Independent obituary in 1998:

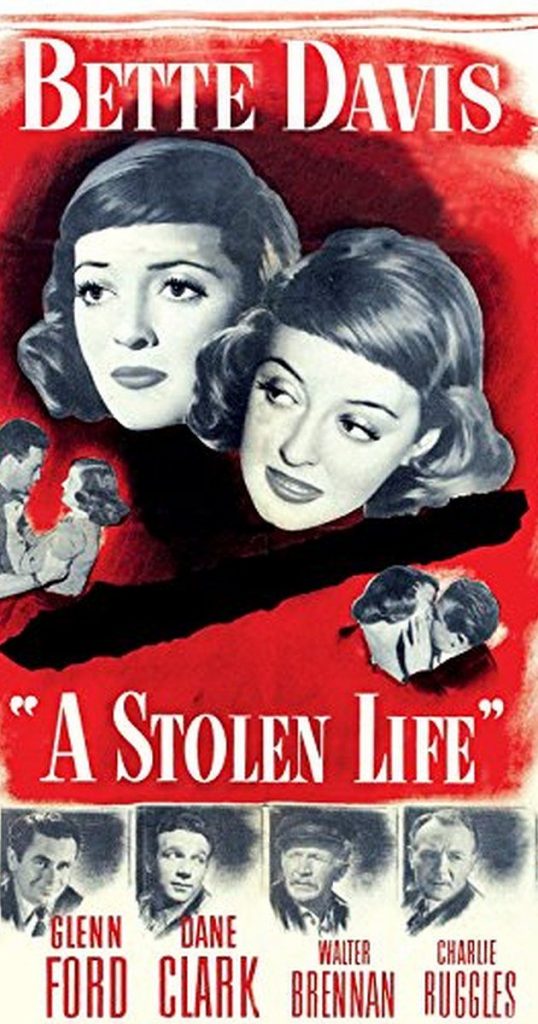

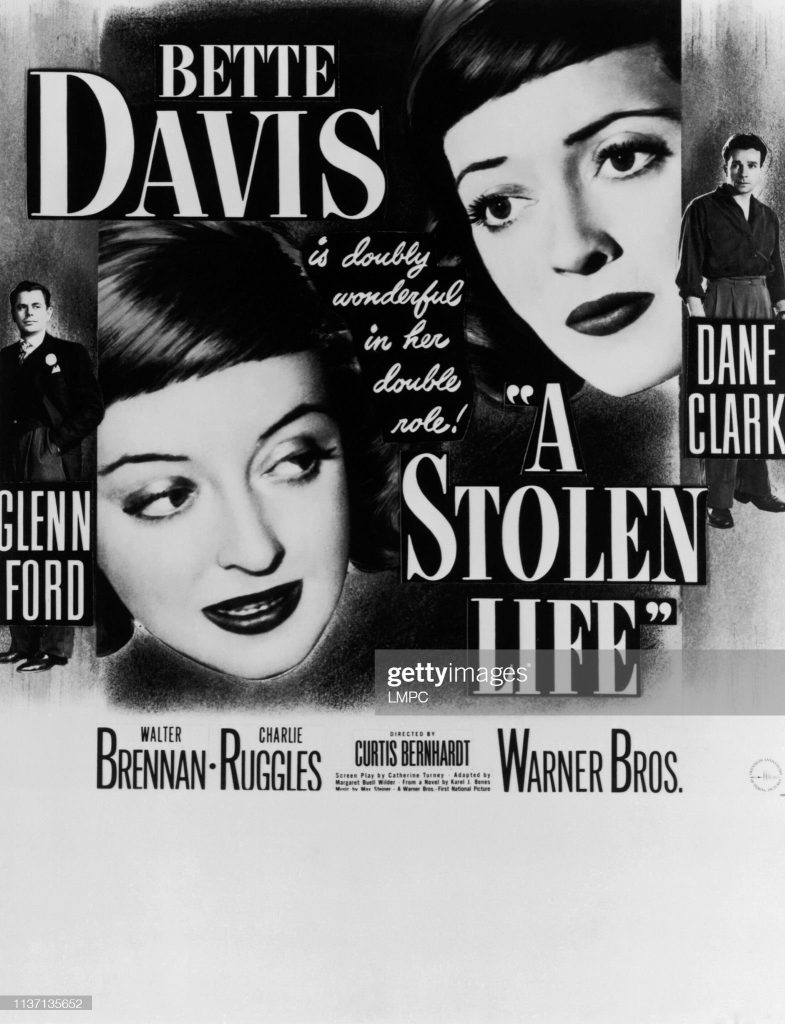

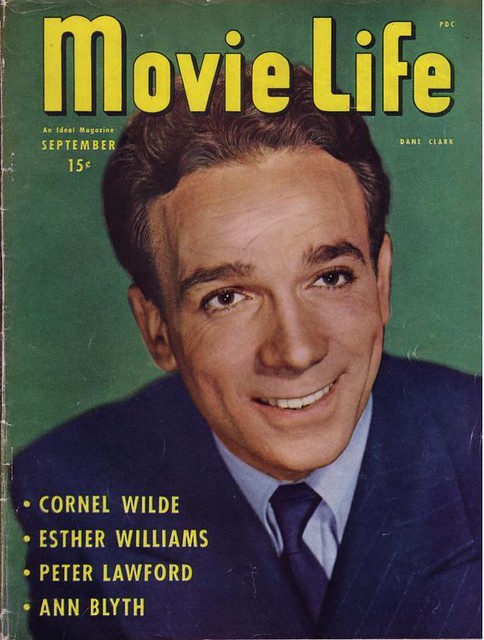

FEW ACTORS were more effective at portraying belligerent, chip- on-their-shoulder characters than Dane Clark. Small in stature, but tough and wiry, he was frequently compared to John Garfield, one of the top stars at the same studio, Warners, but Clark, though popular with cinemagoers in the Forties, never achieved similar stardom. His pugnacious rebels created less empathy than Garfield’s and sometimes (as in his overdrawn anarchic painter of A Stolen Life) upset a film’s balance in their ferocity.

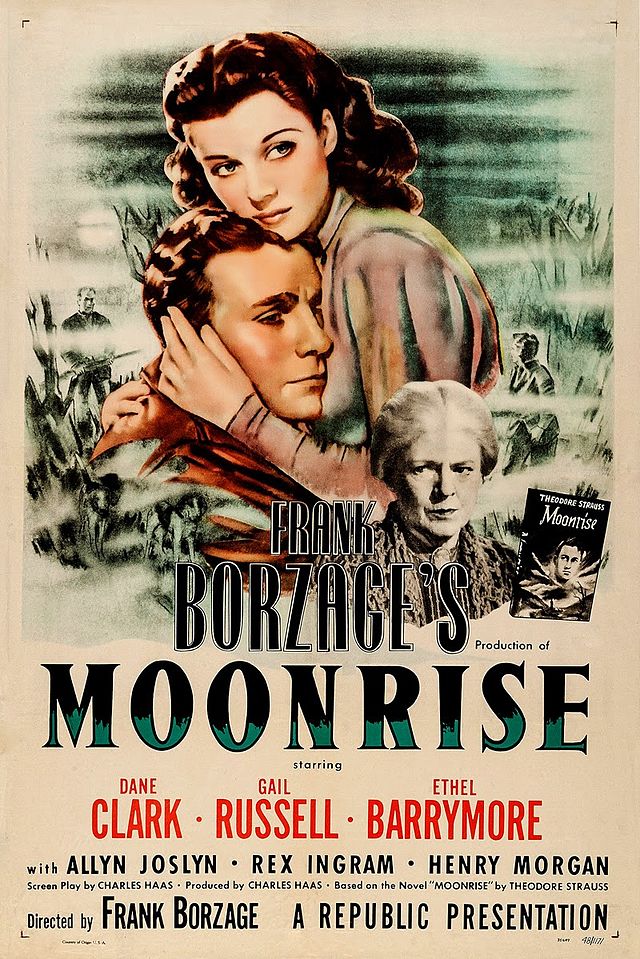

The actor’s intensity was both his strength and his weakness. Though he graduated to leading roles at the studio, his best chance came when he was loaned to Republic to star in Frank Borzage’s Moonrise, a moody piece in which Clark was ideally cast as a hot-tempered outsider whose father was hanged for murder.

Born Bernard Zanville in 1913 in Brooklyn, New York, he was a fine athlete and was given the opportunity to become a baseball player, but chose higher education instead. He received a BA from Cornell University and a law degree from St John’s University, New York, but the Depression limited his opportunities and he worked as a labourer, boxer and model before turning to writing for radio.

