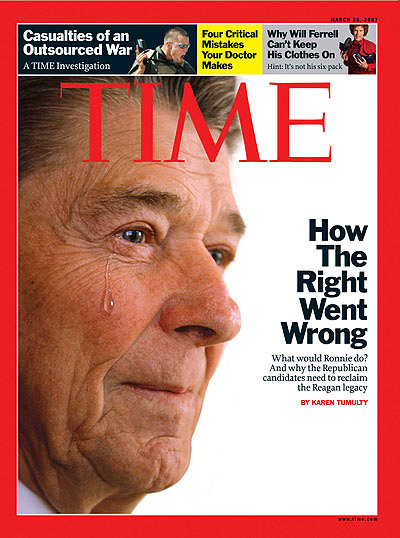

An affable Midwesterner, Ronald Reagan parlayed his athletic good looks and undeniable charisma into a middling career in the movies, but it was the smaller screen that he would eventually master on his way to two terms as governor of California and ultimately as the 40th President of the United States. In that role of a lifetime, the ‘Great Communicator’ displayed constant optimism and a jaunty self-confidence, both of which endeared him to millions, despite revelations of wrongdoing by aides or occasional failures in foreign policy. Reagan acquired almost mythic status leading the charge John Wayne-style to vanquish the Evil Empire, but detractors would say, “At what cost?” An opponent of Big Government on one hand, he reduced government expenditures through massive domestic budget cuts while feeling no compunction about the huge federal deficits that piled up due to unprecedented peacetime military spending. True, he brought the Soviet Union to its knees, but there is also a legacy of social Darwinism evident in the ever-widening gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots.”

