, Effi Briest, Faustrecht der Freiheit (aka Fistfight of Freedom or Fox and His Friends), and Mutter Küsters’ Fahrt zum Himmel (Mother Küsters’ Trip to Heaven).

Bohm’s voice acting work has included narrating his father’s 1975 recording of Peter and the Wolf by Prokofiev and in 2009 as the German voice for Charles Muntz, villain in Pixar‘s tenth animated feature Up.

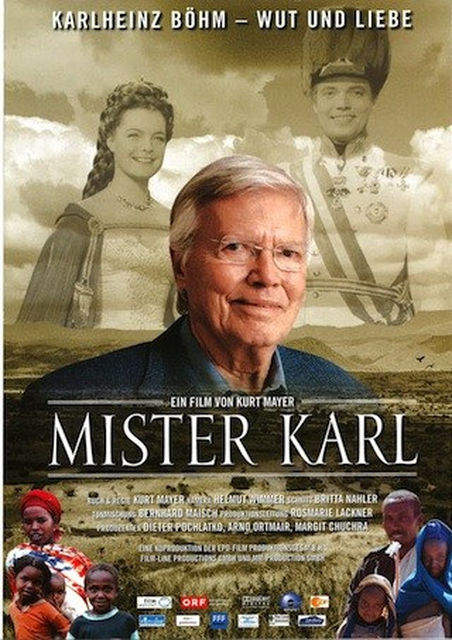

Since 1981, when he founded Menschen für Menschen (“Humans for Humans”), Böhm has been actively involved in charitable work in Ethiopia, for which in 2007 he was awarded the Balzan Prize for Humanity, Peace and Brotherhood among Peoples. Karlheinz Böhm has been married to Almaz Böhm, a native of Ethiopia, since 1991. They have two children, Nicolas (born 1990) and Aida (born 1993). Böhm has five more children from previous marriages, among them, the actress Katharina Böhm (born 1964). In 2011 Almaz and Karlheinz Böhm were awarded the Essl Social Prize for the project Menschen für Menschen.[1]

His Wikipedia entry can be accessed online here.

“Guardian” obituary:

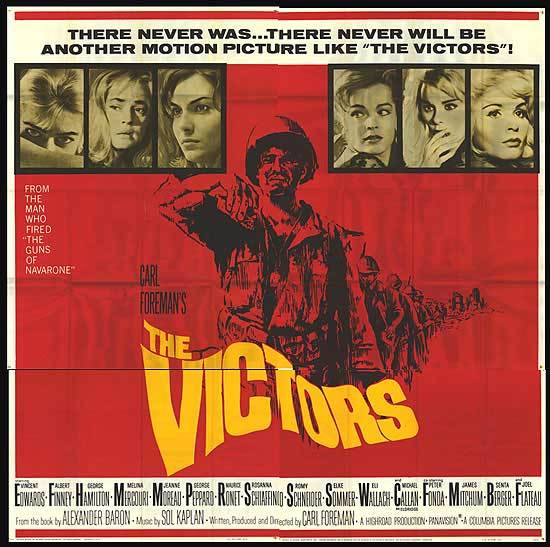

Among contrasting roles in the career of the actor Karlheinz Böhm, who has died aged 86, were a romantic portrayal of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria in the hugely popular trio of Sissi films (1955, 1956, 1957), the creepy title role in Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and unsympathetic characters in the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder in the 1970s. In addition, as befitted the son of the great Austrian conductor Karl Böhm and the soprano Thea Linhard, he portrayed Schubert in Blossom Time (1958) and Beethoven in The Magnificent Rebel (1962).

Born in Darmstadt, Germany, where his father had recently been appointed director of music, Böhm studied philosophy at the University of Graz, Austria. Although his parents arranged for him to take piano lessons at an early age, he was not interested in a musical career, and instead pursued his passion for acting. So, in 1948, he went to Vienna to work as assistant to the director Karl Hartl on The Angel With the Trumpet, in which he also had a bit part Böhm’s first leading role was in 1952 in Alraune (Mandragore), the fifth version of Hanns Heinz Ewers’ novel of a child born to a prostitute by artificial insemination from a hanged man, who grows up to be a soulless femme fatale. Böhm, boyishly naive, falls in love with Alraune (Hildegard Knef), the creation of his mad scientist uncle (Erich von Stroheim). It began a series of roles for Böhm as a handsome, rather wooden juvenile lead in a number of insignificant films during a particularly fallow period of German cinema. Then came Sissi (1955), in which Böhm played Franz Joseph opposite Romy Schneider’s Princess Elizabeth of Austria. This was followed by Sissi, the Young Empress (1956) and Sissi: The Fateful Years of an Empress (1957). These kitschy Technicolor costume dramas, part operetta, part Hollywood-style biopic, proved immensely popular, and Böhm became a matinee idol.

