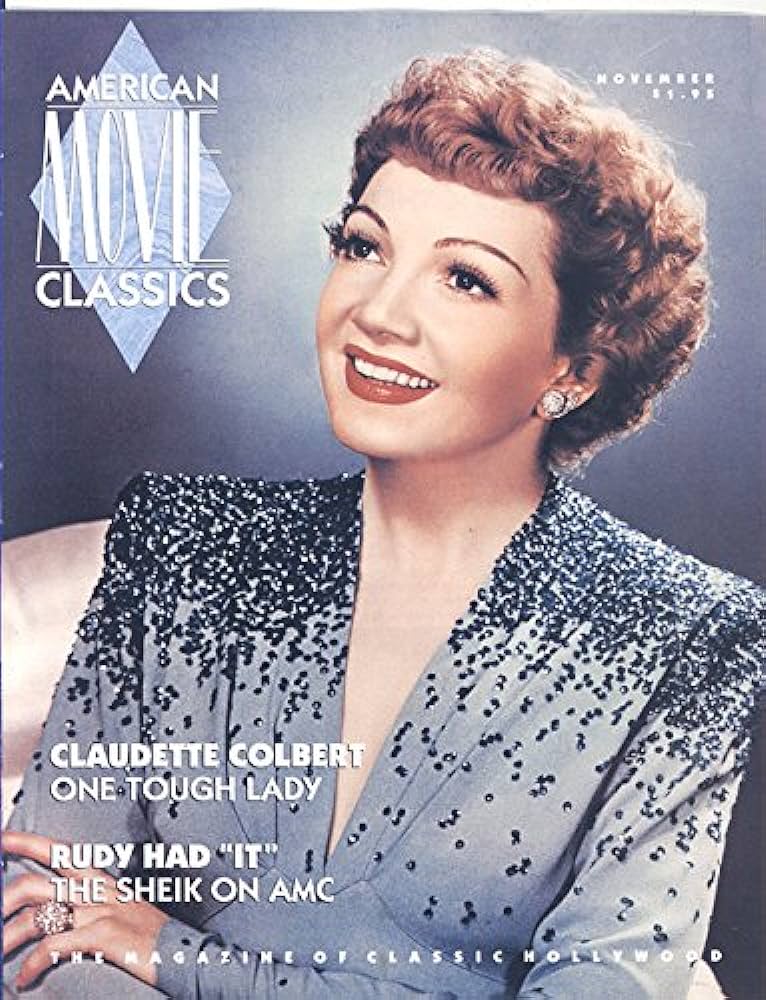

It is no accident, surely, that she flourished at that most European of studios, Paramount, home of Lubitsch and Chevalier, Mamoulian, Von Sternberg and Wilder. Her distinctive high-cheekboned beauty and the throaty individuality of her voice were complemented by superb comic timing and fine technical skill honed by an extensive apprenticeship in the theatre.

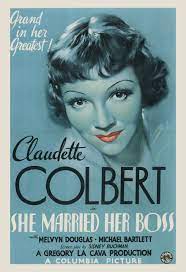

She could be warmly compassionate in romantic drama but was unsurpassable in sophisticated comedy. Many of her Thirties comedies with titles like I Met Him In Paris and She Married Her Boss are minor trifles elevated by her presence, and at least three of her comedies, It Happened One Night, Midnight and The Palm Beach Story are among Hollywood’s greatest ever. It is a mark of the respect in which she was held by film-makers that throughout her career sets were built and scenes directed in order to favour the left side of her face, since she was convinced that her right profile was unflattering.

After a long Hollywood career she returned with great success to the theatre, and was 82 years old when she last performed in London, starring with Rex Harrison in Frederick Lonsdale’s Aren’t We All?