This led to acting, and he made his Broadway debut (as Bernard Zanville) in Friedrich Woolf’s Sailors of Catarro (1934), produced by the leftist Theatre Union. George Tobias (later also a contract player at Warners) was in the cast and he and Clark were among those arrested when some of the company joined Communist pickets demonstrating against Orbach’s department store. Though the matinee was cancelled, the actors were bailed out in time for the evening performance.

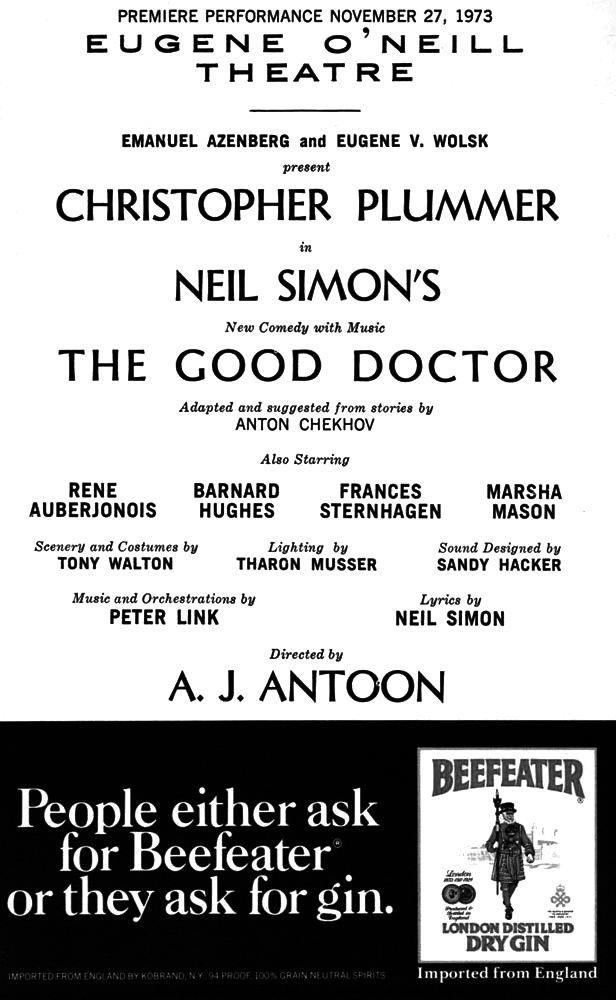

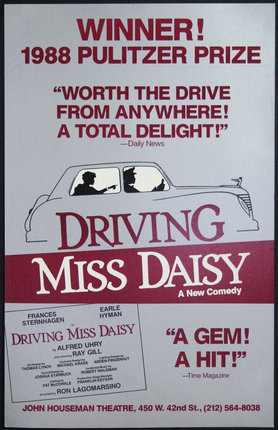

Clark was next in Panic (1935), which ran for only three performances but was described by one critic as “the outstanding critical failure of the year”. An anti-capitalist blank-verse tragedy that attempted to account for the national bank calamity of 1933 in terms of Greek drama, it is considered an important part of theatrical history for several reasons – it was the first play by the poet Archibald MacLeish, it starred the 19-year-old Orson Welles, its producers included John Houseman and Virgil Thomson, and the Greek-style chorus was choreographed by Martha Graham.

Clark then joined the socially conscious Group Theatre and acted in a highly praised Clifford Odets double-bill, the anti-Nazi Till The Day I Die and the radical Waiting for Lefty (1935), in which the auditorium was assumed to be the meeting hall for a group of taxi drivers at a union meeting, with the audience the potential strikers and actors spotted throughout the house to increase the feeling of audience participation.

Clark’s last 1935 show was the most successful, Sidney Kingley’s Dead End, about the deleterious effects of New York’s slums, which ran for two years. Clark then toured in several plays, including the Group Theatre’s biggest success, Odets’ Golden Boy, until being called to Hollywood in 1941 to act in promotional films being made by the US Army.

