Hollywood Actors

TCM Overview:

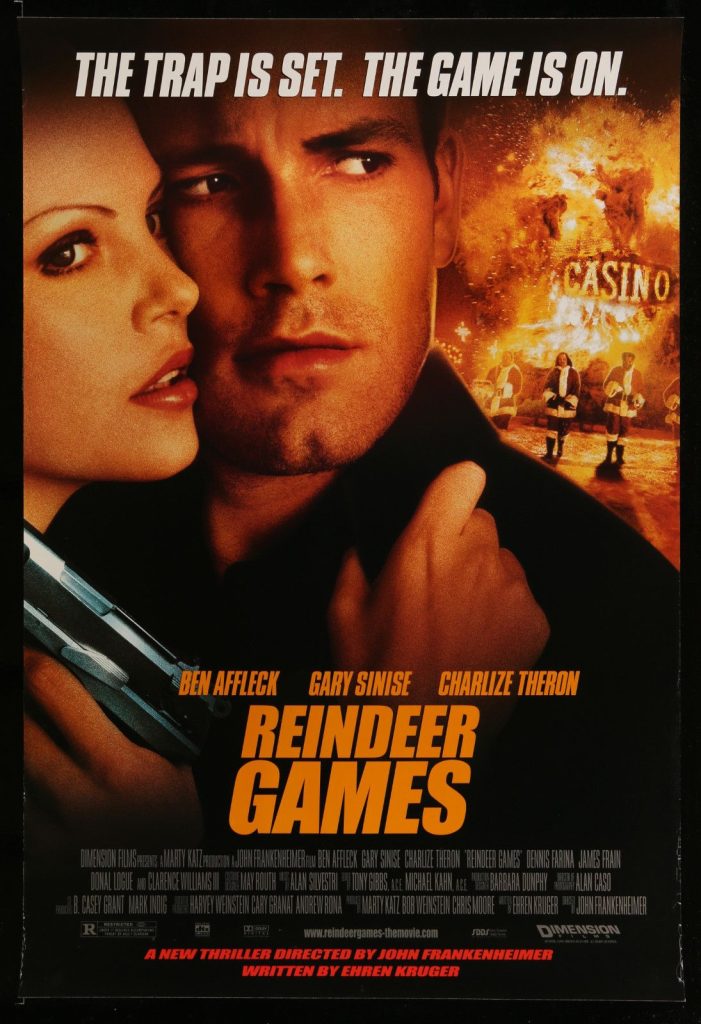

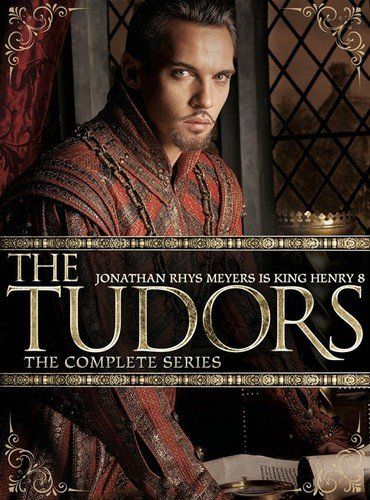

Actor James Frain was a quintessential chameleon. Regardless of the role he portrayed – whether it was a sinister Spaniard in “Elizabeth” (1998), a classical pianist in “Hilary and Jackie” (1998), or a soft-spoken librarian in “Where the Heart Is” (2000) – Frain always extracted hidden layers of his characters’ emotions and brought them to the forefront. Frain also delivered strong performances on the action drama “24” (Fox, 2001-2010) as well as on the critically acclaimed Showtime miniseries “The Tudors” (2007-2010), as a commoner who rises to power as King Henry VIII’s ally. But it was Frain’s impressive turn as a psychotic vampire obsessed with a human on the award-winning HBO series “True Blood” (2008- ) that put him on the map and successfully showcased his range as a performer.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

“Wikipedia” entry:

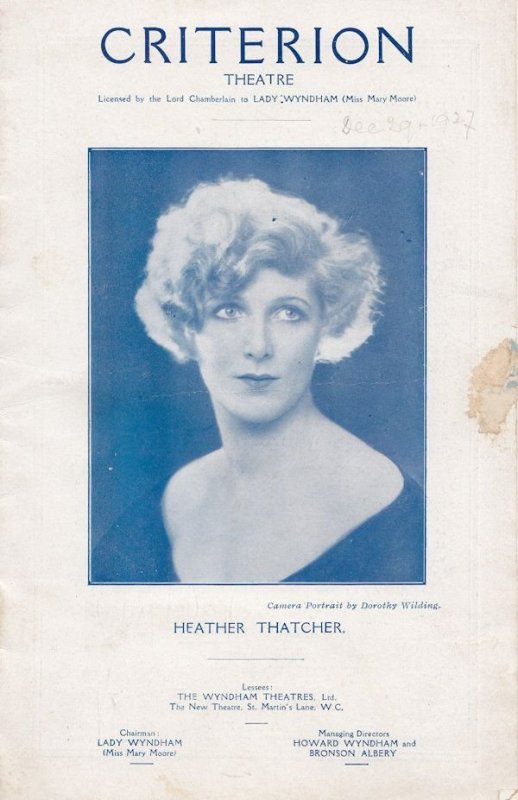

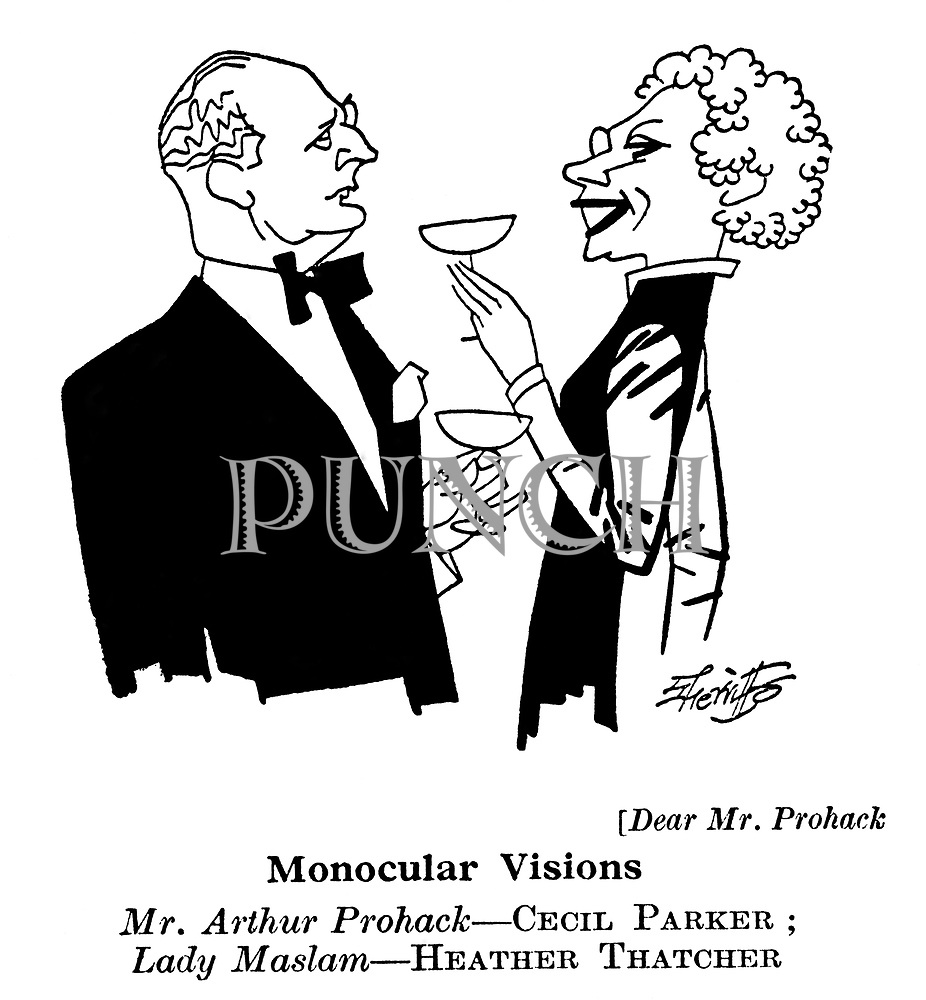

Heather Thatcher (3 September 1896 – 15 February 1987) was an English actress in theatre and films. She was from London.

By 1922 Thatcher was a dancer. She was especially noted for her interpretation of an Egyptian harem dance. Her exotic clothes were designed in Russia. They featured stencil slits in the waist, trouserettes and sleeves. Her attire was billed as the boldest costume ever shown in England.

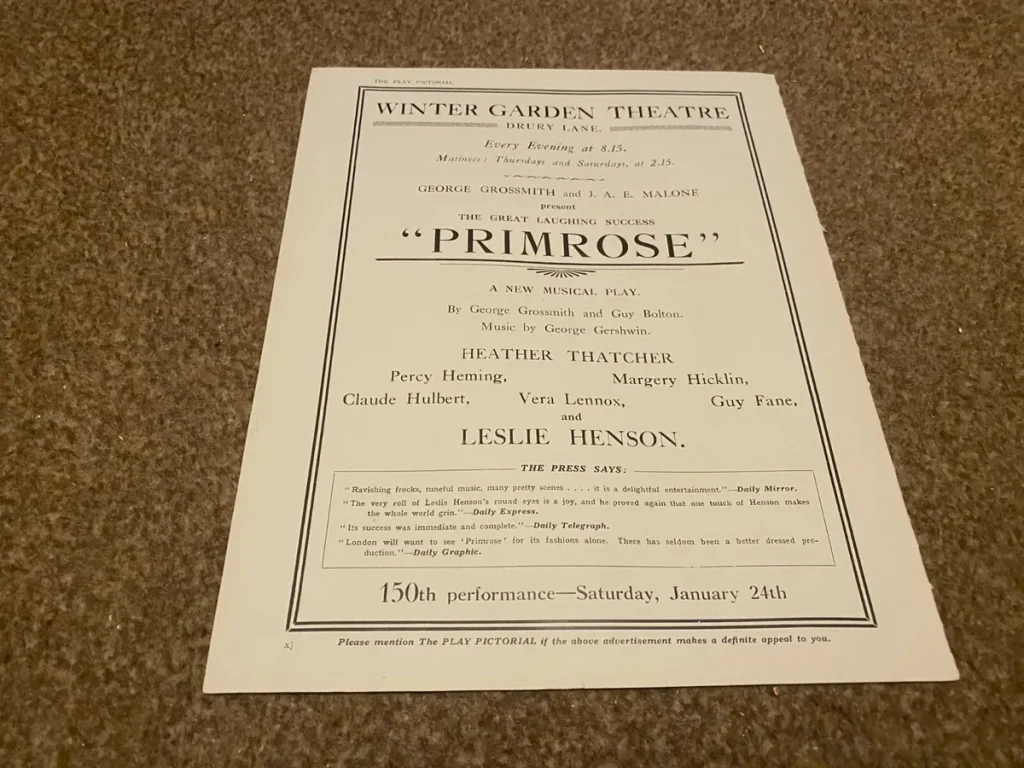

Thatcher played the feminine lead in London stage productions like Oh Daddy and Warm Corner. At the London Winter Garden she sang and danced in a revue in 1923. In August 1926, she appeared in Thy Name Is Woman at the Q Theatre. It marked her graduation from musical comedy to serious acting.

She continued her London stage work, performing with June Clyde in Lucky Break. Premiering at the Strand Theatre in September 1934, the theatrical presentation was a production of Leslie Henson. In 1937, Thatcher went to America in Full House. The previous season, she was paired with Ivor Novello in the English rendition. Jack Buchanan, Austin Trevor andCoral Browne teamed with Thatcher in Canaries Sometimes Sing (1947). Produced by Firth Shephard, the theatrical presentation opened in Blackpool and moved to London a month later. Thatcher participated in a Salute To Ivor Novello at the London Coliseum in September 1951. The production raised funds to run his old home, Redroofs. It had been purchased by the Actors’ Benevolent Fund.

The Plaything (1929), produced by Castleton Knight and Elstree Studios, begins as a silent film. It develops into an audible film which is recorded in good quality for its time. The theme concerns a Highland laird who falls in love with a hedonistic London heiress. Thatcher plays a prominent role as Martyn Bennett.

In 1931 she visited Hollywood while attending the wedding of James Gleason. As a star of English comedy, she was being compared to Marilyn Miller, Thatcher wore a monocle to the marriage ceremony. In the autumn of 1931 she was invited to a reception following the premiere of Strictly Dishonorable (1931), at the Carthay Circle Theatre. Among her friends in films were Anthony Bushell and Zelma O’Neal.

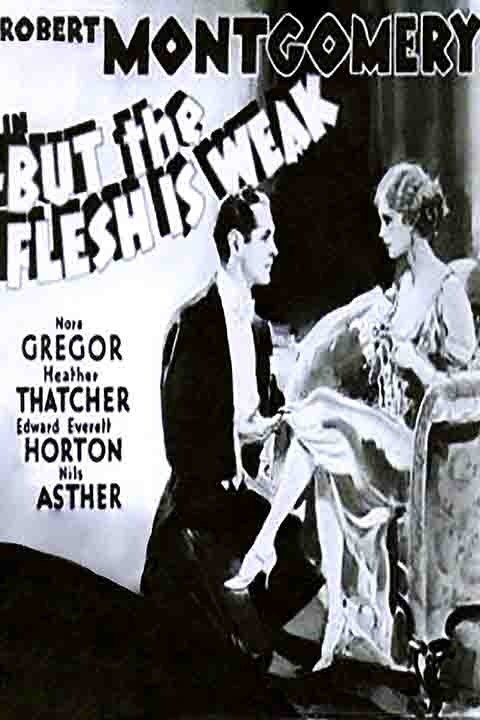

Thatcher was signed by MGM in February 1932. She was given a feature role in But The Flesh Is Weak (1932). The film stars Robert Montgomery and is directed by Jack Conway. The film was adapted from a British stage production which showcased Novello. Thatcher was praised for her performance. German actress, Nora Gregor was found disappointing. The English actress “gives a brilliant performance and creates the only human being in the piece.”

Thatcher sued Gloria Swanson British Productions for breach of contract in a suit which was settled in December 1933. During the filming of Perfect Understanding (1933) Thatcher’s contract was cancelled before the production was completed. No explanation was given. She was excluded from the film when a new author was hired. The replacement writer chose to eliminate her character.

