Marc Platt was born in 1913 in Pasadena, California. He was a brilliant dancer and his film debut was in 1945 in “Tonight and Every Night”. He was also featured in “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers” and “Oklahoma”

His “Guardian” obituary:

Marc Platt was one of the first Americans to join the Ballets Russes, and at the time of his death, aged 100, among the very last survivors. Tall and loose-limbed, with red hair and freckles, he must have seemed an unlikely addition to the ranks of the largely Russian company. But when Michel Fokine saw Platoff – as he had been hastily renamed – playing the role of Dodon, the archetypal foolish tsar in his ballet Le Coq d’Or, the choreographer exclaimed: “I didn’t think anyone could be more Russian.”

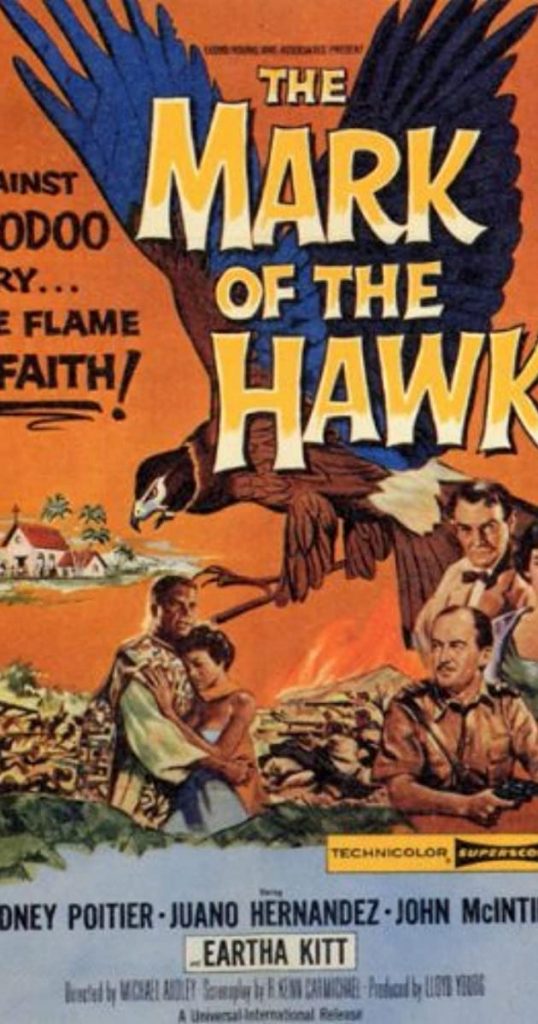

In 1943, Platt created the leading role of Curly in the dream ballet sequence of the Broadway hit Oklahoma!, and he also appeared as a minor character in the 1955 film version of the show. His two best-known film roles, however, were as brother Daniel Pontipee in the musical Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) and in the Rita Hayworth film Tonight and Every Night (1945). In the latter, Platt is shown auditioning for a theatre similar to the Windmill in London. Having failed to bring music with him, he dances to music from the radio, changing styles as the theatre owner switches stations, moving instantly and effortlessly between classical, tap, swing and flamenco in a tour de force.

The son of a French violinist who had moved to the US and a soprano singer, Marcel Le Plat was born in Pasadena, California. The family travelled widely but eventually settled in Seattle, where Marcel studied first at the Cornish school (now Cornish College of the Arts) and then for eight years with the dancer and trainer Mary Ann Wells. It was Wells who, in 1935, arranged an audition for him with Wassily de Basil and Léonide Massine, respectively director and choreographer of the Ballets Russes. Once accepted, he immediately joined the company on its tour, making his stage debut a few days later.

By Platt’s own account, the occasion was little short of a disaster. He was taller than any of the troupe’s other men, and once he was on stage his ill-fitting costume began to fall apart. Worse was to come with the last ballet of the evening, the Polovtsian dances from Prince Igor. Equipped like all his fellow dancers with a genuine bow, crossing the stage at full speed he mistakenly turned right instead of left and caught his weapon in that of his neighbour, thus causing a major pileup of warriors. “What you were trying to do? Kill everybody?” hissed one of his fellow dancers, adding, “This is ballet. Not war.”