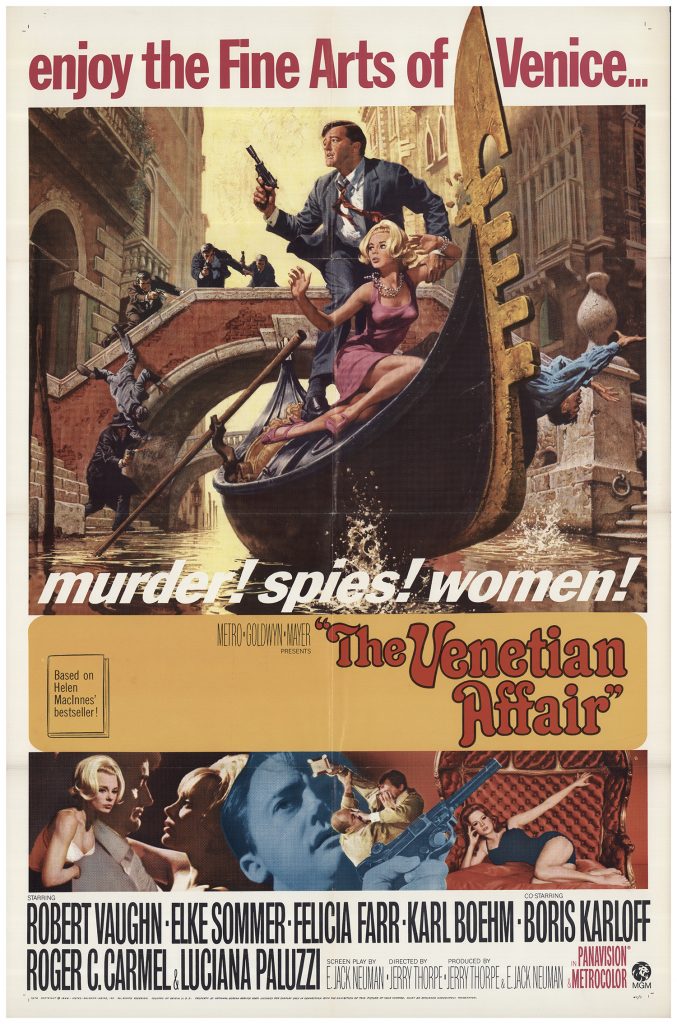

Therefore, many filmgoers were shocked to see him in Powell’s disturbing thriller Peeping Tom (1960) as a serial killer of women, who records the fear and dying contortions of his victims on film. Böhm (whose slight German accent went unexplained) was Mark Lewis, whose childhood is haunted by his sadistic psychologist father (played by the director). Powell cast Böhm, because he thought he might know what it was like to be the son of an overbearing father. Böhm’s performance is the more chilling because the character is ostensibly a normal young man with whom the audience can identify. The critical outrage against the film almost finished Powell’s career, while for Böhm it began a new phase in English-language films and more international recognition. He played a French journalist hanging around a seamy Soho strip club, in Too Hot to Handle (1960), featuring Jayne Mansfield; one of the storytelling brothers (the other was Laurence Harvey, very different in looks and accent) in The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962); and an SS officer in Vincente Minnelli’s leaden The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse (1962). It was for Walt Disney Productions that he appeared as a brooding and intense Beethoven in the highly fictionalised The Magnificent Rebel. One risible scene had Beethoven getting inspiration for the first notes of his 5th Symphony from the landlord rapping on his door to ask for the rent. Most of his subsequent films did little for his image, appearing as he did as charming villains in the fluffy Come Fly with Me (1963) – as a German baron using a flight attendant (Dolores Hart) for his smuggling plans – and the tepid spy spoof The Venetian Affair (1967). During the same period, he directed a few operas, including Elektra in Stuttgart and Tosca in Graz.

In 1968, a change came about the hitherto apolitical Böhm, prompted by the birth of the German student movement that year. “I was acting in Frankfurt at the time,” he recalled. “I was sitting in a trendy bar when a group of demonstrators went past. I couldn’t understand what made a bunch of young, well-off people take to the streets. But I started asking questions, and could see that we all have to take a moral and ethical stand.” A few years later, he met the radical film-maker Fassbinder, who deepened aspects of Böhm’s screen persona in four films. In Martha (1974), Böhm, as a brutal husband, brilliantly displays the sadism that was masked in Peeping Tom. He is a world-weary counsellor in Effi Briest (1975), a smooth antiques dealer in Fox and His Friends (1975) and a manipulative wealthy communist in Mother Küsters Goes to Heaven (1975).

In 1981, Böhm was a celebrity guest on the popular television game show Wetten, dass…? (Wanna bet?) and bet that fewer than one in three people watching would donate at least one deutschmark or one Swiss franc to Ethiopia, the world’s third-poorest country. As a result, he raised the impressive sum of 1.2m marks, and went on to establish the charitable organisation Menschen für Menschen (People for People), raising money for the people of Ethiopia. Ten years later, in 1991, Böhm married (as his fourth wife) Almaz Teshome, an Ethiopian archaeologist. She later served on the board of the charity, becoming its chair in 2011. Boehm was made an honorary Ethiopian citizen in 2001. “Because they have recognised I didn’t come as a stranger, to show them what they have to do to get out of their poverty,” he explained. “No. I tried to find out what the people are missing, and how they can help themselves. My heart has become deeply Ethiopian in the deepest sense of the word. I don’t live only for myself any more, but I live for other people.”

Among Böhm’s several awards was the Berlinale Camera at the 2008 Berlin film festival. He is survived by Almaz , their two children, and five other children from his previous marriages, who include the actor Katerina Böhm.

• Karlheinz Böhm, actor and charity campaigner, born 16 March 1928; died 29 May 2014