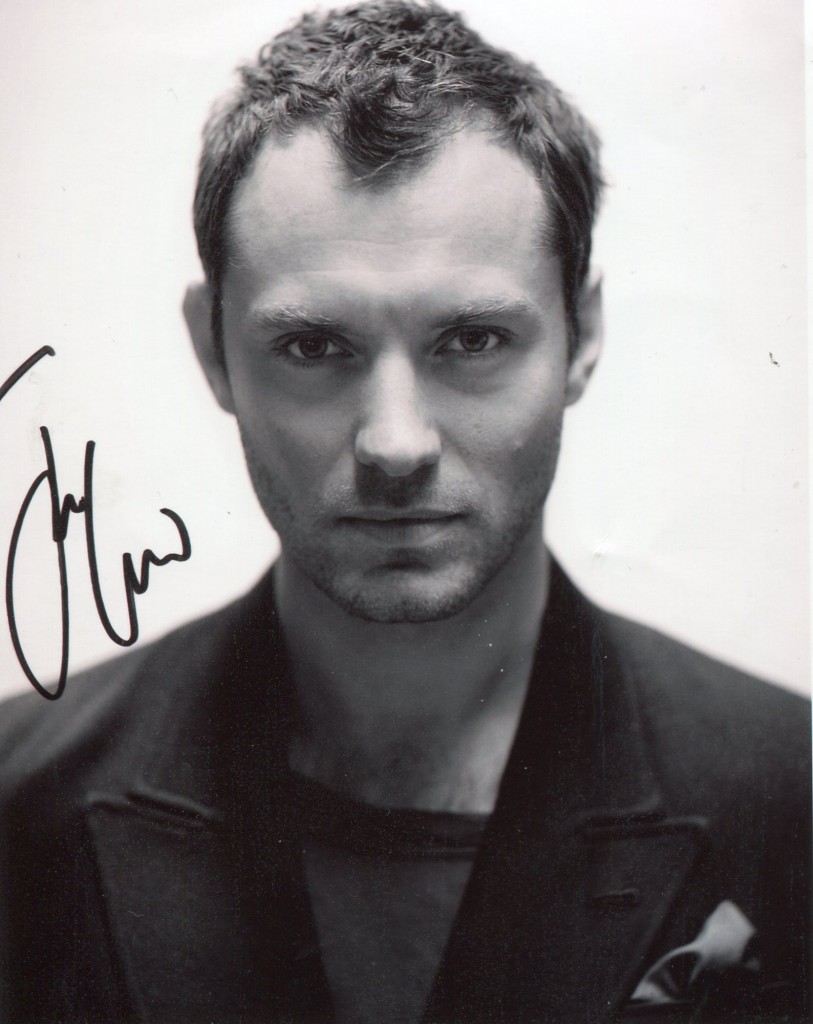

Jude Law was born in 1972 in London. His first major break in film was in “The Talented Mr Ripley” in 1999. Other movies since include “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil”, “Cold Mountain” and “Sherlock Holmes”.

TCM overview:

Plagued with being called a heartthrob and a Golden Boy, British actor Jude Law managed to develop into a respected actor known for tackling challenging and often flawed characters. Though he struggled a bit early in his career to make a name for himself, Law finally burst onto the scene full force with his Oscar-nominated performance in “The Talented Mr. Ripley” (1999). From there, he was suddenly everywhere onscreen, playing a Russian sniper battling a Nazi sharpshooter during the Battle of Stalingrad in “Enemy at the Gates” (2001), a scarred assassin fond of photography in “Road to Perdition” (2002), and a Confederate soldier presumed dead and struggling to make in home in “Cold Mountain” (2003). Though he was often the subject of tabloid fodder due his trouble-plagued relationship with starlet Sienna Miller, Law oscillated between small indies like “I [Heart] Huckabees” (2004) and “Breaking & Entering” (2006) and large-scale studio movies like “The Aviator” (2004) and “Sherlock Holmes” (2009). .