The Private Life of Don Juan (1934) was also filmed at Elstree Studios. The film has Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. as its leading man. Owen Nares plays the title role and Thatcher is Anna Dora, one of the ladies.

Later in her career Thatcher returned to England to make films. Among these is Will Any Gentleman…? (1953), filmed at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood. Thatcher appears together with George Cole and Veronica Hurst. The film was a short adventure about a hypnotist who puts a man in a trance.

Thatcher made her last films in 1955. The Deep Blue Sea has a screenplay written by Terence Rattigan and features Vivien Leigh and Kenneth More. Thatcher depicts Aunt May Luton in Josephine and Men. The film is a comedy starring Glynis Johns and Peter Finch.

Thatcher died in Hillingdon, London in 1987.

The above “Wikipedia” entry can also be accessed online here.

“Wikipedia” entry:

Ronald Howard (7 April 1918 – 19 December 1996) was an English actor and writer best known in the U.S. for starring in a weekly Sherlock Holmes television series in 1954.[1] He was the son of actor Leslie Howard.

Howard was born in South Norwood, London, the son of Ruth Evelyn (Martin) and film actor Leslie Howard. He attended Tonbridge School. After graduating from Jesus College, Cambridge, Ronald Howard became a newspaper reporter for a while but decided to become an actor.

His first film role was an uncredited bit part in Pimpernel Smith (1941), a film directed by and starring his father in the title role, though young Howard’s part ended up on the cutting room floor. In the early 1940s, Howard gained acting experience in regional theatre, the London stage and eventually films, his official debut in While the Sun Shines in 1947. Howard received varying degrees of exposure in some well-known films, such as The Queen of Spades (1949) and The Browning Version (1951). Howard played Will Scarlet in the episode of the same name of the 1950s British television classic The Adventures of Robin Hood starring Richard Greene. The character of Scarlet was later portrayed by Paul Eddington.

The 1954 Sherlock Holmes television series, based on the Arthur Conan Doyle characters and produced by Sheldon Reynolds, ran for 39 episodes starring Howard as Holmes andHoward Marion-Crawford as Watson. In addition to 21st century DVD releases, in 2006 and 2014 this series was broadcast in the UK on the satellite channel Bonanza.

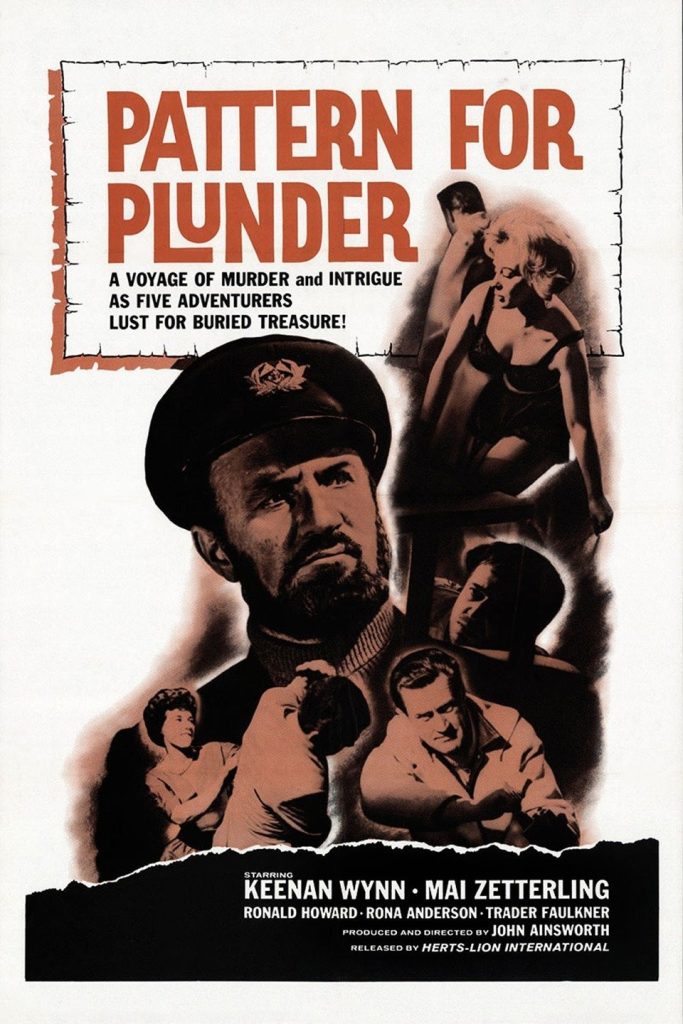

Howard continued mainly in British “B” films throughout the 1950s and ’60s, most notably The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964), along with a few plum television guest roles in British and American television in the 1960s, including as Wing Commander Hayes in the 1967 Cowboy in Africa TV show with Chuck Connors and Tom Nardini. In the mid-1970s, he reluctantly put aside his acting career to run an art gallery.

In the 1980s he wrote a biography covering the career and mysterious death of his father, whose plane was shot down over the Bay of Biscay on 1 June 1943. His conclusion (which remains in dispute) was that the Germans’ goal in shooting down the plane was to kill his father, who had been travelling through Spain and Portugal, ostensibly lecturing on film, but also meeting with local propagandists and shoring up support for the Allied cause.[2] The Germans suspected surreptitious activities since German agents were active throughout Spain and Portugal, which, like Switzerland, was a crossroads for persons from both sides of the conflict, but even more accessible to Allied citizens.[3] The book explores in detail written German orders to the Ju 88 Staffel based in France, assigned to intercept the aircraft, as well as communiqués on the British side that verify intelligence reports of the time indicating a deliberate attack on Howard.[2] Ronald Howard was convinced that the order to shoot down the airliner came directly from Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, who had been ridiculed in one of Howard’s films, and who believed Howard to be the most dangerous British propagandist.

The above “Wikiupedia” entry can also be accessed online here.

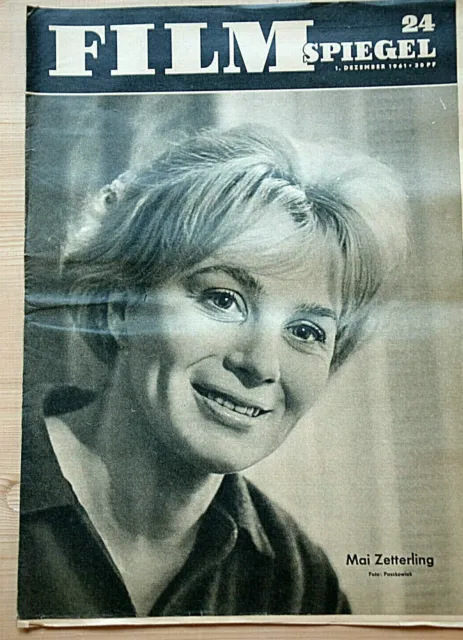

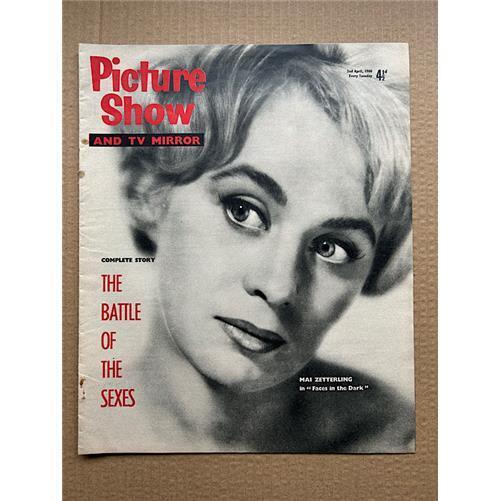

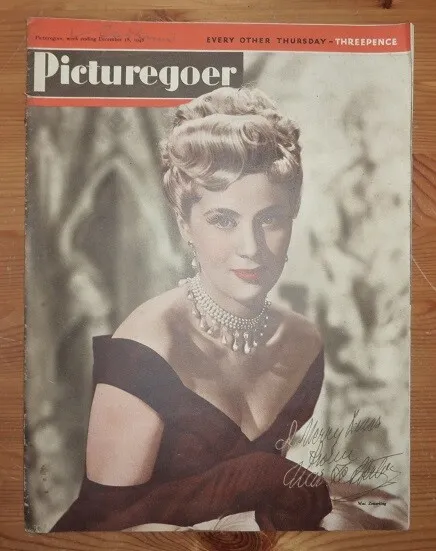

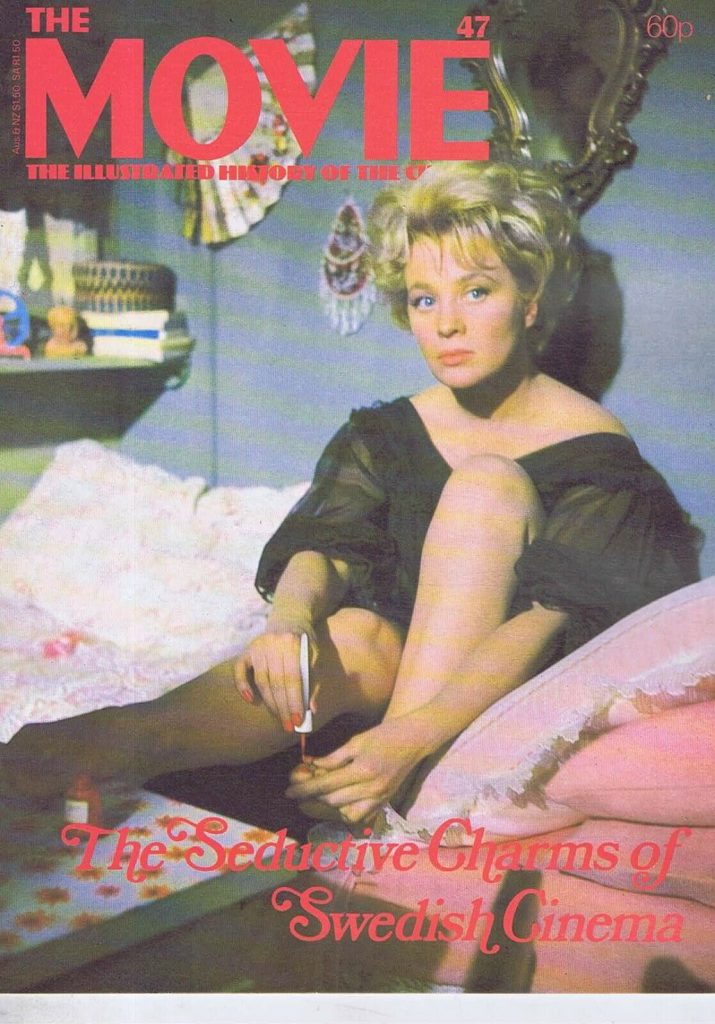

David Shipman’s obituary of Mai Zetterling in “The Independent”:

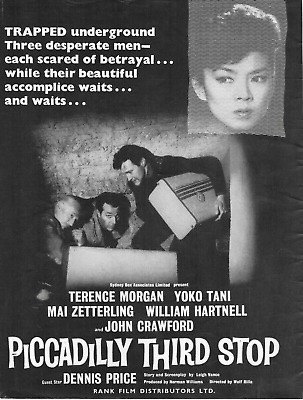

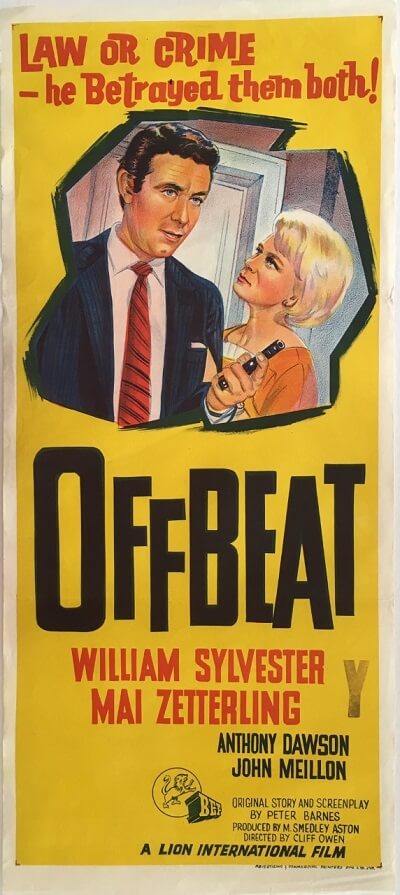

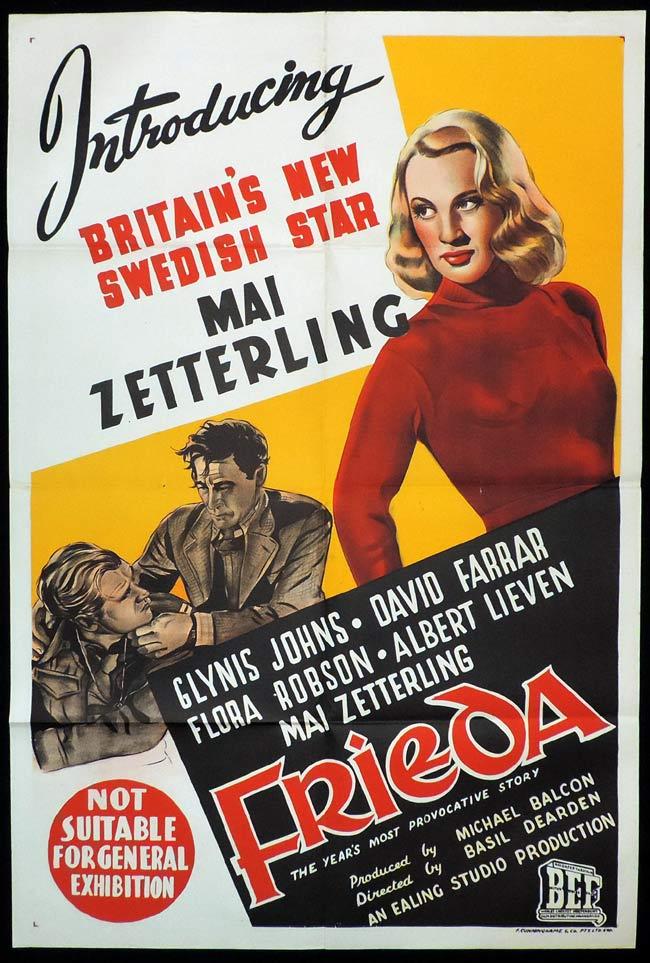

‘WOULD you take Frieda into your home?’ So went one of the most famous movie ad-lines of the post-war period. Frieda (1947) was the story of a German war bride and the prejudice she encountered when her husband, played by David Farrar, brought her home to the small town where he lived. It was directed by Basil Dearden for Ealing, a studio much admired for tackling topical issues.

