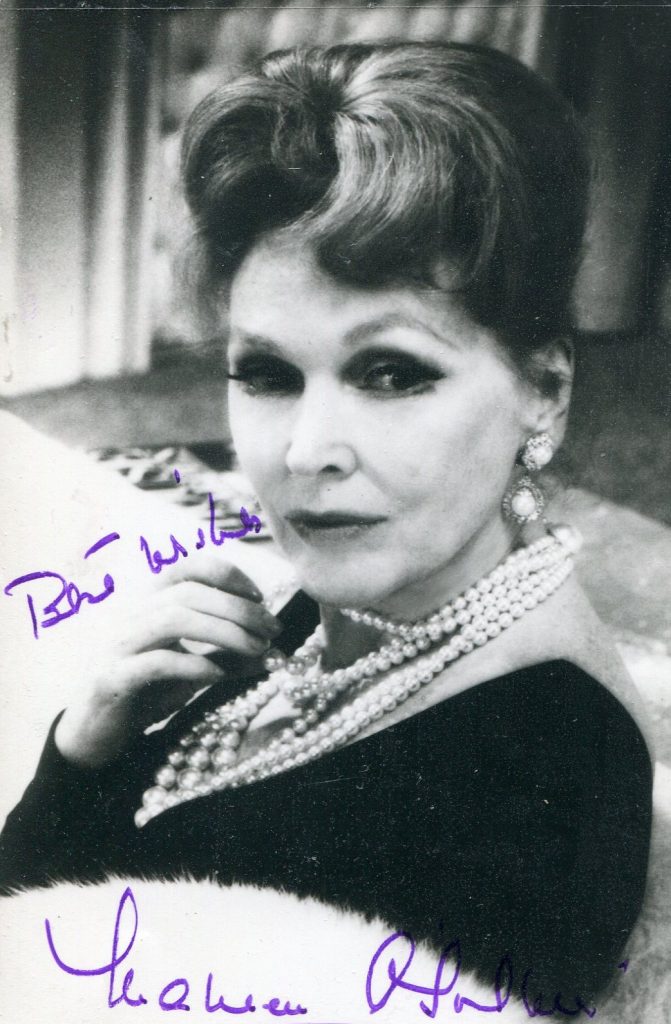

Maureen O’Sullivan obituary in “The Independent” in 1998.

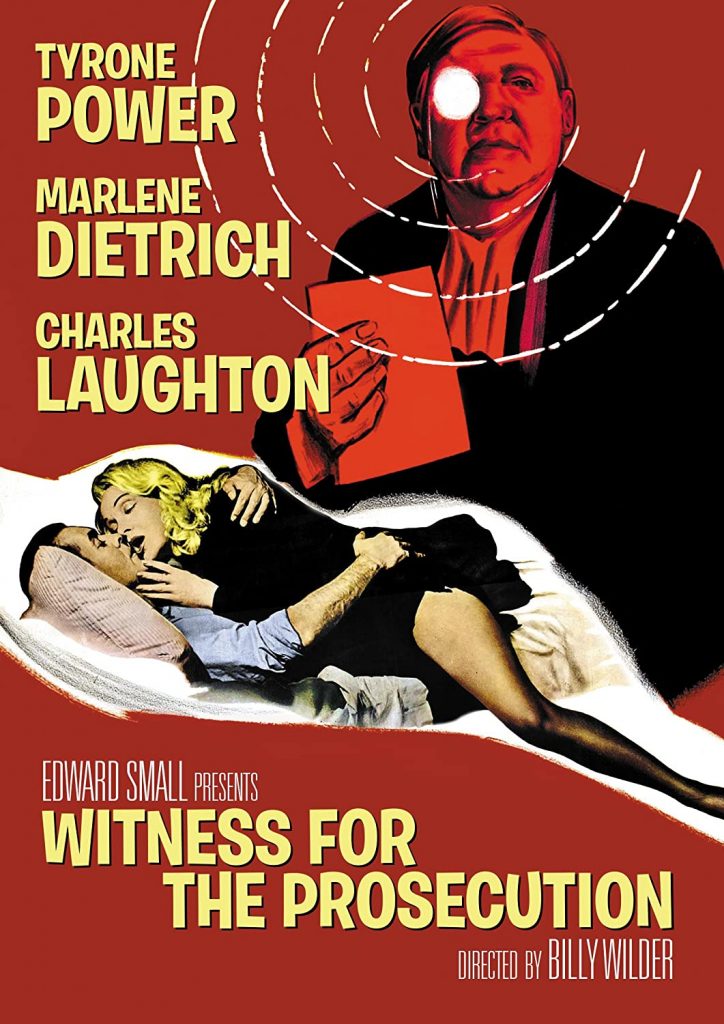

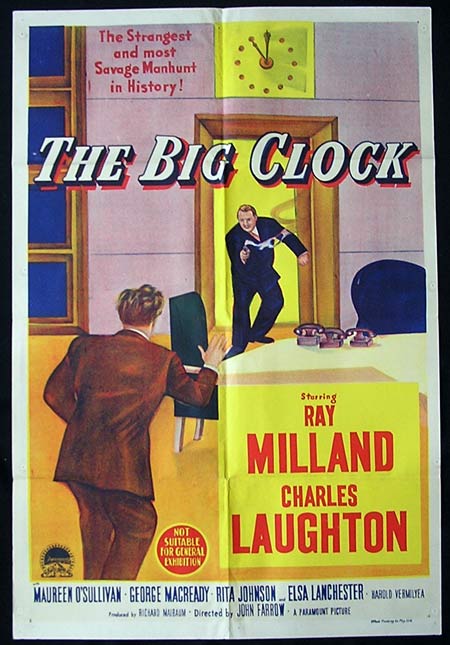

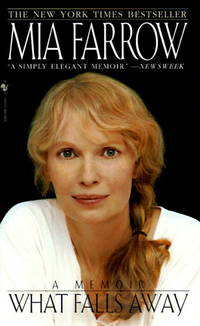

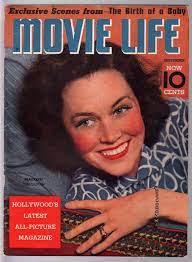

Maureen O’Sullivan was born in Boyle Co. Roscommon in 1911. She studied at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Roehampton outside London. One of her class mates was Vivien Leigh. In 1929 she met director Frank Borzage who was in Ireland. He brought Maureen O’Sullivan to Hollywood to make “Song O ‘My Heart” with the great Irish tenor John McCormack. In 1932 she starred in one of her most famous roles Jane to Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan in “Tarzan, the Ape Man”. In all she made six Trarzan films and she is regarded as the definite Jane. She had a contract with MGM and starred in such classics as “The Thin Man”, “A Day at the Races”, “Anna Karenina” and “David Copperfield” as Dora Spenlow. In 1942 she retired to rear her family. She had seven children in all. In 1948 she returned to film making in “The Big Clock” with Ray Milland and Charles Laughton which was directed by her husband the Australian John Farrow. She had a remarkably long career and made over 65 films over a 65 span. She died in 1998. Maureen O’Sullivan’s daughter is the actress and activist Mia Farrow.

