IMDB entry:

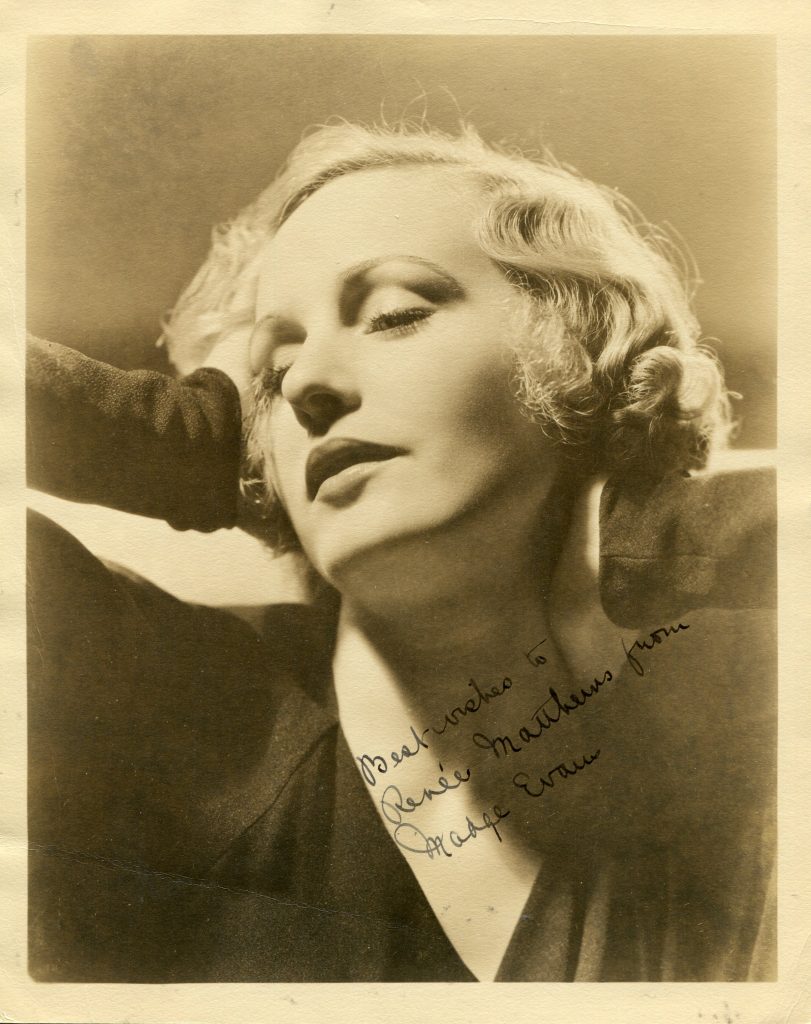

Lovely Madge Evans was the perennial nice girl in films of the 1930’s. By then, she had been in front of the camera for many years, starting with Fairy Soap commercials at the age of two (she sat on a bar of soap holding a bunch of violets with the tag line reading “have you a little fairy in your home?”). ‘Baby Madge’ also lent her name to a children’s hat company. In 1914, aged five, she was picked out by talent scouts to appear in theWilliam Farnum movie The Sign of the Cross (1914), followed by The Seven Sisters(1915) with Marguerite Clark.

By the end of the following year, she had amassed some twenty film credits, appearing with such noted contemporary stars as Pauline Frederick or Alice Brady. All of her early films were made on the East Coast, at studios in Ft.Lee, New Jersey. In 1917 (aged eight), Madge made her Broadway debut in ‘Peter Ibbetson’ with John Barrymore andLionel Barrymore. She resumed her stage career in 1926 as an ingenue with ‘Daisy Mayme’ and the following year appeared with Billie Burke in Noel Coward‘s costume drama ‘The Marquise’ (1927).

Her pleasing looks and personality soon attracted the attention of Hollywood and she was eventually signed by MGM in 1931. During the next decade, she appeared in several A-grade productions, notably as Lionel Barrymore’s daughter in MGM’s Dinner at Eight(1933) and as the dependable Agnes Wickfield in one of the best-ever filmed versions ofDavid Copperfield (1935). She co-starred opposite James Cagney in the gangster movieThe Mayor of Hell (1933), Spencer Tracy in The Show-Off (1934) and listened to Bing Crosby crooning the title song in Pennies from Heaven (1936). Madge received praise for her performance as the star of Beauty for Sale (1933) and The New York Times review of January 13 1934 described her acting in Fugitive Lovers (1934) (opposite Robert Montgomery ) as ‘spontaneous and captivating’. Many of her ‘typical American girl’ roles did not allow her to express aspects of the greater acting range she undoubtedly possessed. Too often she was cast as the ‘nice girl’ – and those rarely make much of a dramatic impact. On the few occasions she was assigned the role of ‘other woman’ , such as the Helen Hayes-starrer What Every Woman Knows (1934), audiences found her character difficult to believe and disassociate from her all-round wholesome image. When her contract with MGM expired in 1937, Madge wound down her film career and, following her 1939 marriage, concentrated on being the wife of celebrated playwright Sidney Kingsley. She last appeared on stage in one of his plays, “The Patriots”, in 1943.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: I.S.Mowis

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

“New York Times” obituary from 1982:

Madge Evans, a popular actress who frequently portrayed the cleancut, decent American woman in films and on stage during the 30’s, died of cancer Sunday night at her home in Oakland, N.J., where she had lived for many years with her husband, the playwright Sidney Kingsley. She was 71 years old.

Miss Evans appeared in such films as ”The Greeks Had a Word for Them” (1932), ”Dinner at Eight” (1933), ”Stand Up and Cheer” (1934), ”David Copperfield” (1935) and ”Pennies from Heaven” (1936).

On Broadway, she played in ”Daisy Mayme” (1926), ”Our Betters” (1928), ”Philip Goes Forth” (1931), ”Here Come the Clowns” (1938) and ”The Patriots” (1943), which was written by Mr. Kingsley.

The actress was born on the West Side of Manhattan on July 1, 1909, and first appeared professionally in an advertisement, as a child model perched on a huge bar of Fairy Soap.

While modeling, she was spotted as a potential child star. At the age of 5, she appeared in a silent-film version of ”The Sign of the Cross” with William Farnum. By 6, she had acted in 20 films made in studios in Fort Lee, N.J.

At 15, Miss Evans was seen in ”Classmates,” a film with Richard Barthelmess. In 1926, she made her first stage appearance in ”Daisy Mayme” and thereafter her career alternated between films and Broadway. The handsome young actress appeared in films with such stars as Spencer Tracy, Bing Crosby, Warner Baxter, John and Lionel Barrymore, James Cagney, Al Jolson, Robert Young, Lee Tracy, Richard Dix and Robert Montgomery.

While in ”Brief Moment” at the Ogunquit Playhouse in 1939, the 30-year-old actress was married to Mr. Kingsley. Thereafter, Mr. Kingsley said recently, she devoted much of her time to helping him with the research and writing of his plays. He described her as his collaborator in the theater in every sense.

The above “New York Times” obituary can also be accessed online here.