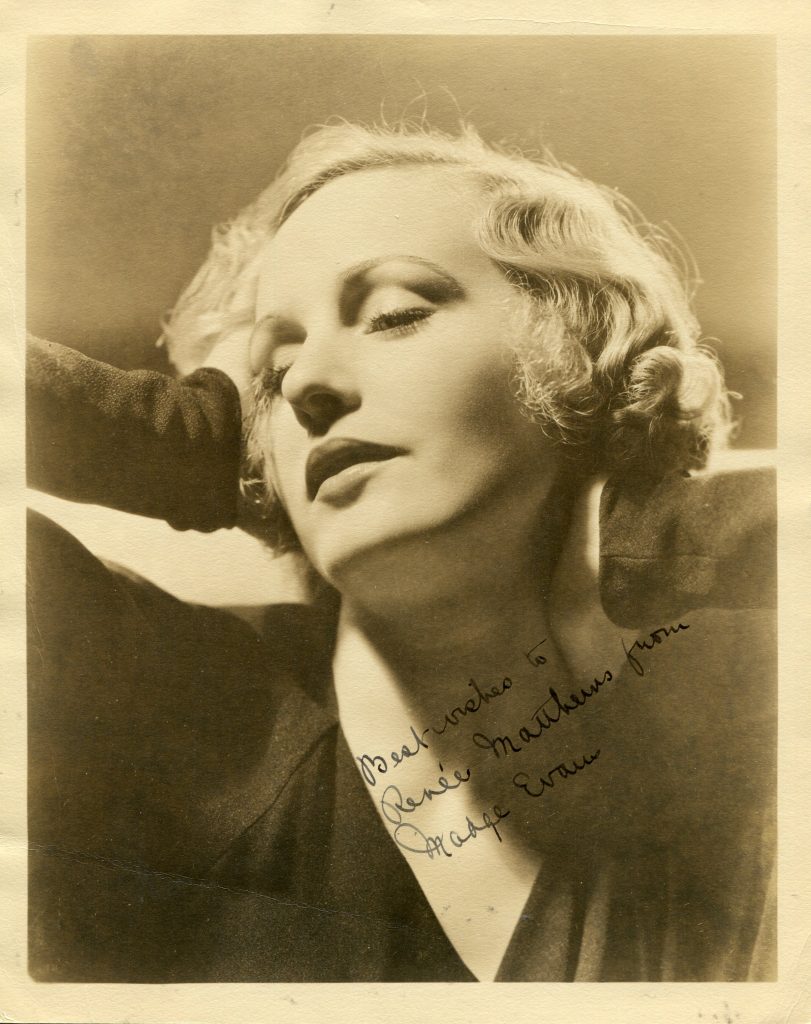

Tom Vallance’s obituary in “The Independent”:

Born in Hollywood, Los Angeles, in 1925, Guild was a student at the University of Arizona with no previous acting experience when Zanuck saw her photograph on the cover of Life magazine (part of a layout on campus fashions) and decided to sign her to a contract. After a considerable period of training and publicity, she was given a leading role in Somewhere in the Night (1946), an intriguing thriller directed and co-written by Joseph L. Mankiewicz.

It was his second film as a director, and Guild later recalled the close collaboration between the director and his editor James Clark. “Joe was smart enough to know that he didn’t know enough about editing. He had Clark on the set every day to pick his [Clark’s] brains, and he really listened.”

Somewhere in the Night was part of the film noir cycle popular at the time, its amnesiac hero journeying through the seedier parts of Los Angeles in his quest to discover his identity and his possible link with a murder. Guild played a night-club singer who aids the hero in his quest and falls in love with him. She said later that Mankiewicz had lunch with her every day throughout the shooting and drew from her every detail of her life story, which he would use when preparing her for difficult scenes. “I never would have stayed in the picture if it hadn’t been for Joe,” she said, “because he really fed me every line.”

Mankiewicz was a notorious ladies’ man who had already had affairs with the Fox girls Linda Darnell and Gene Tierney, but Guild said that although she had a “wild, mad crush on him” their relationship was platonic:

He kissed me once, but there was nothing sexual about our relationship. He treated me like an intelligent woman instead of someone who was predominantly attractive. I think maybe he required attention from a younger woman with whom he could be professorial and pedantic. He asked me out a number of times, but I said “What about your wife?”

Guild was less enthusiastic about her leading man, John Hodiak, whom she found “very cold”, and the lack of chemistry between the two leads worked to the film’s detriment.

Fox centred much of the film’s advertising around their new star: “Meet that Guild girl – she rhymes with wild!” was their slogan. Variety commented: “There’s no quarrel with her performance as a newcomer but it carbon-copies too many other film lookers to stand out individually.”

Guild was next cast in John Brahm’s The Brasher Doubloon (1947), an underrated adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s thriller The High Window. It had the misfortune to be released after two superb Chandler adaptations, Edward Dmytryk’s Farewell My Lovely (1944) with Dick Powell and Claire Trevor, and Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep (1946) with Bogart and Bacall, and the two leads, Guild and George Montgomery, were considered a bland couple in comparison. Though Montgomery was too boyish as the private detective Philip Marlowe, Guild was effective as the strangely neurotic secretary to a wealthy widow (Florence Bates) who hires Marlowe to find a missing gold coin.

The Brasher Doubloon was a taut, atmospheric thriller with typically low-key noir photography, some fine supporting performances, notably those of Bates and Fritz Kortner, and a gripping plot, but its modest reception tempered the studio’s enthusiasm for their new discovery. After casting her as the girlfriend of an ex-vaudevillian’s son (Dan Dailey) in the nostalgic Give My Regards to Broadway (1948), Fox terminated Guild’s contract.

At United Artists, she played Marie Antoinette in Gregory Ratoff’s Black Magic (1949), dominated by Orson Welles’s grandiloquent performance as the 18th-century villain Cagliostro, and, after three inconsequential roles at Universal, in Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951), Little Egypt (1951) and Francis Covers the Big Town (1953), she retired from the screen.

In the mid-Forties she had been briefly married to the actor Charles Russell, by whom she had a daughter, and in 1950 she married the Broadway producer Ernest Martin (who co-produced Guys and Dolls, Can Can and Cabaret), a union that lasted for 25 years. The couple had a luxurious apartment in New York and a house in the South of France, and, when not travelling or gardening, Guild served on the Board of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre and worked with patients there. She and Martin, who had two daughters, were divorced in 1975, and Guild married John Bryson, a photojournalist, in 1978. They divorced in 1995.

Guild made a brief Hollywood comeback in 1971 when Otto Preminger, whom she had known since her Fox days, asked her to do a cameo as a magazine editor in his witty black comedy Such Good Friends, and shortly afterwards when her marriage to Martin was breaking up she expressed the hope, sadly unrealised, to reactivate her career, telling an interviewer:

I want to go back to work, and it’s really quite remarkable because when I worked before, the only thing I liked about my work was lunch. Now I love the camaraderie of just working. If I could do something other than acting I would. But acting is the only thing I ever made any money at, so I’m trying that first. And you know something? Now that I’m older, I like acting.

Nancy Guild, actress: born Hollywood, California 11 October 1925; married Charles Russell (one daughter; marriage dissolved), 1950 Ernest Martin (two daughters; marriage dissolved 1975), 1978 John Bryson (marriage dissolved 1995); died East Hampton, New York 24 August 1999.