Ealing might have argued that her notices for Hets (Frenzy, 1945) had proved that the critics adored her – she was certainly much admired for her performance as Bertha, the tobacconist’s assistant who seduces the schoolboy hero (Alf Kjellin) while pursuing his sadistic teacher (Stig Jarrel). It was written by Ingmar Bergman – his first work in movies – for the established Alf Sjoberg, who reunited his two young stars in Iris och Lojtnantishjarta (Iris).

Bergman, meanwhile, had become a director and cast Zetterling in Musik Morker (Night Is My Future/ Music Is My Future, 1948), in which she again played a maid who falls in love with the young master, Birger Malmsten. Though melodramatic, the film contains early echoes of Bergman’s richness.

Trained, like Ingrid Bergman, at the Royal Dramatic Theatre School in Stockholm, Zetterling might have sought a career like hers in the United States, but there were probably not sufficient roles for two leading Swedish actresses. Ealing, however, believed that Zetterling could be a big star for them. This was the heyday of period romances and the studio’s first Technicolor film was to be Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948), based on a novel by Helen Simpson about the adulterous affair between a Swedish mercenary (Stewart Granger) and Sophie Dorothea, the consort of the Elector of Hanover who became George I. But when Zetterling became pregnant the role went to Joan Greenwood.

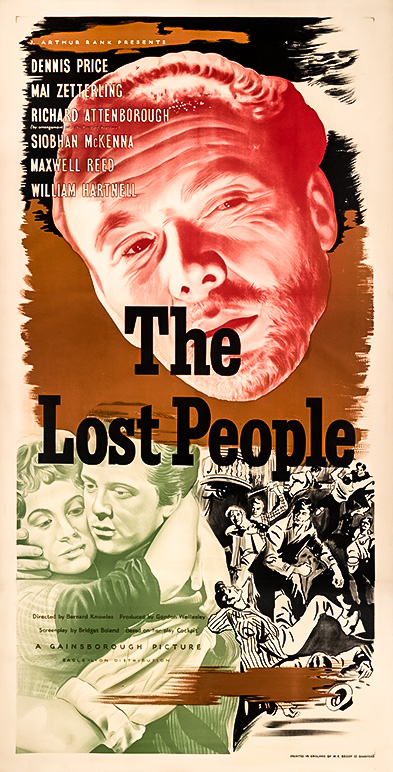

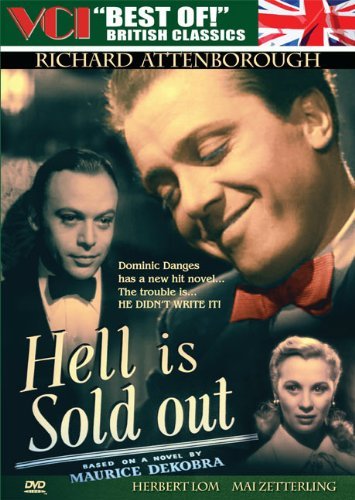

Zetterling looked like being a leading British star and in rapid succession played displaced persons in two movies set in contemporary Germany, Terence Fisher’s Portrait from Life (1948) and Bernard Knowles’s The Lost People (1949). These were produced by Gainsborough, smarting from the knowledge that critics disliked their escapist entertainment. Aiming again at respectability the studio came up with The Bad Lord Byron (1949), directed by David MacDonald with Dennis Price in the title-role, in which Zetterling played Byron’s Italian mistress Teresa Guiccioli. In what had been her second British picture Quartet (1948), a collection of four Somerset Maugham short stories, Zetterling had been unconvincing as a Riviera adventurist in the first of them, The Facts of Life. The Romantic Age (1949) was such sub-standard farce that it seriously damaged her film career.

However, the touching talent displayed in her Swedish films and Frieda found a congenial home on the West End stage. She had played supporting roles in classical plays in Stockholm; in London she scored such a critical success as Hedwig in The Wild Duck that the limited run of two months sold out the day after the first night. Later in 1948 Tennants cast her as Nina in The Seagull, with Paul Scofield as Constantin and Isabel Jeans as Arkadina, initially at the Lyric, Hammersmith, and then in the West End. Also at the Lyric for Tennants, she gave strong and subtle performances in Jean Anouilh’s Point of Departure (1950), as Eurydice to Dirk Bogarde’s Orpheus, and in A Doll’s House (1953), as Nora. She returned memorably to this theatre in 1959 to play Strindberg’s Tekla in Creditors.

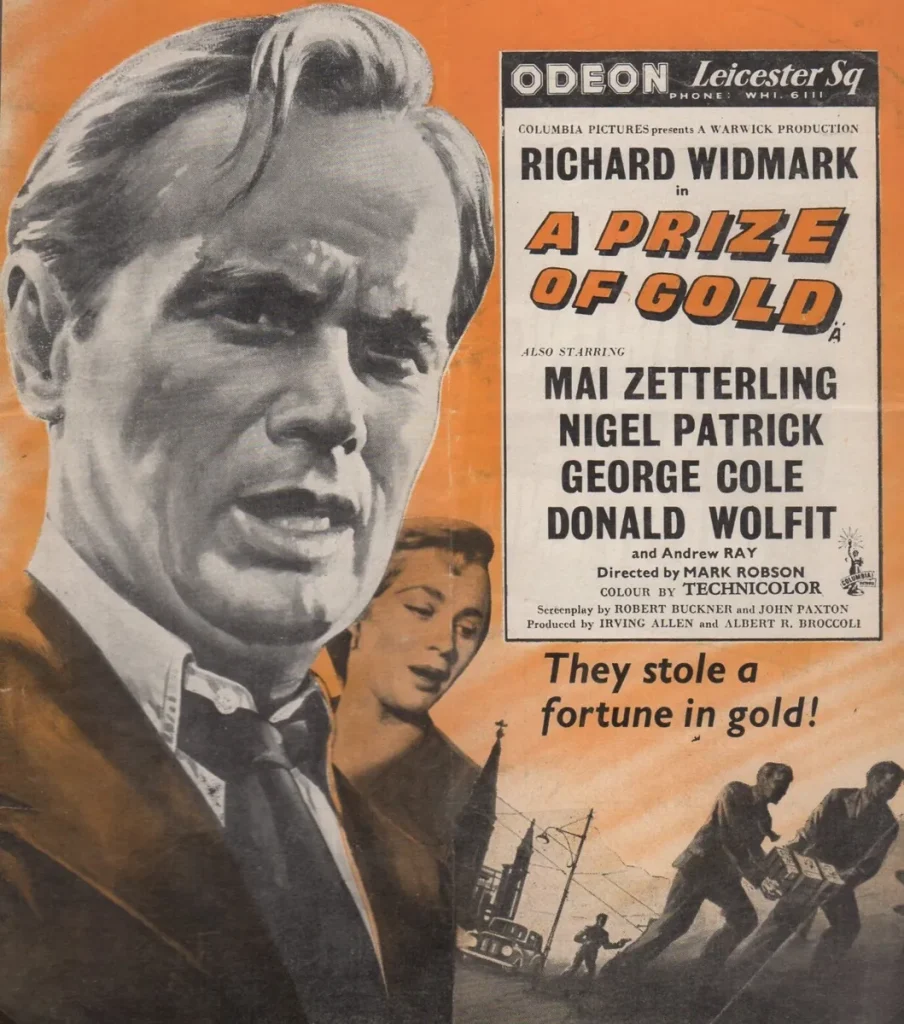

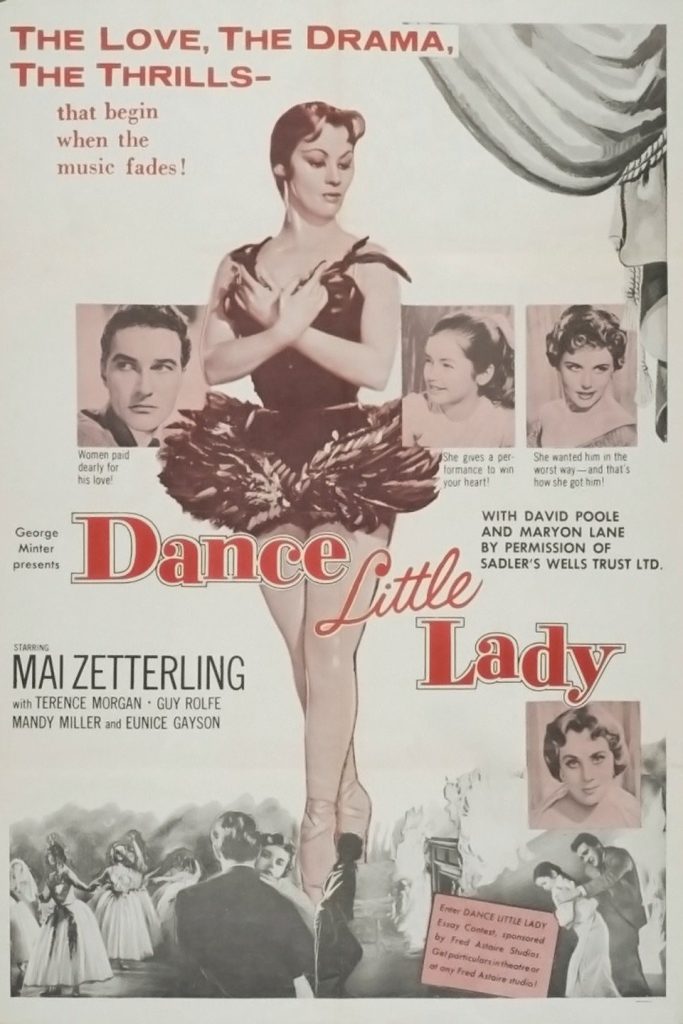

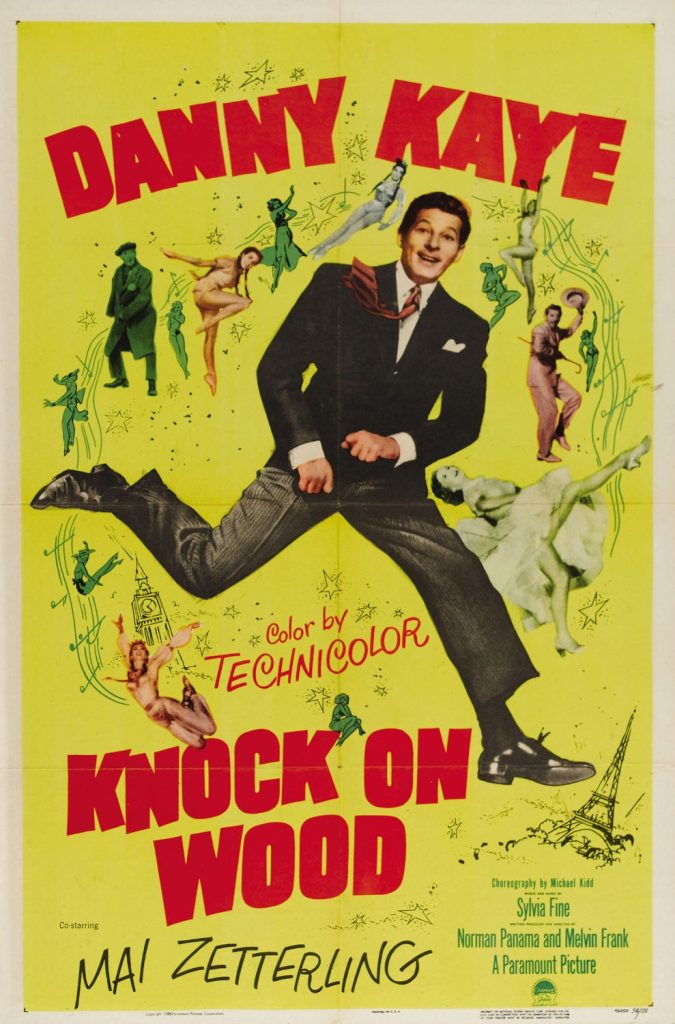

In the meantime Hollywood had called and she starred opposite Danny Kaye in Knock on Wood (1954), playing a Swiss psychoanalyst who follows him to London to continue to treat him. She became romantically involved with Kaye, as she did with Tyrone Power when he came to Britain to make Seven Waves Away; she also persuaded him to play opposite her in the television Miss Julie.

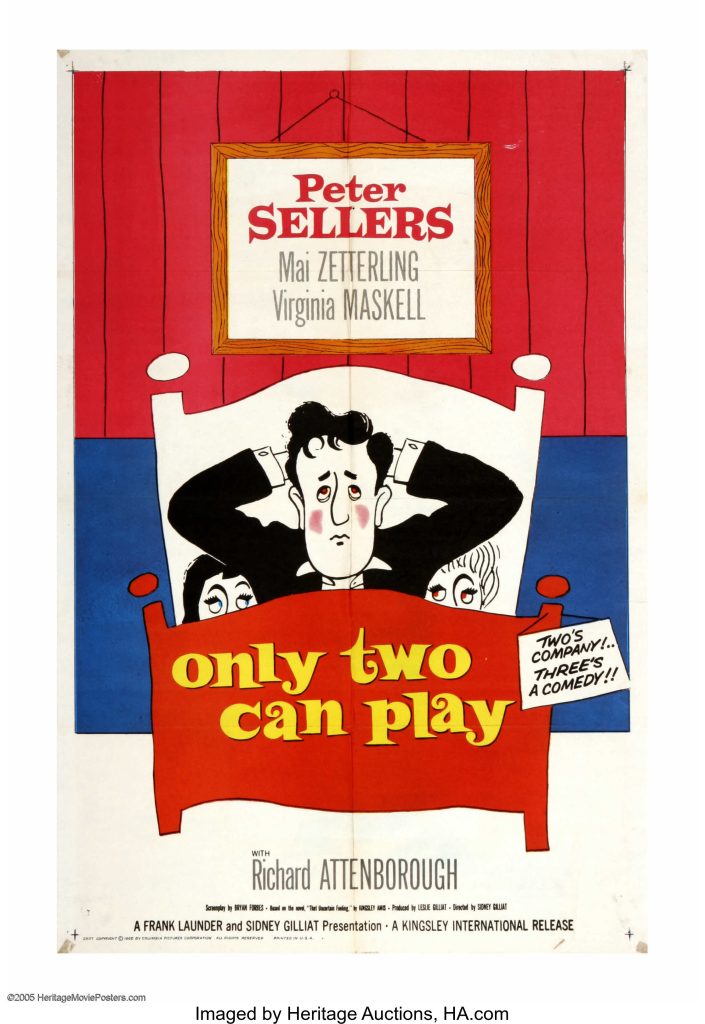

There were several other British movies, some of them backed by Hollywood: and although most of them were undistinguished she remained a ‘name’ throughout the world. Her last leading role at this time was one of her successful seductresses, the provincial wife who makes a play for the librarian Peter Sellers in Sidney Gilliat’s Only Two Can Play (1961).

