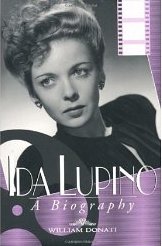

She was born into a family of Italian origin which had entertained the British for generations in circuses and variety theatres. Her father was Stanley Lupino, star of film and stage musicals. Ida was only 15 when she made her first film, Her First Affaire (1933), cast as a teenage vamp, so there was some surprise when Paramount signed her to play Alice in Alice in Wonderland. Once in Hollywood, Paramount changed its collective mind about her, and for the next four years she was shuttled between roles of her own age, ingenues and glamourpants parts for which she was much too young.

In 1938 she married the actor Louis Hayward. Hayward had also been getting nowhere fast in Hollywood, but at this time the producer Edward Small decided that he had star potential, which in turn made Lupino more aggressive towards her own career. She convinced the director William A. Wellman that only she could play the cockney whore who inspires Helder (Ronald Colman) in The Light That Failed (1939), based on Kipling’s first novel.

Her emotive handling of a difficult role convinced Warner Bros that they had found someone to fill Bette Davis’s old shoes, for they were planning a partial remake of Bordertown called They Drive By Night (1940). It was a showy role, lasciviously pursuing trucker George Raft while showing only contempt for her fond, much older husband, Alan Hale, who is (of course) his boss and best friend; furthermore, it required her to go spectacularly mad on the witness stand at the climax. Jack Warner was so impressed by the first few days’ rushes that he signed Lupino to a seven-year contract, whereupon she stayed off work on the advice of her astrologer. Warner devotes almost a chapter to this in his memoirs, but he seems to have persuaded himself that this was how real stars behave, for he gave her billing over Bogart in her next film, Walsh’s High Sierra (1941), despite the fact that she has the lesser role (as Bogart’s moll).

Warner had had trouble with Davis, whose temperament (in the cause of better material) was equalled only by her talent and her popularity. Lupino accordingly had value to Warner beyond the unexpected maturing of her abilities: she was a “threat” to Davis, at worst replacing her as his leading female star – or appearing in the many properties purchased for Davis in the first place.

Lupino held her own against such heavyweights as Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield in the best screen version of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf (also 1941) despite this interpolation – an ex-con picked up at sea to inflame the all-male crew. She staked her claim to be the first of the decade’s many wicked ladies at Columbia, in Ladies in Retirement (1941), as the housekeeper who conspires with her “nephew”, Hayward, to murder the blowsy ex-actress who is her boss.

She was a “Lady Macbeth of the slums” (Picturegoer) in The Hard Way (1943), stopping only at murder to ensure her daughter’s stardom – with Joan Leslie in the role. The New York critics voted Lupino’s performance the year’s best, setting the seal on her stardom.

In Devotion (1945), she was Emily Bronte, Olivia de Havilland was Charlotte and Nancy Coleman Anne, with the Italian-born Viennese-accented Paul Henried as the Irish Mr Nicholls. The critic Richard Winnington found the film “painless. It never got nearer to the subject than the names and consequently didn’t hurt.”

Lupino – and audiences – were better served by Walsh’s noir-ish The Man I Love (1946), in which she proved how effortlessly she inhabited those tough, world-weary dames, in this case a night-club singer, preparing herself for damnation to prevent her sister from throwing herself at the heel who runs the joint, Robert Alda. Even more splendid is the not dissimilar Road House (1948), with Lupino greedily suggesting the small-time ambition and essential seediness of a B-girl who has spent too many nights in an atmosphere of stale cigarette smoke and beer-guzzling – and she got to croon the torch song for which this film was famous, “Again (it mustn’t happen again)”. “She does more without a voice than anyone I’ve ever heard,” says the cashier, Celeste Holm.

It was directed at 20th Century-Fox by Jean Negulesco, invited there by Zanuck after his work with Lupino in Deep Valley (1947) which featured one of her first wholly admirable or pitiable heroines, a timid farmgirl whose life is changed by an encounter with a convict, Dane Clark. There were more to come (at various studios): a frightened bride in A Woman in Hiding (1950) – frightened of Stephen McNally, though the cast included Howard Duff, whom Lupino later married.

A little later she turned to directing – the only female director of consequence between Dorothy Arzner and Joan Micklin Silver – and chiefly for the Filmakers, a company she had founded with her then husband, Collier Young. As early as 1949 she had turned to television, writing and producing, before carrying out these same chores on a low-budget movie concerning the problems of an unwed mother, Not Wanted (1949), and she took over the direction when Elmer Clifton became ill. With the determination which characterised her work before the cameras, she went on to handle other subjects in the same serious low-key vein, including The Hitch-Hiker (1952), about a paranoid killer (William Talman) who forces two businessmen (Edmond O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy) to travel with him at gunpoint. This is regarded as her best film as a director. They managed to get a higher budget for another sympathetic study of a social problem, The Bigamist (1953). He was Edmond O’Brien, with Lupino and Joan Fontaine as his two wives – with a screenplay by Young, now divorced from the first lady and married to the second.

Lupino continued to act and direct in television until the Seventies, including a series with Duff, Mr Adams and Eve. In her later years she found time for a new hobby, motor-cycling.

David Shipman

Ida Lupino, actress, producer, director and writer: born London 4 February 1918; married 1938 Louis Hayward (marriage dissolved 1945), 1948 Collier Young (marriage dissolved 1951), 1951 Howard Duff (one daughter; marriage dissolved 1972): died Burbank, California 3 August 1995.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

She was stubborn, sullen, tiny (5ft 3in) and resilient. With a mink thrust over her shoulder-pads and an orchid in her hair, Ida Lupino made it clear – in a silky, querulous voice – that she resented living in a man’s world. Like Joan Crawford, she was glamorous in different ways at different times in her career: she too had a strong, mesmerising personality but with a wider range. She was the archetypal Hollywood star, always surging back after a setback.