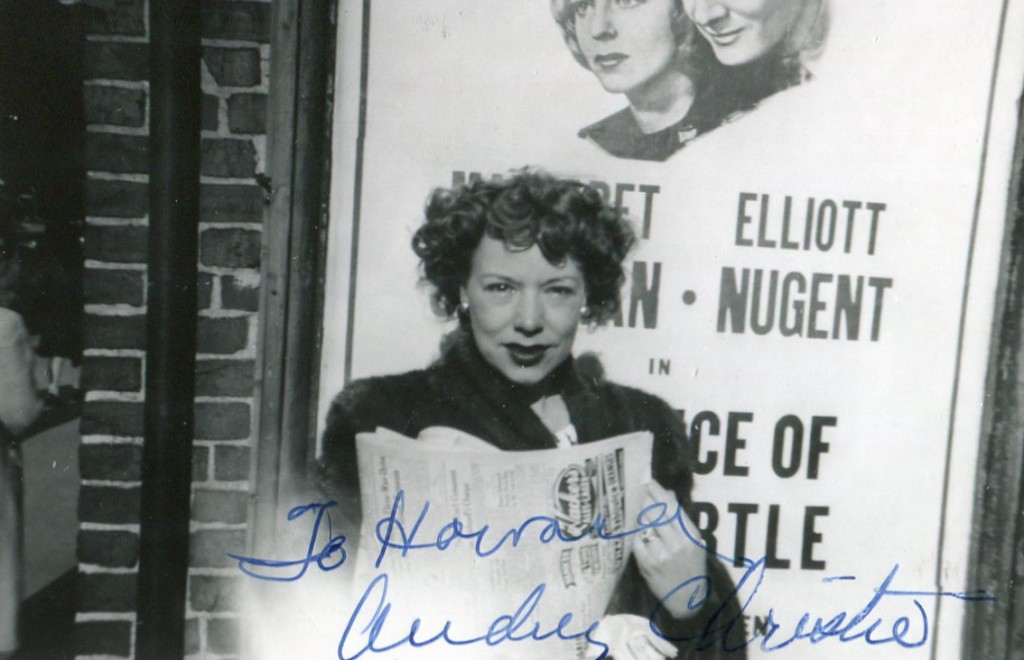

Born Lily Claudette Chauchoin in Paris in 1903, she was seven when her family emigrated to New York. Though she did some acting in college, her primary interest was fashion design – later she was to become one of Hollywood’s best-dressed stars – and she was studying fashion when at 20 she so impressed the writer Anne Morrison at a party that she offered her a three-line role in her play The Wild Westcotts.

Over the next five years, she appeared in a succession of mostly short- lived shows, learning from experience and studying the actors she worked with. “Acting schools are all very well,” she said later, “but the way to learn acting is to act, observe others, learn from your betters, learn what not to do – and above, all, to keep working.” The actor Leslie Howard, with whom she had a brief relationship in 1924, encouraged her and persuaded his friend the producer Al Woods to put her under contract but, despite personally good notices, she did not get into a major hit until The Barker (1927) with Walter Huston and Norman Foster.

She and Foster, later a Hollywood actor and director, were married the following year during the play’s London run. Colbert’s first film, For the Love of Mike, made during The Barker’s Broadway run, was directed by Frank Capra but cheaply produced and provoked Colbert to state that films were “off my list permanently”. She was particularly concerned that silent cinema failed to utilise one of her major assets, her voice. The advent of talkies changed her attitude, and in 1929 she signed a Paramount contract.

