IMDB entry:

The entrancing and exotic-eyed “B”-level leading lady Jody Lawrance, whose 1950’s career was spotty at best, provided lovely diversion from the manly adventure movies she helped bring to the screen. Personal turmoil and studio conflicts, however, ultimately hurt her career and the remainder of her life was spent out of the limelight.

She was born Nona Josephine Goddard in Fort Worth, Texas, on October 19, 1930. Her childhood was troubled and disruptive. Parents Ervin S. (“Doc”) and Eleanor (née Roeck) Goddard divorced while Jody was a child. Ervin, nicknamed “Doc” although he was not one, was an amateur inventor and research engineer at the Adel Precision Products Company at one point. Moving to Caliornia, he eventually married Grace McGee in 1937. Jody subsequently migrated to California and lived with her father and stepmother in their Van Nuys bungalow. Marilyn Monroe (then Norma Jeane Baker) was a foster child of her stepmother Grace, who knew Norma Jeane’s mother when both worked for Columbia — Grace as a film librarian and and Gladys as a film cutter. Jody and Norma Jeane lived together briefly in 1941-1942.

Jody went on to attend Beverly Hills High School (studying under Benno Schneider and his wife) and the Hollywood Professional School. Excelling as a swimmer, Jody’s first shot was appearing in a water show operated by Larry Crosby, who was also a publicity manager for famous younger brother Bing Crosby.

The teenager was awarded her first on-camera professional part on the TV show “The Silver Theatre” in 1949. Because her real name, Nona Goddard, lacked glamor, she changed it to Jody (short for Josephine, her middle name) Lawrance (her maternal grandmother’s maiden name). Jody’s drama teacher Schneider managed to get her an introduction to Columbia. The studio took an immediate interest in the 19-year-old beauty and signed her to a 7-year contract at $250 per week.