Platt soon found his place in the company, however, and when Massine broke away to form his own troupe in 1938, Platt was one of the artists invited to join it. Later that year, Massine choreographed his Beethoven ballet, Seventh Symphony, which Platt later recalled as giving him “the best role I ever had. I danced my fool head off.” He also created the part of the Devil in Frederick Ashton’s Devil’s Holiday, sadly never seen outside the US and now largely lost.

That same season saw Platt’s first attempt at choreography. Ghost Town had an American theme and a score by Richard Rodgers. It proved a disappointment, but his fellow dancer Frederic Franklin attributed at least part of the blame to Rodgers, who refused to alter his score to suit the scenario.

Platt left the company in 1942, having risen to the rank of soloist and drawn praise for his “superb character work”. But conditions were hard, the pay was poor and Platt now had a family to support, having married a fellow dancer, Eleanor Marra, with whom he had a son. At this time he abandoned his Russianised name, becoming Marc Platt.

In 1962, he became director of the ballet at Radio City Music Hall, a position he held for eight years before moving with his second wife, Jean Goodall – also a dancer – to Fort Myers, Florida, where together they opened a dance school. (His first marriage had ended in divorce.) Goodall died in 1994 and Platt returned to California to be nearer his family. Once settled, he took great interest in dance in the Bay area, guesting with several companies and always happy to watch rehearsals, coach and provide feedback. “Always do what you love as long as you can,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle in an interview published when he was 100.

When, in June 2000, a reunion of all the surviving Ballets Russes veterans was organised, Platt was among the attenders. He also played a prominent part in the subsequent 2005 documentary, his modesty, easy charm and sharp intelligence still very much in evidence.

Platt is survived by the son of his first marriage, the son and daughter of his second, and a grandchild.

• Marc Platt (Marcel Emile Gaston Le Plat), dancer, born 2 December 1913; died 29 March 2014

His “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

One of Hollywood’s more high-flying dancers on film, dimpled, robust, fair-haired Marc Platt provided fancy footwork to a handful of “Golden Era” musicals but truly impressed in one vigorous 1950s classic.

Born to a musical family on December 2, 1913 in Pasadena, California as Marcel Emile Gaston LePlat, he was the only child of a French-born concert violinist and a soprano singer. After years on the road, the family finally settled in Seattle, Washington. Following his father’s death, his mother found a job at the Mary Ann Wells’ dancing school while young Marc earned his keep running errands at the dance school. He eventually became a dance student at the school and trained with Wells for eight years who saw great potential in Marc.

It was Wells who arranged an audition for Marc with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo when the touring company arrived in Seattle. The artistic director Léonide Massineaccepted him at $150 a week and changed his name to Marc Platoff in order to maintain the deception that the company was Russian. A highlight was his dancing as the Spirit of Creation in Massine’s legendary piece “Seventh Symphony”. Platt also choreographed during his time there, one piece being Ghost Town (1939), which was set to music byRichard Rodgers. While there he met and married (in 1942) dancer Eleanor Marra. They had one son before divorcing in 1947. Ted Le Plat, born in 1944, became a musician as well as a daytime soap and prime-time TV actor.

Anxious to try New York, Marc left the ballet company in 1942 and moved to the Big Apple where he changed his marquee name to the more Americanized “Marc Platt” and pursued musical parts. Following minor roles in the short run musicals “The Lady Comes Across” (January, 1942) with Joe E. Lewis, Mischa Auer and Gower Champion and “Beat the Band” (October-December, 1942) starring Joan Caulfield, Marc and Kathryn Sergavafound themselves cast in a landmark musical, the Rodgers and Hammerstein rural classic “Oklahoma!” Choreographer Agnes de Mille showcased them in the ground-breaking extended dream sequence roles of (Dream) Curly and (Dream) Laurey. Platt stayed with the show for a year but finally left after Columbia Pictures signed him to a film contract.

Aside from a couple of short musical films, he made his movie feature debut with a featured role as Tommy in Tonight and Every Night (1945) starring Rita Hayworth. From there he appeared in the Sid Caesar vehicle Tars and Spars (1946) and back with Rita Hayworth in Down to Earth (1947). Columbia tried Marc out as a leading man in one of their second-string musicals When a Girl’s Beautiful (1947) opposite Adele Jergens andPatricia Barry but did not make a great impression. Featured again in the non-musical adventure The Swordsman (1948) starring Ellen Drew and Larry Parks and the Italian drama _Addio Mimi! (1949) based on Puccini’s “La Boheme,” Marc’s film career dissipated.

