Nanette Fabray starred in one of the major MGM musicals, “The Band Wagon” in 1953 with Fred Astaire, Jack Buchanan and Cyd Charisse. She made her film debut in 1939 in “The Private Lives of Elizabeth & Essex” with Bette Davis and Errol Flynn. Her other movies include “The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima” in 1952 and “The Happy Ending” with Jean Simmons and Teresa Wright in 1969. She is the aunt of Shelley Faberes.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

A sparkling, entertaining, highly energetic presence ever since her early days (from age 4) as a singing and tap dancing child vaudevillian, Nanette Fabray (born Ruby Fabares in San Diego) was once billed as “Baby Nanette” and working with the top headliners of the era, notably Ben Turpin, in the Los Angeles area. She also sang on radio. It was widely rumored that she appeared in the “Our Gang” (“Little Rascal”) film shorts of the late 1920s; however, this was not true. Later the young hopeful received a scholarship to theMax Reinhardt School of the Theatre and appeared in the school’s productions of “The Miracle”, “Six Characters in Search of an Author” and “A Servant with Two Masters”, all in 1939.

The musical comedy stage, however, would be Nanette’s forte. Appearing in such hit New York productions as “Meet the People” (1940), “Let’s Face It” (1941), “By Jupiter” (1943) and “Bloomer Girl” (1945), she capped this period of great productivity earning awards for her Broadway work in “High Button Shoes” (1947 – Donaldson Award), and “Love Life” (1948 – Tony and Donaldson Awards).

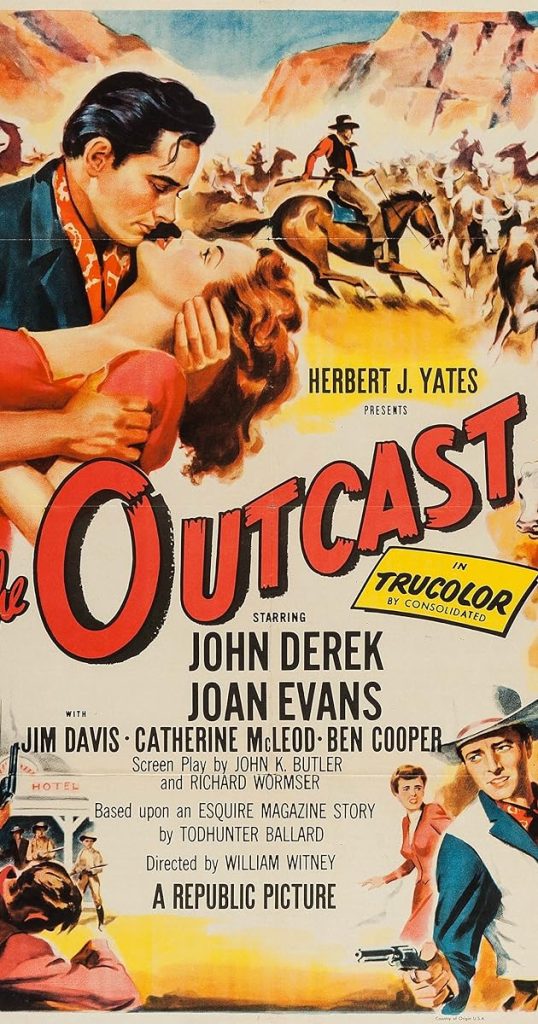

Strangely, Nanette never obtained a strong foothold when it came to film. Aside from secondary roles in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) starring Bette Davisand Errol Flynn, and the melodrama A Child Is Born (1939), her one claim to movie fame would be her vital participation in the blockbuster MGM musical The Band Wagon (1953) in which she memorably performed the songs “That’s Entertainment” and “Louisiana Hayride,” and joined Fred Astaire and Jack Buchanan in the standout “Triplets” number.

Into the 1950s, Nanette started checking out what TV could do as a possible medium for her. It did a lot. She managed a fine feat by winning two consecutive Emmy awards asSid Caesar‘s partner on the now-called Caesar’s Hour (1954) following the departure of the seemingly irreplaceable Imogene Coca earlier. This led to Nanette eventually starring in her own sitcom, the short-lived Westinghouse Playhouse (1961) (aka “Yes, Yes, Nanette”), in the role of a Broadway star who becomes a makeshift mom after marrying a widower (Wendell Corey) with two children.

Broadway musicals continued to flourish with perfs in “Arms and the Girl” (1950) and “Make a Wish” (1951). Nanette later copped another Tony nomination starring as a fictional “First Lady” opposition “President” Robert Ryan in the musical “Mr. President” (1962). Other tailor-made stage vehicles for her came in the form of “Plaza Suite”, “Wonderful Town”, “Never Too Late”, “Last of the Red Hot Lovers” and “Cactus Flower”, among others.

On the TV front, Nanette adjusted well into a lively and graceful support player. She served up a number of delightfully daffy moms, wisecracking friends and intrusive relatives in guest appearances — sometimes alongside her own niece, actress Shelley Fabares, as was in the case of their regular roles on One Day at a Time (1975). Nanette was also a popular game show personality during the 60s and 70s, appearing on The Hollywood Squares (1965), The New High Rollers (1974), Password All-Stars (1961) andThe Match Game (1962), among others. The singer-comedienne also could be counted on for TV musical variety appearances courtesy of headliners Dinah Shore, Andy Williams,Dean Martin and Carol Burnett.

Most importantly, Nanette’s humanitarian efforts over the years have been long recognized. A positive force as a hearing-impaired performer, she has given much time and effort in achieving equality for all types of handicapped and disabled people, including actors. Nanette is the widow (since 1973) of writer and sometime director/producer Ranald MacDougall, appearing in a few of his credited works, including the film Cockeyed Cowboys of Calico County (1970), the TV pilot Fame Is the Name of the Game (1966) and the TV-movie Magic Carpet (1972). She and MacDougall have one child. Still as lively as ever, Nanette appeared most recently in an L.A. musical revue entitled “The Damsel Dialogues” (2007).

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net