Muriel Angelus was born in 1909 in London of Scottish parents. Her first movie was the silent “The Ringer” in 1928. Up until 1935 she alternated between making films and appearing on the London stage. She then went to Broadway to appear in the hit show “The Boys from Syracuse” with Eddie Albert. She then went to Hollywood where she made such films as “The Light that Failed” with Ronald Colman and Ida Lupino “The Great McGinty” directed by the great Preston Sturges with Brian Donlevy. On her marriage in 1943 she retired from acting. Muriel Angelus died at the age of 95 in 2004.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

The memories are vague when it comes to recalling this London-born leading lady, but Muriel Angelus did have her moments. She managed to appear in a few classic Broadway musical shows and Hollywood films before her early retirement in the mid-1940s. Of Scottish parentage, the former Muriel Findlay developed a sweet-voiced soprano at an early age. She made her singing debut at 12, eventually changing her name and becoming a popular music hall performer. She entered films toward the end of the silent era with The Ringer (1928), the first of three movie versions of the Edgar Wallace play. Her second film Sailor Don’t Care (1928) was important only in that she met her first husband, Scots-born actor John Stuart. Her part was excised from the film. Though in her first sound picture Night Birds (1930), she got to sing a number, most of her films did not usurp her musical talents. The sweet-natured actress who played both ingenues and ‘other woman’ roles co-starred with husband Stuart in No Exit (1930), Eve’s Fall (1930) and Hindle Wakes (1931), and appeared with British star Monty Banks in some of his farcical comedies, including My Wife’s Family (1932) and So You Won’t Talk (1935). Muriel received a career lift with the glossy musical London hit “Balalaika” and a chain of events happened with its success. It led to her securing the pivotal role of Adriana in “The Boys From Syracuse” and, in turn, a contract with Paramount Pictures. Divorced from Stuart by this time, Muriel settled in Hollywood and made her best films while there. She was touching as girlfriend to blind painter Ronald Colman in The Light That Failed (1939), a second remake of the Rudyard Kipling novel, and appeared to great advantage in Preston Sturges’ classic satire The Great McGinty (1940) as _Brian Donlevy_’s secretary. After scoring another long-running Broadway hit with “Early To Bed” in 1943, Muriel met Radio City Music Hall orchestra conductor Paul Lavalle while appearing on radio in New York and married him in 1946. She retired to raise a family in New England. They had a daughter, Suzanne, who later worked for NBC. Muriel pretty much stayed out of the limelight for the remainder of her life. She died at 95 in a Virginia nursing home in 2004, some seven years after her husband’s death.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

Guardian obituary 2004

Muriel Angelus

British actor who starred in films and stage musicals, memorably singing Falling In Love With LoveRonald BerganThu 2 Sep 2004 01.36 BST

One of Rodgers and Hart’s greatest hits, Falling In Love With Love, was first sung in the 1938 Broadway production of The Boys From Syracuse by Muriel Angelus, who has died aged 95. The New York Times critic thought her portrayal of Adriana in this musical adaptation of The Comedy Of Errors “a monument to precariously controlled wifely patience”, and that she sang “with exquisite sweetness”. Unfortunately, her sweetly exquisite soprano voice was heard too seldom in a career that began at the age of 12 and ended at 33.

Born in London of Scottish parents, the blonde Muriel Angelus Findlay began singing in music halls before entering films in 1928 in the silent The Ringer, the first of three versions of the Edgar Wallace play. A year later, she was in Germany for Maskottchen, based on an operetta by Walter Bromme, in which she played “the other woman”. If the producers had waited a few months for sound, they could have included the songs.Advertisementhttps://38e84c381af680794f0905d392a93a04.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

In her first talkie, Night Birds (1930), she got to sing a number in a West End revue, in which a detective, on the trail of her fugitive boyfriend, disguises himself as a chorus boy. More serious was Hindle Wakes (1931), the first sound version of Stanley Houghton’s 1912 play, where Angelus portrayed Beatrice Farrar, the respectable fiancee of Alan Jeffcote, a Lancashire mill-owner’s son, who refuses to go away with him for a naughty weekend. Instead, he takes a mill girl, only to return to Beatrice after the girl remembers her “place”. Jeffcote was played by the Scottish-born actor John Stuart, whom Angelus married during the shooting of the film.

They then appeared together in Let’s Love And Laugh (1931), an inconsequential comedy-drama in which she was the daughter of a publisher, and he an aspiring writer. She then embarked on several farcical comedies, some directed and starring Monty Banks (Mario Bianchi), the husband of Gracie Fields, with titles such as My Wife’s Family (1932), So You Won’t Talk (1935), and Blind Spot (1932), in which she played an amnesiac, a melodrama Angelus would have wanted to forget.