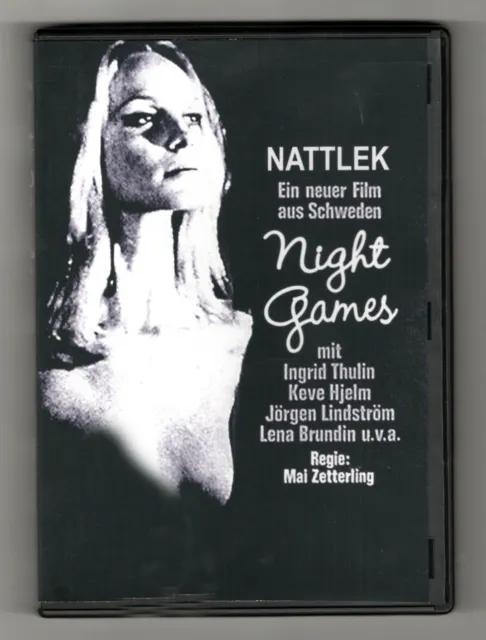

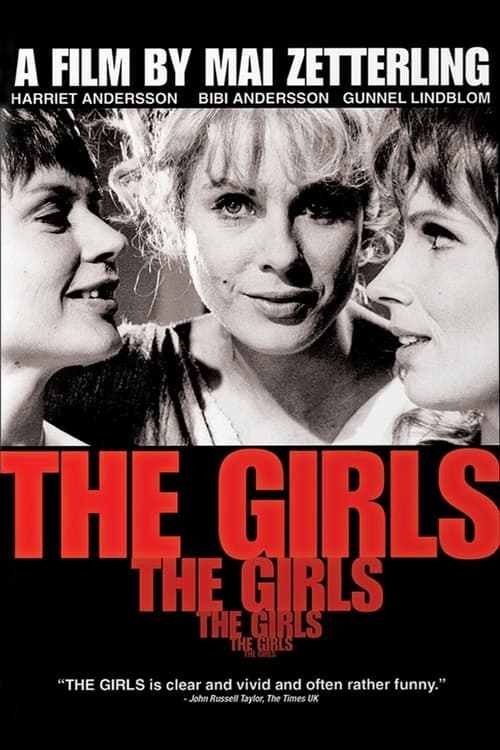

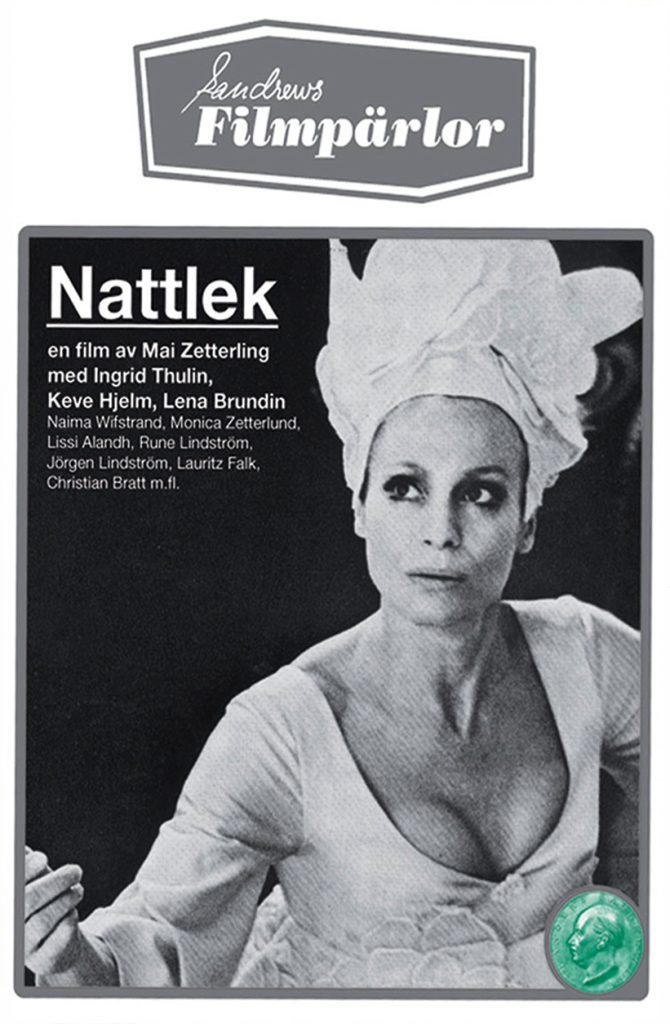

Zetterling, a woman of intelligence and fierce independence, decided not to sit around and wait for offers. She directed a short documentary, The War Game (1963), which won a Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. She returned to Sweden to direct Alskande Par (Loving Couples, 1964), a story of expectant mothers strongly influenced by Bergman and acted by some of his stock company, and Nattlek (Night Games, 1966), influenced this time by Strindberg as a disturbed man recalls his mother-dominated childhood. She also wrote the first of these, with her then husband, the novelist David Hughes, and the second she wrote alone from her own novel.

She continued to direct in Sweden and as her films became more feminist and more explicit they did not attract an undivided army of admirers. A British picture about two Borstal girls, Scrubbers (1982), created much controversy. Her last two films as an actress were Nicolas Roeg’s The Witches (1989) and Hidden Agenda (1990), Ken Loach’s brave film about Northern Ireland. That was only a small role, playing an anti-British activist, but one of which she was proud.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

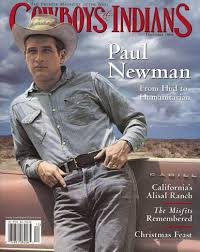

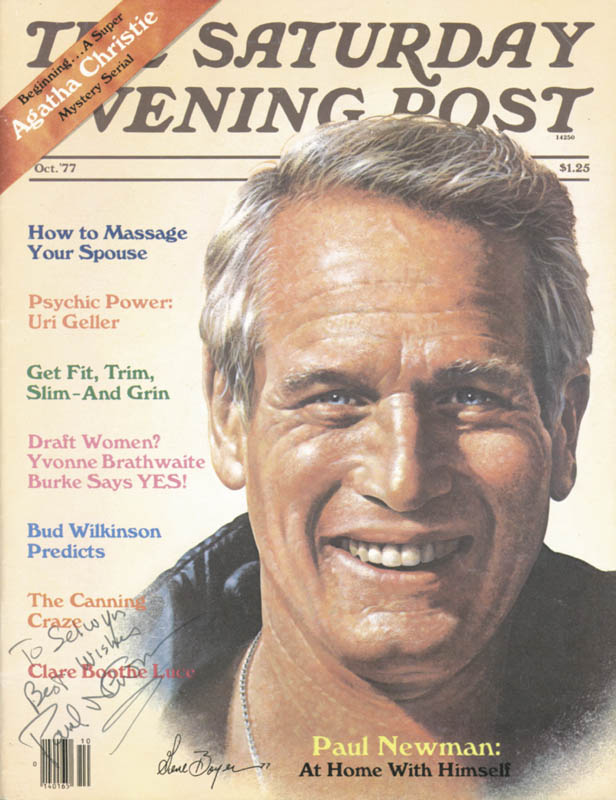

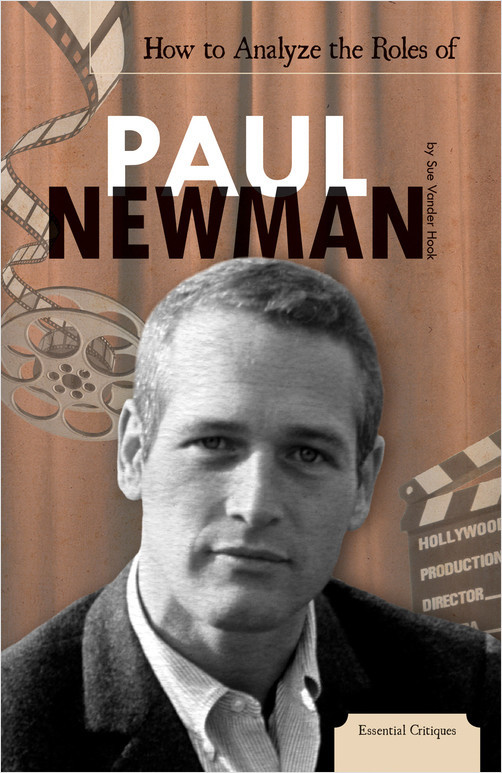

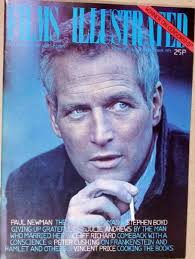

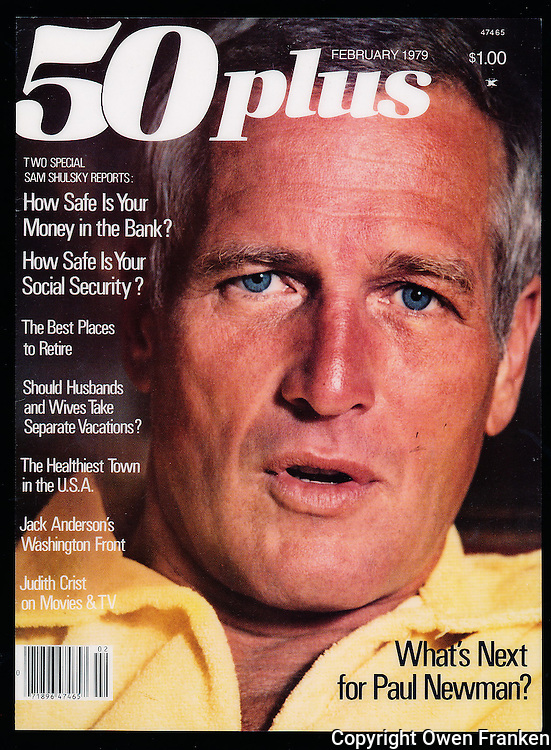

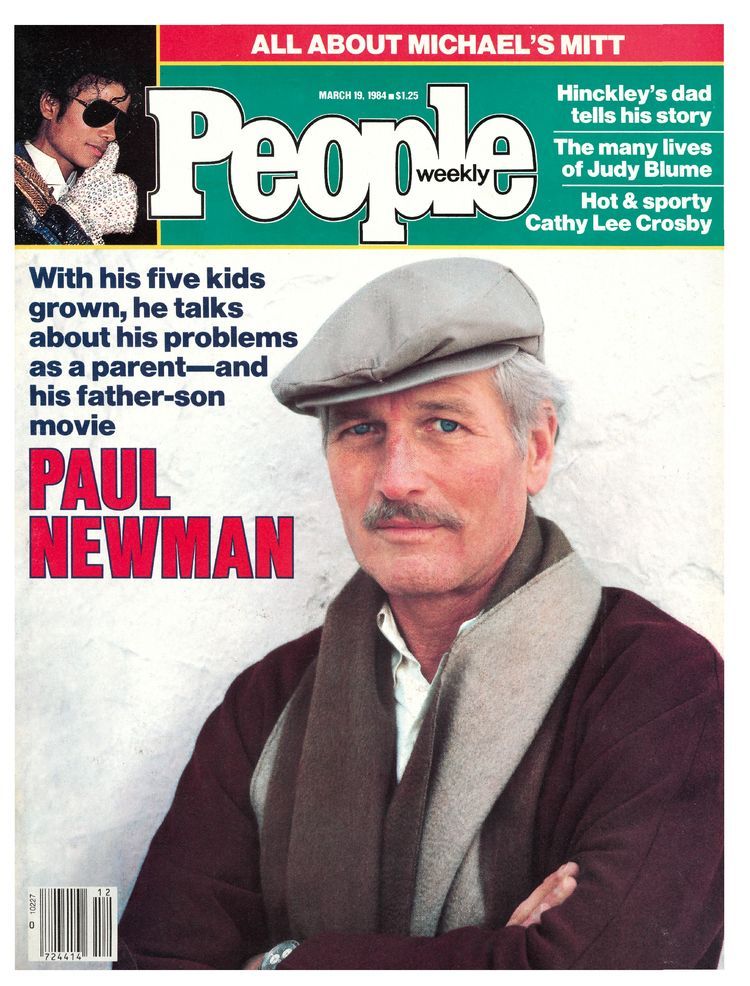

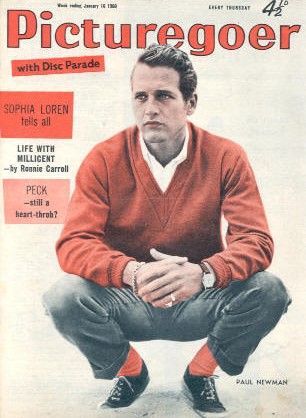

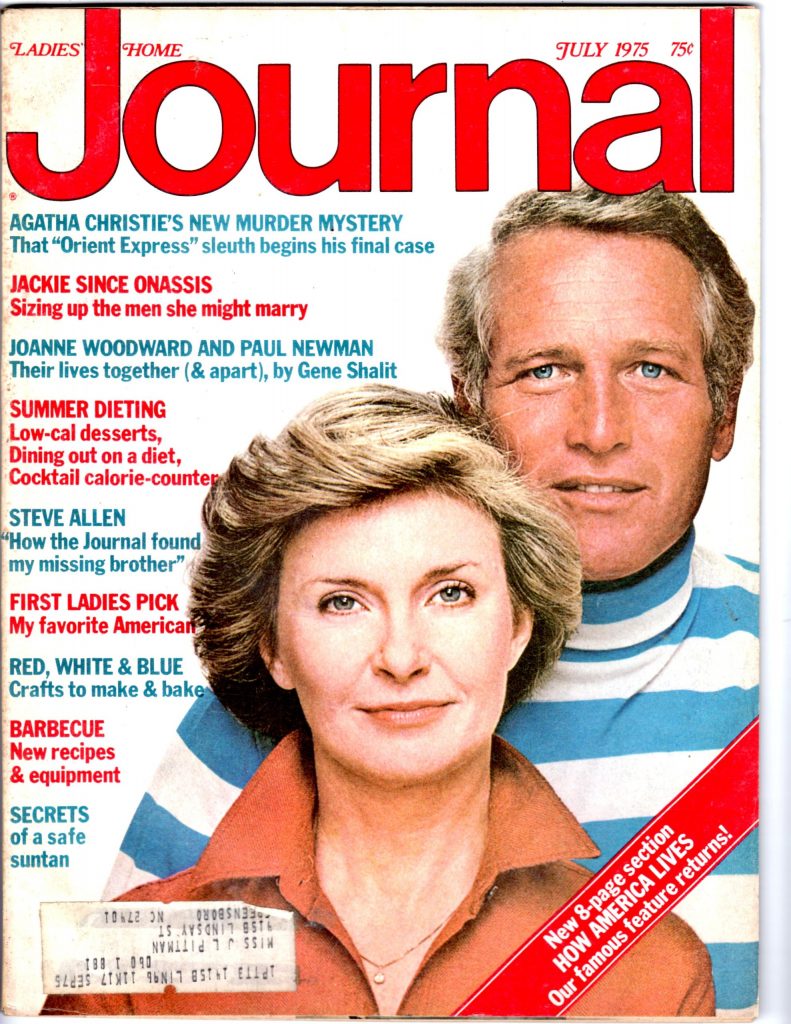

Paul Newman’s 2008 obituary in “The Guardian”:

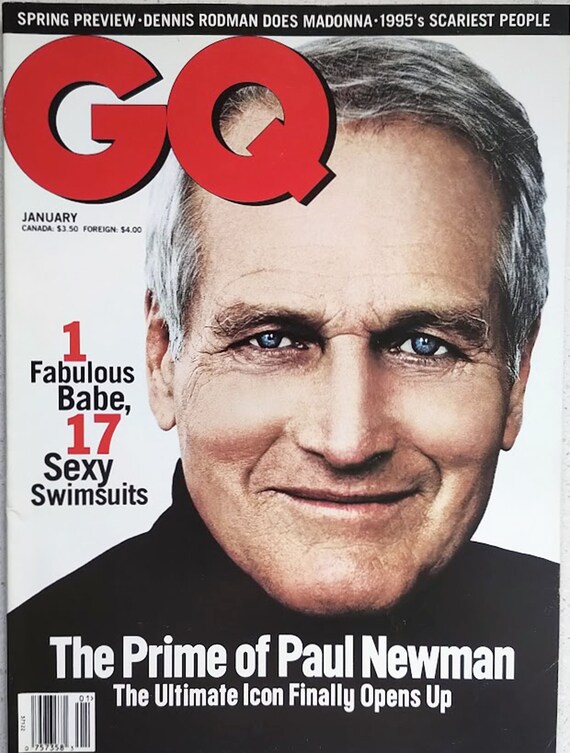

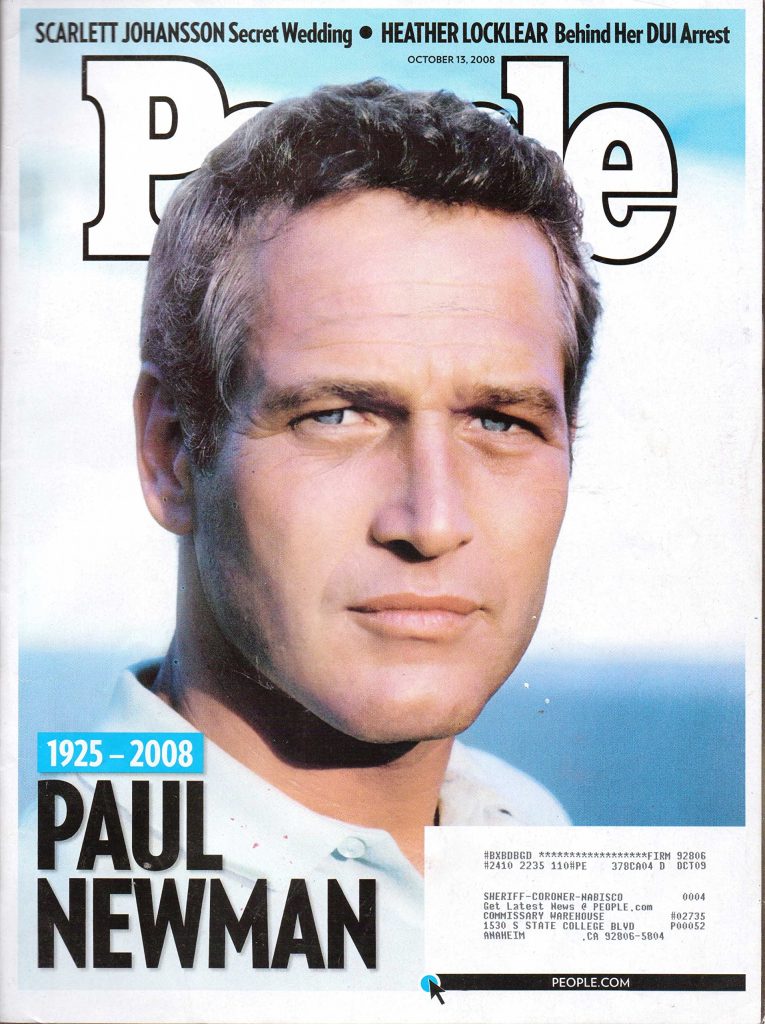

The actor Paul Newman, who has died aged 83, became so famous for his dazzling looks, and the bluest eyes in the business, that it is impossible to think of him as other than a celebrity.

Yet his many faceted, contradictory character renders the star image superficial. He was also a notable producer-director, a racing car enthusiast, a political activist and a philanthropist, counted as the person who had distributed more money – in relation to his own wealth – than any other American during the 20th century.

He claimed to be happiest behind the wheel of a racing car and noted that his athleticism found its perfect outlet in this sport. As a producer and co-founder of several companies, he was responsible for many of his own films and directed six features, four of them starring his second wife, Joanne Woodward. One of these gained him an Oscar nomination — one of eight, although he waited until 1986 for the coveted best actor statuette. He received two other Academy Awards, an oddly premature lifetime achievement award in 1985 and the Jean Herscholt award for his philanthropic work in 1993.

It is possible that this work may outlive his other achievements. In 1982 he founded – initially as a modest venture – the company Newman’s Own, producing products such as pasta sauces based on his own home recipes. He devoted the company’s entire profits – around $250m to date – to causes throughout the world.

Newman was actively concerned with some of the projects, including the Hole in the Wall Gang summer camps, devoted to underprivileged youngsters. He never gave up social concerns, and, in 1999, returned to the theatre in the two-hander Love Letters, where he and his wife raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to help land conservation in Connecticut.

He found time for political activities, including donating $1m to the leftist magazine The Nation, long-term involvement in civil rights issues and support for Democratic candidates. That said, his fame inevitably rested on his screen career. The star of more than 50 features, including 11 opposite Woodward, Newman, with his blue eyes, insouciant smile, and a handsome and eternally slim figure, was the idol of countless fans. His characters, such as the leads in Hud (1963) and Cool Hand Luke (1967) made him internationally famous and allowed him to enjoy the comfortable, although unostentatious, lifestyle available only to the very rich, with a main home in Connecticut, a Manhattan penthouse and a base in California.

Newman was born in Shaker Heights, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, the younger son of a sports store owner. His father was of Jewish-German descent and his mother was a Catholic whose family came from Hungary. She became a Christian Scientist when Paul was just five but her new beliefs did not impinge on the family and later in life Newman chose to follow none of their beliefs but, when asked, opted “for Jewishness because I considered it more challenging”.

His acting debut, aged seven, was as the court jester in Robin Hood at school. He left Shaker Heights high school in 1943 and went on briefly to Ohio University, in Athens, where he was expelled, supposedly after an incident involving a keg of beer and the rector’s car.

His comfortable life and good looks were proving a mixed blessing and wayward behaviour ended in trouble for drunkenness; there were even a couple of very brief stints behind bars. He had a lifelong liking for practical jokes.

From 1943 to 1946 Newman served as a US navy torpedo bomber radio operator. He graduated from the liberal arts Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, in 1949 and that year married for the first time — to Jacqueline Witte — and returned to Cleveland to manage the family store. His father died in 1950. But his destiny was to be an actor and he and his wife and son moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where Newman attended Yale Drama School. He had ambitions to be a drama teacher, but he was spotted at Yale by New York agents, moved to New York and had a period at the Actors’ Studio. He did a lot of television in that decade, debuting in an episode of the science fiction series Tales of Tomorrow in 1952. More importantly, chance led to a highly successful Broadway debut, originally as an understudy, in William Inge’s play Picnic (1953-54) — where he met another understudy, Woodward.

By then Hollywood had beckoned, but its call came via one of the most calamitous screen debuts ever recorded. The Silver Chalice (1954) miscast him in a toga, and so dismayed him that years later he paid for advertisements urging viewers not to watch it on television. He learned one valuable lesson — “avoid frocks” — and concentrated (except for westerns) on modern characters, often those under stress. There were few conventional romantic roles or comedies.

Recovery from his disastrous movie debut came back on Broadway in 1955, playing a gangster in The Desperate Hours. There was also plenty of television, including The Battler (1955), a Hemingway adaptation, directed by Arthur Penn, with Newman as a brain-damaged boxer, and a baseball story, Bang the Drum Slowly (1956).

Back in Hollywood he had famously lost out to James Dean when Elia Kazan screen tested them both for the lead in East of Eden. But in 1956, following Dean’s death, the role of the boxer Rocky Graziano — earmarked for Dean — in Somebody Up There Likes Me fell to him. That year, too, he starred as a brainwashed army officer in the post-Korean war drama, The Rack. Even the couple of duds which followed could not take the shine off his success. In 1957 Newman filmed The Long Hot Summer (1958), from a William Faulkner story, alongside Woodward. By January 1958 Newman was divorced from Witte, and had married his co-star.

Two more films that year confirmed his stardom. The Left Handed Gun featured Newman as Billy the Kid. They play on which it was based, written by Gore Vidal — a close friend of Newman and Woodward — had depicted Billy as gay. This theme became less explicit as the work filtered through TV, where Newman had first performed it in 1955, and in to Arthur Penn’s screen version where Billy’s relationship with his murdered mentor is left unclear.

The same thing happened with Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, where Newman played the tortured Brick opposite Elizabeth Taylor’s Maggie. As on Broadway, the homosexual theme was obscured and the reason for Brick’s marital chaos never made clear. Newman meanwhile won an Oscar nomination. In 1959 he returned to Broadway, and Tennessee Williams, in Sweet Bird of Youth. After that he effectively abandoned the theatre for 33 years, to the dismay of his wife, who believed that stage discipline would make him less reliant on his charm and the mannerisms that were — for some critics — becoming over-familiar.

In 1960 Newman starred in Otto Preminger’s vast and lumbering epic about the birth of Israel, Exodus. A year later he played a jazz musician in the intriguing Paris Blues.

Sadly, over the course of his career Newman worked with few major directors on their best films. His work with Alfred Hitchcock, Martin Scorsese, John Huston and Robert Altman was on their lesser movies. The great exception was Robert Rossen, whose classic adaptation of Walter Tevis’s novel The Hustler (1961) gave Newman his most complex early role and marked a turning point in his career. As Fast Eddie, a poolroom shark, whose innate corruptness leads to a brutal come-uppance, Newman crystallised his screen persona — a blend of vulnerability and bravado, criminality and redemption — in a performance of new found maturity. It was left to Bafta to give him its award as best actor, while the Academy passed him over for the second time. It was not until he played Eddie again opposite Tom Cruise in The Color of Money (1986) that he received the Oscar.

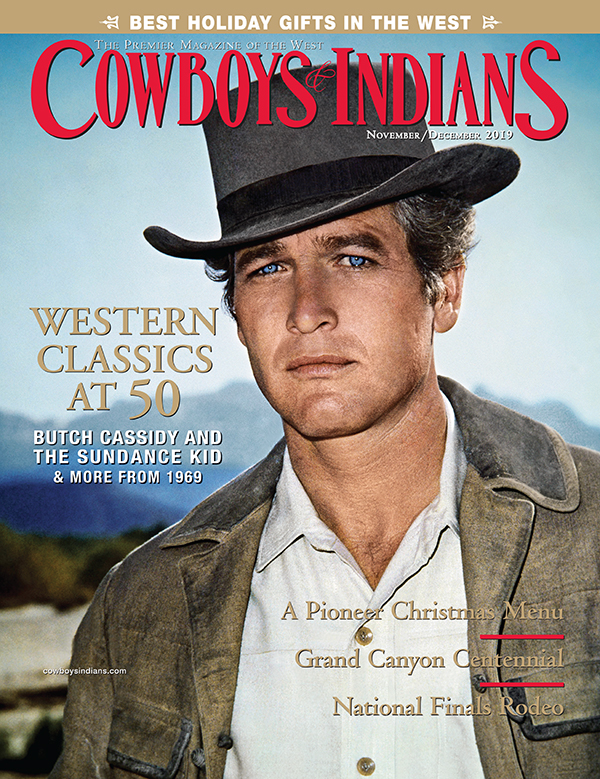

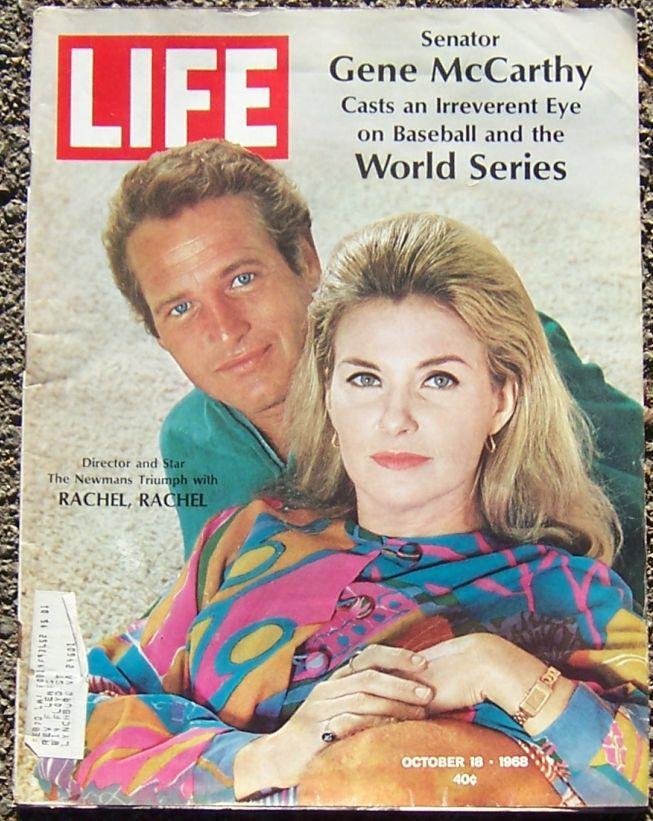

Rossen aside, Newman fared better — especially in commercial terms — with sturdy middleweight talents such as Sidney Lumet, Martin Ritt and Richard Brooks in films where what the critic Andrew Sarris memorably described as “strained seriousness” seemed to suit Newman’s own demeanour. The Hustler initiated the period that brought Newman fame and fortune, in title roles that became part of cinema legend — among them Ritt’s Hud (1963), Harper (1966), Cool Hand Luke (1967) and Butch in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) with Robert Redford. In 10 years he starred in 18 films, as well as directing his first and best movie, Rachel, Rachel (1968), starring Woodward.