“The Independent” obituary by Tom Vallance:THE DELICATELY beautiful, Irish-born actress Maureen O’Sullivan will be best remembered for two reasons – her performance as Jane in a string of Tarzan films opposite Johnny Weissmuller, and as the real-life mother of Mia Farrow. She memorably quipped, when told that Frank Sinatra was hoping to marry her daughter, “At his age, he should mary me.

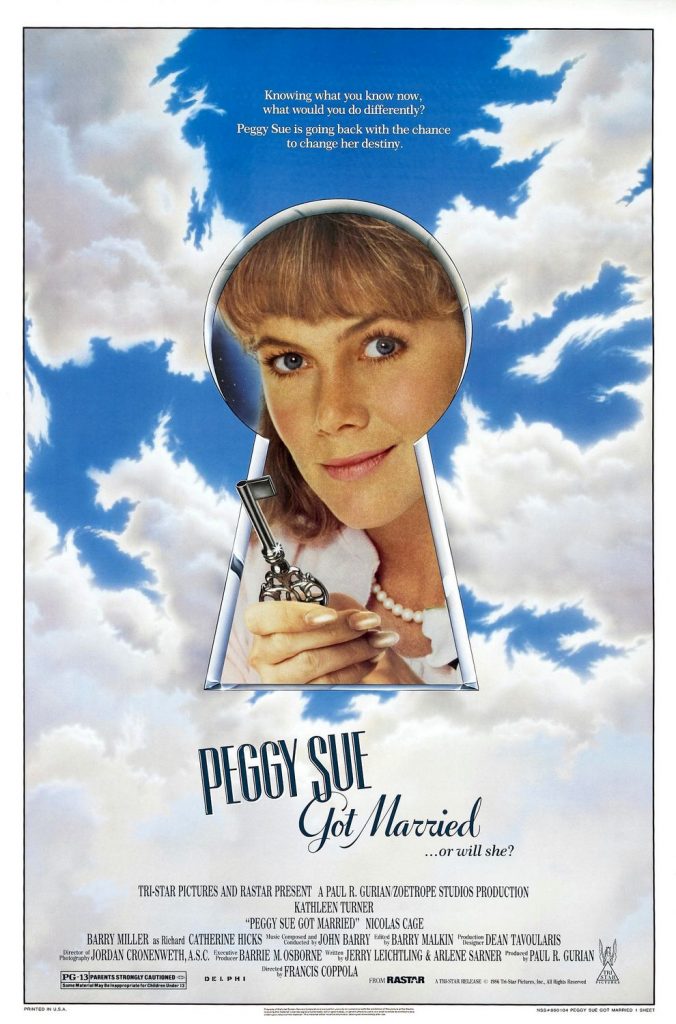

O’Sullivan’s own career was a long and distinguished one, including performances in such major Hollywood films as The Thin Man, Pride and Prejudice, The Barretts of Wimpole Street, Anna Karenina, A Day at the Races, The Big Clock, and more recently Hannah and Her Sisters, in which she played mother to her daughter Mia.

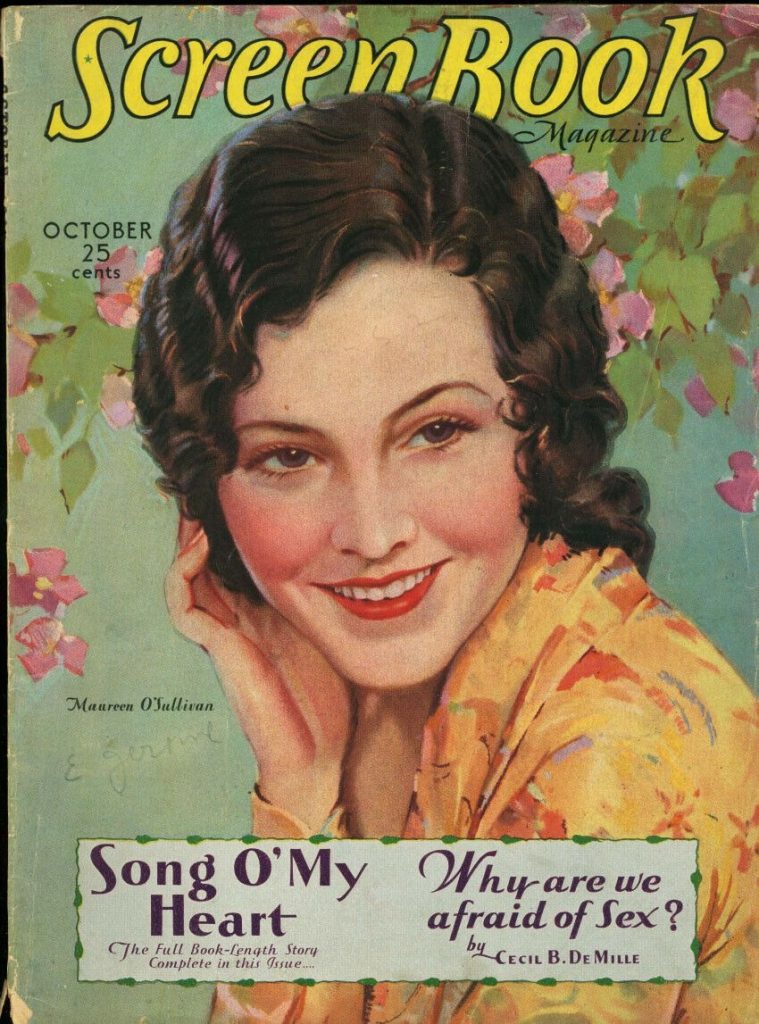

Born in Boyle, Ireland, in 1911, O’Sullivan had had no acting training when she was noticed by the director Frank Borzage at a dinner-dance of Dublin’s International Horse Show. He had the waiter send her a note: “If you are interested in being in a film, come to my office tomorrow at 11am”, and subsequently he cast her as the daughter of tenor John McCormack in Song O’ My Heart (1930), which was being partly filmed in Erin before completion in Hollywood.