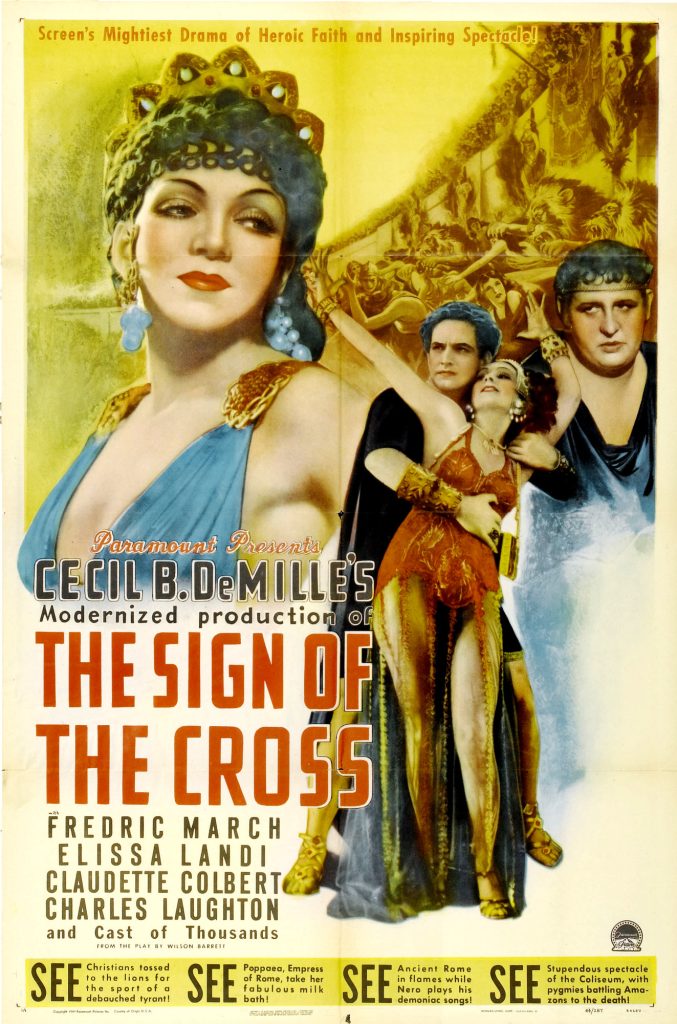

Only two of her first 15 movies – The Big Pond (1930) and The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), both co-starring Maurice Chevalier – were better than mediocre, and she was grateful when Cecil B. De Mille asked her to play “the wickedest wo-man in the world”, Poppaea, wife of Nero, in The Sign of the Cross (1932). Her performance was acclaimed, while her bath in asses’ milk received immense publicity and has become a famous scene in Hollywood history.

Her career had slumped again when Columbia fortuitously offered her the role of a runaway heiress in It Happened One Night (1934) after Constance Bennett, Miriam Hopkins and Myrna Loy had turned it down. Colbert accepted the role only because it gave her the chance to work with Clark Gable, who had been forced by his studio, MGM, to do the film.

Neither star initially expected much of the low-budget comedy which won five Oscars. Colbert was in fact boarding a train for New York on the night of the ceremony when she was stopped and rushed back to accept her Best Actress award from Shirley Temple. “It did wonders for my image and my private morale,” she said later.

Two more big hits consolidated her status. She played the title role in De Mille’s lavish if largely inaccurate Cleopatra (1934), then elected to star at Universal in a trenchant study of racial intolerance, John Stahl’s Imitation of Life (1934), based on Fannie Hurst’s novel about a young widow who becomes a millionairess marketing the pancake recipe of her black friend (Louise Beavers). While the widow and her daughter move into society, the friend insists on keeping in the background, and when her light-skinned daughter, who faces exclusion and prejudice where her counterpart has privilege and opportunity, tries to pass for white and disowns her mother tragedy follows.