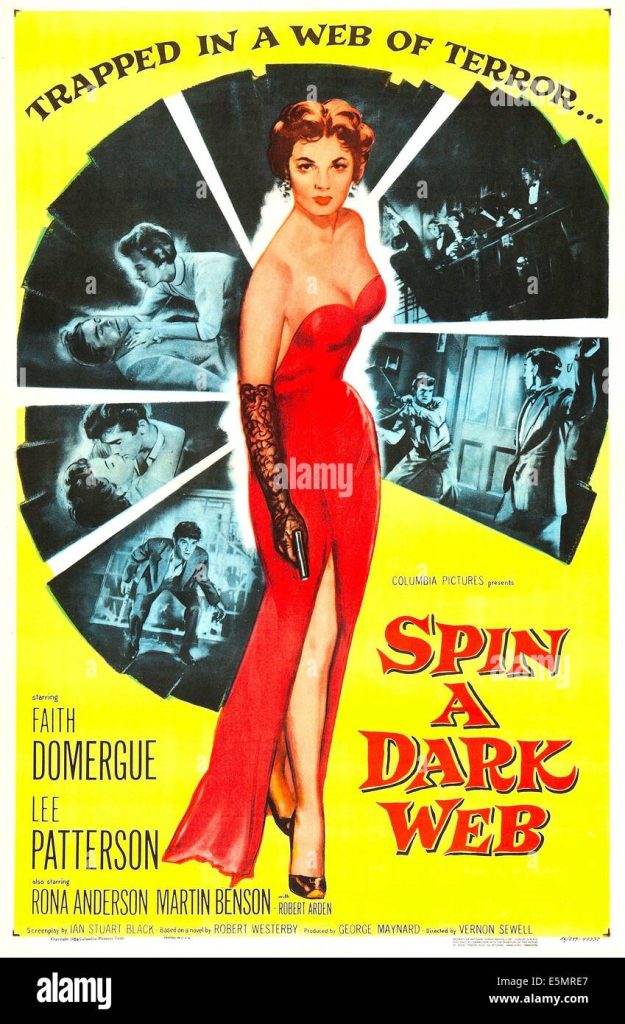

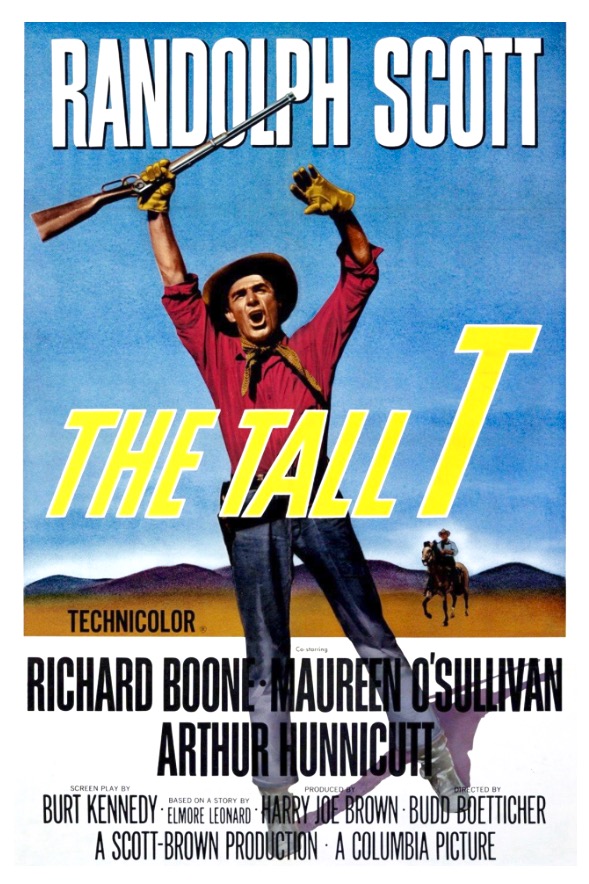

Jody made four relatively strong films in 1951. She provided damsel-in-distress duty in her screen debut between up-and-coming screen hero John Derek and established villainAnthony Quinn in the spirited swashbuckler Mask of the Avenger (1951). This was followed by The Family Secret (1951) playing the altruistic fiancée to a murder suspect (again, John Derek. Things looked even more promising when she co-starred an exotic love interest to robust Burt Lancaster in the Eastern adventure yarn Ten Tall Men (1951). Her final film that year was a horror opus portraying the fiancée to Louis Hayward as theThe Son of Dr. Jekyll (1951).

She started the following year off with the adventure film The Brigand (1952) opposite handsome, sliver-eyed Anthony Dexter, better known for his captivating Valentino-like looks than for his acting ability. In 1953 career problems surfaced when the studio assigned Jody, who had now completed six film projects, to a lackluster role in one of its minor musicals, a poor man’s version of “On the Town” entitled All Ashore (1953) which starred sailors-on-leave Mickey Rooney, Dick Haymes and Ray McDonald. Peggy Ryan,Barbara Bates and Jody were cast as their the love interests. Set this time on California’s Catalina Island instead of New York, Jody balked at the assignment while citing a lack of confidence in her singing and dancing abilities. She ask the studio to replace her but Columbia refused and the actress begrudgingly filmed the movie. Her “difficulty” with the studio on this assignment ultimately led to a break of her contract. Feeling overlooked by the studio at the time, she supposedly did not regret her release too much.

On her own, however, the quality of Jody’s films declined markedly with her the “Poverty Row” independent film, the subpar and highly distorted biographical piece Captain John Smith and Pocahontas (1953) again starring Anthony Dexter. It was revealed that Jody suffered a frightening allergic reaction on the set after dying her lighter hair jet black for the role. Among many other problems, the 23-year old, blue-eyed actress was quite miscast in the role of the much younger Indian maiden. The released film was a dismal failure and Jody’s career suffered as a result.

Finding almost no offers in 1954-1955 and in order to make ends meet, Jody took on employment as an ice cream shop waitress near the UCLA campus in Los Angeles. The story goes that one day one of her customers was her former co-star Burt Lancaster. He came to her aid by introducing her to his friend, director Michael Curtiz, who reignited her career with his minor film noir The Scarlet Hour (1956) which starred Tom Tryon and had Jody playing a second femme role behind Carol Ohmart, who was being built up as Paramount’s supposed answer to a difficult Marilyn Monroe at the time. Jody was promoted as one of the “Deb Stars of 1955” along with other hopefuls including Cathy Crosby, Anita Ekberg, Mara Corday, Marisa Pavan and Lori Nelson, among other lesser knowns.

Back on the boards again, Jody revived her look on screen as a blonde again. Things looked hopeful when Paramount Studios signed her to a contract, earning $300 a week. In the spiritual drama The Leather Saint (1956), she plays a platinum-blonde nightclub singer (and even sings a bit of “I’m in the Mood for Love” in the film) and temptress to (once again) John Derek whose Episcople minister agonizes over his decision to box for money in order help medically finance church/community projects for special needs children.

Things fell apart once more, however, when Paramount released her the following year. It seems that the studio was perturbed when, while promoting her to the public as a sexy single, Jody resisted the cheesecake angle and also secretly married Bruce Tilton (1930-2007), an airplane parts company executive, in Las Vegas on April 7, 1956. A daughter, Victoria, was born a year later.