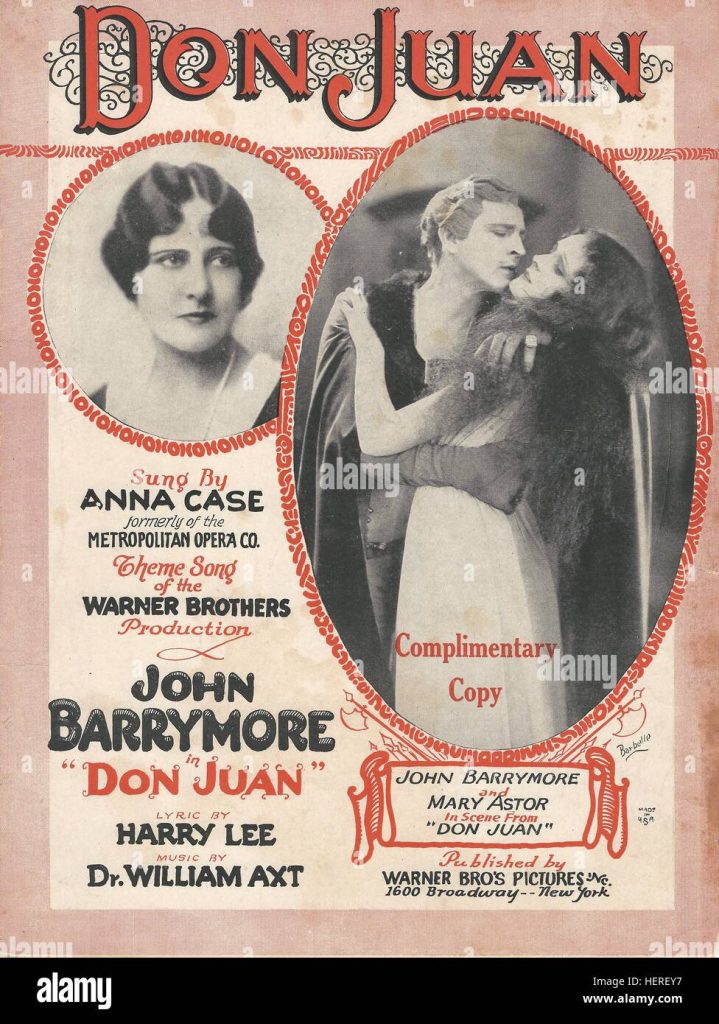

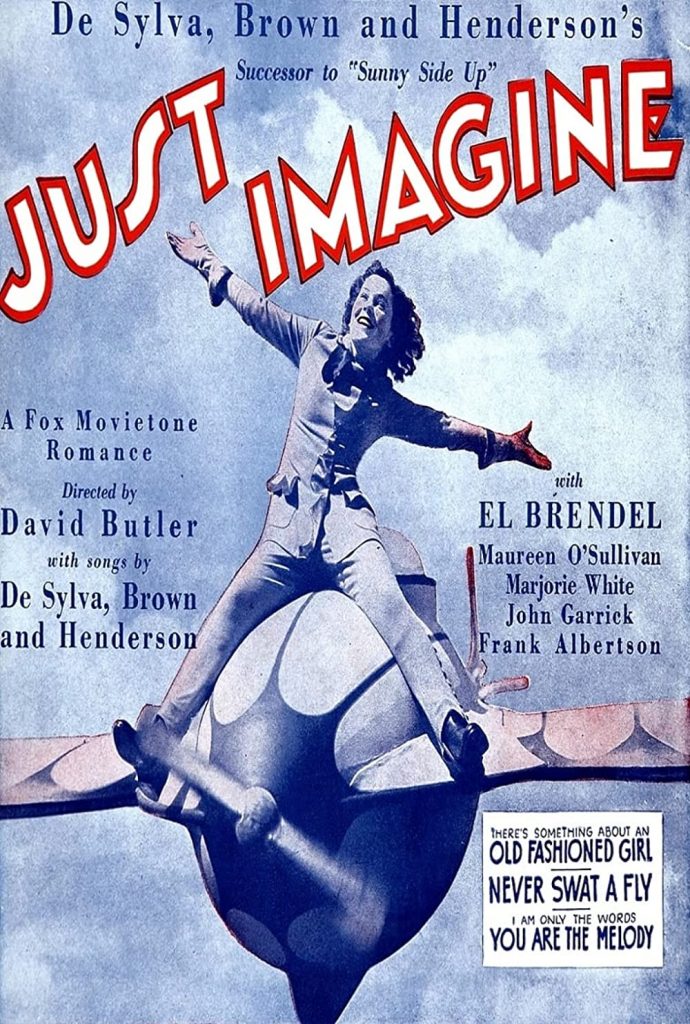

Though O’Sullivan’s inexperience was apparent, the film was a great success and the studio (Fox) gave the new actress a contract. Her next film was the futuristic musical, Just Imagine (1930), after which she was teamed with the studio’s top star Will Rogers in The Princess and the Plumber (1930). O’Sullivan later expressed dissatisfaction with her treatment by the studio, feeling that they used her as a threat to their top female star Janet Gaynor, who was on suspension for more money and a new contract. When Gaynor settled with the studio, O’Sullivan’s roles became smaller and the following year, her contract was terminated.

