The main thing, of course, was the music; no popular singer has sung so many first-rate songs, old and new. He brought to this material a unique, evocative phrasing that personalised the romantic sentiments in the lyrics. The disc jockey William B. Williams once said, “Sinatra’s records were on the radio during more deflowerments than those of any other singer’s.”

Sinatra developed his style by studying many performers, but it was of Mabel Mercer that he said, “She taught me everything I know.” In the 1940s he haunted Tony’s West Side, an intimate bar-restaurant on 52nd Street in New York, to hear the Staffordshire-born Mercer sing superior, neglected songs with impeccable diction and an innate sense of story-telling.

You can hear her influence in Sinatra’s 1957 recording of David Raksin and Johnny Mercer’s “Laura”. Most vocalists singing “The laugh that floats on a summer night / That you can never quite recall” would sensibly take a breath after “recall”, thereby starting the new thought “And you’ll see Laura on the train that is passing through” with the new breath. But Sinatra manages to maintain the sense despite taking his breath after “never quite”. Then, in a smooth, flowing phrase, he holds “Recall” (which he sings full-out), continuing into a tender “And you’ll see . . .”

Here he takes his next breath to sing the word “Laura”, which Raskin composed to be sung on two repeated notes. Sinatra, however, abandons the second note and swoops to a lower one (staying, of course, within the harmony), thus giving the effect of caressing the name, as well as providing a strand of melodic invention which the conductor/arranger Gordon Jenkins can’t resist echoing in the strings. The song ends with one of Johnny Mercer’s surprise twists: “That was Laura, but she’s only a dream.” To emphasise this twist, Sinatra sings full-out on the word “but” (placed on the highest note in the song), and then brings an aching sadness to the last line, he and the orchestra pausing dramatically between “She’s only” and “a dream”.

On an earlier recording of Cole Porter’s “Night and Day”, Sinatra made an identical downward swoop on the word “Torment” (also composed to be sung on two repeated notes), probably motivated by the same sense of emotion. Such improvisation, plus even more annoying liberties with many of his rhymes – “I said to myself, `This affair never will go so well’, / But why should I try to resist when baby, I know damn [should be “so”] well” – eventually prompted a telegram from Porter, asking, “Why do you sing my songs if you don’t like the way they were written?”

Throughout his career Sinatra attracted controversy, over his private life, his political views and, most obviously, his friendship with Mafia figures. For over 40 years stories circulated about his links to the Mafia. Recently, while sitting between two women in a Los Angeles restaurant, he leant back too far in his chair and found himself falling. He caught hold of the two women, who tried to save themselves by catching hold of the tablecloth, after which all three fell to the floor, followed by the contents of their table. So closely was Sinatra identified with organised crime that everyone who saw him lying there immediately assumed he had finally been the victim of a Mob killing and ran from the restaurant in terror.

His parents were both Italian immigrants. His father, a fireman who also boxed briefly under the name Marty O’Brien, was shocked by his son’s early decision to sing for a living. Francis’s mother, Natalie Della (Dolly), a mid-wife, abortionist, tavern owner and political activist, was more sanguine when, at the age of 16 and full of high pie-in-the sky hopes he dropped out of high school, in Hoboken, New Jersey, unable to wait until graduation to become a singing star. He performed at dances, weddings, and other New Jersey functions until 1935, when he and three fellow Hobokenites auditioned for the radio series Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour. Bowes liked them, dubbed them the Hoboken Four, and put them on his show. They won first prize and a spot in one of the Major’s vaudeville tours.

Sinatra gained invaluable experience during his two years at the Rustic Cabin, a New Jersey roadhouse where he worked as singing head waiter and master of ceremonies, putting up with the low pay because the place featured regular radio broadcasts. He also sang, free of charge, on the New York independent radio station WNEW.

In 1939 Harry James, who had just left the Benny Goodman band to start his own outfit and had yet to find a vocalist, heard Sinatra on WNEW and dropped into the Cabin the following night. He hired him at $65 a week, despite the singer’s adamant refusal to change his name. Soon the trade paper Metronome, reviewing the new band, praised “the pleasing vocals of Frank Sinatra, whose easy phrasing is especially commendable”.