Curiosities of that period included a reworking of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, retitled Outrage (1964), in which the Japanese bandit is transposed to Mexico. Newman relished another character role in an intelligent western, Hombre (1967), directed by Ritt from an Elmore Leonard story. It was compensation for Peter Ustinov’s Lady L (1965) with Sophia Loren, the Hitchcock cold war thriller Torn Curtain (1966), opposite Julie Andrews and the comedy The Secret War of Harry Frigg (1968).

He looked far happier in the Indianapolis 500 motor racing drama Winning (1969), by which time his fee for any one of his numerous movies far exceeded the $500,000 he had paid years before to extricate himself from a studio contract. Importantly, the choices he made were his own, even if there were, inevitably, duds along the way.

Many characters which he played to popular acclaim were less than admirable. Hud is selfish, Luke arrogant, Harper callous and Butch a killer. Other characters were self-obsessed (the racing driver) or wilful and on the margins of society. To such creations, even mean spirited ones, he brought a strength that made him — alongside Brando — the acceptable anti-hero of the period.

By the 1970s Newman had become more overtly political. He was one of the narrators of the documentary King: a Filmed Record … from Montgomery to Memphis (1970), about Martin Luther King, and also in that year starred in the anti-radical right drama WUSA. His support for the King documentary was one aspect of his support for civil rights. He also campaigned against the war in Vietnam and had supported Eugene McCarthy’s 1968 bid for the presidency. He was vigorous in his opposition to Richard Nixon and proud of being among the top 20 on Nixon’s “most hated” list.

Newman never lost his commitment to liberal causes, but like his exact contemporary Charlton Heston, whose raucous support for the gun lobby, and the right, diametrically opposed Newman’s philosophy, he found that overt politicising sometimes misfired. People came to see him, not always to support the cause. He found greater satisfaction as part of the team involved with his charitable foundation.

At the height of his fame Newman formed one of several production companies he was to be associated with. Barbra Streisand, Sidney Poitier, Steve McQueen and later Dustin Hoffman joined him to set up the First Artists title in 1969. Each agreed to make three movies and Newman — possibly with less ego than most of his partners — fulfilled his promise.

In 1972, Pocket Money revived his Luke character in all but name. He then made The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, distractedly directed by his friend Huston during the early throes of one of his many marriages. Finally, in 1975, he revived the Lew Harper detective in a rather sadistic thriller, The Drowning Pool. Soon after, First Artists was wound up and the actor found himself looking for roles that suited a star now into handsome middle age.

His box office credibility had been maintained by two smash hits The Sting (1973), which reunited him with Redford, and The Towering Inferno (1974), where he received top billing.

Of his two films with Robert Altman, Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or, Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976) is by far the more successful, but the bizarre futuristic drama Quintet (1979) ended the decade disastrously, a flop compounded by the awfulness of When Time Ran Out (1980). His fans had not taken to the raucous and foul-mouthed Slap Shot (1977), another work which had indicated Newman’s search for more original material.

He had returned to direction in 1971, salvaging the outdoor drama Sometimes a Great Notion. The following year he produced and directed a vehicle for his wife and daughter Nell, The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds. He was to render her better service 15 years later when he directed The Glass Menagerie (1987), “to immortalise Joanne’s performance”. His other stints as director were a competently made television film, from the play The Shadow Box (1980), and four years later a more personal work Harry & Son. This movie, which gave him his only writing credit (plus star, producer and director), was a highly charged family drama about the difficult relationship between Harry and his teenage son.

The subject was almost too close to Newman, whose first child Scott had died of a drug overdose in 1978. Newman felt deeply distressed by his death and the overwrought Harry & Son meant more to its creator than to the general audience.

During the 1980s Newman settled into character roles and in 1981 enjoyed success as a tough street cop in Fort Apache, the Bronx. But the cop, like his crane driver Harry, asked us to believe in Newman as a working-class hero and lacked the credibility he brought to Absence of Malice (1981) and The Verdict (1982). Both earned him Oscar nominations. The latter had a screenplay by David Mamet and presented him with a juicy role as a fading, alcoholic lawyer. A part which, as his director Sidney Lumet remarked, required only minimal research.

The star had an acknowledged taste for alcohol and despite giving up spirits in mid-career (with a lapse after his son’s death), enjoyed his beer and displayed a deep appreciation of vintage wine. I recall having lunch with him one day at his London hotel suite when he particularly liked a white Burgundy. He called the restaurant and ordered the rest of the case to be put in his refrigerator.

Bizarrely, his intense performance in The Verdict failed to gain him an Oscar — a fact taken harder by his wife than by the star. It was suggested that his politics and residence on the east coast since 1962 had alienated him from the conservative Hollywood establishment. In compensation — after he had taken a year off to concentrate on his motor racing — he was awarded, aged 60, an honorary Oscar for his lifetime achievement, normally reserved for the truly venerable within the profession. The following year he chose not to attend the awards ceremony — only to win best actor for The Color of Money.

Alongside the accolades, there were other less successful movies, such as Blaze and Fat Man and Little Boy (both 1989). In the former he starred as Earl Long, the philandering 1950s governor of Louisiana. His necessarily strident performance failed to ignite a dull movie. The second work personalised the story of General Groves, the belligerently professional officer who oversaw the Manhattan Project which developed the allied atomic weapons programme. Duller than either of these was Mr & Mrs Bridge (1990), in which he and Woodward wilted under James Ivory’s direction.

Newman took a long time out of acting and away from conventional Hollywood. Then, in 1994, he had a villainous supporting role in the Coen brothers’ satire on big business The Hudsucker Proxy and the lead in Nobody’s Fool. Both reminded audiences of his talent. In the latter, he played a grouch unable to relate to his own son but drawn to his shy grandson — a touching relationship which, the director Robert Benton noted, drew heavily on Newman’s own character. The performance gained him another Oscar nomination. Despite this success, he again stayed away from film work except to narrate Baseball (1994) and a 1997 TV series, Super Speedway.

In 1995, aged 70, he took part in the 24-hour Daytona endurance race — becoming the oldest person ever to complete the event, capping his 1979 success when he and his co-driver finished second in the 24-hour Le Mans race. After Daytona, he agreed to quit professional racing and to the relief of his wife opted for his Volvo.

Four years after Nobody’s Fool, Benton coaxed him back to the studio to star in Twilight (1998), to play an ageing, cynical private detective with a drink problem. The part was tailor-made for Newman, who brought a gravel-voiced and somewhat melancholy charm to the character. Despite a fine cast, the film had a tired feel to it and showed signs of severe post-production pruning.

The movie marked a flurry of activity for Newman and he followed it with Message in a Bottle (1999), a tear-jerker in which he played Kevin Costner’s crotchety, alcoholic father — scooping the best reviews, not least for his commanding presence, but also for a willingness to play his age. He again took third billing to decidedly lesser names in Where the Money Is (1999), proving, if proof were needed, that after decades of stardom he was a dedicated professional first and a star a long way second.

Newman returned to a substantial film role in Sam Mendes’s Road to Perdition (2002). He was cast atypically as the vicious gang boss Rooney who commits a murder witnessed by the small son of one of his henchmen (Tom Hanks). Set in the 1930s, the movie was heavy on atmosphere and menace, provided by Newman and his contract killer, Jude Law. It brought him yet another Oscar nomination and rave reviews.

No roles of similar quality followed, but back on stage he scored a hit in 2002 as the Stage Manager in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town and reprised it on television the following year, with Woodward as executive producer.

His final acting appearance was in the prestige television drama Empire Falls, directed by Fred Schepisi from the award-winning novel by Richard Russo, writer of both Twilight and Nobody’s Fool. He was executive producer and won an outstanding actor Emmy.

In 2007 he announced, “I think acting is pretty much a closed book to me.” Yet his voice could be still be heard on a number of short cartoons, as the character Doc Hudson, both in Cars and Mater and the Ghostlight, and finally the Indy Car Series Preview for 2008, showing that his love of motor racing had never left him. In June 2007, he donated $10m dollars from his charitable foundation to Kenyon College from where he had graduated all those years ago. The endowment created the largest scholarship in the history of the college, but it was just one more act that earned him the justified reputation as one of Hollywood’s good guys, as well as one of its greatest actors.

He is survived by his wife Joanne and their three daughters and two daughters from his first marriage.

Paul Leonard Newman, actor, born January 26 1925; died September 26 2008

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Steve Forrest’s “Guardian” obituary in 2013:

Steve Forrest, who has died aged 87, was a product of the Hollywood studio system, then at its tail end in the 1950s. Although MGM had the handsome, rugged 6ft 3in actor under contract for five years, from 1952 to 1957, they gave him few chances to shine. It was only when he left the studio that Forrest got bigger and better parts in feature films – one of his best performances was as the white brother of Elvis Presley, who plays the son of a Native American mother and a Texas rancher father, in Don Siegel’s excellent western Flaming Star (1960) – and he was able to start a long and busy career on television.

In fact, it was on the small screen that Forrest would build his fame, notably in S.W.A.T. (1975-76), a cop series set in Los Angeles, the acronym referring to the police department’s special weapons and tactics team. It ran for 37 episodes, with Forrest as a stern, level-headed Lieutenant Dan “Hondo” Harrelson, who would cry out “Let’s roll” as he climbed into a van to go on another mission to catch villains.

Forrest was born in Huntsville, Texas, one of 13 children of a Baptist minister. An older brother, 15 years his senior, was the more famous Dana Andrews, who was to become a leading man in films during the 1940s and 50s. It was through this older brother that Forrest got his first taste of the movie business when, aged 18, he had a bit part as a young sailor in Crash Dive (1943), which starred Andrews and Tyrone Power.

After serving as a sergeant in the army during the second world war, Forrest moved to Los Angeles to study at UCLA. He graduated in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in theatre arts and became a stagehand at La Jolla Playhouse, gradually getting roles. He resumed his postwar movie career with a small role in another of Andrews’s pictures, Sealed Cargo (1951).

But the following year, Forrest was able to distance himself from Andrews when he landed the MGM contract. At first he only had small parts, such as playing the actor in Lana Turner’s screen test in The Bad and the Beautiful (1952). He was glimpsed as a soldier in Battle Circus (1953), starring Humphrey Bogart and June Allyson, and played an army recruit under tough training sergeant Richard Widmark in Take the High Ground! (1953).

His first real parts came when he was loaned out to Warner Bros for two pictures. In So Big (1953), based on a sprawling novel by Edna Ferber, Forrest plays long-suffering Jane Wyman’s selfish son, for which he won a Golden Globe for most promising male newcomer. He was hardly able to fulfil his promise in the role of a scientist suspected of being a serial killer in Phantom of the Rue Morgue (1954), a feeble adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe.

Back at MGM, Forrest was given more substantial roles than previously. In Prisoner of War (1954), a simplistic “Red Scare” movie, Forrest was one of a group of brave American PoWs, including Ronald Reagan, being subjected to torture and brainwashing in a North Korean camp. When a brutal Soviet officer asks Forrest where his family lives, he replies: “In Hollywood with my brothers Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy and my sisters Esther Williams and Janey Powell.”

Much better was Rogue Cop (1954), in which a poker-faced Forrest plays a policeman who is honest, unlike his detective brother played by Robert Taylor in the title role. Forrest was finally given rare top billing as a young man studying for the priesthood in Bedevilled (1955), a quasi-religious thriller, and as the writer hero in Mexico in The Living Idol (1957), a risible synthesis of exotic romance and mysticism. According to the New York Times, “a pretty young man named Steve Forrest plays the reporter chap. He is purely ornamental until he goes into a bare-handed battle with a jaguar.”

Freed from his MGM contract, Forrest portrayed a New York reporter falling for a rural Doris Day in It Happened to Jane (1959), and in Heller in Pink Tights (1960) he played a gunfighter who wins blonde dancer Sophia Loren in a poker game, but loses her to Anthony Quinn. The latter role gave the often stolid Forrest an opportunity to show more ebullience.

In the meantime, he had established a parallel career on television, appearing notably in westerns such as Bonanza, Death Valley Days, The Virginian and Rawhide. In 1965, he and his family moved to London, where he starred in 30 episodes of the ATV series The Baron. Forrest was rugged and charming in the title role, the nickname given to John Mannering, a Texas-born, London-based antique dealer who is really a secret agent.

On the big screen, Forrest would have a key role as the lawyer boyfriend of Joan Crawford (Faye Dunaway) in Mommie Dearest (1981), a rather trashy melodrama in which he looked plainly uncomfortable, nor was he in his element as a heavy in the unfunny spoof Spies Like Us (1985).

He then returned to television, notably with 15 episodes of Dallas in 1986, playing Wes Parmalee, an impostor pretending to be Jock Ewing, and in several episodes of Murder She Wrote.

He is survived by his wife, Christine, and sons, Michael, Forrest and Stephen.