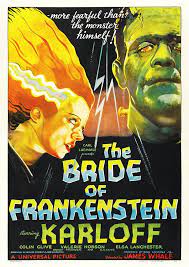

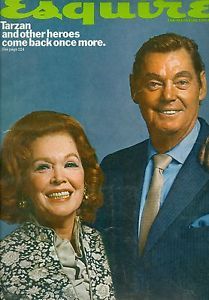

“I felt lonely, forsaken and unwanted,” she said later, but in 1932 she was signed to a contract by MGM and immediately cast as Jane in Tarzan, The Ape Man with the Olympic swimming champion Johnny Weissmuller as her co-star. In the Tarzan books, the heroine is Jane Porter of Baltimore, but MGM made her Jane Parker of London (O’Sullivan had been educated at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Roehampton, and her accent was totally convincing). The actress had not read any Tarzan books, and recalled that the author Edgar Rice Burroughs sent her copies of them. “He was a nice guy,” she said recently, “and thought Johnny and I were the perfect Tarzan and Jane, which is lovely.”

O’Sullivan, besides her attractiveness, brought a sense of humour plus an appealing blend of sophistication and innocence to the girl who teaches the jungle-bred hero how to speak, starting with “Tarzan . . . Jane” (not “Me Tarzan, you Jane” as commonly misquoted). The second of the series, Tarzan and His Mate (1934) is generally considered the best, matching the first in lyrical beauty and excelling it in excitement and dramatic impetus. “Everyone cared about the Tarzan pictures,” said O’Sullivan, “and we all gave of our best. They weren’t quickies – it often took a year to make one.”

What the critic DeWitt Bodeen called the “sweet paganism” of the first two films is missing from the later ones, partly because of pressures from moralist groups who objected to the scanty costumes, and in particularly a sequence in Tarzan and His Mate (later cut), in which Tarzan tugs on Jane’s garment as they dive into the water and when she surfaces part of her breast is exposed. “It started such a furore,” recalled O’Sullivan, “with thousands of women objecting to my costume.”

In subsequent films Jane’s costume was more substantial while Tarzan’s loin-cloth was lengthened. Tarzan Escapes was started in 1934, but was over two years in the making, mainly because its first cut was too frightening and violent (including a vampire bat sequence). One of the directors brought in to re-shoot the material was John Farrow, who fell in love with O’Sullivan. The couple had to wait for two years for a papal dispensation because of a previous divorce of Farrow’s, but their subsequent marriage lasted 27 years (until the director’s death in 1963) despite his heavy drinking and infidelities. The couple had seven children – three sons and four daughters, the eldest girl Maria growing up to become the actress Mia Farrow. Between the Tarzan films, MGM cast O’Sullivan as ingenue in over 40 films – leading roles in B pictures but usually supporting roles in major ones.

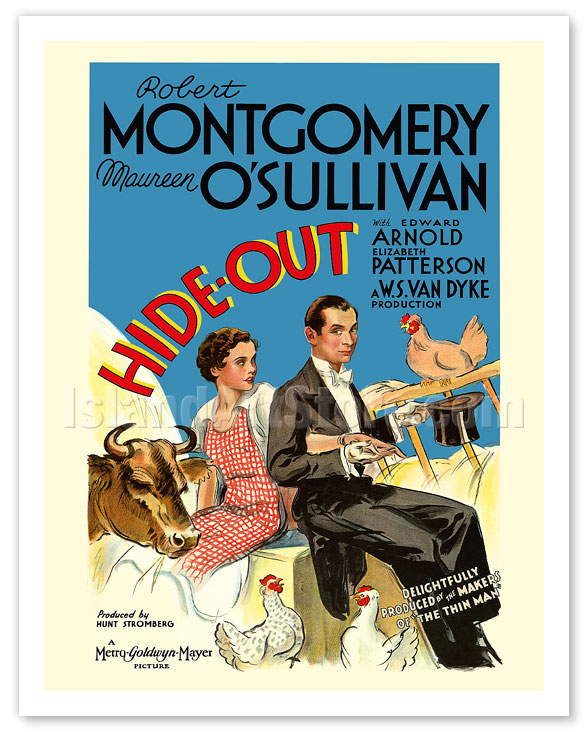

She was the distraught daughter who asks investigator Nick Charles to locate her missing father in The Thin Man (1934), the first of the series and the start of a lifelong friendship between the actress and Myrna Loy (“I loved Maureen’s warm exuberance,” wrote Myrna Loy later). In The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934), she was Henrietta, the romantically rebellious younger sister of Elizabeth Barrett, and in George Cukor’s classic film of David Copperfield (1935) she was Dora, David’s silly and ill-fated wife.

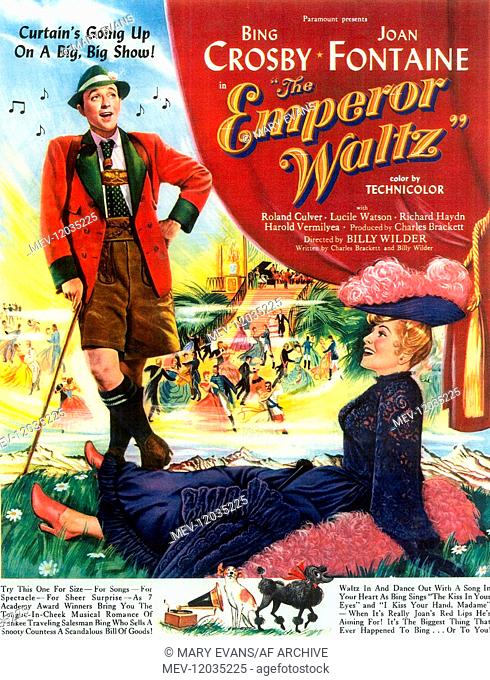

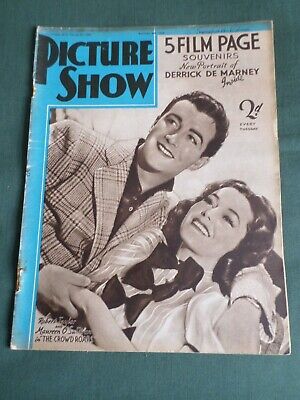

She was a flirtatious relative of Anna (Greta Garbo) in Anna Karenina (1935) and in Tod Browning’s bizarre Devil Doll (1936) she was the daughter of a wrongly convicted banker who gets his revenge by reducing his enemies to the size of dolls. With Allan Jones, she provided the romantic element in A Day at the Races (1937, starring the Marx Brothers) – O’Sullivan played the owner of the sanatorium over which Dr Quackenbush (Groucho) is put in charge – and she came to England in 1938 to film A Yank at Oxford in which she vied with Vivien Leigh for Robert Taylor. (Leigh had been O’Sullivan’s best friend at Roehampton when they were girls). One of the film’s uncredited writers was F. Scott Fitzgerald, who reputedly developed a romantic admiration for the actress and built up her part.

