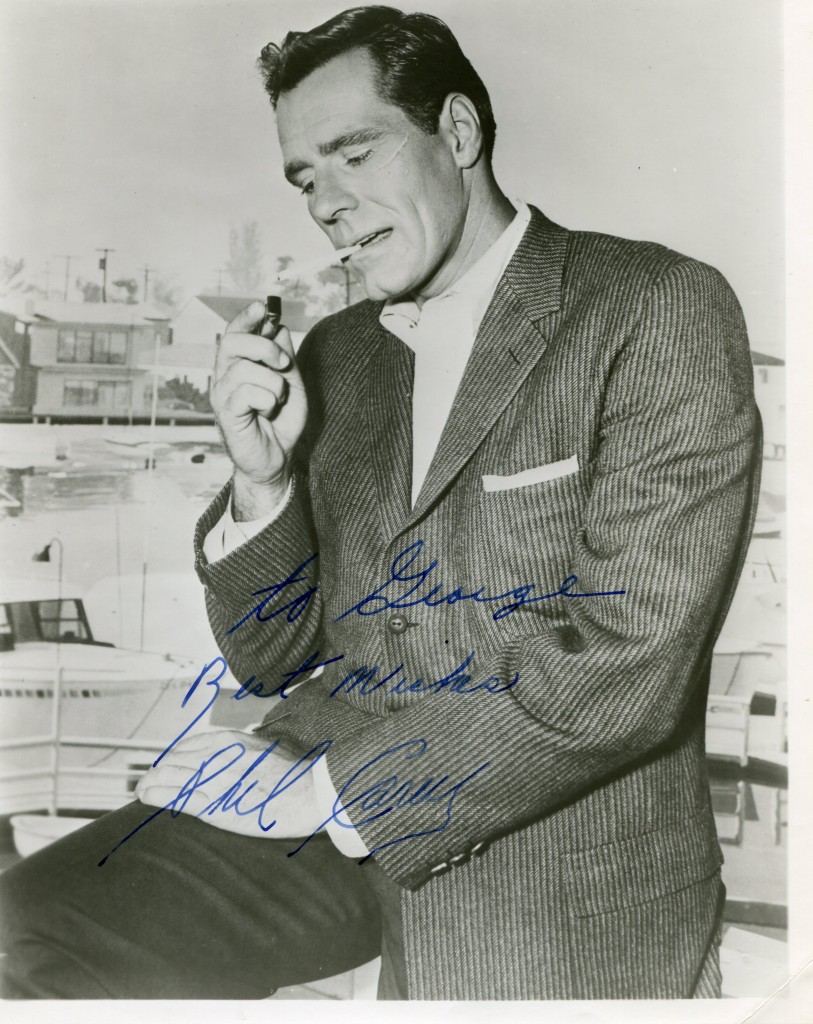

John Cassavettes was born in New York City in 1929. He is well regarded as an independent pioneer of American film. His first starring role on film was “Edge of the City” in 1957 with Sidney Poitier. He went on to make “Virgin Island” with Poitier again and Virginia Maskell, “Saddle the Wind” with Robert Taylor and “The Dirty Dozen”. He directed many movies starring his wife Gena Rowlands including “Faces”, “Minnie and Moskowitz”, “A Woman Under the Influence”, “Gloria” and “Love Streams”. Johhn Cassavettes died in 1989 at the age of 59.

TCM Overview:

Primarily known as an actor early in his career, John Cassavetes would later be regarded as one of the most daring and influential filmmakers of the 20th Century, attributed by many as the artist who shaped the current definition of independent film. As a young performer, Cassavetes found his early roles in mainstream productions like “Edge of the City” (1957) creatively unsatisfying. Determined to prove he could do better, he embarked on a three-year odyssey that yielded his debut as a writer-director – the racial identity drama “Shadows” (1959). Though not a commercial hit, “Shadows” earned Cassavetes enough critical acclaim to attract Hollywood, although the resulting films left him chaffing under the control of the studio system. In response, Cassavetes created a system of his own – one in which he would act in major productions like “The Dirty Dozen” (1967) and “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968) in order to fund independent endeavors of his own. Over the course of the next 15 years Cassavetes wrote, directed and occasionally performed in such thought-provoking works as “Faces” (1968), “Husbands” (1970), “Minnie and Moskowitz” (1971), “A Woman Under the Influence” (1974), “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie” (1976), “Gloria” (1980) and “Love Streams” (1984). Each film featured some combination of his frequent acting collaborators, including wife Gena Rowlands, Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara and Seymour Cassel. While professional acting was a mere means to an end, Cassavetes pursued his own artistic truth and provided audiences with new experiences through his deeply personal films.