Born on Dec. 29, 1972 in Lewisham, England, a borough in southwestern London, Law was the son of schoolteachers who encouraged their son to act at an early age. When he was 12 years old, Law began performing with the National Youth Music Theatre. A leading role in “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat” led to his TV debut in a musical based on Beatrix Potter’s “The Tailor of Gloucester” (1990). That same year, Law dropped out of school for the British soap, “Families.” Fourteen months after his debut, Law left the series and returned to the stage, touring Italy as Freddie in “Pygmalion” and making a splash in London in “The Fastest Clock in the Universe.” In 1994, Law made an impression on theatergoers in both London and New York as a young man coping with his suffocating parents in “Les Parents Terrible,” particularly for an extended bathing scene in the second act which required complete nudity. Making enough of an impression, he was the only member of the English production invited to reprise his role on Broadway and was honored with a Tony Award nomination for his effort.

Law’s first film role – he played a passive car stealing street kid in “Shopping” (1994) – did little to propel him into the consciousness of American audiences. This set an unfortunate pattern for his early film career throughout much of the 1990s, during which he delivered strong turns in under-performing features. Often touted as the “next big thing,” Law would find himself quickly relegated to the “Who’s he?” list after a string of disappointing films. In 1997 alone, he offered three diverse portraits: the spoiled Lord Alfred Douglas in the well-intentioned biopic “Wilde,” an alcoholic paraplegic in “Gattaca,” and a bisexual hustler who ends up a murder victim in the based-on-fact “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.” In each case, the actor brought energy and charisma to the screen, yet each film failed to find much audience support. His losing streak continued with the barely released “Music From Another Room” (1998) with Jude starring as an artist who reconnects with a girl at whose he birth he assisted, and “The Wisdom of Crocodiles” (1998) as a vampire-like predator. While many believed that David Cronenberg’s sci-fi thriller “eXistenZ” (1999) might finally catapult Law onto the A-list, it proved too esoteric for mainstream audiences.

Law finally caught a break when Anthony Minghella tapped him to play the decadent playboy Dickie Greenleaf who becomes an object of envy to Matt Damon’s “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” Law was perfectly cast, shading the character with – as Janet Maslin wrote in her New York Times review – “the manic, teasing powers of manipulation that make him ardently courted by every man or woman he knows. During the first half of the film, Dickie is pure eros and adrenaline, a combination not many actors could handle with this much aplomb.” With talk of an Oscar nomination – which he later received – Law finally seemed truly on the verge of fulfilling the predictions of his becoming a movie star, though he would take his time getting there, cultivating pet projects before stepping up the pace of his soon-to- skyrocket film career. Prior to the release of “Ripley,” he returned to the London stage and earned strong notices in “‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore,” as well as making his directorial debut with a segment of the omnibus TV-movie “Tube Tales” (1999). Along with his wife Sadie Frost, whom he had met on the set of “Shopping,” and best mates Johnny Lee Miller, Ewan McGregor and Sean Pertwee, Law formed the production company Natural Nylon, with a slate of films in various stages of development.

As predicted, Hollywood came looking for him again in 2001 to take on the leading role in “Enemy at the Gates.” His enigmatic performance soon led to an inspired turn as a gigolo robot in Spielberg’s highly anticipated “A.I.” From there, Law would soon become a highly-coveted talent among Hollywood royalty. In 2002, he had a supporting role as a murderous photographer opposite Tom Hanks in “Road to Perdition,” before coming into his own as a leading man in 2003 when he took over a role initially for Tom Cruise opposite Nicole Kidman and Renee Zellweger in director Anthony Minghella’s “Cold Mountain” an adaptation of Charles Frazer’s best-selling Civil War melodrama. Playing Confederate Army deserter Inman, who flees his unit to return to his beloved Ada (Kidman) at Cold Mountain and faces incredible hardship on his long, harrowing journey back, Law was an utterly believable and compelling screen presence. The actor’s work was rewarded with a spate of critical recognition, including an Academy Award nomination as Best Actor. Of course, his was also subject to some of the prices of fame, which included intense media scrutiny of the gradual, messy breakup of his marriage to Frost.

Law’s next big-screen entry was the retro-yet-original action-adventure “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow” (2004) opposite Gwyneth Paltrow and Angelina Jolie, in which he played the titular character, a daring aviator in an Art Deco New York, battling giant robots and searching for missing scientists. “Sky Captain” was the first in a succession of Law-headlined films that were released in late 2004: He next appeared in the ensemble of writer-director David O. Russell’s “existential comedy” “I [Heart] Huckabees” as Jason Schwartzman’s rival, an executive climbing the corporate ladder at retail superstore Huckabees, whose seemingly perfect life is explored by a pair of existential detectives. Law had nearly dropped out of the film in favor of a Christopher Nolan project until Russell reportedly ran into Nolan at a Hollywood party, yanked him into a headlock and demanded he release Law. To the surprise of none, the following day the actor called to discuss his “Huckabees” role with no mention of the incident. Law then took on the titular caddish rogue with a comeuppance coming (originally played by Michael Caine) in a remake of the 1960s British comedy, “Alfie.”