O’Sullivan was unhappy, though, that she was primarily identified with the role of Jane, and asked the studio to release her from the Tarzan series. A script was written in which the couple would have a son (adopted to placate the censors), and Jane would be killed by a hostile tribe, but when word leaked out, public protest proved so great that the studio re-shot the ending of Tarzan Finds a Son (1939) and gave O’Sullivan a raise in salary.

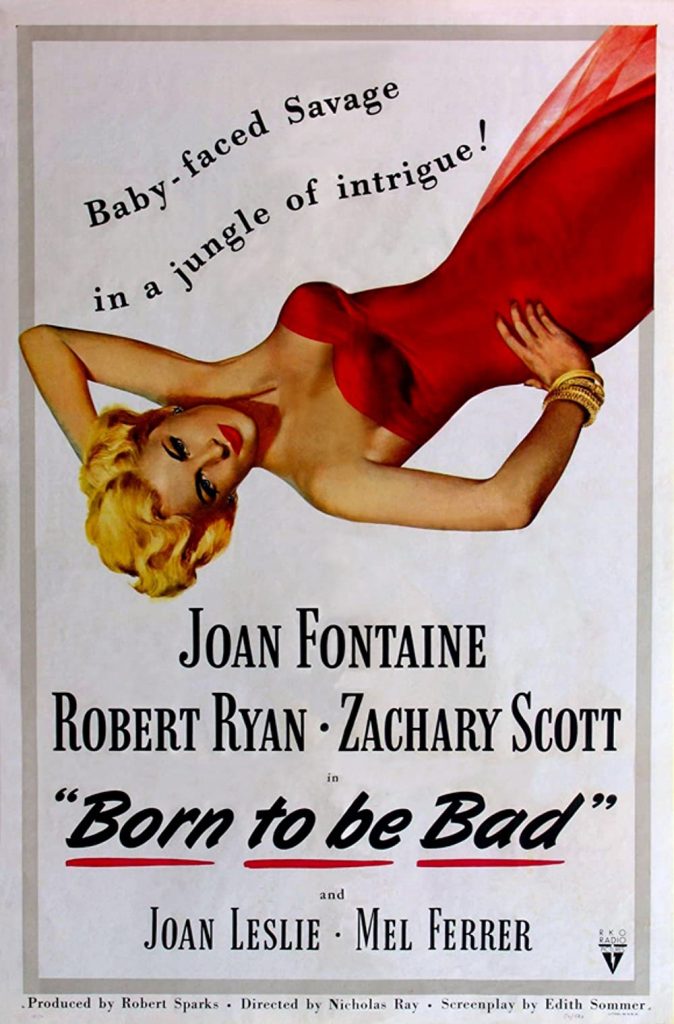

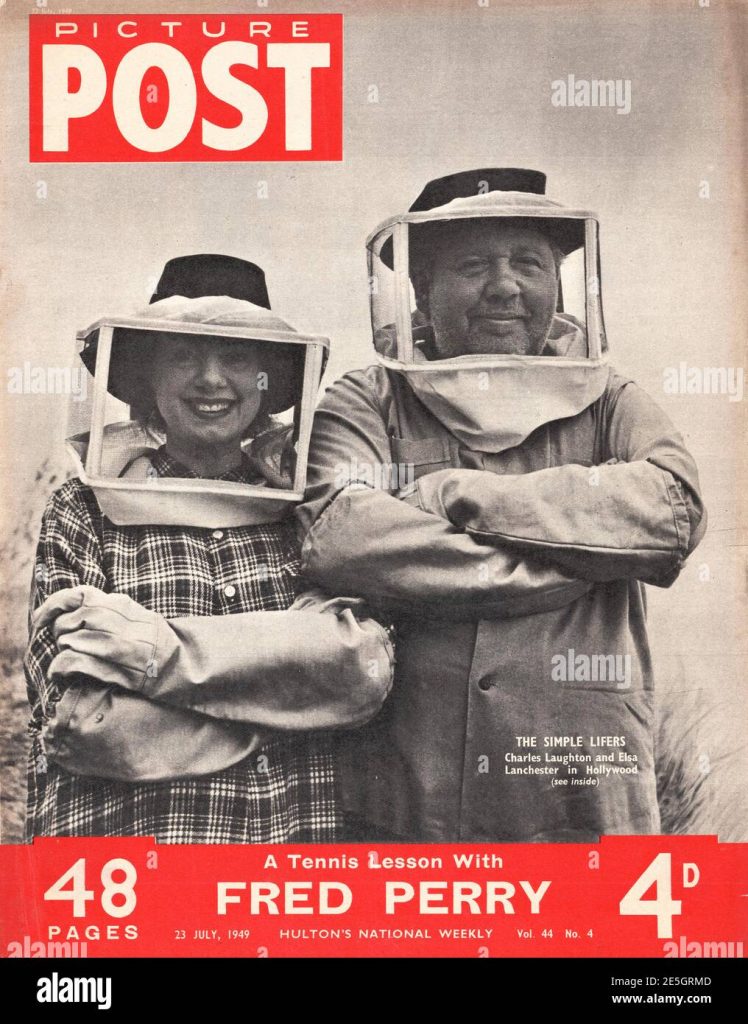

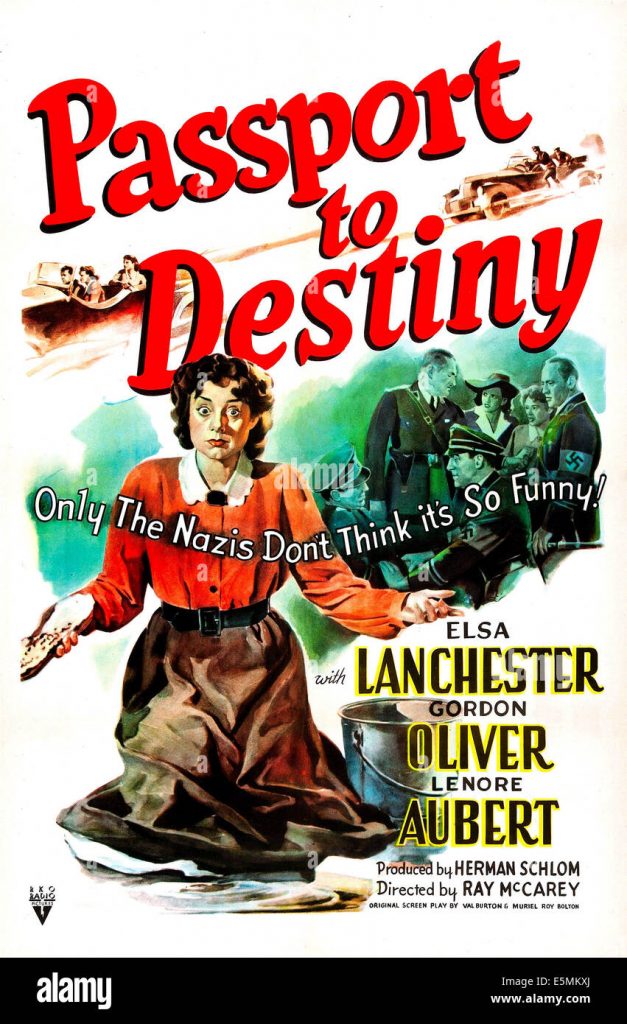

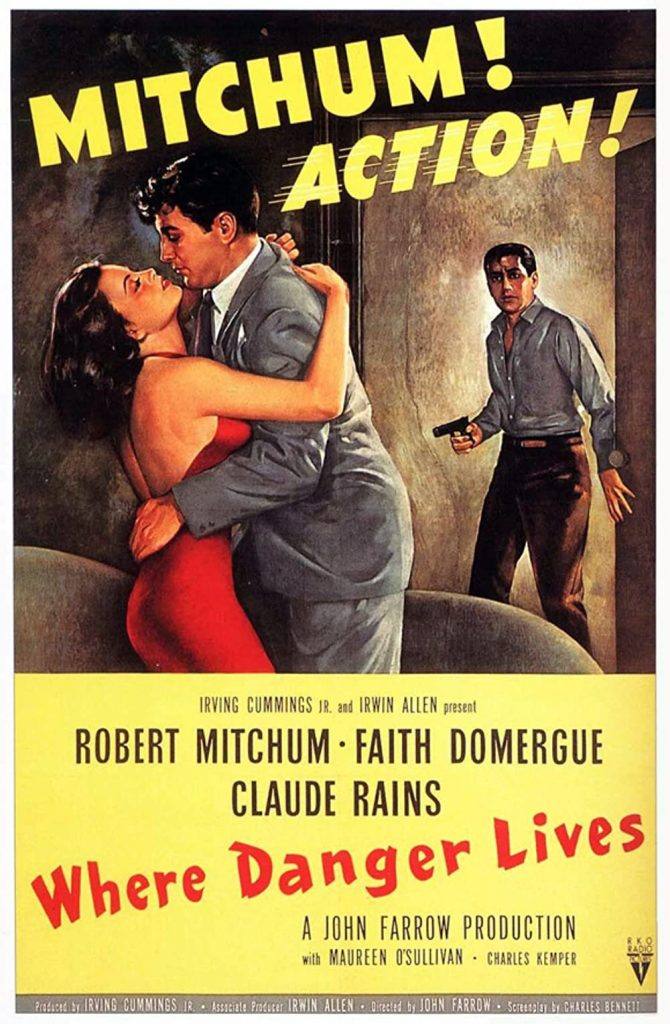

She was given the role of Jane Bennett in Pride and Prejudice (1940) but this was her last major MGM film, and when her contract expired after Tarzan’s New York Adventure (1942), O’Sullivan settled down to raise her large family. She returned to films in 1948 in her husband’s fine film noir The Big Clock, playing the wife of a magazine editor (Ray Milland), and followed this with another of Farrow’s films Where Danger Lives (1950) as a girlfriend of the doctor (Robert Mitchum).