· Muriel Angelus, actor, born March 10 1909; died August 22 2004

In 1936, she starred in the Eric Maschwitz stage musical Balalaika at the Adelphi Theatre in London. Angelus was ravishing as Lydia, a ballet dancer and singer, who falls in love in Paris with an exiled Russian prince after the Bolshevik Revolution. It was the sort of thing that went down very well in the West End in the 1930s, and it ran for over a year. It led to Angelus being offered the role of Adriana in The Boys From Syracuse, and a contract with Paramount, for whom she made four prestigious films.

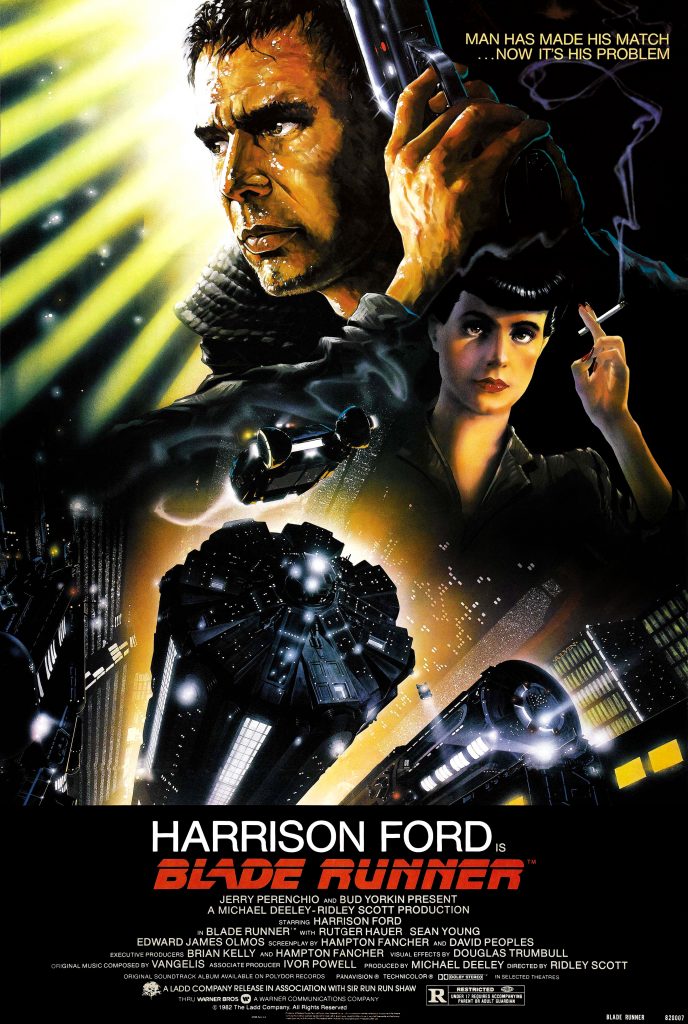

The first was William Wellman’s The Light That Failed (1939), the second remake of the Rudyard Kipling novel, which tells of the desperate attempt of a painter (Ronald Colman) to finish his greatest painting – of a prostitute (Ida Lupino) – before he goes blind. In a moving scene, Angelus, as the now blind artist’s girlfriend, has to hide the fact from him that the painting has been slashed by the prostitute in a jealous rage.

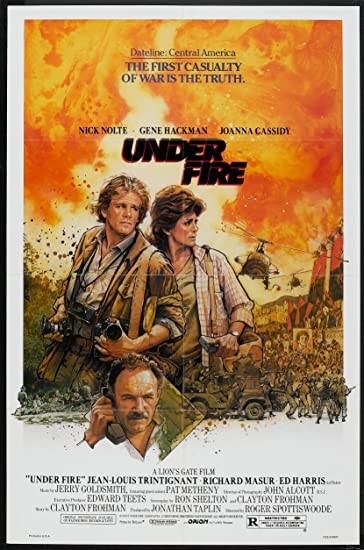

Of the three last films she made, all in 1940 – Safari, a studio-bound jungle melodrama with Douglas Fairbanks Jr as “the best hunter in West Africa”; The Way Of All Flesh, in which Angelus was a thieving adventuress; and The Great McGinty – the last is by far the most memorable. In this, Preston Sturges’ first feature, about a tramp (Brian Donlevy) who becomes state governor by craft and graft, Angelus played his secretary, offering to become his public wife for the sake of the “women’s vote”. Angelus triumphs as the sole character with half a conscience in one of Hollywood’s best satires.

After another success in a Broadway musical, Early To Bed (1943-44), as the madame of a bordello in pre-war Martinique, which people, for reasons known only to the librettist, keep mistaking for a girls’ school, Angelus left show business. In 1946, long divorced from Stuart, she married Paul Lavelle, the conductor of the Radio City Music Hall orchestra.

Fifteen years later, Lavelle and Angelus recorded Tribute To Rodgers And Hammerstein, in which, naturally, she sung Falling In Love With Love. She is survived by her daughter from her second marriage.