He had been with James for six months and was still under contract to him when a CBS executive tipped off Tommy Dorsey about “the skinny kid who’s singing with Harry’s band”, after which Dorsey auditioned him and offered $125 a week. James, knowing Sinatra’s wife Nancy was pregnant and that the extra dollars would come in handy, released him from his contract with a grin and a handshake.

The skinny kid’s original inspiration was Bing Crosby, particularly for the way he handled a microphone. “The microphone is the singer’s basic instrument,” Sinatra maintained. “You have to learn to play it like it was a saxophone.” Or a trombone; it is part of musical mythology that “The Voice” learnt his breath control by studying Dorsey’s trombone technique night after night. In 1941, the readers of Billboard voted him the year’s “Outstanding Male Vocalist”. In 1942 Metronome accorded him the same honour.

He sang with Dorsey for nearly three years, made 83 recordings (including the very popular “This Love of Mine” and “I’ll Never Smile Again”), and gained useful camera experience when the band appeared in the films Las Vegas Nights (1941) and Ship Ahoy (1942). In 1942, when Sinatra left to go out on his own, Dorsey, the womanising, vindictive, hard-drinking brawler who was incongruously billed as “The Sentimental Gentleman of Swing”, demanded 431/3 per cent of the ingrate’s earnings for the next 10 years.

The date 30 December 1942 marked the the end of the Band Era and the start of the Age of the Crooner. On that day Sinatra appeared as an “Extra Added Attraction” at the New York movie house the Paramount, on a bill headed by Benny Goodman and his band. The teenaged bobby-soxers in the audience gave Sinatra a screaming, swooning, headline-making reception, and he was suddenly the hottest talent in show business. During one engagement, when he missed a few performances because of a sore throat, hundreds of teenage girls marched forlornly around the theatre, mourning their idol’s non-appearance by wearing black bobbysocks.

In 1942 Sinatra had been chatting with a friend and fellow singer named Barry Wood. “You’re really going places, Frank,” Wood said. “What are your future plans?” Sinatra replied, “I want to be the star of the Hit Parade radio show.” Wood was lost for words as he was then the star of The Hit Parade. Sinatra took over the following year. He also signed a contract with RKO, who cast him as a swooner-crooner named Frank Sinatra in a loose adaptation of the Broadway musical Higher and Higher (1943).

RKO used Rodgers and Hart’s “Disgustingly Rich”, but jettisoned the rest of their songs, including “It Never Entered My Mind”, which Sinatra would record, memorably, 12 years later. The film’s new score, by Harold Adamson and Jimmy McHugh, provided the singer with two recording hits, “A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening” and “I Couldn’t Sleep a Wink Last Night”.

RKO’s next assignment, Step Lively (1944) was even thinner than Frankie Boy himself; a feeble re-hash of the old Marx Brothers flop Room Service (1938), but it had a lively score by Sammy Cahn and Jule Styne. When MGM bought up his RKO contract, Sinatra insisted that Cahn and Styne write the score for his first Metro film, the hugely successful Anchors Aweigh (1945). That year he also won a special Academy Award for his appearance in The House I Live In, a10-minute short attacking racial and religious prejudice.

Sinatra’s emaciated frame and hollow cheeks made him God’s gift to gagwriters. A 1945 Bob Hope radio show featured a sea sketch in which First Mate Jerry Colonna shouted, “Cap’n, look at the flag that ship’s flying! A skull and crossbones!” Hope snapped back, “Everywhere you go – Sinatra!” And he was everywhere: in supper clubs, on records, on the cinema screen, on radio in The Hit Parade, in his own radio show Songs by Sinatra and as Guest Star on just about everyone else’s. When Bing Crosby said, “A singer like Frank only comes along once in a lifetime . . . but why did it have to be my lifetime?” one suspects he was only half joking.

In 1947 Sinatra inspired some very unwelcome headlines after a Cuban holiday, during which he was seen all over Havana in the company of the deported Mafia killer and vice king Charlie “Lucky” Luciano. A few months later, his performance in It Happened in Brooklyn (1947) was mocked by the Hearst columnist Lee Mortimer, who referred to him as “Frank (`Lucky’) Sinatra”. Soon afterwards, there were even more unwelcome headlines when the singer (with the help of four friends) attacked Mortimer outside a Hollywood night-club and put him in hospital. He had to pay damages.