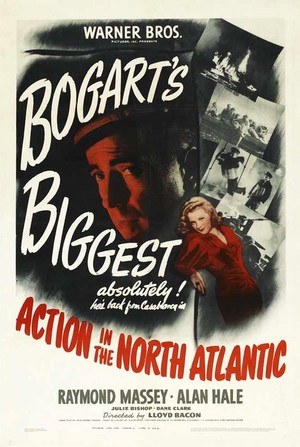

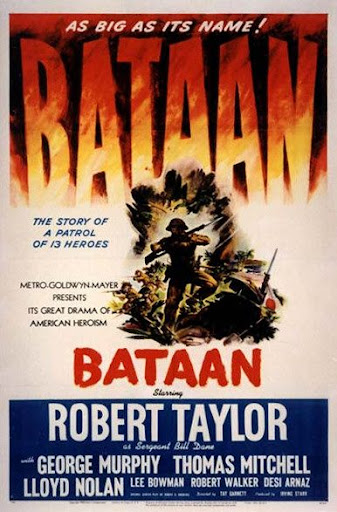

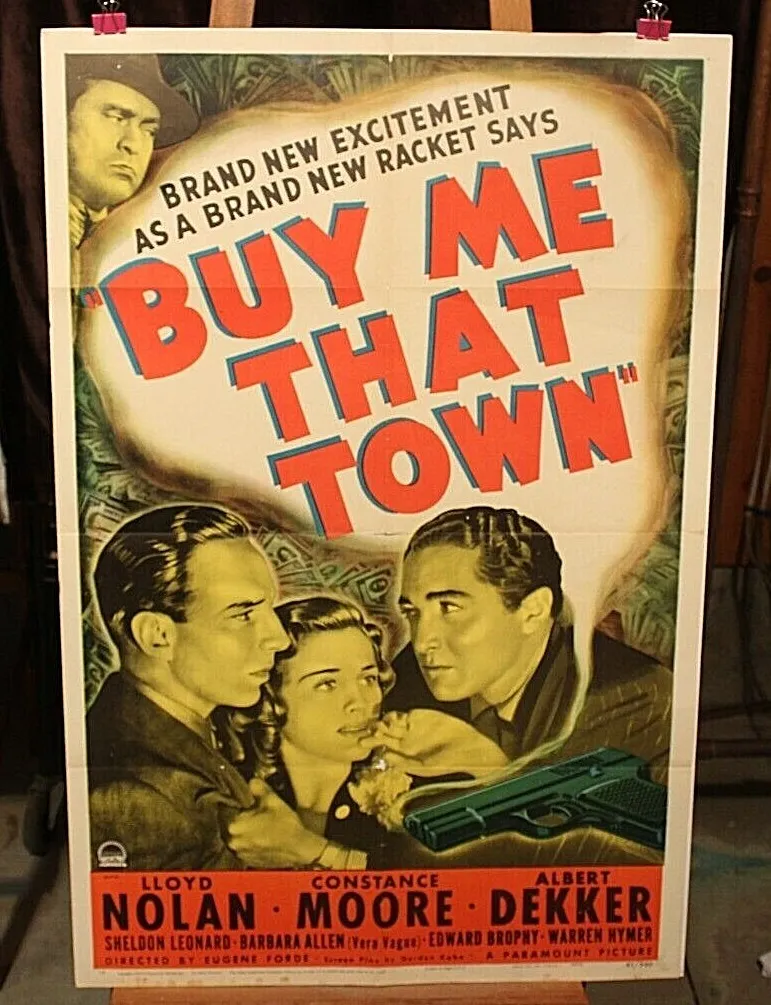

Bit parts in movies followed, including The Glass Key, Wake Island and Pride of the Yankees (all 1942), and at Warners the Bogart war film Action in the North Atlantic (1943).

Warners then offered him a contract, and with the new name of Dane Clark he was given a featured role in Destination Tokyo (1943), the first of two films he made with Garfield (who was also a graduate of the Group Theatre). The story of a submarine crew on combat duty featured Clark as Tin Can, most aggressive of the crew members.

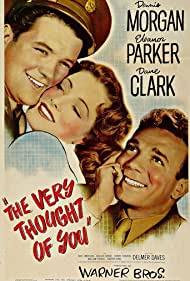

Clark then settled into a run of girl-chasing “best buddy” roles, portraying the soldier friend of Dennis Morgan in The Very Thought of You (1944), Robert Hutton’s soldier pal in Hollywood Canteen (1944), and a wounded soldier who befriends a blinded marine (Garfield) at a military hospital in Pride of the Marines (1945). His role in the all-star Hollywood Canteen is remembered for the moment when he says to the girl with whom he is dancing, “You know, you’re a dead ringer for Joan Crawford.” When she replies, “Don’t look now, but I am Joan Crawford”, Clark promptly faints.