• Steve Forrest (William Forrest Andrews), actor, born 29 September 1925; died 18 May 2013

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

TCM Overview:

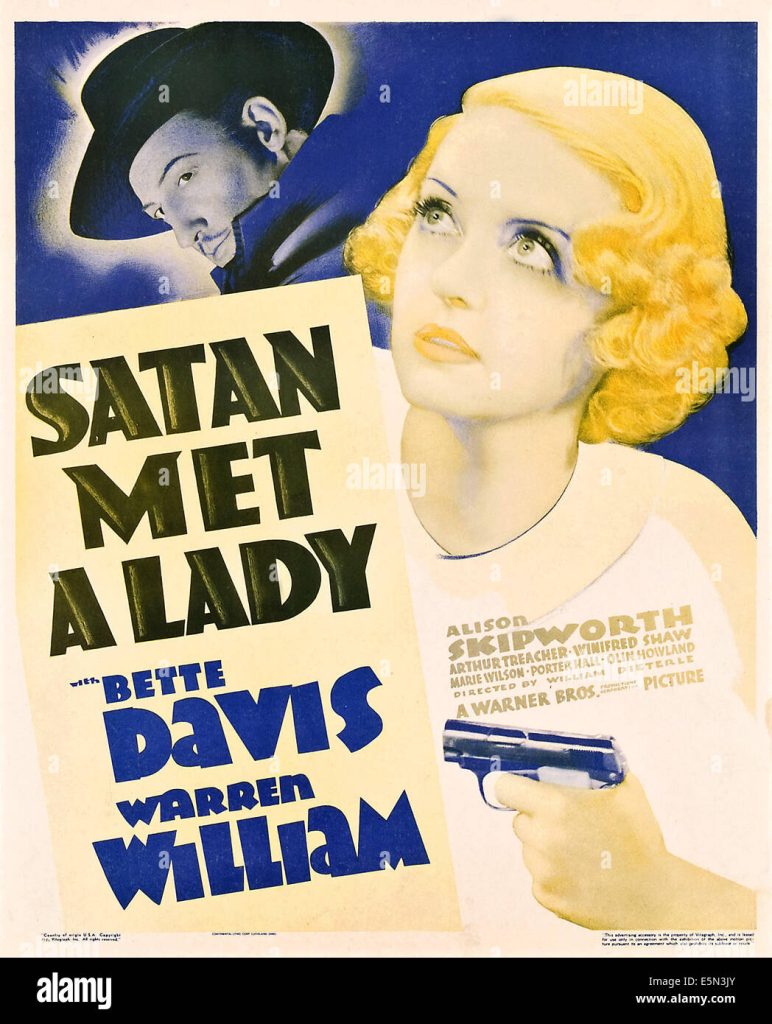

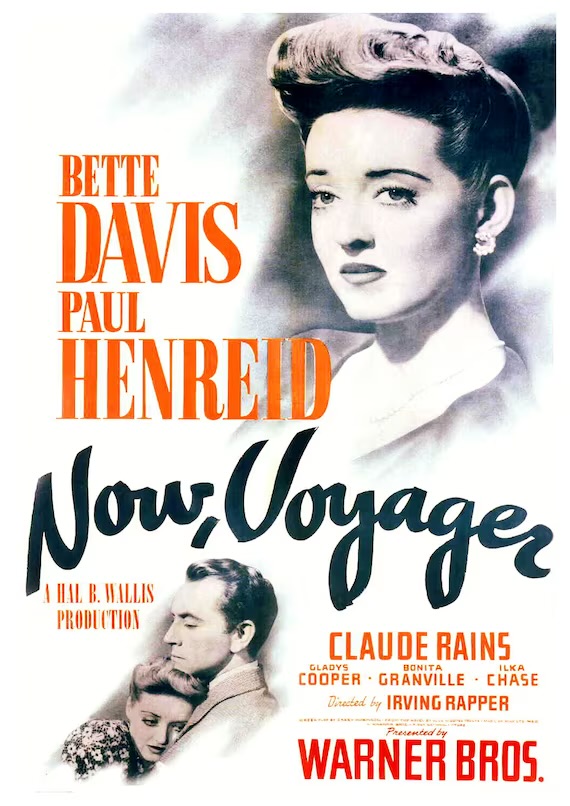

A strong-willed, independent woman with heavy-cast eyes, clipped New England diction, and distinctive mannerisms, Bette Davis left an indelible – and often parodied – mark on cinema history as being one of Hollywood’s most important and decorated actresses. Over the course of her storied career, Davis made some 100 films, for which she received 10 Academy Award nominations, and twice won the Best Actress trophy. But her sometimes over-the-top affectations – which no doubt made her a gay subculture icon – hindered her career despite the enormity of her talents. Not a glamorous star, Davis went through a string of forgettable pictures before tackling the rather unsympathetic Mildred in “Of Human Bondage” (1934), which turned her into a star and earned the actress her first Oscar nomination. She won the Academy Award the following year for “Dangerous” (1935) and later earned her second statue for one of her most famous performances in “Jezebel” (1938). By this time, Davis was a big star and went on to a series of box office hits like “Dark Victory” (1939) and “Now, Voyager” (1942). But after the personal tragedy of losing her husband, Arthur Farnsworth, Davis went into serious professional decline, only to resurrect herself with a delectably over-the-top performance in “All About Eve” (1950). Her resurgence was brief, however, as Davis once again was forced to accept a number of mediocre films while going through a number of personal travails. After emerging one last time with her Oscar-nominated turn in “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” (1962), Davis settled into a succession of film and television roles that culminated with her last acclaimed performance in “The Whales of August” (1987). Passing just two years later, Davis was remembered as one of Hollywood’s greatest actresses, a legacy forged by an iron will to go her own way.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

problems; we are continuing to work to improve these archived versions.

Bette Davis, who won two Academy Awards and cut a swath through Hollywood trailing cigarette smoke and delivering drop-dead barbs, died of breast cancer Friday night at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. She was 81 years old and lived in West Hollywood, Calif.

Miss Davis was en route to her home from the San Sebastian Film Festival in Spain, where she had been honored for her acting career. She arrived in Paris on Tuesday and was to fly to Los Angeles, but was taken instead to the hospital, on the outskirts of Paris.

Her lawyer, Harold Schiff, said she had undergone a mastectomy in 1983.

”The doctors had told us the cancer had spread, that it was terminal,” he said. ”The doctors had said let her go on going about her business.” #2 Oscars, 10 Nominations For more than a half century, Bette Davis reigned as a Hollywood star in the grandest meaning of the term. With her huge and expressive eyes, her flamboyant mannerisms and her distinctive speaking style, she left an indelible mark on her audiences in a wide variety of roles.

Nominated for 10 Oscars, Miss Davis was a perfectionist whose tempestuous battles for good scripts and the best production craftsmen for her films wreaked havoc in Hollywood executive suites.

”I was a legendary terror,” she once recalled. ”I was insufferably rude and ill-mannered in the cultivation of my career. I had no time for pleasantries. I said what was on my mind, and it wasn’t always printable. I have been uncompromising, peppery, intractable, monomaniacal, tactless, volatile, and ofttimes disagreeable. I suppose I’m larger than life.”

She was indeed. Few in the entertainment industry could deny that Bette Davis possessed all the legendary indestructibility of the New England Yankee that she was. Starting as a stage actress, she won spectacular fame as a screen star and, as she grew old, shifted effortlessly to high-paying television roles.

Miss Davis’s two Oscars for best performance by an actress were won in 1935, for ”Dangerous,” and in 1938, for ”Jezebel.” But perhaps she is best recalled for her tour de force as Margo Channing, the tough-talking but soft-hearted stage actress in ”All About Eve,” for which she was nominated for an Academy Award.

She made almost 100 films. Her 10 nominations for Oscars are the most any actress has received. And she received many other honors, including the Life Achievement Award of the American Film Institute and the Cesar Award of the French film industry. In 1987 she received the Kennedy Center Honors for lifetime achievements in the performing arts.

The Kennedy Honors coincided with the release of ”The Whales of August,” a film in which Miss Davis co-starred with Lillian Gish and for which she won wide critical praise. She appeared in that movie and in television and film roles despite having had a mastectomy and a series of strokes while hospitalized in 1983. ”It was my terror that I’d never work again,” she said afterwards, ”for I have always very much loved to work.”

Last April 24, Miss Davis was honored by the Film Society of Lincoln Center at its annual tribute, joining the company of such previous honorees as Sir Laurence Olivier and Charlie Chaplin. ”An honor I’m delighted to get,” she said at the time. ”Greedy, greedy. Can’t have too many awards. I’ve gotten just about every award there is.” Enduring Popularity ‘Acting Should Be Larger Than Life’

Although Miss Davis reached the apex of her popularity in films between the mid-1930’s and the early 50’s, her appeal swept across generations, due largely to her frequent appearances in made-for-television films and the repeated showings of her old, now-classic movies on television.

These classics include ”Of Human Bondage,” ”Dark Victory,” ”The Corn Is Green,” ”The Letter,” ”The Great Lie,” ”A Stolen Life,” ”Now, Voyager,” ”Mr. Skeffington,” ”The Little Foxes,” ”The Petrified Forest” and ”Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?”

New generations of entertainers, many of them female impersonators, have found her distinct mannerisms and clipped speech irresistible material for their acts.

”Oh Petah, Petah, Petah,” such an impersonator will say, rolling exaggeratedly widened eyes and puffing savagely on a cigarette. ”What a dump!” And, inevitably, the memorable line that Margo Channing utters as she walks drunkenly up the stairs at her party: ”Fasten your seat belts; it’s going to be a bumpy night.”

”You know, I’ve learned from the imitators,” Miss Davis said in an interview this year. ”I really have. I was never conscious I moved my elbow like that” – she moved it from side to side – ”until I saw someone doing me.”

She was always proud of her approach to acting. ”Natural!” she said. ”That isn’t the point of acting. The public must believe us. They must also be somehow ennobled. Did I ever try to be low-key? Never, never, never! I fought that from the beginning. I think that acting should be larger than life.” At First, Simply ‘Betty’ A Broken Home And School Away

Born Ruth Elizabeth Davis in Lowell, Mass., on April 5, 1908, Miss Davis came from a firmly rooted Yankee background. Her mother was the former Ruth Favor; her father, Harlow Morrell Davis, a Harvard Law School graduate who became a Government patent attorney.

Her father divorced her mother when Miss Davis was 7 and her sister, Barbara, was 5, leaving her mother to rear the children alone. In later years Miss Davis said many times that she saw the divorce as her father’s abandonment of his family, and that it left her barren of love for him and preternaturally devoted to her doting mother.

Mrs. Davis put the girls in boarding school in Massachusetts and moved to New York. In 1917, she was joined by her daughters.

It was at about that time that ”Betty” Davis took the more exotic-sounding name that would become world-famed. A friend of her mother’s who was reading Balzac’s ”La Cousine Bette” suggested the name-spelling change, telling her that it would ”set you apart, my dear.”

In her teens, Miss Davis returned to New England, living in several towns there while her mother worked as a portrait photographer. She waited on tables at her schools, and once, to help with family expenses, posed nude for a woman making a sculpture.

Miss Davis decided in her teens that she wanted to become an actress, and her mother took her to New York in 1928, where she arranged for her to read for Eva Le Gallienne, whose Civic Repertory Theater was then one of the most popular touring companies.

”Miss Le Gallienne thought I was not serious enough in my approach to warrant my attendance at her school,” Miss Davis recalled years later. Breaking Into the Business Stage Experience, Looks and a Voice

Miss Davis’s first professional acting job was with a winter stock company in Rochester, run by the director George Cukor, who dismissed her after a few months. She made her New York acting debut in 1929, at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village, in Virgil Geddes’s ”The Earth Between.” Brooks Atkinson, critic for The New York Times, wrote that she was ”an entrancing creature.”

Successes and disappointments were to come in rapid order after that. The young actress, then only 21 years old, was in her first Broadway hit, ”Broken Dishes,” quickly followed by ”Solid South,” in which she played the beguilingly named Alabama Follensby, the first of many Southern-belle roles that were to come her way.

The movies had learned to talk only a few years earlier, and Hollywood was greedily spiriting away Broadway actors and actresses who had good speaking voices as well as looks. It was thus perhaps inevitable that a fresh young actress with some training and experience and a couple of good notices would be asked to take a screen test.

She was given a $300-a-week contract by Universal Pictures, and Miss Davis and her mother went to Los Angeles in 1930. Her first movie role was in ”Bad Sister,” notable only for the fact that it also introduced Humphrey Bogart to films. But the movie’s cinematographer, Karl Freund, passed the word to studio bosses that ”Davis has lovely eyes,” and just as she was to be dropped, her option was picked up for another 13 weeks.

By the end of 1932, Miss Davis, discouraged after having appeared in six lackluster movies and finally without a contract, prepared to return with her mother to New York. Then she got a call from George Arliss, the highly respected English actor, who was to be her mentor until his death.

He hired Miss Davis as his leading lady in ”The Man Who Played God,” her breakthrough movie role.

The film was a success, and its producer, Warner Brothers, signed Miss Davis to her first contract. It was the start of a love-hate relationship with the studio that was characterized by Miss Davis’s frequent storming off sets, being suspended for refusing to act in what she considered inferior movies, and going to court to sever her ties with Warners.

But in her first three years at Warners Miss Davis made 14 films, including Edna Ferber’s ”So Big,” with Barbara Stanwyck starring, and ”20,000 Years in Sing Sing,” which was, she was to say, ”my only film with the great Spencer Tracy, to my everlasting regret.”

”He was the finest actor I ever worked with,” she said. Getting Parts, and Noticed Unafraid to Play The Villainess

She was working hard, in mostly forgettable fare, but Miss Davis was also learning the movie craft and earning the respect of technicians.

From the start Miss Davis, unlike leading ladies of the day, had no qualms about playing unsympathetic roles, and so was overjoyed in 1934 when she was lent by Warners to the rival RKO studios to play the cruel and slatternly waitress Mildred in W. Somerset Maughham’s ”Of Human Bondage,” opposite Leslie Howard as the crippled hero Philip.

”Every actor who becomes a star is usually remembered for one or two roles,” she said, ”like Judy Garland in ‘The Wizard of Oz’, Garbo in ‘Camille,’ Brando in ‘A Streetcar Named Desire.’ Mildred in ‘Of Human Bondage’ was such a role for me. She was the first leading-lady villainess ever played on a screen for real.”

”It’s odd that people remember me best for my evil roles,” she said, ”since I played so many other kinds of characters. But villains always have the best-written parts.”