In the 1960s, when Sinatra sang “It Was a Very Good Year” he was certainly not referring to 1948; that was the year of more public brawls and attacks from the Hearst press, not to mention The Kissing Bandit, a film so dire that he took public swipes at it for the rest of his life. In a desperate attempt to try something new and different on the screen, he persuaded MGM to lend him back to RKO for the straight role of a priest in an even worse film, The Miracle of the Bells (1948). One critic said the movie proved there should be a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to God.

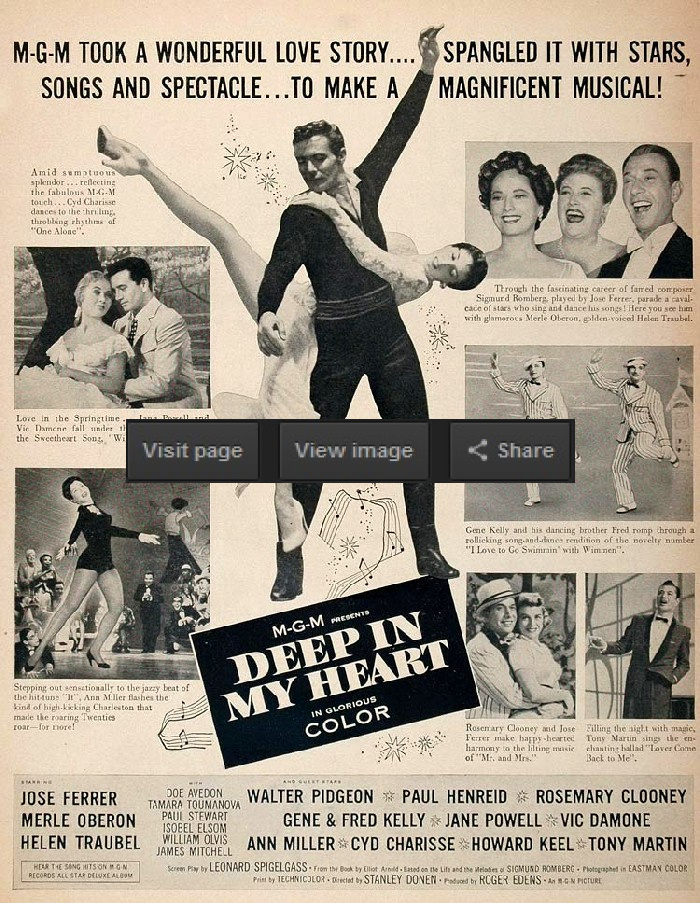

Things looked up in 1949, when Sinatra was reunited with his Anchors Aweigh co-star Gene Kelly for the sprightly Take Me Out to the Ball Game and the joyously innovative On the Town, but in 1950 the news that he had left Nancy and their three children to marry Ava Gardner caused a torrent of bad press and the disbanding of most of his fan clubs.

In his heyday Sinatra never employed the hoary publicity stunt of insuring his voice for a vast sum, and must have regretted this in the early 1950s; heavy drinking and smoking had wreaked havoc with his vocal cords, which began haemorrhaging. Everything was turning sour; both MGM and The Hit Parade had dropped him, his records couldn’t be given away, and he owed a fortune in back taxes.

After Ava Gardner interceded with her former boyfriend Howard Hughes, now head of RKO, Sinatra was cast in a little comedy-with- music called It’s Only Money. When the film was finally released in 1951, he was billed below Jane Russell and Groucho Marx, and the title had been changed to Double Dynamite, in honour of Russell’s frontage, which was deemed more commercial than Frank Sinatra. A Down Beat poll of male vocalists in November 1951 showed that he had slid down to fourth place, below Billy Eckstine, Perry Como and Frankie Laine. By 1952 “The Voice” was washed up. Although he gave a splendid, assured performance in Universal’s Meet Danny Wilson (1952), and was in excellent voice, few people bothered to see the movie.

He fought his way back to centre stage by begging Columbia’s Harry Cohn for the role of the feisty Private Angelo Maggio in the film version of the James Jones novel From Here to Eternity (1953), which he played for a Woolworth price. His performance earned him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and Variety hailed his comeback as “the greatest in showbiz history”.