He began to tire of such typecasting, though, and had the first of several battles with the studio head Jack Warner for better roles and more pay. “They were always giving me lines like `You woman, you’,” he said later. “They had me as a teenage soldier back from the Pacific or some place. In The Very Thought of You I had to bark like a dog when I saw a girl. I ask you, how can you be subtle – how can you underplay when you’re making sounds like a dog?”

After A Stolen Life (1946), in which as a consistently bad- tempered painter he woos Bette Davis with the line, “Man eats woman and woman eats man; that’s basic”, he was given his first starring role in Her Kind of Man (1946), a half-hearted attempt by the studio to recapture the glory of their earlier gangster films, in which Clark, as a newspaper man, gets Janis Paige, a night-club singer, out of the clutches of the gangster Zachary Scott. Whiplash (1948) was similar, only this time Clark was a painter rescuing Alexis Smith from Scott.

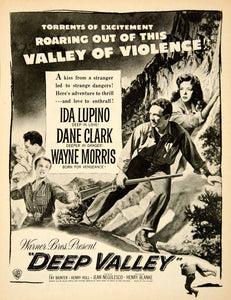

Before this, Clark had his best role at Warners, as a bitter convict who escapes from a chain-gang and is sheltered by an introverted farm girl (Ida Lupino) in Deep Valley (1947). Because of a set builders’ strike at the studio, the whole film was made on location in Big Sur and Big Bear, California, and its director Jean Negulesco later recounted that the long period away from the studio led Clark and Lupino to have a passionate affair which, he said, ended as quickly as it began once the couple returned to their normal life style.

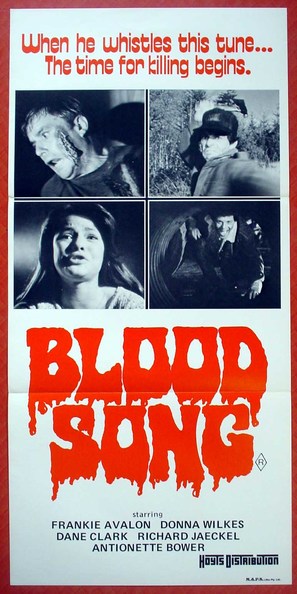

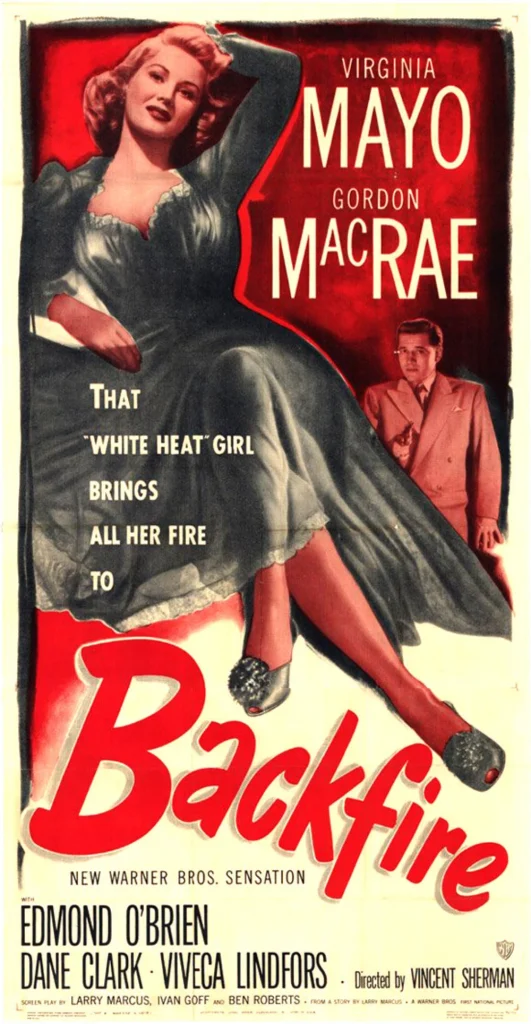

Clark was then borrowed by Republic for Moonrise (1948). The story of a social outcast on the run after an accidental killing was treated with lyrical romanticism, and the offbeat teaming of the grim Clark and ethereal Gail Russell as his girlfriend gave the film extra piquancy. Clark finished his Warner contract with two minor films, Barricade (1950), in which he beat Raymond Massey, a sadistic mine-owner, to death, and a mystery story, Backfire (1950).

