Phyllis Kirk obituary in “The Independent”.

The actress Phyllis Kirk will always be associated with her role as the dark-haired heroine in the 3-D horror movie House of Wax (1953), pursued through the night streets by a mad sculptor, played by Vincent Price, and saved by a whisker from being dipped in hot wax. Ironically, it was a role she fought against playing. “I tried to turn it down, with the arrogance of a young actress who thinks she is going to rule the world – and doesn’t realise, while she’s bitching about House of Wax, that that will probably be the most memorable thing she does in the movie business!”

Although Kirk was in some other fine films, notably the nostalgic musical Two Weeks with Love (1950) and the distinguished film noir Crime Wave (1954), and she had a prolific career in television, for which she starred in the series The Thin Man, it is for House of Wax that she will be primarily remembered, along with her campaigning for civil rights .

Of Danish descent, she was born Phyllis Kirkegaard in 1929 in Syracuse, New York. After working as a waitress, shop assistant and model, she moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey, in her late teens to be able to study acting in New York City with the famed coach Sanford Meisner. She made her Broadway début, having shortened her last name to Kirk, in 1949 in a play that promised much.

My Name is Aquilon was a comedy by the French actor Jean-Pierre Aumont, which had been a hit in Paris. Adapted for the United States by Philip Barry, it co-starred Lilli Palmer with Aumont, who played a charming cad whose conquests included Kirk, as a French maid. Before it opened to hostile reviews, Aumont had acrimonious battles with Barry over the adaptation, and when Palmer was hailed as the best thing about the evening, Aumont stated that on opening night she had given an entirely different performance to the one they had been rehearsing for six weeks. The play ran for 31 performances, but Kirk’s performance was noted by a talent scout for Sam Goldwyn, and after her dispiriting introduction to Broadway, Kirk was glad to accept an offer to go to Hollywood.

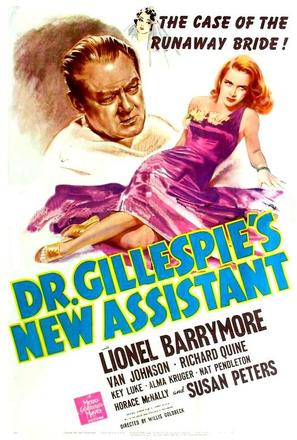

She made her screen début in the Goldwyn drama Our Very Own (1950), playing the friend of a teenager (Ann Blyth, the film’s star) who is traumatised by the discovery that she is adopted. Although Blyth could do little with the main role (her exasperating character needed a good shaking), Kirk was very sympathetic as a girl who envies Blyth the love and support with which she has been raised (Kirk’s father is unable to find the time to attend her graduation). Goldwyn then sold Kirk’s contract to MGM, who gave her a less sympathetic role in the delightful musical Two Weeks With Love, as the haughty beauty at summer camp who patronises her younger friend (Jane Powell) and jealously tries to sabotage a budding romance between Powell and Latin lover Ricardo Montalban.

In 1952 Kirk moved to Warners, where, after small roles in About Face, The Iron Mistress and Stop, You’re Killing Me (all 1952), she was given the leading female role in House of Wax, playing the character created by Fay Wray in an earlier version of the tale, Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). “I was not interested in becoming the Fay Wray of my time,” Kirk told the historian Tom Weaver,

and I was told, “You’re under contract, and you’ll do what we ask you to do, unless you care to be suspended.” I also did not want to be in a film that was using a gimmick, which I thought 3-D was. I went on to have a lot of fun. Vincent Price was a divine man, and a divine actor, and director André de Toth was a remarkable, highly intelligent guy who was more appreciated in Europe than at home.

Kirk worked with de Toth in her next two films, a western co-starring Randolph Scott, Thunder Over the Plains (1953), and an exceptional film noir, Crime Wave, in which she was the wife of a former convict (Gene Nelson) who is hounded by a dogged, toothpick-chewing police detective (Sterling Hayden). The French director Bertrand Tavernier said that,

de Toth showed himself to be particularly inspired by the delightful Phyllis Kirk, a modest and under-rated actress whom he rewarded for

rescuing many inadequately written characters (as in Thunder Over the Plains) by giving her at last a role worthy of her in Crime Wave, where she is splendidly dignified and straightforward.

(Another French director, Jean-Pierre Melville, acknowledged that he loved Crime Wave enough to steal its ending for his own film noir Le Deuxième Souffle, 1966.) Among Crime Wave’s splendid supporting cast playing lowlifes who hold Kirk hostage was Charles Buchinsky (later Bronson), who had also menaced her in House of Wax. “Now there was a piece of work,” said Kirk.

I didn’t particularly like him, he was full of oats and swaggering around and being terribly macho – it may have to do with the fact that he wasn’t very tall. I got to know him better over the years, and began to like him much more as an actor.

Kirk then became one of those American stars used to boost British product, starring opposite John Bentley in River Beat (1954), a superior “B” movie and an impressive directorial début by Guy Green, who stated, “Phyllis Kirk was an up-and-coming actress who never became a major star, but she was a very bright, nice girl, whom I was lucky to have.” Kirk recalled,

My favourite story in London was to point out that the director of House of Wax had only one eye and couldn’t see in three dimensions. Everybody in London thought that was hilarious, but I’m sure nobody at Warner Brothers thought it hilarious that I was saying that.

Kirk was leading lady to Frank Sinatra in the western Johnny Concho (1956) and to Jerry Lewis in The Sad Sack (1957), but she was increasingly acting on television, with guest appearances on anthology drama shows such as Studio One, Schlitz Playhouse of the Stars and The Ford Television Theatre. “I wouldn’t trade my Hollywood experience for anything,” she said,

but TV taught me the most about acting. There were a couple of live television things that I loved doing. There was a series called Robert Montgomery Presents, and we did The Great Gatsby [1955] with Montgomery as Gatsby and I played Daisy Buchanan. I loved that, and I thought they did a wonderful job with it.

Kirk’s most famous role on television was her portrayal of Nora Charles in The Thin Man, a series that ran for three years (1957-59). Peter Lawford played her playboy-detective husband Nick in the show, based on the Dashiell Hammett novel and the MGM film series. Her last television role was in a 1970 episode of The FBI.

Long considered a confirmed bachelor-girl, the strong-willed and independent Kirk had a long friendship with the mordant comic Mort Sahl, but later married the television producer Warren Bush, who died in 1992.

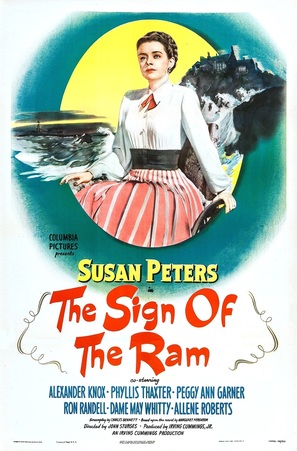

As a child, Kirk had battled with polio, and in the early Seventies, after a fall damaged her hip, she had trouble walking. During her film career, she had contributed interviews and articles to the newspaper of the American Civil Liberties Union, and as her acting career slowed, she devoted more time to political and social causes, gaining particular notoriety when she joined other celebrities, including Ray Bradbury and Norman Mailer, in campaigning against the death sentence of the convicted murderer Caryl Chessman. “I even visited Chessman several times in San Quentin until his execution in 1960,” Kirk said. “There’s no doubt he did some ghastly things, but he did not kill anybody. Also, I abhor capital punishment, always have and always will.”

Before her retirement in 1992, Kirk also worked in public relations and as a publicist for CBS News.

Tom Vallance

“The Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.