In 1954, six months after the expiration of his Columbia Records contract, Sinatra signed with a reluctant Capitol, and made a return to the record business that was even more triumphant than his film comeback. In a decade when novelty hits like Perry Como’s “Hot Diggity”, Georgia Gibbs’s “Tweedle Dee” and Patti Page’s “Doggie in the Window” were million-sellers, his Capitol albums offered fine standards by George and Ira Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer, Rodgers and Hart, Lerner and Loewe, Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Kern, Kurt Weill and Noel Coward, plus custom- made new songs like “Come Fly With Me”, “It’s Nice to Go Trav’lling” and “The September of My Years”, by his personal songwriters, Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen, a team he put together.

Swing Easy, In the Wee Small Hours, Songs for Swingin’ Lovers, Close to You, A Swingin’ Affair, Come Fly With Me, Only the Lonely and the rest of his Capitol albums kept up a remarkable standard. Most were made with his all-time favourite conductor/ arranger, the late Nelson Riddle. “Nelson had a fresh approach to orchestration,” Sinatra said, “and I made myself fit into what he was doing.”

Sinatra’s film comeback continued in Young at Heart (1954), with Doris Day. In Stanley Kramer’s medical saga Not as a Stranger (1955), his co- star was Robert Mitchum, who once admitted, “The only man in town I’d be afraid to fight is Frank. I might knock him down, but he’d keep getting up until one of us was dead.” Also in 1955 he surpassed his Eternity performance as the tormented junkie Frankie Machine in The Man with the Golden Arm, then had a light comedy success (complete with Cahn/ Van Heusen hit song) in The Tender Trap.

The same year saw the making of Guys and Dolls, which Sinatra found a miserable experience. He knew he was miscast in the supporting role of Nathan Detroit, and hankered after Sky Masterson, the star part Marlon Brando was playing. (The previous year, Brando had beaten him to the role of Terry Malloy, the ex-prize fighter who “could have been a contender” in On the Waterfront, a story set in Sinatra’s hometown, Hoboken.) And he hated acting with Brando, who would require take after take, whereas repetition maddened “One-Take Frankie”; he walked off the film Carousel (1956) on the very first day when he learnt he would have to play every scene twice – once for CinemaScope and once for Todd-AO.

Yet he took infinite pains in his spiritual home, the recording studio; his recording of “Day In, Day Out” required 31 takes before he was satisfied. An even greater dedication went into Peggy Lee’s The Man I Love album. Sinatra produced it, conducted it, chose the songs, hired Riddle to write the arrangements, designed the cover, and, with his own hands, put menthol in Lee’s eyes to make them look suitably misty for the cover photograph.

In the 1960s he left Capitol and started his own Reprise record label, turning out another series of magnificent albums with Riddle, Johnny Mandel, Sy Oliver, Billy May, Quincy Jones, Neal Hefti, Gordon Jenkins, Don Costa, Claus Ogerman, and his regular arranger-conductor of the 1940s, Axel Stordahl.