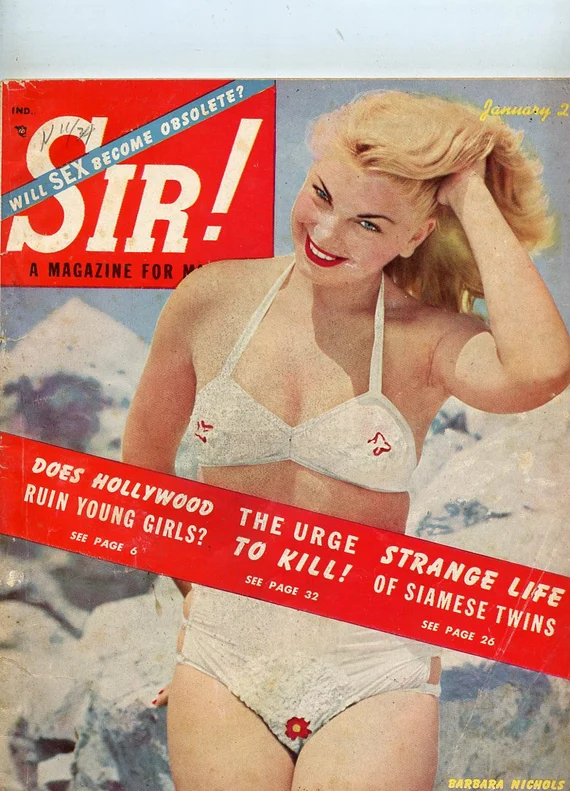

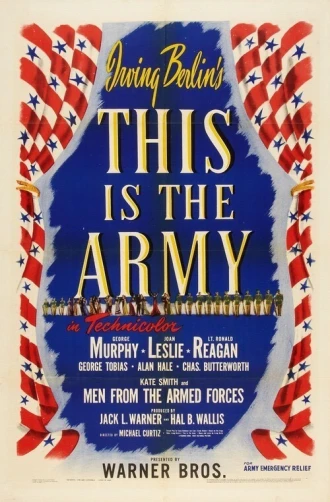

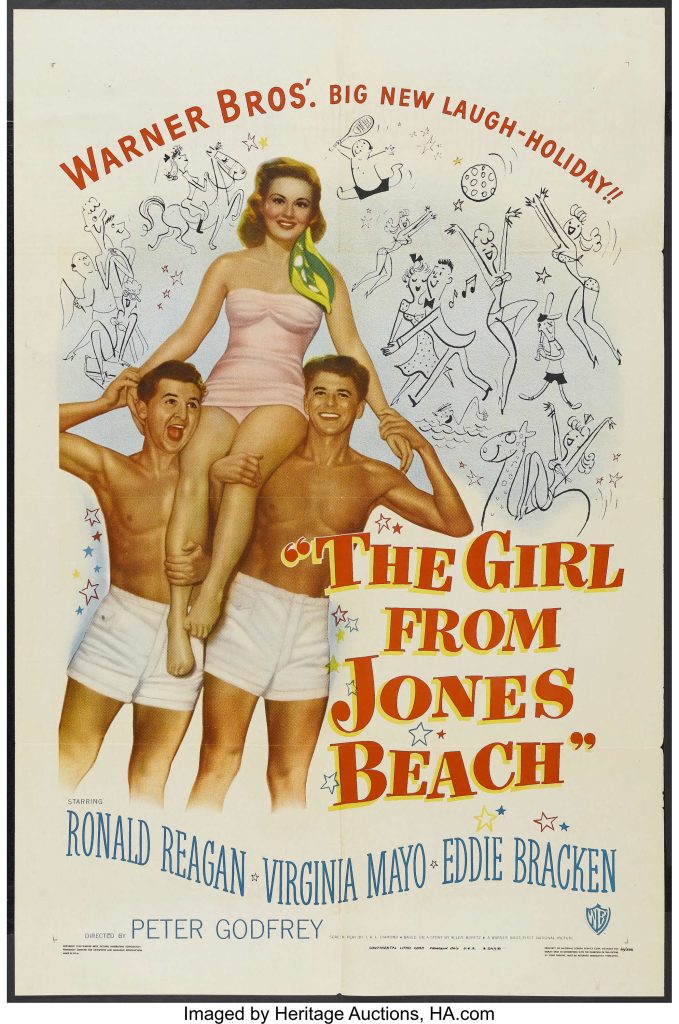

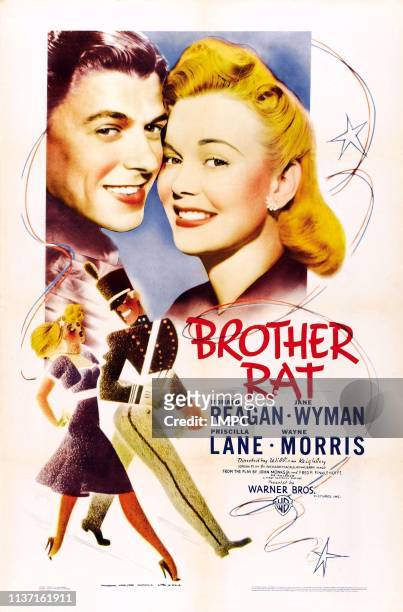

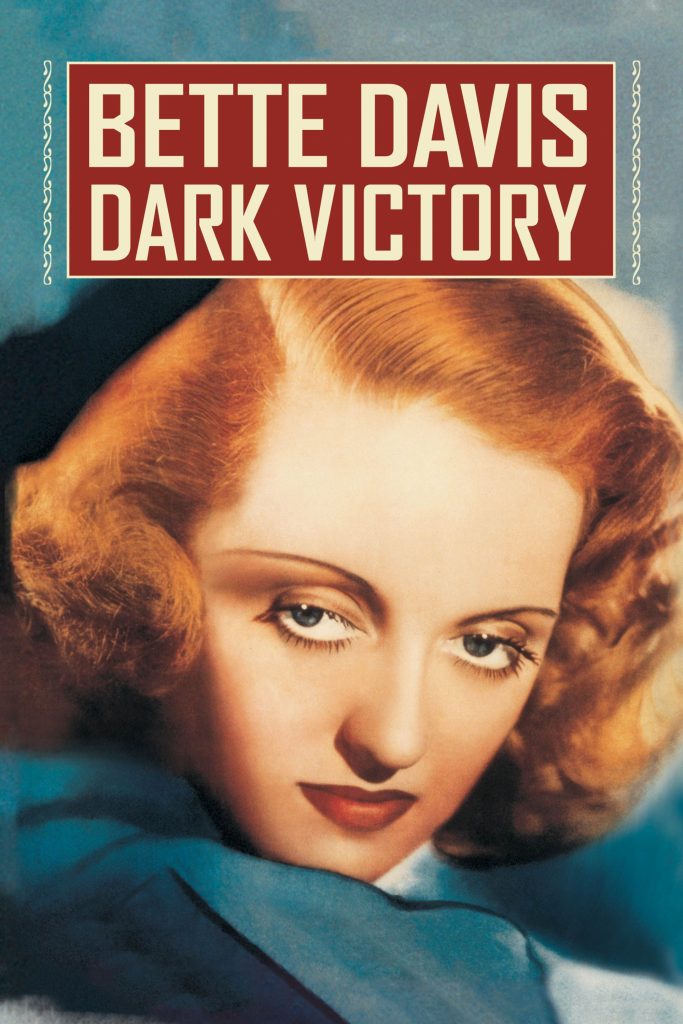

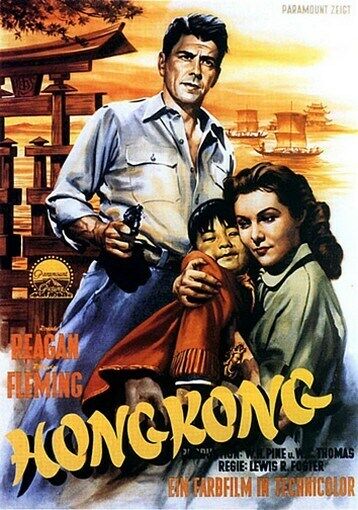

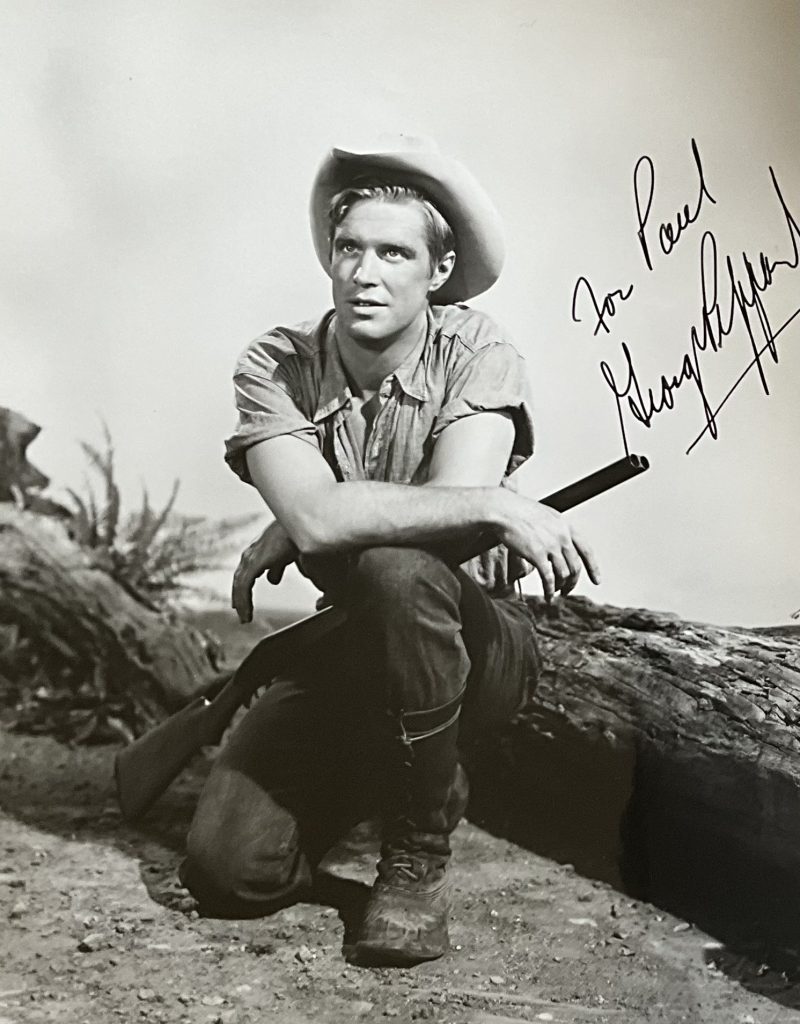

‘Dutch’ Reagan began his career as a sportscaster in Iowa, broadcasting the games of the Chicago Cubs, before a screen test earned him a contract at Warner Bros. (at whose insistence he dropped the nickname). Debuting as a radio announcer in “Love Is on the Air” (1937), he went on to appear in more than 50 films over the next two decades, proving a popular romantic lead in B pictures and a reliable support and/or a hero’s stolid pal in the studio’s A-list features. He was certainly memorable as George Gipp, Notre Dame’s dying football star, in “Knute Rockne–All American” (1940), and most TV prints have restored his “win just one for the Gipper” speech, cut because Pat O’Brien’s second-hand delivery of the line seemed enough exhortation to victory. He turned in what is almost universally considered his finest performance in “King’s Row” (1942), playing a character who has just had both legs amputated. Waking up from the anesthesia, he laments, “Where’s the rest of me?” (Reagan used the line as the title of his 1965 autobiography). He was also terrific as a compassionate but forceful American soldier in “The Hasty Heart” (1947), a stand-out in the midst of some box office bombs for him, but that film really belonged to Oscar nominee Richard Todd as the tragic Scotsman.