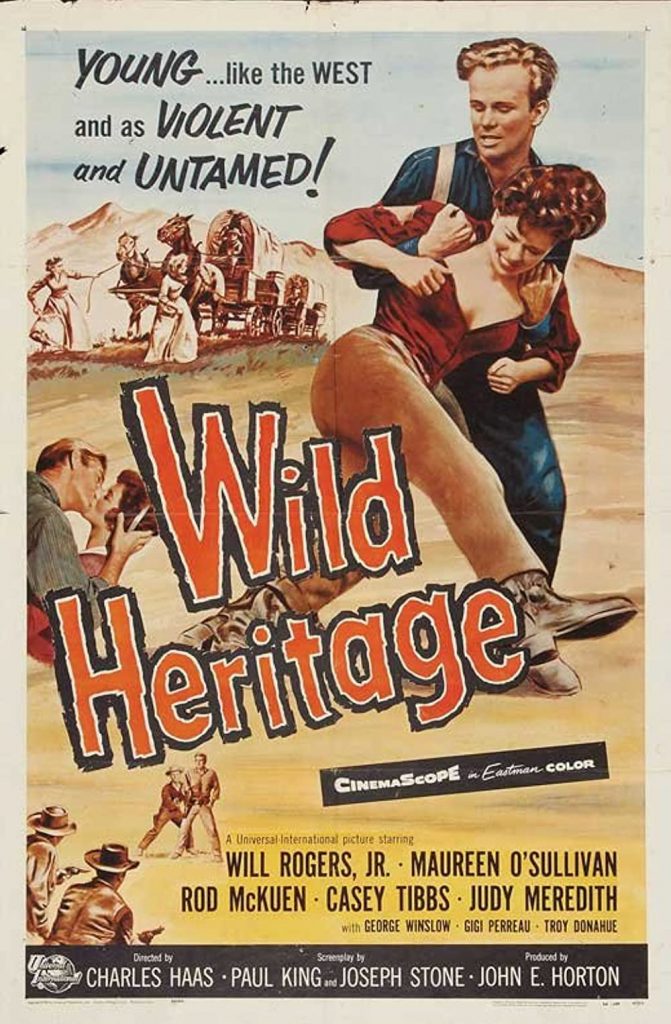

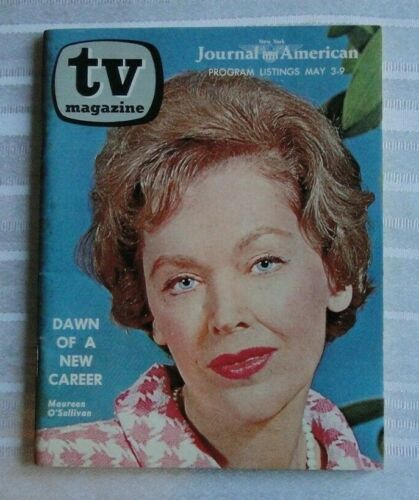

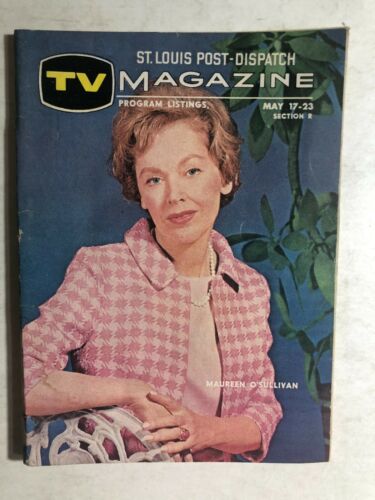

In the mid-1950s she hosted a television show, Irish Heritage, but spent most of her time nursing Mia through a bout of polio. In 1958 her son Michael was killed in an aeroplane crash while taking flying lessons and in 1963 her husband died.