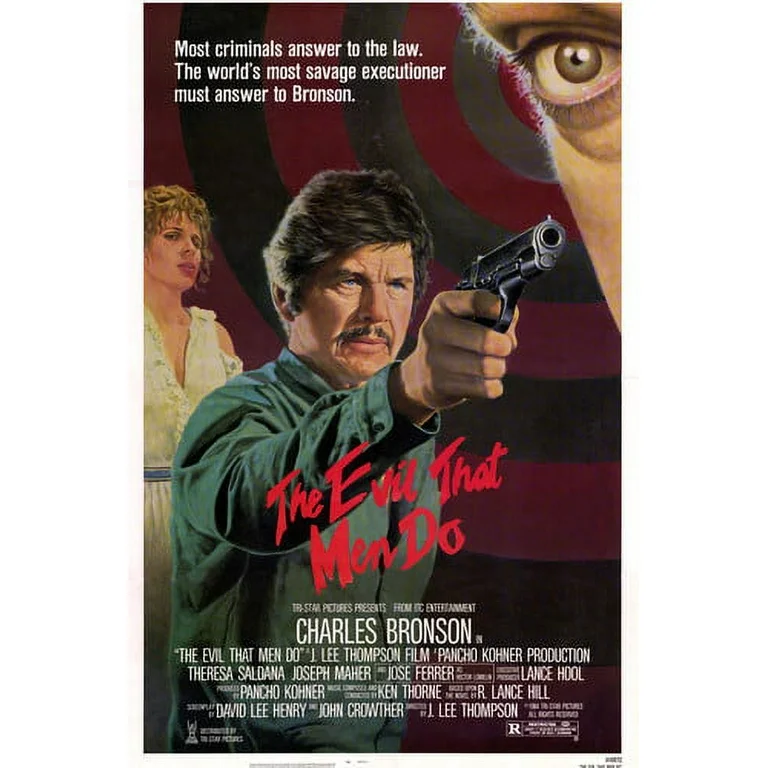

The 40-odd films Sinatra made after his 1953 comeback also included High Society (1956), The Joker is Wild (1957), Pal Joey (1957), and The Pride and The Passion (1957), in which he was ludicrously miscast as a Spanish peasant. Rumour had it that he only accepted the role because the film was made in Spain, where his estranged wife Ava Gardner was now living; still madly in love with her he hoped to dissuade her from ending their marriage, but she wouldn’t be swayed and divorced him that same year.

In 1962 he made the brilliant, eerily prophetic assassination thriller The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Sinatra, devastated by the assassination, the following year, in 1963, of his friend John F. Kennedy, blocked the film’s re-release for decades.

A lifelong Democrat, the singer astonished his intimates in the 1970s by suddenly becoming an ardent Republican. “It was bad enough when Frank palled around with `Lucky’ Luciano and `Bugsy’ Siegel,” said a screenwriter friend. “Now he’s buddies with Nixon, Agnew and Reagan!”

In 1971 Sinatra, brooding about badly received films like Dirty Dingus Magee (1970), a decline in album sales and the recent failure of his brief marriage to Mia Farrow, announced his retirement. The final song of his “farewell performance” at the 50th Anniversary benefit show for the Motion Picture and Television Relief Fund was “Angel Eyes”, which ends: “Pardon me, but I gotta run. / The fact’s uncommonly clear, / Gotta find who’s now number one, / And why my angel eyes ain’t here. / ‘s’cuse me while I disappear.”

The disappearance only lasted 24 months; he announced his “unretirement” with Ol’ Blue Eyes is Back, 1973’s most expensive television special, and with an LP of the same name which reached the top 15. Three years later he married Barbara Marx, the divorced wife of Zeppo, the youngest Marx brother. When the judge who performed the civil ceremony asked the bride, “Do you take this man for richer, for poorer?”, the happy groom ad-libbed, “Richer, richer!”

In the last decades of his life, the nickname “Ol’ Blue Eyes” was more appropriate than “The Voice” but, although his vocal range was diminished, his phrasing was as impeccable as ever. You could still hear a pin drop whenever he sang the Mercer/Arlen classic “One For My Baby”, a song that didn’t belong in the same repertoire as “My Way”, the self-aggrandising paean he was singing just before his collapse on 6 March 1994, during a concert in Richmond, Virginia. Rushed to hospital, he was asked by anxious doctors to stay overnight, but, true to form, waved away such a suggestion and boarded his private jet for home. His reactions were equally characteristic earlier in the same week when he was given a “Living Legend” award at the 1994 Grammys; first he wept at the audience’s standing ovation, then complained that he hadn’t been asked to sing at the ceremony. His first Duets album, made the preceding year, pleased him by reaching Second Place in Billboard’s album charts but it was a clumsy and pointless endeavour, as was Duets II, released in late 1994.

Sinatra had come close to death 30 years before while starring in None But the Brave (1964), a movie he also produced and directed. It was filmed on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, where he nearly drowned. While swimming, he and Ruth Koch, his executive producer’s wife, were engulfed by a giant wave and pulled out to sea by the undertow. When the burly actor Brad Dexter swam to the rescue, an exhausted Sinatra gasped “Save Ruth – I’m going to die.”

Somehow Dexter managed to keep both swimmers afloat until a surfboard crew arrived. He told Sinatra’s biographer Earl Wilson: “I felt Frank meant it when he said I should save Mrs Koch and not worry about him. I felt that he wouldn’t care if he died. Because he’d lived a great life. Frank had been there and back.”

Francis Albert Sinatra, singer and actor: born Hoboken, New Jersey 12 December 1915; married 1939 Nancy Barbato (one son, two daughters; marriage dissolved 1950), 1951 Ava Gardner (marriage dissolved 1957), 1966 Mia Farrow (marriage dissolved 1968), 1976 Barbara Marx (nee Blakely); died Los Angeles 15 May 1998.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.