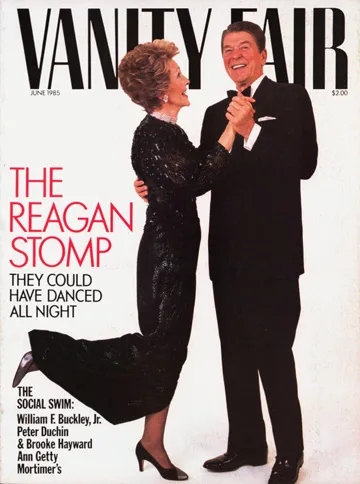

After serving as a captain in the US Air Force during WWII, Reagan became immersed in Hollywood politics and commenced his transformation from liberal New Deal Democrat to conservative Republican. As president of the Screen Actors Guild, he became embroiled in disputes about Communism in the film industry, and his conviction that Communist infiltration was undermining the nation’s institutions inspired the radical shift in his philosophy. Despite SAG’s affiliation with the American Federation of Labor, he negotiated contracts that greatly favored producers, but his flair for leadership helped him get elected to six one-year terms as the union’s president. His first marriage to Jane Wyman ended in part because of his increased political involvement (and what she perceived as his dullness), clearing the way for a later marriage to actress Nancy Davis, his biggest asset when he set his sights on higher office. Though his big-screen star had faded (his most notable film of the 50s, the schlocky “Bedtime for Bonzo” 1951, cast him opposite a chimp), he revived his popularity on TV as host of CBS’ “General Electric Theater” (1954-62) and traveled the nation as the company’s spokesman, preaching the fiery gospel of the Far Right.

Reagan recognized that TV was the perfect podium. During his eight-year run as goodwill ambassador for GE, the audience for any one episode rivaled the total number of people who had seen all of his movies. Having supported Richard M. Nixon in the 1960 race for President against John F. Kennedy, he then officially registered as a Republican in 1962, stumping for Nixon’s unsuccessful stab at the California governorship. His wife’s parents were intimates of Barry Goldwater, so it came as no surprise that he backed the Arizona senator’s bid for President in 1964. His conservative rhetoric honed to a razor’s edge, he went before the camera a week before the election and gave his stirring “A Time of Choosing” speech, a ringing defense of free enterprise and an attack on Communism cast in apocalyptic terms. Nearly $1 million flooded Republican coffers, and Reagan emerged as the GOP’s new star, despite Goldwater’s resounding defeat. Washington columnist David S. Broder declared it “the most successful national political debut since William Jennings Bryan electrified the 1896 Democratic convention with his ‘Cross of Gold’ speech.” Encouraged by friends to run for governor of California, the undeclared candidate and his wife took to the road and built grassroots support.