She was born into a family of Italian origin which had entertained the British for generations in circuses and variety theatres. Her father was Stanley Lupino, star of film and stage musicals. Ida was only 15 when she made her first film, Her First Affaire (1933), cast as a teenage vamp, so there was some surprise when Paramount signed her to play Alice in Alice in Wonderland. Once in Hollywood, Paramount changed its collective mind about her, and for the next four years she was shuttled between roles of her own age, ingenues and glamourpants parts for which she was much too young.

In 1938 she married the actor Louis Hayward. Hayward had also been getting nowhere fast in Hollywood, but at this time the producer Edward Small decided that he had star potential, which in turn made Lupino more aggressive towards her own career. She convinced the director William A. Wellman that only she could play the cockney whore who inspires Helder (Ronald Colman) in The Light That Failed (1939), based on Kipling’s first novel.

Her emotive handling of a difficult role convinced Warner Bros that they had found someone to fill Bette Davis’s old shoes, for they were planning a partial remake of Bordertown called They Drive By Night (1940). It was a showy role, lasciviously pursuing trucker George Raft while showing only contempt for her fond, much older husband, Alan Hale, who is (of course) his boss and best friend; furthermore, it required her to go spectacularly mad on the witness stand at the climax. Jack Warner was so impressed by the first few days’ rushes that he signed Lupino to a seven-year contract, whereupon she stayed off work on the advice of her astrologer. Warner devotes almost a chapter to this in his memoirs, but he seems to have persuaded himself that this was how real stars behave, for he gave her billing over Bogart in her next film, Walsh’s High Sierra (1941), despite the fact that she has the lesser role (as Bogart’s moll).

Warner had had trouble with Davis, whose temperament (in the cause of better material) was equalled only by her talent and her popularity. Lupino accordingly had value to Warner beyond the unexpected maturing of her abilities: she was a “threat” to Davis, at worst replacing her as his leading female star – or appearing in the many properties purchased for Davis in the first place.

Lupino held her own against such heavyweights as Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield in the best screen version of Jack London’s The Sea Wolf (also 1941) despite this interpolation – an ex-con picked up at sea to inflame the all-male crew. She staked her claim to be the first of the decade’s many wicked ladies at Columbia, in Ladies in Retirement (1941), as the housekeeper who conspires with her “nephew”, Hayward, to murder the blowsy ex-actress who is her boss.

She was a “Lady Macbeth of the slums” (Picturegoer) in The Hard Way (1943), stopping only at murder to ensure her daughter’s stardom – with Joan Leslie in the role. The New York critics voted Lupino’s performance the year’s best, setting the seal on her stardom.

In Devotion (1945), she was Emily Bronte, Olivia de Havilland was Charlotte and Nancy Coleman Anne, with the Italian-born Viennese-accented Paul Henried as the Irish Mr Nicholls. The critic Richard Winnington found the film “painless. It never got nearer to the subject than the names and consequently didn’t hurt.”

Lupino – and audiences – were better served by Walsh’s noir-ish The Man I Love (1946), in which she proved how effortlessly she inhabited those tough, world-weary dames, in this case a night-club singer, preparing herself for damnation to prevent her sister from throwing herself at the heel who runs the joint, Robert Alda. Even more splendid is the not dissimilar Road House (1948), with Lupino greedily suggesting the small-time ambition and essential seediness of a B-girl who has spent too many nights in an atmosphere of stale cigarette smoke and beer-guzzling – and she got to croon the torch song for which this film was famous, “Again (it mustn’t happen again)”. “She does more without a voice than anyone I’ve ever heard,” says the cashier, Celeste Holm.

It was directed at 20th Century-Fox by Jean Negulesco, invited there by Zanuck after his work with Lupino in Deep Valley (1947) which featured one of her first wholly admirable or pitiable heroines, a timid farmgirl whose life is changed by an encounter with a convict, Dane Clark. There were more to come (at various studios): a frightened bride in A Woman in Hiding (1950) – frightened of Stephen McNally, though the cast included Howard Duff, whom Lupino later married.

A little later she turned to directing – the only female director of consequence between Dorothy Arzner and Joan Micklin Silver – and chiefly for the Filmakers, a company she had founded with her then husband, Collier Young. As early as 1949 she had turned to television, writing and producing, before carrying out these same chores on a low-budget movie concerning the problems of an unwed mother, Not Wanted (1949), and she took over the direction when Elmer Clifton became ill. With the determination which characterised her work before the cameras, she went on to handle other subjects in the same serious low-key vein, including The Hitch-Hiker (1952), about a paranoid killer (William Talman) who forces two businessmen (Edmond O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy) to travel with him at gunpoint. This is regarded as her best film as a director. They managed to get a higher budget for another sympathetic study of a social problem, The Bigamist (1953). He was Edmond O’Brien, with Lupino and Joan Fontaine as his two wives – with a screenplay by Young, now divorced from the first lady and married to the second.

Lupino continued to act and direct in television until the Seventies, including a series with Duff, Mr Adams and Eve. In her later years she found time for a new hobby, motor-cycling.

David Shipman

Ida Lupino, actress, producer, director and writer: born London 4 February 1918; married 1938 Louis Hayward (marriage dissolved 1945), 1948 Collier Young (marriage dissolved 1951), 1951 Howard Duff (one daughter; marriage dissolved 1972): died Burbank, California 3 August 1995.

The above “Indepednent” obituary can also be accessed here.