IMDB entry:

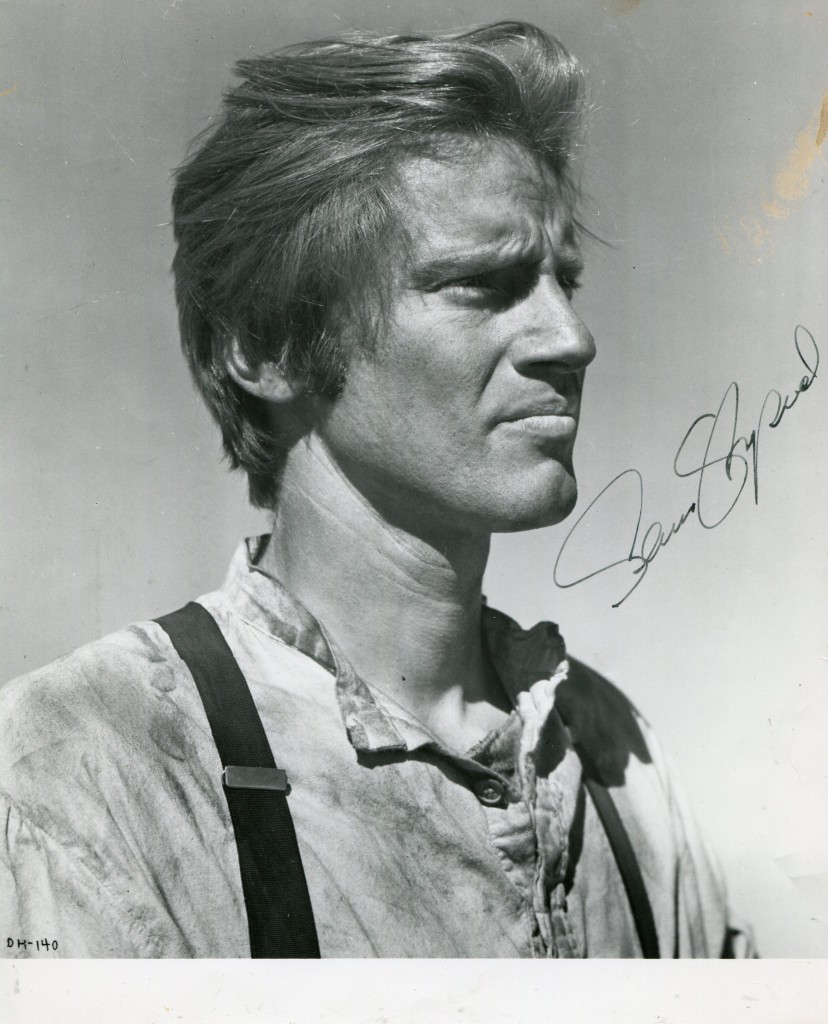

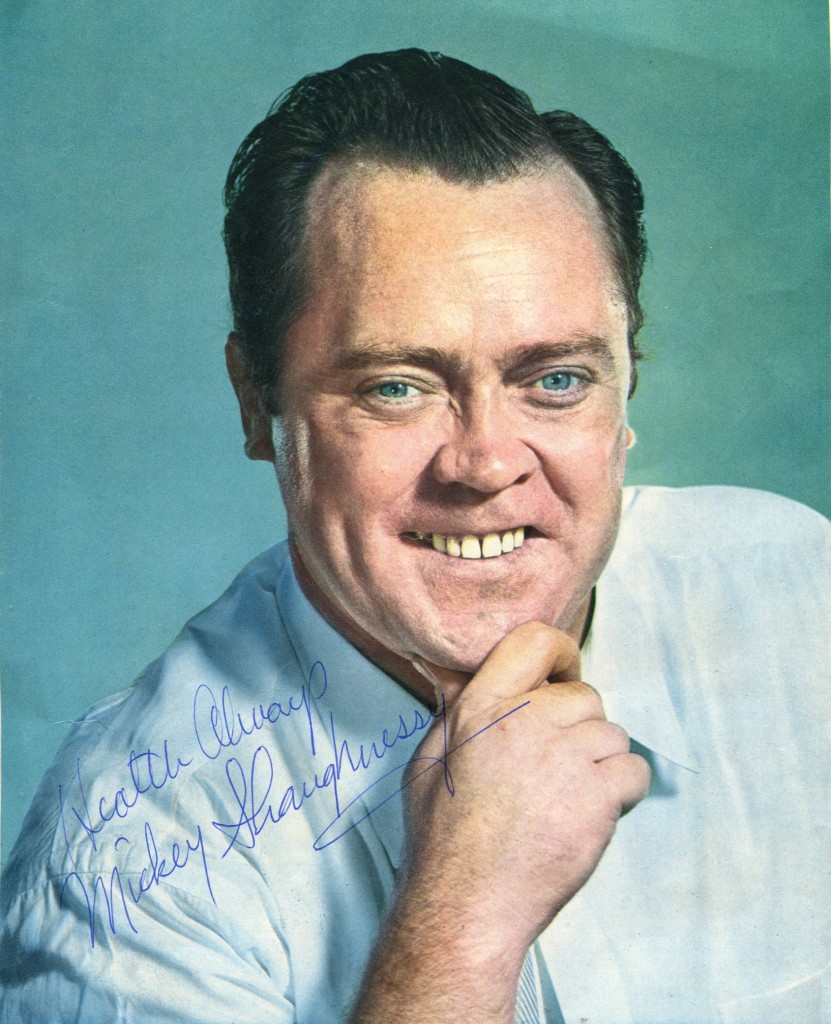

Mickey Shaugnessy, the Irish-American character actor best known for his portrayal of Elvis Presley’s musical mentor in the rock n’ roll classic “Jailhouse Rock” (1957), was born Joseph Michael Shaughnessy on August 5, 1920 in New York City. As a performer, the young Mickey made his bones on the Catskill Mountains tourist resort circuit.

During a stint in the Army during World War II, Mickey appeared in a service revue. After being demobilized, he made his living making the rounds of the nightclub circuit with a comedy act. His breakthrough as an actor came with his debut in support of the legendary Judy Holliday and great meat n’ potatoes character actor Aldo Ray in George Cukor‘s The Marrying Kind (1952).

Shaughnessy signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which typecast him as dumb but likable lugs in such pictures as Vincente Minnelli‘s Designing Woman (1957). He was memorable as “the Duke” in ‘Michael Curtiz”s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) for MGM and even acted Jerry Lewis off of the silver screen as Jerry’s wrassler-pal inDon’t Give Up the Ship (1959). Other major pictures he appeared in were Fred Zinnemann‘s Academy Award-winning From Here to Eternity (1953), Robert Wise‘s Until They Sail (1957) in support of up-and-coming Paul Newman, Frank Capra‘s disappointing final film Pocketful of Miracles (1961), and Henry Hathaway‘s comedic potboiler North to Alaska (1960) with John Wayne.

In 1960 alone, the Mick appeared in two exploitation classics for Albert Zugsmith, “College Confidential” with professional marrieds Steve Allen and Jayne Meadows, andSex Kittens Go to College (1960) with a young Tuesday Weld. In “The Clown,” Mickey had the honor of playing a mute clown who avenges the honor of another young lovely,Yvette Mimieux, in an episode during the second season of the classic TV chiller series, “One Step Beyond.”

In the early ’60s, Mickey revived his nightclub act, which was always a “clean” act, even into the 1980s, despite his success as the foul-mouthed sailor whose obscenities were beeped-out on the soundtrack of “Don’t Go Near the Water (1955). In 1965, Mickey had the dubious honor of appearing as Jack Mulligan in “Kelly,” an original Broadway musical about a Tammany Hall-like Irish gang set in the 1880s that starred Wilfrid Brambell as the eponymous Dan Kelly and Maytag repairman extraordinaire