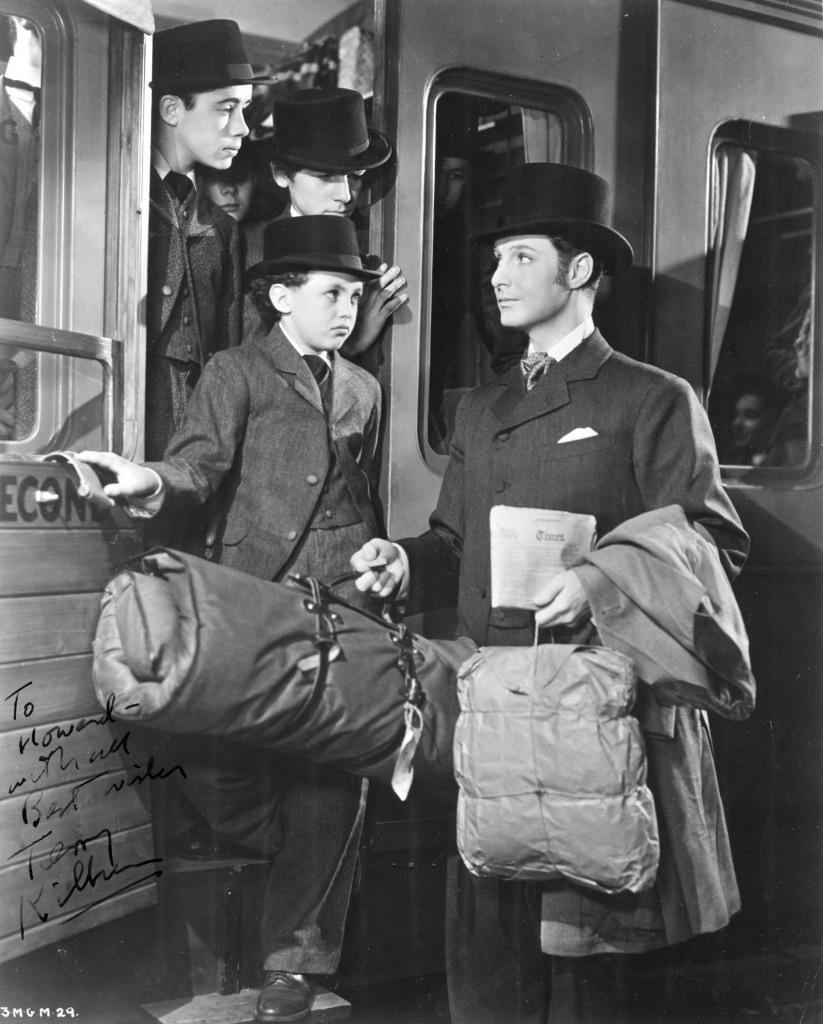

After appearing on occasional TV variety shows such as “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “The Colgate Comedy Hour” and following a single return to Broadway in the musical “Maggie” (1953, Platt returned to film again after a five-year absence but when he finally did, he made a superb impression as one of Howard Keel‘s uncouth but vigorously agile woodsman brothers (Daniel) in MGM’s Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954). The film still stands as one of the most impressive dancing pieces of the “Golden Age” of musicals. He followed this with a minor dancing role (it was James Mitchell who played Dream Curly here) in the film version of Oklahoma! (1955).

When the musical film lost favor in the late 1950’s, Marc finished off the decade focusing on straight dramatic roles on TV with roles in such rugged series as “Sky King,” “Wyatt Earp” and “Dante”. By the 1960s Marc had taken off his dance shoes and turned director of the ballet company at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. He and his second wife, Jean Goodall, whom he married back in 1951 and had two children (Donna, Michael), also ran a dance studio of their own. Following this they left New York and moved to Fort Myers, Florida where they set up a new dance school.

Marc moved to Northern California to be near family following his wife’s death in 1994 and occasionally appeared at the Marin Dance Theatre in San Rafael. One of his last performances was a non-dancing part in “Sophie and the Enchanted Toyshop” at age 89. In 2000, Marc was presented with the Nijinsky Award at the Ballets Russe’s Reunion. He appeared in the 2005 documentary Ballets Russes (2005). Platt died at the age of 100 at a hospice in San Rafael from complications of pneumonia. He was survived by his three children.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net