He next appeared in the Mike Nichols-directed drama “Closer” opposite Julia Roberts, Natalie Portman and Clive Owen as a pair of couples whose relationships become messily intertwined; the performance was Law’s best of the busy year. The actor also gave his all when he had a cameo as the suave but debauched Hollywood superstar Errol Flynn in Martin Scorsese’s Howard Hughes biopic “The Aviator.” He closed the year as the voice of the title role in the children’s fantasy “Lemony Snicket’s Unfortunate Series of Events.” At the 2005 Oscar ceremony, Law’s now notable ubiquitous visage was notoriously skewered by host Chris Rock, who wondered who Law was to get so many roles, prompting über-serious Sean Penn, who was filming “All the King’s Men” with the actor, to defend Law’s talent from the stage. Later that year more unwanted publicity ensued when Law released a statement apologizing to his then-fiancée Miller for having an affair with his children’s nanny three months into their seven-month engagement. Not surprisingly, the British and American tabloids had a field day. The couple attempted to reconcile, but ultimately called it quits.

In “All the King’s Men” (2006), Steven Zaillian’s botched rehash of Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Law joined a promising cast that included Penn, Kate Winslet, Anthony Hopkins, Patricia Clarkson and James Gandolfini. Unfortunately, talent could not make up for bad production all around, as the respected original film turned out to be a laughing stock of a remake that was plagued by bad Southern accents, weak acting and a poorly-conceived script. Law next starred in a more palpable film, “The Holiday” (2006), a romantic comedy centered on two women – one British (Kate Winslet) and the other American (Cameron Diaz) – whose torn love lives prompt them to cross the ocean and switches houses for the Christmas holiday. Meanwhile, Law collaborated again with director Anthony Minghella for “Breaking and Entering” (2006), playing a partner at a thriving architecture firm who embarks on a quest of self-discovery and ultimately redemption when he hunts for the burglar who twice broke into his office and stole all his company’s high-tech equipment.

In another remake, “Sleuth” (2007), a play by Anthony Shaffer turned into a 1972 film starring Michael Caine and Laurence Olivier, Law played Milo Tindle (Caine’s character in the original film version), a hairdresser being set up by Andrew Wyke, an older, but wealthy society man (Caine assuming the Olivier role) determined to exact revenge on Tindle for stealing his wife. Following a turn as a celebrity supermodel in Sally Potter’s ensemble media satire “Rage” (2009), Law joined Johnny Depp and Colin Farrell in portraying a transformed version of Heath Ledger’s character in “The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus” (2009), following the overdose death of the actor in 2008. Returning to blockbuster filmmaking, he portrayed Dr. Watson to Robert Downey, Jr.’s titular “Sherlock Holmes” (2009), a rousing action movie that was a global hit at the box office. Meanwhile, Law rekindled his relationship with Miller despite fathering a child after his brief dalliance with model Samantha Burke in 2009, though the couple again split two years later. After starring with Forest Whitaker in the sci-fi thriller “Repo Men” (2010), Law was a messianic conspiracy theorist in Steven Soderbergh’s thriller “Contagion” (2011), which focused on the death and destruction caused by a rapidly spreading virus.

Reprising his role as Dr. Watson, Law starred with Downey, Jr., in the commercially successfully, but critically derided sequel “Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows” (2011). Working with Martin Scorsese in the Oscar-nominated “Hugo” (2011), he was the deceased father of the titular Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), a young boy living in the walls of Paris’ famed Gare Montparnasse railway station. After co-starring with Ben Foster, Rachel Weisz and Anthony Hopkins in the foreign-made drama “360” (2012), Law had a leading role as Alexei Karenina to Keira Knightley’s titular “Anna Karenina” (2012), Joe Wright’s Academy Award-nominated adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s literary masterpiece. From there, he voiced Pitch Black the Boogeyman in the animated “Rise of the Guardians” (2012), and made some news for dropping out of filming the indie film “Jane Got a Gun” in 2013, the day after director Lynne Ramsay exited the film. Law had signed on to the project exclusively to work with Ramsay.