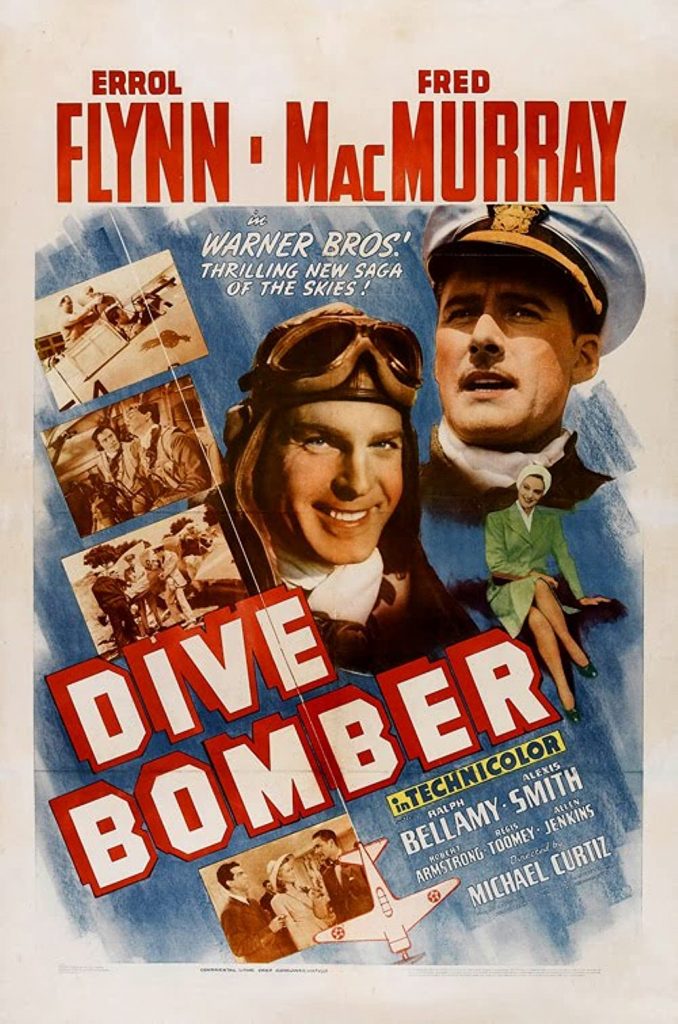

Colbert was now – in 1935 – named one of the top 10 money-making stars, a position she was to hold again in 1936 and 1947. Fred MacMurray had his first major role in her next film, The Gilded Lily (1935), and always credited Colbert for the help she gave him. “She was so patient with me,” he said, “and I learnt more from her about screen acting than I have ever picked up since.” (They were to make six more films together.) Charles Boyer, co-star of Colbert’s next film, Private Worlds (1935), and not yet fully conversant with the English language, would also acknowledge the support he received from the actress, who won a second Oscar nomination for her performance as a psychiatrist in this grim story of mental illness.

Colbert’s first marriage ended in 1935 while she was making Gregory LaCave’s She Married Her Boss. Her co-star Melvyn Douglas later said, “Foster seemed a nice guy, but rather on the slow and stodgy side for a dynamo of sensuality like Claudette.” The same year she married an ear, nose and throat doctor, Joel Pressman, who remained her husband until his death in 1968.

Colbert’s role in Frank Lloyd’s Under Two Flags (1936), based on Ouida’s tale of the Foreign Legion, was an unusual one for her, that of the tempestuous camp-follower “Cigarette” who sacrifices herself for love of a soldier (Ronald Colman). For the same director she starred in Maid of Salem (1937), an account of the 1692 witch-hunts in Massachusetts. (Sixteen years later the playwright Arthur Miller dealt with the same subject more effectively in The Crucible.)

Colbert never seemed entirely comfortable in period pieces, and both audiences and critics were happy when she returned to modern comedy with I Met Him In Paris and Tovarich (both 1937), in which she and Charles Boyer were impoverished Russian nobility working as maid and butler in a Parisian household.

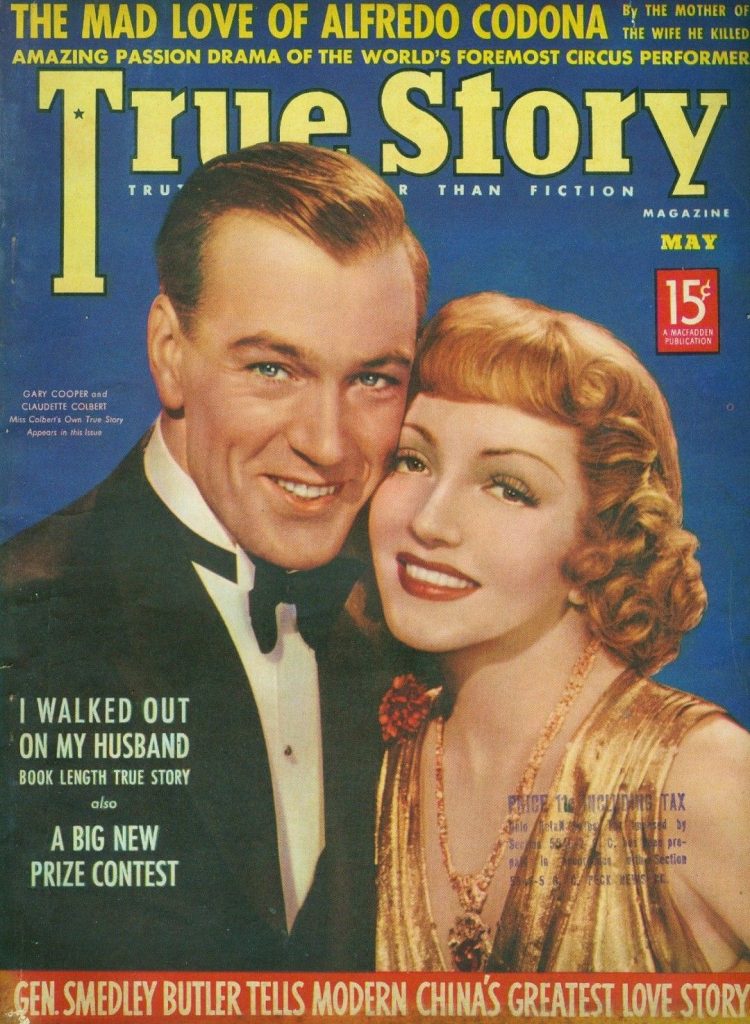

Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938), with a screenplay by Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett, based on a 1923 Gloria Swanson silent and directed by Ernst Lubitsch, was a disappointment. After a promising start in which Colbert meets Gary Cooper in a Riviera store where she is trying to buy pyjama bottoms while he is trying to purchase just the tops, it becomes contriv-ed and frantic rather than funny.

