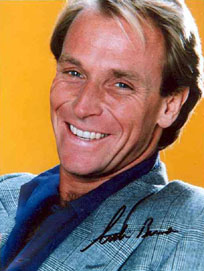

Rugged, hirsutely handsome Corbin Bernsen blazed to TV stardom in 1986 on L.A. Law(1986) as opportunistic divorce lawyer “Arnie Becker”, whose blond and brash good looks, impish grin and aggressive courting style proved a wild sex magnet to not only the beautiful female clients desirous of his “services”, but his own lovelorn secretary who frequently bailed him out of trouble. Bernsen invested the Becker character with a likable “bad boy” charm that made him a favorite among the tight ensemble for eight solid seasons. In the process, he earned multiple Emmy and Golden Globe nominations. He also proved the role was no flash-in-the-pan or dead-end stereotype, maintaining a steady career over the course of three decades now with no signs of let up. Moreover, his deep love for acting and intent devotion to his career recently impelled him to climb into the producer/director’s chair.

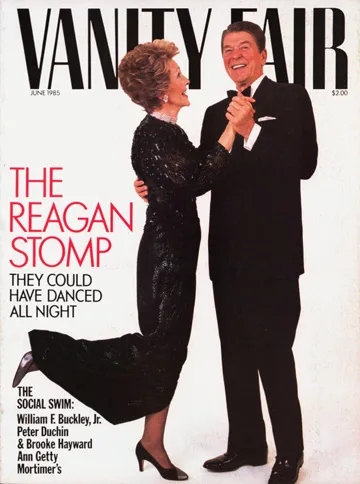

Born in North Hollywood, California, on September 7, 1954, Corbin was raised around the glitz of the entertainment business. The eldest of three children born to 70s film/TV producer Harry Bernsen and veteran grande dame soap star Jeanne Cooper (the couple divorced in 1977), he graduated from Beverly Hills High School and attended UCLA with the intention of pursuing law. Instead, he went on to receive a BFA in Theatre Arts and MFA in Playwriting. He worked on the Equity-waiver L.A. stage circuit as both actor and set designer, making his film debut as a bit player in his father’s picture Three the Hard Way (1974). Appearing unobtrusively in a couple of other films, he set his sights on New York in the late 70s. During his salad days, he eeked out a living as a carpenter and roofer while sidelining as a model. His first big break came in 1983 with the role of “Ken Graham” on daytime’s Ryan’s Hope (1975). During this time, he also met and married TV costumer designer Brenda Cooper, who later worked on The Nanny (1993) sitcom. They divorced four years later. This break led to an exclusive deal by NBC and eventually the TV role of a lifetime. The perks of his newly-found stardom on L.A. Law (1986) included a hosting stint on Saturday Night Live (1975) and the covers of numerous major magazines. Wasting no time, he parlayed his sudden small screen success into a major movie career, usually playing charmingly unsympathetic characters. He co-starred asShelley Long‘s egotistical husband in the lightweight reincarnation comedy Hello Again(1987); played an equally vain Hollywood star in the musical comedy Bert Rigby, You’re a Fool (1989); and starred as a disorganized ringleader of a band of crooks in the bank caper Disorganized Crime (1989). He capped the 1980s decade opposite Charlie Sheenand Tom Berenger in the box office hit Major League (1989), which took advantage of his natural athleticism, playing ballplayer-cum-owner “Roger Dorn”. Two sequels followed.

Corbin’s career has merrily rolled along ever since – active in lowbudgets as well as pricier film fare portraying both anti-heroes and villains. On the TV homefront, he has appeared in a slew of mini-movie vehicles, including Line of Fire: The Morris Dees Story(1991) as the famed civil rights attorney, and has ventured on in an assortment film genres – the mystery thriller Shattered (1991), which re-teamed him with Tom Berenger; the romantic comedy Frozen Assets (1992), again with Shelley Long; the war horror taleGrey Knight (1993); the slapstick farce Radioland Murders (1994); the melodramatic An American Affair (1997), and the fantasy adventure Beings (2002). Topping it off, Corbin’s title role in the expert thriller The Dentist (1996) had audiences excogitating a similar paranoia of tooth doctors as Anthony Perkins had decades before with motel clerks. As spurned husband-turned-crazed ivory hunter “Dr. Alan Feinstone”, Corbin reached cult horror status. The movie spawned a sequel in which he also served as associate producer.

Into the millennium, Corbin returned to his daytime roots with a recurring role on motherJeanne Cooper‘s popular serial The Young and the Restless (1973), and is currently seen as “John Durant” on General Hospital (1963), a role he’s played since 2004. A game and excitable player on reality shows, he added immeasurable fun to the “Celebrity Mole” series, and has enjoyed recurring roles on the more current and trendy The West Wing(1999), JAG (1995), Cuts (2005) and Psych (2006).

Of late, Corbin has decided to tackle the business end of show biz. In 2004, he formed Public Media Works, a film/TV production company in order to exert more creative control over his projects. On top of the list is the loopy film comedy Carpool Guy (2005), which he directed, produced and co-starred in. It features more than 10 of the currently reigning soap opera stars, including a wildly eccentric Anthony Geary in the title role, and, of course, his irrepressible real-life mom, Jeanne Cooper.