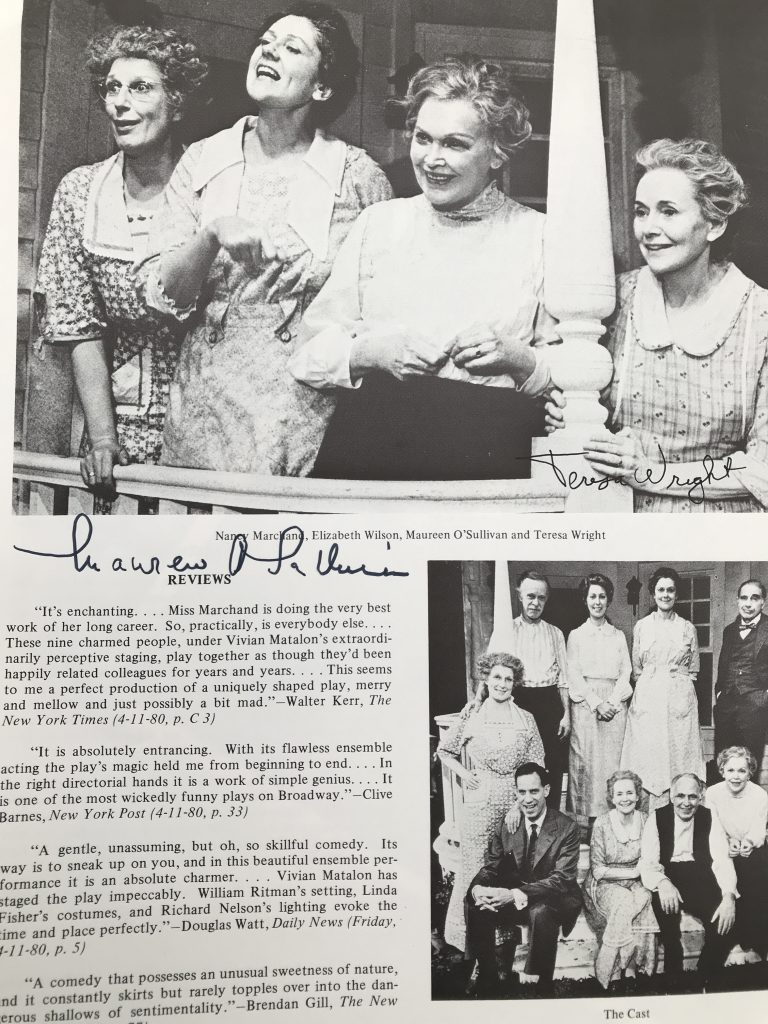

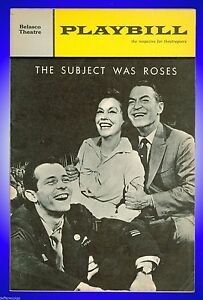

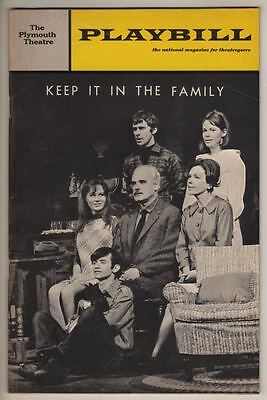

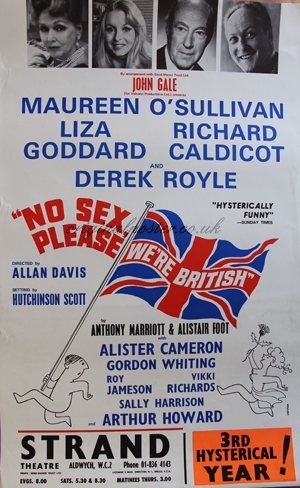

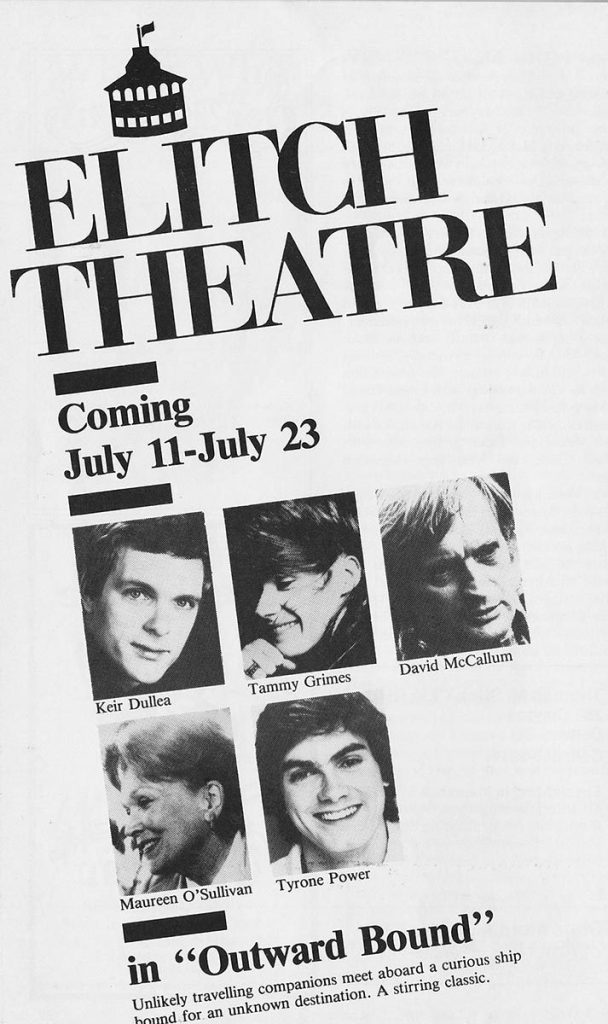

O’Sullivan had by then begun an active career in the theatre and in 1962 had opened in a hit comedy Never Too Late, receiving the best notices of her career as a middle-aged wife who becomes pregnant. Wrote Variety: “She looks great and handles light comedy with a warm, gracious flair.” She starred with the same leading man, Paul Ford, in the screen version (1965). She also starred in the Broadway version of the British comedy No Sex Please, We’re British (1973), gave an excellent performance in an all-star revival of Paul Osborn’s Morning At Seven (1983), and continued until a few years ago to be active in television.

O’Sullivan often professed a desire to remarry: “Children don’t take the place of a husband,” she said. “Many women – and I am one of them – need both.” In the late 1960s she fell in love with the actor Robert Ryan and it was thought that they would wed, but he then became ill and died in 1973, with O’Sullivan at his bedside. In 1983 she finally married again, to James E. Cushing, a building contractor.

A liberal, outspoken woman – when her two sons were arrested for possession of marijuana she commented that if youths want to indulge in activities it is their decision – she played mother to Mia in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), but Allen fired her from his film September (1987) and five years later, when his romance with her daughter broke up, she denounced him as a “desperate and evil man”. Over the years she came to appreciate the eternal appeal of the Tarzan films and their place in cinema history. “It’s nice to be immortal,” she stated, “and film has given us immortality.”

Maureen Paul O’Sullivan, actress: born Boyle, Co Roscommon, Ireland 17 May 1911; married 1936 John Farrow (died 1963; two sons, four daughters, and one son deceased) 1983 James E. Cushing; died Phoenix, Arizona 22 June 1998.

This obituary can also be accessed on-line here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography

Contributed by

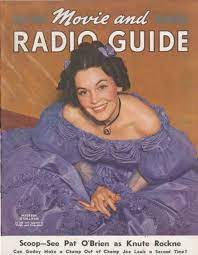

O’Sullivan, Maureen Paula (1911–98), actress, was born 17 May 1911 at Boyle, Co. Roscommon, one of the five children of Major Charles Joseph O’Sullivan of the Connaught Rangers, and his wife, Mary Lovatt (née Fraser). Educated briefly at a convent in Dublin, she also attended the Convent of the Sacred Heart at Roehampton in London. She completed her education at a convent in Boxmoor and at a finishing school in Paris.