George Cukor’s Zaza (1939), in which Colbert sang several songs as a French music-hall star, was another failure, but preceded one of her greatest films, Midnight (1939), directed by Mitchell Leisen and brilliantly written by Brackett and Wilder. From the opening shot of Colbert discovered sleeping in a freight car wearing an evening gown and clutching her purse, this story of a stranded showgirl in Paris who gate-crashes a society soiree and gets involved in an increasingly complicated escapade when she is hired by a millionaire to lure a gigolo away from his wife, captivates with brittle wit, expert plotting and fine playing from a cast including John Barrymore and Mary Astor.

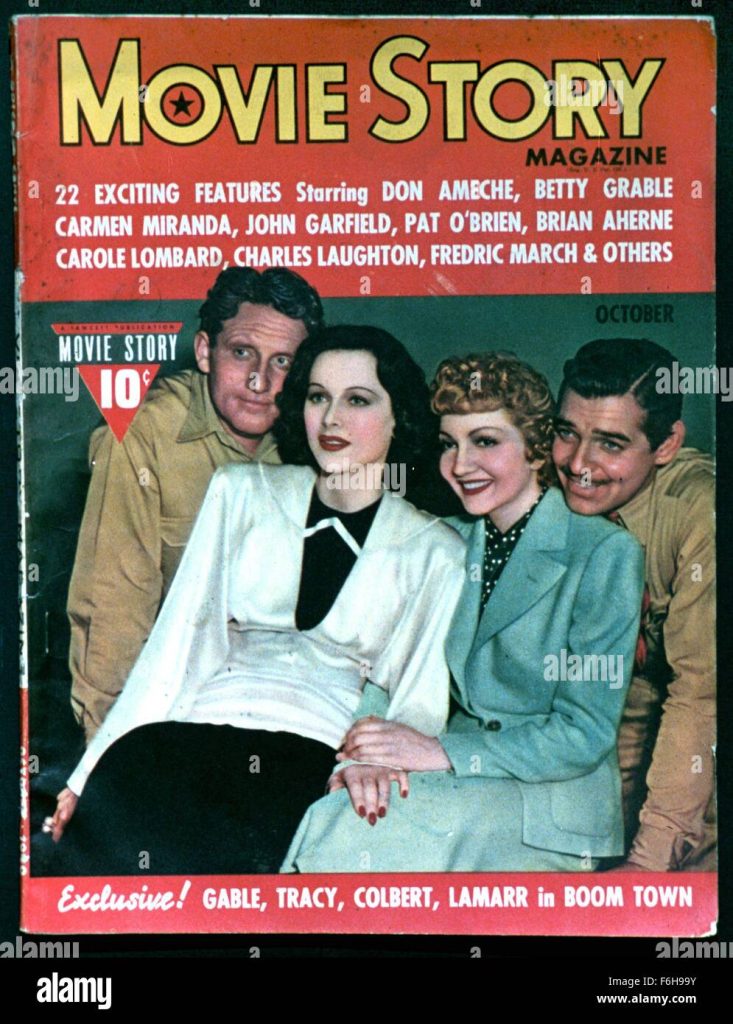

Colbert was basically miscast in John Ford’s Drums Along the Mohawk (1939), her first film in colour, as a farmer’s wife coping with rugged conditions and hostile Indians, and though Boom Town (1940) was one of her most popular films, due to its star-power of Gable, Colbert, Spencer Tracy and Hedy Lamarr, it was basically over-blown soap opera.

Set just after the Spanish Civil War, Leisen’s Arise My Love (1940) was the film the actress would cite as her own favourite and it has some splendidly romantic, dramatic and comic moments as Colbert, playing a reporter, pretends to be the wife of a condemned soldier of fortune (Ray Milland) to save him from a Spanish firing squad, then inevitably falls in love with him. Brackett and Wilder’s screenplay tried to keep pace with changing events in Europe (the story ends after the invasion of France) which resulted in some uneasy shifts of mood in an otherwise impressive work.

Better still was Henry King’s warmly charming piece of Americana Remember The Day (1941), in which Colbert gave a glowing performance as a school teacher who while visiting a now-famous former pupil recalls the past and her sweetheart who was killed in the First World War.