She was widely praised for her performance as Mildred and nominated for an Academy Award, but she failed to win one, mostly, she said, because Warner Brothers did not want to promote an Oscar for a film it did not produce. She came to regard the Oscar that she won the next year, for ”Dangerous,” as ”a consolation prize.”

She was always proud of her two Oscars, though, and said this year: ”I’m not a bit modest about them. I don’t use those boys for door stops.”

Warners was treating her with new respect, giving her movies like ”The Petrified Forest,” with Leslie Howard and Humphrey Bogart, but Miss Davis harbored a festering resentment against what she called ”the contract slave system” at the studio.

Deciding in 1936 to defy the strictures of her contract, Miss Davis agreed with an English company to go to London to make two movies. Years later she was to ruefully confess that before she left, Jack L. Warner, the studio head, offered her a chance ”to play one of the great screen roles of all time, but I didn’t know it.”

” ‘Please don’t leave. I just bought a wonderful book for you,’ ” she quoted Mr. Warner as saying. ”And I said, ‘I’ll bet it’s a pip!’ and walked out of his office.” She learned later that the role she turned down was Scarlett O’Hara in ”Gone With the Wind.” Mr. Warner later gave up his option on it. The Glorious Years Memorable Roles, One After Another

In England, Miss Davis was sued by Warner Brothers, which succeeded in preventing her from working for another producer while under contract to Warners. But once she had returned to the United States, Warners gave her a new contract calling for fewer pictures at a much higher salary.

They also gave her excellent, high-budget pictures, like ”Jezebel,” for which she won her second Oscar in 1938. In a single year, 1939, Warners released no fewer than four blockbuster Davis movies: ”Dark Victory,” ”Juarez,” ”The Old Maid” and ”The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex,”

”Jezebel” began her halcyon years, she said, and ”in 1939 I secured my career and my stardom forever; I made five pictures in 12 months, and every one of them made money.”

The memorable Davis roles continued in swift order: The murderous and unfaithful planter’s wife in Maugham’s ”The Letter” in 1940, quickly followed the next year by ”The Great Lie” and ”The Little Foxes,” in which she played the scheming Regina Giddens. In 1942 she scored again in ”Now, Voyager,” as Charlotte Vale, a frumpish spinster who blossoms into a confident beauty and finds true love with Paul Henreid. The film is remembered by movie buffs for the scenes in which Mr. Henreid lights two cigarettes at once and gives one to Miss Davis.

There were other triumphs in the 1940’s – ”The Man Who Came to Dinner,” ”Watch on the Rhine,” ”Mr. Skeffington,” ”The Corn Is Green” and ”A Stolen Life.” But Miss Davis’s luck began to run out with critical and box-office disasters like ”Winter Meeting” and ”Deception,” and in 1949 Warner Brothers, after 19 years, released her from her contract while she was making the ludicrous melodrama ”Beyond the Forest.” In it a by-then plumpish Miss Davis uttered one of her most famous ”camp” lines, so often used by her mimics, ”What a dump!” Anguish and Acclaim Role of a Lifetime In ‘All About Eve’

With the end of the Warners era, Miss Davis’s third marriage, to William Grant Sherry, an artist by whom she had a daughter, Barbara Davis Sherry, was also ending. She won custody of her daughter.

Miss Davis had previously been married to Harmon Oscar Nelson Jr., a band leader, and she said in 1982 that on his insistence she had two abortions. ”That’s what he wanted,” she said. ”Being the dutiful wife, that’s what I did.” The marriage ended in divorce.

But for decades afterward, Miss Davis publicly battled with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, insisting that she had bestowed her first husband’s middle name on the Oscar. ”The Academy has fought stoically to claim that they named the Oscar,” she said. ”But of course I did. I named it after the rear end of my husband. Why? Because that’s what it looked like.”

Miss Davis’s second husband, Arthur Farnsworth, a businessman, died of head injuries suffered in a fall in 1943.

Miss Davis was filming ”Payment on Demand” in 1949 – it was not released until 1951 – when she was offered a role of a lifetime in what she was to call ”that charmed movie, ‘All About Eve.’ ” She was a last-minute replacement for Claudette Colbert, for whom the director, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, had written the role of Margo Channing, the fading Broadway star. Miss Colbert was unable to begin the film on schedule because she ”hurt her back, thank God,” as Miss Davis liked to recall it.

”When I finished reading ‘All About Eve’ I was on Cloud Nine,” said the actress. ”That night Joe Mankiewicz told me Margo Channing was the kind of dame who would treat her mink coat like a poncho.”

She played Margo that way, and brilliantly, and with the aid of a witty, literate script, sharp direction by Mr. Mankiewicz, and a sparkling cast that included Anne Baxter, Celeste Holm, George Sanders, Marilyn Monroe (in a supporting role), and Thelma Ritter, the movie became one of the all-time great Hollywood films.

During the filming of ”All About Eve,” Miss Davis became romantically involved with her leading man, Gary Merrill, and they were married in 1950. Soon afterward they adopted two children, Margot and Michael. The ‘Darkest Decade’ A Broadway Flop, A Retreat to Maine

Miss Davis received another Oscar nomination for ”The Star,” released in 1953, but the film was unsuccessful. She was by then 45 and younger actresses were being offered the parts that would have once been hers. She accepted an offer to return to Broadway in a revue, ”Two’s Company.”

When the show opened in New York in December 1952, Miss Davis recalled years later, ”The ovation was, to say the least, heartwarming, the reviews were bloodcurdling.” The revue closed after 90 performances.

Miss Davis and Mr. Merrill took an option to buy a home in Maine and, she said with wry amusement, ”We called our house Witch Way because we didn’t know which way we were going and a witch lived there. Guess who?”

”For three years I was solely a wife and mother and Gary fell out of love with me,” Miss Davis was to say years later. During that period it also became apparent that the Merrills’ adopted daughter, Margot, was retarded, and at the age of 3 she had to be put in a special school. Margot has since lived in homes for the retarded.

During what she was to call her ”darkest decade,” the 1950’s, while the the Merrills’ marriage continued to disintegrate, Miss Davis again played Elizabeth I in ”The Virgin Queen” and a year later, in 1956, appeared in Paddy Chayefsky’s ”A Catered Affair” as Ma Hurley, a Bronx housewife, which she sometimes said was her favorite role. The Merrills also traveled cross-country doing one-night stands in ”The World of Carl Sandburg” until 1960, when they were divorced. Friends and Enemies Fonda, Crawford, Cagney and Flynn

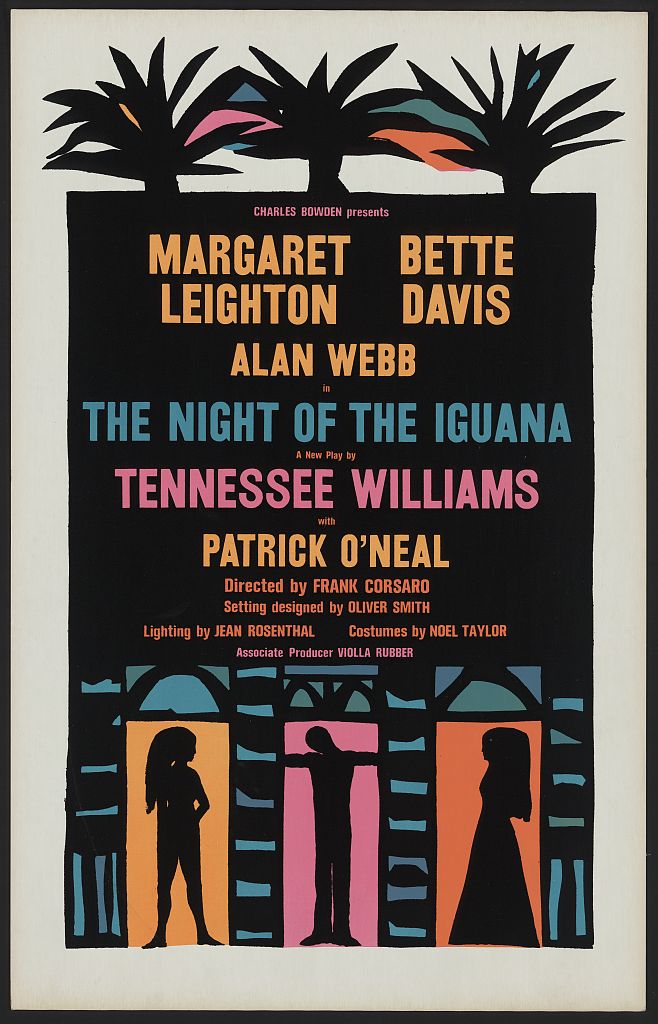

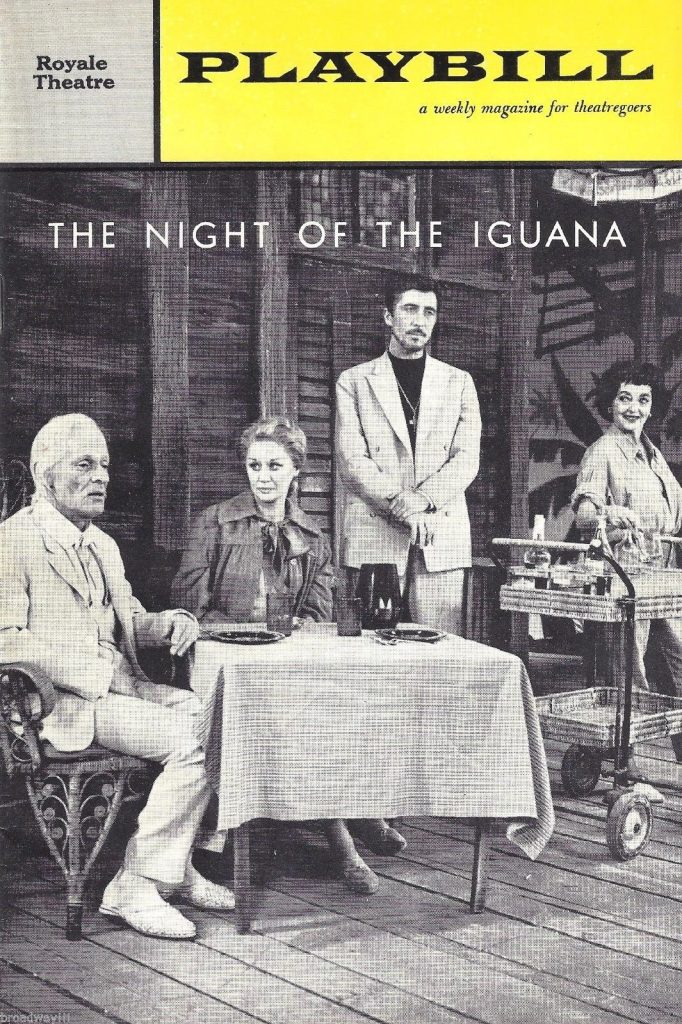

Having settled into character acting, Miss Davis in 1961 scored a success as the gin-soaked ”bag lady” Apple Annie in ”Pocketful of Miracles.” That same year she was praised for her performance on Broadway in Tennessee Wiliams’s ”The Night of the Iguana,” which she left in April 1962 to film ”Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?” a box-office winner that earned her yet another Accademy Award nomination for best actress of the year.

The horror movie, in which Miss Davis wore pasty white makeup and padded herself to appear overweight, revolved around two show-business has-been sisters living in creepy seclusion in a Hollywood mansion. The role of the loony Baby Jane Hansen, addled into thinking she was going to make a comeback in vaudeville, gave Miss Davis a chance to pull out all the acting stops, and she did so with relish. The other, wheelchair-bound, sister was played by Joan Crawford.

The casting of Miss Davis and Miss Crawford in ”Baby Jane” resuscitated longstanding rumors that they had feuded when both were Warners stars. In 1982 Miss Davis told an interviewer, ”I never feuded with Joan Crawford. During ‘Baby Jane’ the whole world hoped we would fight but we did not. We were both pros.” In any event, Miss Davis was not reticent about revealing her rancor against other performers. She accused Miriam Hopkins, with whom she co-starred in ”The Old Maid” and ”Old Acquaintance,” of upstaging her and scene-stealing. She also disliked Errol Flynn, her co-star in ”Elizabeth and Essex,” calling him ”unprofessional.”

Intense as her rivalries were, her friendships were deep and long lasting, particularly for Claude Rains, Henry Fonda, James Cagney, Paul Henreid, Olivia de Havilland, Anne Baxter and Geradine Fitzgerald.

As she grew older, Miss Davis continued making movies, many of them horror thrillers or melodramas, like ”The Anniversary” (1968), in which she wore a patch over one eye.

Unlike many of her contemporaries who held out against appearing on television when it was in its infancy in the 1950’s, Miss Davis embraced it. She appeared as a guest on the Jimmy Durante comedy show, and made episodes of popular series like ”Gunsmoke” and ”Perry Mason.” Writing Her Own Epitaph ‘The Sweetness Of My Joy’

Despite advancing age Miss Davis kept on working, appearing on television and in an occasional movie, some of them made for television. She said she worked into her later years because the money came in handy, and work was part of her Yankee heritage. ”It is only work that truly satisfies,” she said. ”No one has ever understood the sweetness of my joy at the end of a good day’s work. I guess I threw everything else down the drain.”

This included her personal life, she said, adding: ”All my marriages were charades, and I was equally responsible. But I always fell in love. That was the original sin.”

It was never a secret that Miss Davis was temperamental, opinionated and often difficult to get along with, but in 1985 a scandalous book about her, by her own daughter, shocked her critics as well as her fans.

In ”My Mother’s Keeper,” B. D. Hyman portrayed Miss Davis as an abusive, domineering and hateful mother and as a grotesque alcoholic who was largely responsible for her own mistreatment by certain of her husbands. Two years later Miss Davis replied to Mrs. Hyman’s charges with her own bestseller, ‘This ‘N That,” in which she defended herself as the victim of a lying and ungrateful child. She confessed later that her estrangement from her daughter pained her.

For some years after her last divorce Miss Davis lived in Weston, Conn., but in the late 1970’s she moved into an apartment in West Hollywood.

”Indestructible,” she once said. ”That’s the word that’s often used to describe me. I suppose it means that I just overcame everything. But without things to overcome, you don’t become much of a person, do you?”

”I know what I want as my epitaph,” she said. ”Here lies Ruth Elizabeth Davis – she did it the hard way

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.