Jesse White as “Stickpin” Sidney Crane. Produced by David Susskind and Daniel Melnick in association with Joseph E. Levine, directed and choreographed by future Academy Award nominee Herbert Ross, and boasting music by Moose Charlap and a book and lyrics by Eddie Lawrence, “Kelly” opened and closed on February 6th, 1965, after all of one one performance. Mickey never performed on the Great White Way again.

In all, Mickey starred in almost two score movies and a score of TV shows before winding up the bulk of his career in the early ’70s with a role in the short-lived TV series “The Chicago Teddybears” (1971) in support of Dean Jones and John Banner. Despite many memorable performances, he will best be remembered as the imprisoned con Hunk Houghton in “Jailhouse Rock.” Mickey’s con befriends Elvis, in his best-starring vehicle, as a young man thrown into the pokey for killing another man to defend a woman’s honor. It is Mickey’s Hunk who has the insight and wisdom to realize that Elvis is a natural and should perform in the upcoming prison show.

Wowing the incarcerated crowd like the Man in Black Johnny Cash would a decade later at Folsom, Elvis finds his true calling and becomes a pop star after vamoosing the hoosegow. With true love Judy Tyler, the once and future King establishes a record company to flog his hot wax, but success spoils him, and soon Elvis decides to ditch his best gal and their company to sign with some slick Hollywood recording industry types. Former best pal-from-the-slammer Mickey shows up and bangs some sense into Elvis’ vaselined head, but unfortunately, the blow to The King’s noggin damages his vocal chords. No longer able to sing, Elvis is given up on by the slick Hollywood boys and all those who had been exploiting him.

Hollywood in that era, and particularly MGM, were nothing if not dutifully didactic, and a humbled Elvis learns the true meaning of love, friendship and fidelity when Miss Tyler and the Hunk stick out the bad times with him. In true Hollywood fashion, The King’s voice is miraculously restored and he once again storms the charts. A landmark in the rock n’ roll film with almost as much impact as “A Hard Day’s Night” (1964) had on a later generation, Jailhouse Rock (1957) was added to the Library of Congress’ Film Registry in 2004.

Sadly, Mickey Shaughnessy would not live to see that honor, nor the release of his final film. He died from lung cancer just two weeks shy of his 65th birthday on July 23, 1985.