Preston Sturges’ The Palm Beach Story (1942) is one of the screen’s greatest screwball comedies and contains the sequence Colbert later cited as her favourite comic scene. Having left her husband to find a millionaire to finance his inventions, she is climbing into a train’s upper berth when she steps on the face and glasses of a rich passenger (Rudy Vallee).

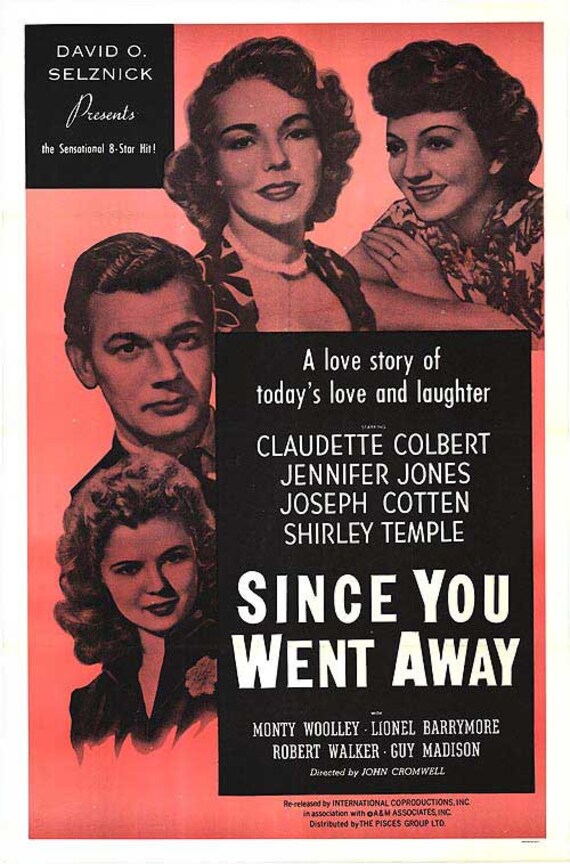

During the Second World War Colbert’s husband, Joel Pressman, became a navy lieutenant and she spent much time selling war bonds and working for the war effort. Two of her major films were effective wartime propaganda: So Proudly We Hail (1943), a tribute to the nurses in Bataan – though Colbert did not get along with her co-stars Paulette Goddard and Veronica Lake – and Since You Went Away (1944), the producer David O. Selznick’s ambitious three-hour tribute to the families at home.

Colbert considered hard before taking the role of the mother to two teenage girls, but it became one of her finest, most deeply felt performances, representing the women left to raise families while their husbands are at war. In one remarkably touching scene Colbert, who has taken a job at a munitions factory, converses with a refugee, now a naturalised American (Alla Nazimova). The director John Cromwell called Colbert “a great star at the height of her powers” and she received her third Academy Award nomination (losing to Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight).

This was to be the last occasion when a truly great performance and great film were to come together in her career – she unfortunately turned down Leisen’s offer to star in To Each His Own, feeling that its story of unwed motherhood was old-hat – Olivia de Havilland won an Oscar for the role. Later she was to withdraw from Capra’s State of the Union when he refused to meet her contractual demands that she finish work by 5pm each day, and lost the role of Margo Channing in All About Eve because of a back injury, a stroke of bad luck that she lamented for the rest of her career.

Instead she appeared in some mild comedies (Practically Yours, 1944, Without Reservations, 1946) and tepid dramas (Tomorrow is Forever, 1945, The Secret Heart, 1946). Tomorrow is Forever had in its favour some movingly intense scenes between Colbert and Orson Welles, while June Allyson, playing her first dramatic role in The Secret Heart, is another who later testified to Colbert’s generosity. “She sensed my insecurities,” wrote Allyson later, “and gave me the moral support and acting tips that made a world of difference.”

Colbert and Fred MacMurray had an enormous box-office hit with The Egg and I (1947) as a city couple trying to run a farm, but the slapstick (lots of falling about in the mud) was far from the sophistication Colbert purveyed so expertly. Jean Negulesco’s Three Came Home (1950) gave her a strong dramatic role as Agnes Newton Keith, a true-life American authoress captured when the Jap-anese invaded Borneo in 1941. Her scenes with Sessue Haya-kawa (as the cultured prison camp commander) were memorable in a gripping film which was too grim to be a major hit.