Born John Nicholas Cassavetes on Dec. 9, 1929, in New York City, he was the son of Greek immigrants Nicholas John and Katherine Cassavetes. As a young boy, John spent most of the first seven years of his childhood in his parents’ homeland after they returned to Greece for an extended period. Although he barely spoke a word of English upon his family’s return, the outgoing boy eventually excelled in both academic and extra-curricular activities while attending schools in Long Island and New Jersey. Following high school graduation, he dabbled with the idea of studying literature at Colgate College; however, Cassavetes – a devoted film enthusiast – eventually enrolled at New York’s American Academy of Dramatic Arts, from which he graduated in 1950. Although his parents initially blanched at his decision to pursue acting, Cassavetes’ talent and determination soon earned their support. In addition to work with various theater companies, he picked up his first film credits with minor parts in productions like the noir “Fourteen Hours” (1951) and the romantic drama “Taxi” (1953). That same year, Cassavetes gained valuable experience as a stage manager and standby performer in the Broadway production of the farce “The Fifth Season.” Television soon provided the motivated young actor with an exceptional opportunity to hone his screen craft through dozens of appearances in such anthology series as “Kraft Theatre” (NBC, 1947-1958) and “Armstrong Circle Theatre” (NBC, 1950-57; CBS, 1957-1963).