Obviously, his errant on-camera antics does not reflect a similar personal lifestyle for Corbin as he has been happily married (since 1988) to lovely British actress Amanda Pays. They have appeared together in the sci-fi film Spacejacked (1997) and the TV-movies Dead on the Money (1991) and The Santa Trap (2002), among others. The couple have four children, including twin boys. Just a few years ago, they relocated to Los Angeles after living in England for some time. In between, he still shows off as a master carpenter at home and continues to dabble in writing. Perseverance and dedication has played a large part in the acting success of Corbin Bernsen. Gleaning a savvy, take-charge approach hasn’t hurt either — characteristics worthy of many of the sharpies he’s played on screen.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

Corbin Bernsen stars as Henry Spencer in the sixth season of the USA Network original series PSYCH, also starring James Roday and Dule Hill.

Bernsen is also forging ahead as a prolific writer, producer and director, creating films for his Home Theater Films production and distribution banner.

As an actor, Bernsen recently completed a role as actress Rebecca Hall’s father in the indie comedy Lay The Favorite starring Bruce Willis, Vince Vaughn and Catherine Zeta Jones, directed by Stephen Frears. He also appears in the comedy The Big Year, directed by David Frankel for Fox 2000, starring Owen Wilson, Jack Black and Steve Martin.

For his Home Theater Films distribution banner, Bernsen recently completed writing, producing, directing and starring in the All-American Soap Box Derby film, 25 Hill which also stars Nathan Gamble (Dolphin Tale), Rolonda Watts (Days of Our Lives), Bailee Madison (Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark), Tim Omundson (Psych, Mission Impossible III), Maureen Flannigan (7th Heaven, A Day Without A Mexican), Ralph Waite (The Bodyguard), Meg Foster (They Live) and Michael Tucker (LA Law, D2: The Mighty Ducks) which he shot on location in Akron, Ohio.

Bernsen also just completed starring, writing and directing Barlowe Mann, an inspirational family drama. The film is a co-production between Home Theater Films and the small town of Provost, Alberta, Canada (Population: 2000) which helped finance the film, which stars Bernsen, Nathan Gamble (Dolphin Tale, Batman Returns), Dendrie Taylor (The Fighter ) and Bruce Davison (X-Men).

Previously, Bernsen starred in, wrote, produced and directed the drama Rust, for his production company in which Bernsen plays a minister who returns to his hometown to make sense of the aftermath of a local tragedy. The film, shot in the small town of Kipling, Canada, was released by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment in October 2010. Bernsen earned his Master’s in Playwriting from UCLA’s Theater Arts Department, later receiving a Drama-Logue Award for his scenic design of the Pilot Theater production of American Buffalo. After moving to New York and appearing in the off-Broadway production of Lone Star and a touring company of Plaza Suite, he became a regular for two years on the daytime drama Ryan’s Hope.

Roles in Blake Edwards’ S.O.B., King Kong and Eat My Dust, in addition to guest starring credits on a number of episodic mainstays, prompted an exclusive deal with NBC, which led to his role as Arnie Becker, the shrewd and handsome divorce attorney on the long-running L.A. Law series.

L.A. Law catapulted Bernsen to overnight stardom. During the late 80’s and early 90’s, he appeared on over 50 magazine covers and earned both Emmy and Golden Globe nominations, hosted Saturday Night Live, and appeared on Seinfeld and The Larry Sanders Show. In the feature film arena, he starred in the motion picture comedy Hello Again, followed by other critically acclaimed roles in Disorganized Crime, Wolfgang Peterson’s Shattered, and as Cleveland Indians third baseman-turned-owner Roger Dorn in the extremely popular Major League series of films. Other film credits include Tales From the Hood and Great White Hype and he starred opposite Robert Downey Jr. and Val Kilmer in the Warner Brothers feature Kiss, Kiss Bang Bang, written and directed by Shane Black (“Lethal Weapon”).

Bernsen has also starred in an impressive string of films for television including the romance western Love Comes Softly for The Hallmark Channel with Katherine Heigl, Right To Die, a film in the Showtime series Masters Of Horror; Line of Fire: The Morris Dees Story, in which he portrayed the role of civil rights lawyer Morris Dees; and Love Can Be Murder, as a gumshoe ghost in the lighthearted NBC mystery romance with Jaclyn Smith. Other telefilm roles include Full Circle, Riddler’s Moon, The Dentist, The Dentist II, Two of Hearts and USA Network’s Call Me: The Rise and Fall of Heidi Fleiss. guest star roles on the primetime series Law And Order: Criminal Intent, NYPD Blue, West Wing, Boston Legal, The New Adventures Of Old Christine, Criminal Minds and Castle.

In addition to his acting, producing, writing and directing chores, Corbin has one of the largest snow globe collections in the world, in excess of over 8000, which he keeps displayed at his production company.

The eldest of three children, Bernsen was born in North Hollywood to a producer father and his mother, actress Jeanne Cooper who has starred as Katherine Chancellor on the CBS soap The Young And The Restless for over 38 years who he continues to draw inspiration from.

Bernsen makes his home in Los Angeles with his wife, actress Amanda Pays and their four sons.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Charles Sherman

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.