Colbert had appeared on radio regularly throughout her career, and in 1951 she made her television debut on The Jack Benny Show. Other appearances included The Royal Family of Broadway (1954), The Guardsman (1955) and Blithe Spirit (1956), with Noel Coward and Lauren Bacall.

In 1951 she also returned to the stage, with a tour of Noel Coward’s Island Fling (later known as South Sea Bubble). Though she and Coward were close friends, their temperaments clashed during this production, causing Coward to tell her “I’d wring your neck – if you had one.” She came to Britain to star with Jack Hawkins in The Planter’s Wife (Outpost in Malaya was its US title) based on the native terrorism being faced by rubber planters. The film was a big hit in this country.

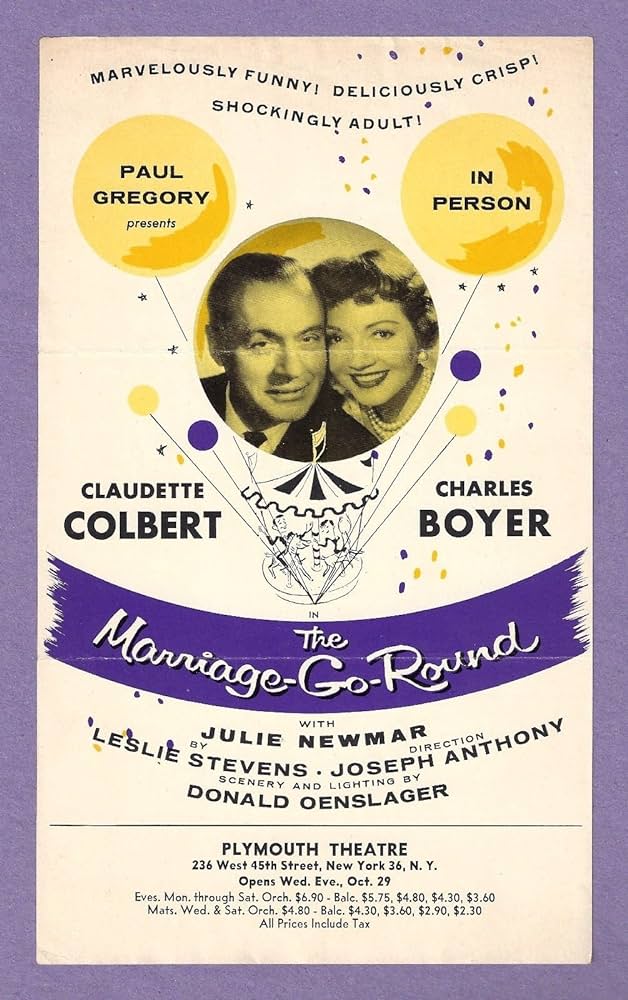

The following year Colbert went to France to play a mistress of Louis XIV in Sacha Guitry’s Si Versailles m’etait conte, a lavish but empty pageant. She returned to Broadway in 1955, replacing Margaret Sullavan in Janus, then in 1958 starred in a new play, Leslie Stevens’s The Marriage- Go-Round. The New York Times stated, “The comedy skill of the chief actors is incomparable – they are Charles Boyer and Claudette Colbert, making something gay and iridescent out of something small and familiar.” The play was a hit and Colbert won a Tony nomination.