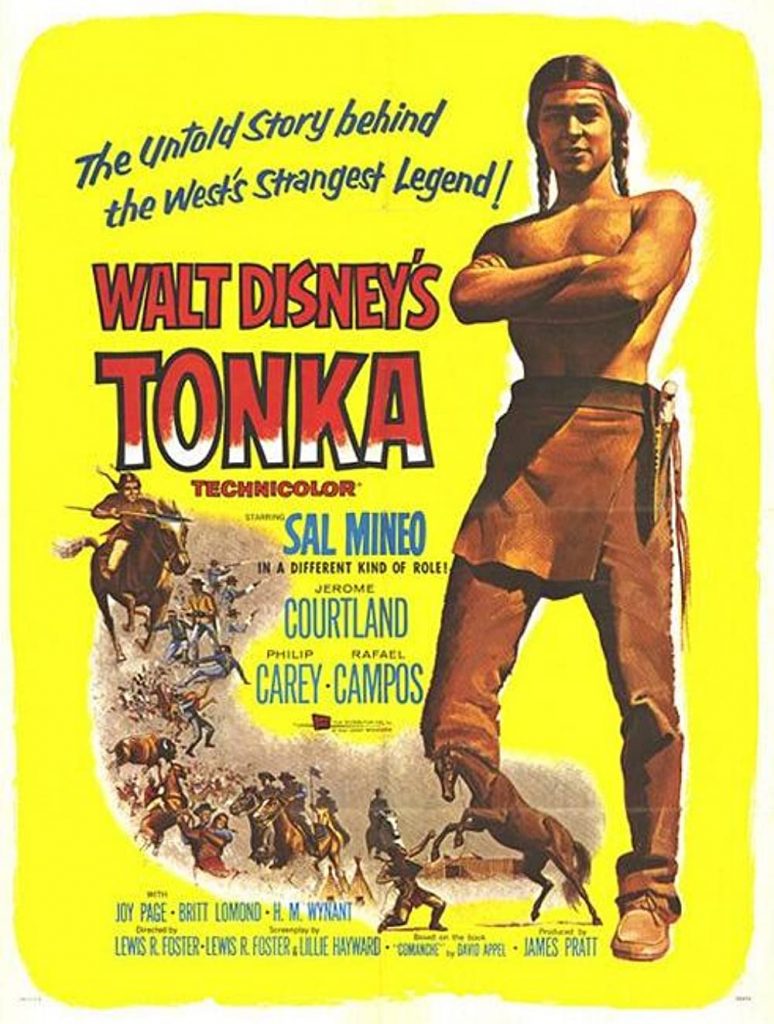

Cassavetes married Gena Rowlands in 1954, a talented young actress he had met while both attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. If not his muse, Rowlands would most certainly become Cassavetes’ most ardent supporter and constant collaborator as he moved from actor to filmmaker over the years that followed. Soon after, his career picked up traction with back-to-back turns in a pair of B-movies. Cassavetes played an accomplice of Vince Edwards in the home invasion thriller “The Night Holds Terror” (1955), then a juvenile delinquent opposite Sal Mineo in director Don Siegel’s “Crime in the Streets” (1956). Using his newfound name recognition as a draw, he taught acting classes for a time in 1956 at an experimental drama workshop with long-time friend and actor Burt Lane. By all accounts, the mercurial Cassavetes’ contribution and attendance was erratic and unreliable, to say the least. Part of the problem was that he was becoming more and more in demand, with larger roles in relatively prominent films coming his way. A case in point was Cassavetes’ starring role opposite Sidney Poitier in Martin Ritt’s waterfront drama “Edge of the City” (1957), a ground-breaking portrait of interracial bonding in the face of violent intolerance. Another factor pulling Cassavetes away from his duties at the drama workshop was his decision to produce, write and direct a film of his own. It would be an arduous journey, filled with optimistic starts and heartbreaking stops over the three years that followed.

Desperately in need of cash to complete his unfinished film, Cassavetes reluctantly took on his one and only starring role in a television series. As “Johnny Staccato” (NBC, 1959-1960), he played a piano-playing private eye working the jazz-soaked haunts of New York’s Greenwich Village. Although well-received by several critics, the stylized crime drama was canceled within its first season. Cassavetes was glad to get out of the commitment. Still, the experience had not been a complete loss. In addition to securing the money needed to complete his own project, it did provide the actor with some of his first official directorial credits. Begun in 1957, reshot almost entirely two years later, and largely inspired by his experience on “Edge of the City,” Cassavetes at last unveiled his feature directorial debut, “Shadows” (1959). Shot on 16-mm on location in New York in a loose, cinéma vérité style, “Shadows” not only marked a turning point in Cassavetes’ career, but began a new era in American film. The story of racial identity and relationships within a small African-American family, “Shadows” was short on plot or traditional cinematic conventions. Rather, it was an exploration of character and the human condition in a highly collaborative effort between Cassavetes and his ensemble. While the film garnered scant attention at the box office and more than its share of detractors, it did win a number of awards at the Venice International Film Festival. “Shadows” also brought the filmmaker to the attention of several studio executives, always on the look out for new talent.

Given a modest budget by Paramount Pictures, Cassavetes was given the green light to write, direct and produce “Too Late Blues” (1961), a drama about a jazz trumpeter (Bobby Darin) struggling with concerns over career, artistic integrity and a beautiful young singer (Stella Stevens). Though he endeavored to make a personal, low-budget film, the novice director soon learned that his artistic intentions and the studio’s concerns were not compatible. Savaged by most critics, “Too Late Blues” proved a valuable early lesson for Cassavetes in his future dealings with the establishment. He gave it another try after being convinced by director-producer Stanley Kramer to take the helm of a project at United Artists. A social-drama about conflicting ideologies at an institution for the mentally disabled, “A Child Is Waiting” (1962) starred Burt Lancaster and Judy Garland. From the beginning, it was clear that Cassavetes and Kramer – much like the conflict between Lancaster’s and Garland’s characters – had differing opinions on the material. As soon as shooting was completed, Kramer dismissed his young director and edited the picture to fit his vision. The frustrating experience and resulting film were bitter disappointments for Cassavetes, who vowed never to direct under studio constraints again.

Having relocated with Rowlands to Los Angeles in the early 1960s, Cassavetes took on work in several mainstream film and television projects, primarily for financial reasons, although the efforts did yield several of his more memorable acting roles. He played the intended target of “The Killers” (1964), based on the story by Ernest Hemingway. Later, Cassavetes gained considerable attention for his Academy Award-nominated turn in the man-on-a-mission classic “The Dirty Dozen” (1967), as well as his convincing performance as Mia Farrow’s narcissistic actor-husband in director Roman Polanski’s horror masterpiece, “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968). All of the acting paychecks ultimately led to Cassavetes’ second independently-produced film, “Faces” (1968). Cut from the same cloth as “Shadows,” the film featured many of Cassavetes’ de facto stock company – Rowlands and character actor Seymour Cassel among them – and was filmed in a similarly collaborative manner that allowed the actors to shape both their characters and the ultimate direction of the film. An examination of the disintegration of an unsatisfying marriage and an indictment of the shallowness of modern America, “Faces” earned Oscar nominations for both Cassel and actress Lynn Carlin, in addition to one for Cassavetes for original screenplay. It also cemented Cassavetes’ growing reputation as one of the more unique voices in American cinema.