Reagan was twice the underdog in the 1966 election, first in the Republican primary, then against the Democratic incumbent Pat Brown (whose refusal to take his opponent seriously until it was too late doomed him to finish second by almost a million votes). Always quick with a quip, Reagan once remarked that a student demonstrator “had a haircut like Tarzan, walked like Jane, and smelled like Cheetah”, but his hard line approach to handling student unrest in the late 60s cost him votes, contributing to a much closer race in 1970. Many observers have noted that Reagan’s record as Governor was not as good as he claimed but not as bad as his critics maintained. In general, his eight-year record reflected a willingness to compromise in order to achieve his goals, such as his work with Democratic Speaker of the Assembly Bob Moretti to pass the nation’s first Welfare Reform Act in 1971. Though Reagan had initially reduced university funding, once the student protest movement had subsided, the higher education system began to receive large funding increases. He left office high in the popularity polls, no longer seen as an amateur politician from Hollywood, though few considered him a major statesman.

After his unsuccessful bid for the 1976 Republican presidential nomination, Reagan established a political action committee that raised and distributed money to Republican candidates at all levels during the 1978 mid-term election, creating a national network of loyal partisans for his 1980 campaign. He easily defeated his only competition in the primary, George Bush, then attacked incumbent President Jimmy Carter’s “failed” economic policies that had resulted in 12 percent inflation and eight million people unemployed, winning the November election overwhelmingly. (The fiasco of the hostages in Iran provided the final nail in the Carter coffin.) Early in his first year in office, he survived an assassin’s bullet and achieved a certain inviolability for the rest of his Presidency. Though it seemed that Reagan brought unemployment and inflation under control, he may have just been in the right place at the right time, his economic program benefiting more from a change in Federal Reserve Board policy than from the vaunted supply-side (“voodoo”) economics at its center.

His mastery of the TV medium made Reagan one of our most beloved Presidents. When those little red lights on the cameras lit up, he glowed like a man welcoming his best friend, and somehow he made you feel like you were his best friend, elevating the Mr. Nice Guy role learned at his mother’s knee and refined in the Hollywood crucible into high art. Reagan never shied away from his Hollywood history and often made it work to his advantage: his friendships with celebrated liberals-turned-conservative stars such as Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, and James Stewart bolstered his populist appeal; his speeches frequently cribbed lines from popular movies, such as Clint Eastwood’s famous “Go ahead, make my day” dialogue; and he often invoked his own sometimes-less-than-stellar film career with an appealing and self-depricating air. His example would continue to influence after his presidency: presidential successor Bill Clinton most cannily used his celebrity connections to define his political image, while another generation of movie-star-turned-Republican-politician, Arnold Schwarzenegger, drew inspiration from Reagan’s example and managed to follow in his footsteps as Governor of California.

In Showtime’s controversial cable film, “The Reagans” (2003), a nice guy did finish first and got the girl too, for no examination of the man can ignore his leading lady. Without Nancy, it is safe to say he would have never been President. Together they stepped from the cinema screen, her social contacts helping to start and keep him on the road to the White House. Once there, she wielded tremendous power as the self-effacing half of a very successful team. It was a perfectly scripted celluloid love story, except for the sad twist that had her standing by him at the end as he succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease, a condition which plagued the former president in the final decade of his life before his death at age 93 in 2004. Their romance remains the best part of the Reagan legacy because, unlike in the movies, their actions effected the entire world. It will be up to history to record just how positive an effect they had.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online

here.