Strikingly attractive, O’Sullivan was discovered in 1929 at the Dublin horse show ball by an American director, Frank Borzage, who was in Dublin casting actors for the film Song o’ my heart(1930), a musical starring John McCormack (qv). Signed by Twentieth Century Fox, she had minor roles in four more films before being dismissed by the studio in 1930. Following some films for independent studios, she signed for MGM in October 1931, embarking on her most famous role, of Jane to Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan in Tarzan the ape man (1932). Her second appearance as Jane, in Tarzan and his mate (1934), provoked an outcry from the Catholic Legion of Decency. Her provocative costumes were subsequently altered for later films such as Tarzan escapes (1936), Tarzan finds a son! (1939), and Tarzan’s secret treasure (1941). Throughout her career her supporting roles were generally superior to her more major parts, and she was critically acclaimed for her performances as Henrietta in The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934), Dora Splenlow in David Copperfield (1935), Kitty in Anna Karenina (1935), Judy Standish in A day at the races (1937), and Jane Bennett in Pride and prejudice(1940). During the war she appeared in war shorts and advertisements for the Canadian government and travelled to various American cities to promote British and Greek war relief. In 1941 she was honoured at the ninth naval district’s governor’s day. After her sixth Tarzan film, Tarzan’s New York adventure(1942), she retired from the cinema for four years, devoting her time instead to radio broadcasts and local charities.

O’Sullivan returned to the screen in 1948 in The big clock. In 1949 she formed an independent film company devoted to films of a family theme, and in the 1950s she began a career in television drama that lasted for forty years. She also wrote a series of short stories for children which were later broadcast on radio. Theatre roles predominated in the 1960s and 1970s, and were only briefly punctuated by a short and unsuccessful period as co-host of The today show in 1964. She made periodic returns to the cinema in the 1980s and was highly praised for her brief role in Woody Allen’s Hannah and her sisters (1986). Allen dismissed her from his film September in 1987 and courted her public displeasure five years later when he separated acrimoniously from her daughter Mia Farrow. Celebrated throughout her career by various catholic guilds, she was honoured at George Eastman House at the 1982 Festival of Artists. In 1983 she received an honorary doctorate from Sienna College and in 1988 she was honoured by a parade in her native Boyle. Altogether she appeared in over seventy feature films, and numerous television dramas.

She married on 12 September 1936 John Neville Villiers Farrow, an Australian film director and producer; she was his second wife. They had seven children, two of whom, Mia and Tisa, became actors. He died in January 1963, and she had an affair with the actor Robert Ryan in the late 1960s. On 22 August 1983 she married James E. Cushing, a building contractor. She died 22 June 1998 at Phoenix, Arizona.

Sources

John J. Concannon and F. E. Cull (ed.), The Irish-American who’s who (1984), 655; Irish-American Magazine (Feb. 1989), 32–8; Connie J. Billips, Maureen O’Sullivan, a bio-bibliography (1990); Ir. Times, 24 June 1998; Daily Telegraph, 25 June 1998; The Independent, 25 June 1998; Times, 25 June 1998; Michael Glazier (ed.), The encyclopaedia of the Irish in America (1999), 757