Cassavetes’ next directorial effort was “Husbands” (1970), a story about three married men (Cassavetes, Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara) who embark on a wild jaunt to London while struggling to cope with the sudden death of a close friend. “Husbands” proved deeply divisive among critics, some of whom declared it one of the very best films of the year, while others dismissed it as a tedious failure. Cassavetes, however, was not interested in critical consensus, but in provoking discussion in his pursuit of artistic truth. In that endeavor, he succeeded. Having established momentum with his work as a director, he quickly followed with “Minnie and Moskowitz” (1971), a romantic duet starring Rowlands as a disillusioned museum curator pursued by Cassel’s smitten parking lot attendant character. Financed with his own money, in addition to funds borrowed from Peter Falk, “A Woman Under the Influence” (1974) was a devastating portrait of a loving wife (Rowlands) whose increasingly erratic behavior forces her concerned husband (Falk) to contemplate having her committed. Unable to find a major distributor for the finished film, Cassavetes formed Faces International, which helped book the movie in any art house or film festival he could. Word of mouth built and soon “A Woman Under the Influence” was garnering near universal acclaim, eventually going on to earn Rowlands and director Cassavetes Oscar nominations. In the years that followed, many would see the film as the creative and critical peak of the filmmaker’s career.

Taking inspiration from friend and supporter Martin Scorsese, Cassavetes wrote and directed the crime drama “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie” (1976). Ben Gazzara starred as Cosmo Vittelli, a strip club owner and chronic gambler coerced into performing a mob hit. Gritty and gripping, the film performed poorly upon its initial release, only to be regarded as one of the filmmaker’s best efforts years later. In a rare acting gig that was neither done for money nor as an appearance in one of his own films, Cassavetes co-starred with Falk in first-time director Elaine May’s “Mikey and Nicky” (1976). A buddy movie in which ne’er-do-well Nicky (Cassavetes) enlists the help of his pal Mikey (Falk) in escaping the wrath of the mob, it became infamous for a battle between May and Paramount that ended with the over-budget film being pulled from theaters and shelved for a decade. Cassavetes went behind the camera once more to helm the psychological drama “Opening Night” (1977), in which Rowlands essayed the emotional collapse of a Broadway actress battling loneliness, alcoholism and the fear of growing old. For her emotionally raw performance, Rowlands won the Best Actress Award at the 28th Berlin International Film Festival.

One of Cassavetes’ more accessible films was, without a doubt, the crime-drama “Gloria” (1980). The closest Cassavetes would ever come to directing a traditional action movie, the film again starred Rowlands as the eponymous, tough-as-nails heroine, who becomes the unexpected protector of a young boy targeted by the mob. A rare commercial hit for Cassavetes, it earned Rowlands another Oscar nomination, served as the inspiration for several similarly themed films, and spawned a literal remake starring Sharon Stone nearly two decades later. Although most of his acting jobs during this period were strictly as a hired gun, Cassavetes appeared to enjoy himself in writer-director Paul Mazursky’s updating of Shakespeare’s “Tempest” (1982), playing the Prospero role with manic relish. His 11th film as a director was the drama “Love Streams” (1984), an intimate examination of the enduring love between middle-aged siblings (Cassavetes and Rowlands) whose bond endures, even as their lives crumble around them. “Love Streams” would also be considered Cassavetes’ last truly personal film by many admirers in the years that followed. Taken over by Cassavetes from the film’s writer and original director, the lackluster comedy “Big Trouble” (1986) was a film Cassavetes essentially washed his hands of after the studio began making changes he disagreed with.

Just prior to starting production on “Love Streams,” Cassavetes had been diagnosed with severe cirrhosis of the liver and given six months to life. In true Cassavetes form, he defied expectations and lived years past his predicted demise. Nonetheless, the disease was taking its toll on him and by the late-1980s, Cassavetes’ condition had grown extremely fragile. Refusing to give in, he managed to write and produce a play in Los Angeles and was working on a film project with actor Sean Penn, tentatively titled “DeLovely,” just prior to his death on Feb. 3, 1989. John Cassavetes was 59 years old. In addition to his remarkable body of work as a filmmaker and his better known acting roles, Cassavetes’ legacy was furthered by his wife, Rowlands, and the three children he left behind. Nick Cassavetes would become an established filmmaker in his own right, bringing his father’s unfinished final project to light as he had intended in the form of the film “She’s So Lovely” (1997), starring Sean Penn. Daughter Alexandra “Xan” Cassavetes directed the acclaimed documentary “Z Channel: A Magnificent Obsession” (2004), while youngest daughter Zoe wrote and directed the romantic drama “Broken English” (2007), which featured a supporting turn by Rowlands.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.