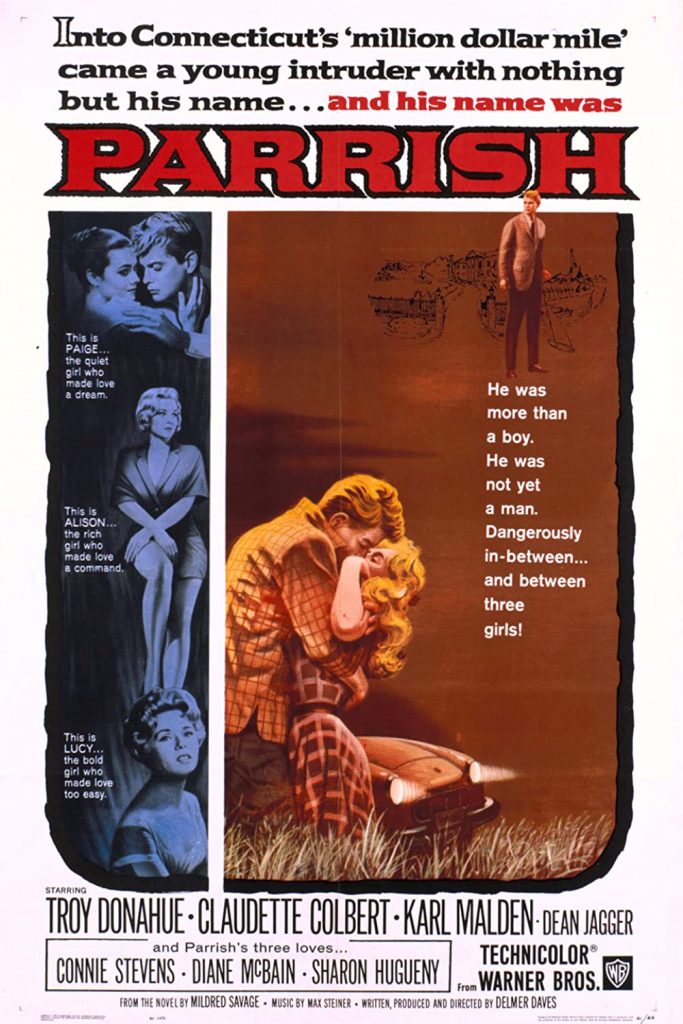

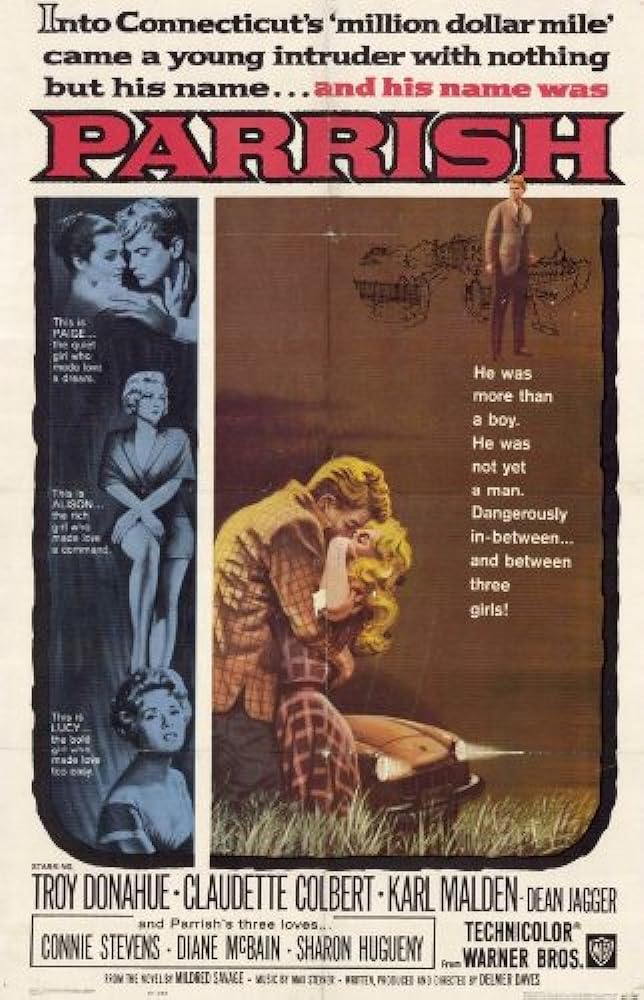

She made her last film in 1961, Delmer Daves’s Parrish, a turgid soap opera in which Colbert played the mother of Troy Donahue. She continued to make Broadway appearances, among them The Irregular Verb To Love (1963), The Kingfisher (1978) and A Talent For Murder (1981), then in 1984 returned to the London stage (for the first time since The Barker almost 60 years earlier) in Aren’t We All? Her charm and beauty again beguiled the critics and her professionalism allowed her to deal smoothly with the frequent fluffing by Harrison.

Over the last 30 years, she spent much of her time at the home she and her husband had bought long ago in Barbados, and she also had a flat in Paris and an apartment on the East Side of New York.

She remained active socially until recently, always elegantly dressed (one of her closest friends was the late Ginette Spanier, former directrice of the House of Balmain) and exuding bubbly effervescence. Asked what the key was to her ageless beauty, she replied: “Laughter – it’s the key to everything. To a day of gloom or despair, to happy work, to life.”

Tom Vallance

Lily Claudette Chauchoin (Claudette Colbert), actress: born Paris 13 September 1903; married 1928 Norman Foster (marriage dissolved 1935), 1935 Joel J. Pressman (died 1968); died Cobblers Cove, Barbados 30 July 1996.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.