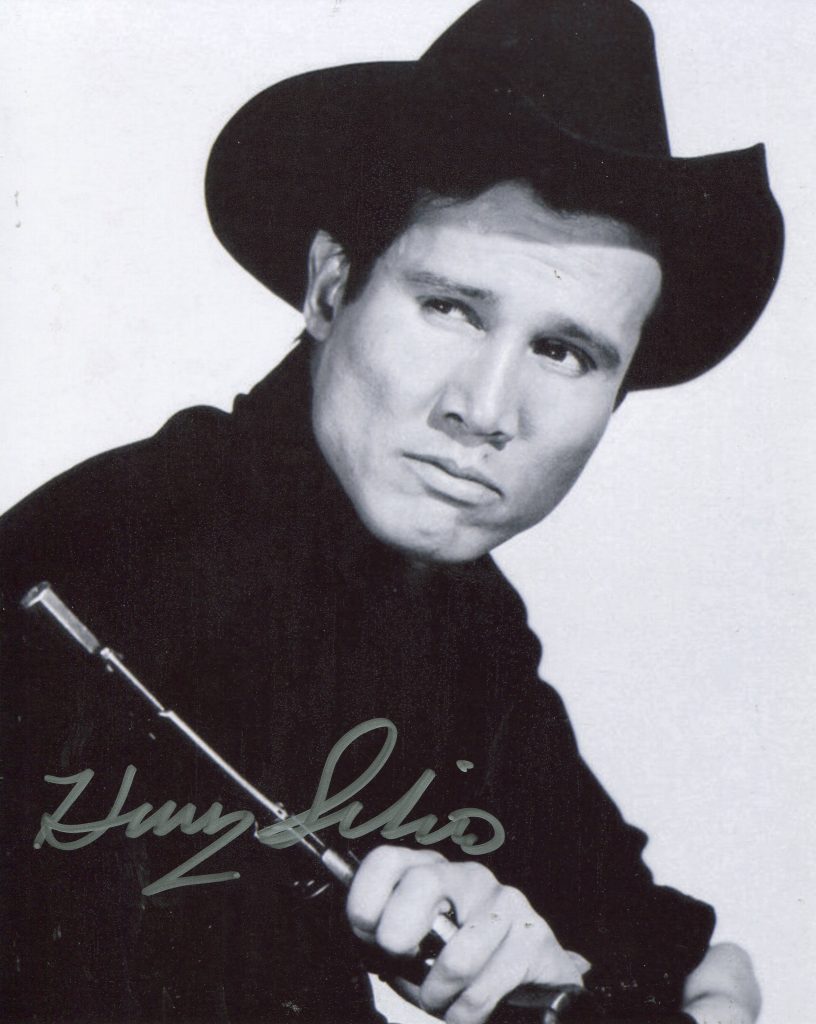

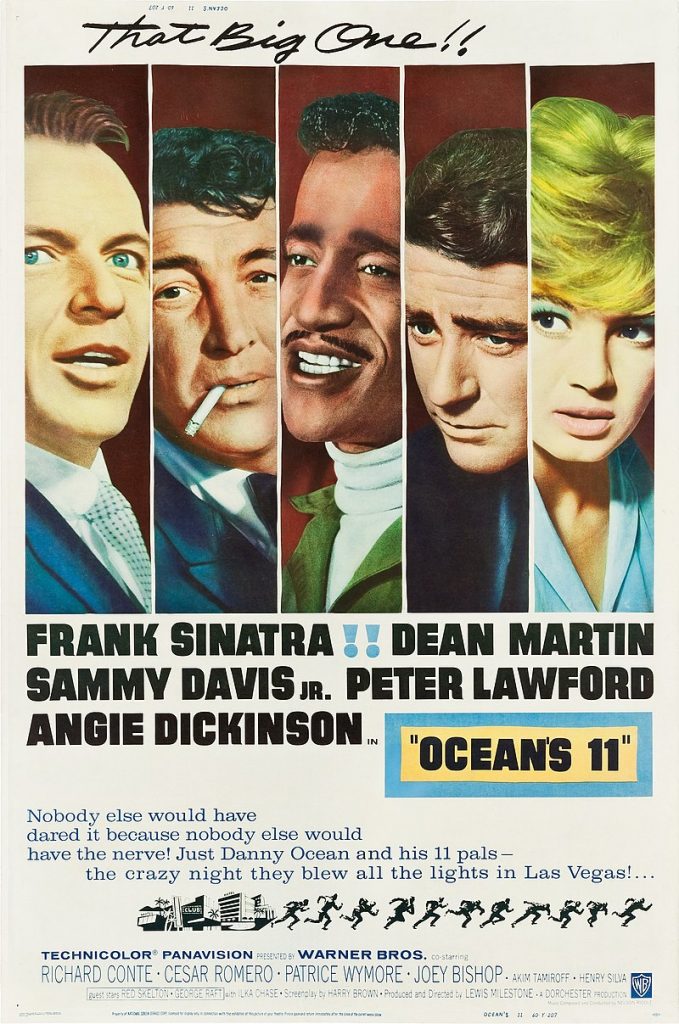

She remained unproductive career-wise during this period of new marriage and more family. By April of 1958, however, the Tilton marriage had dissolved and a bitter custody suit ensued (in the end, Jody lost). While she returned to the screen, the pickings were slim. She landed minor parts in the Shirley Booth vehicle Hot Spell (1958) and Barry Sullivan film The Purple Gang (1959), and found isolated work on TV in such dramatic fare as “Perry Mason,” “The Loretta Young Show” and “The Rebel”. Her last screen role of any substance was the minor western Stagecoach to Dancers’ Rock (1962) starringMartin Landau.

Jody met second husband Robert Wolf Herre and they married in November of 1962. Two children, Robert Jr. and Abigail (“Chrissy”) were born from this relationship. Other than an isolated TV appearance on “The Red Skelton Show” in 1968, little was heard of Jody following this period until it was learned that she had died in Ojai, California on July 10, 1986, at age 55.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.