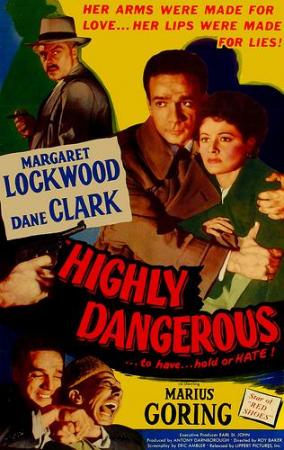

The following year Clark came to England to star with Margaret Lockwood in Roy Baker’s comedy-thriller Highly Dangerous. In this fanciful tale of an entomologist (Lockwood) on a government spy assignment who is given a truth drug by the enemy under which she imagines herself as her favourite Dick Barton-like radio character and saves the day with the aid of an American reporter (Clark), the actor revealed an unexpectedly droll sense of humour. In 1954 he co-produced and starred in the story of the Harlem Globetrotters, Go Man Go.

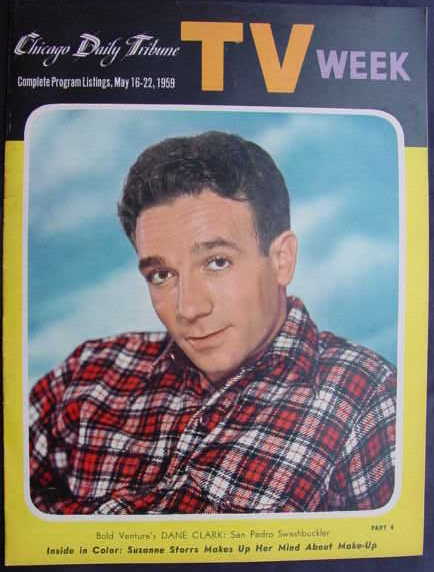

A consistent performer on radio throughout his career, Clark was also a television pioneer, appearing in a Chevrolet Tele-Theatre episode in 1949. He went on to appear in dozens of television shows and starred in two series, Wire Service (1956-57) as a reporter, and Bold Venture (1957), which he described at the time as “about an adventure-bent skipper of a small Caribbean boat-for-hire. Eugene O’Neill this ain’t.”

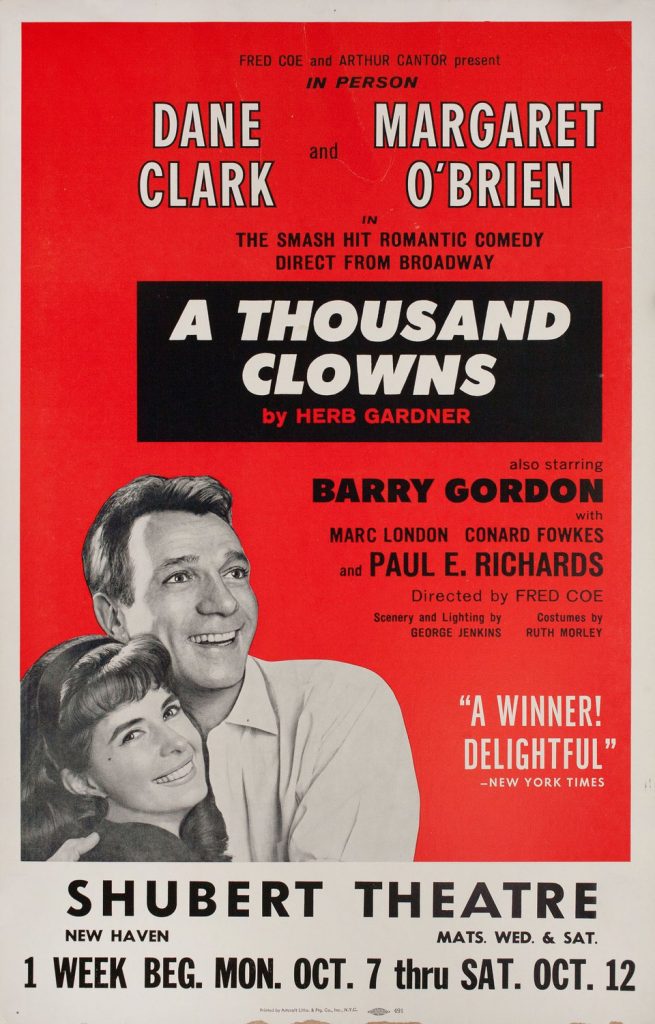

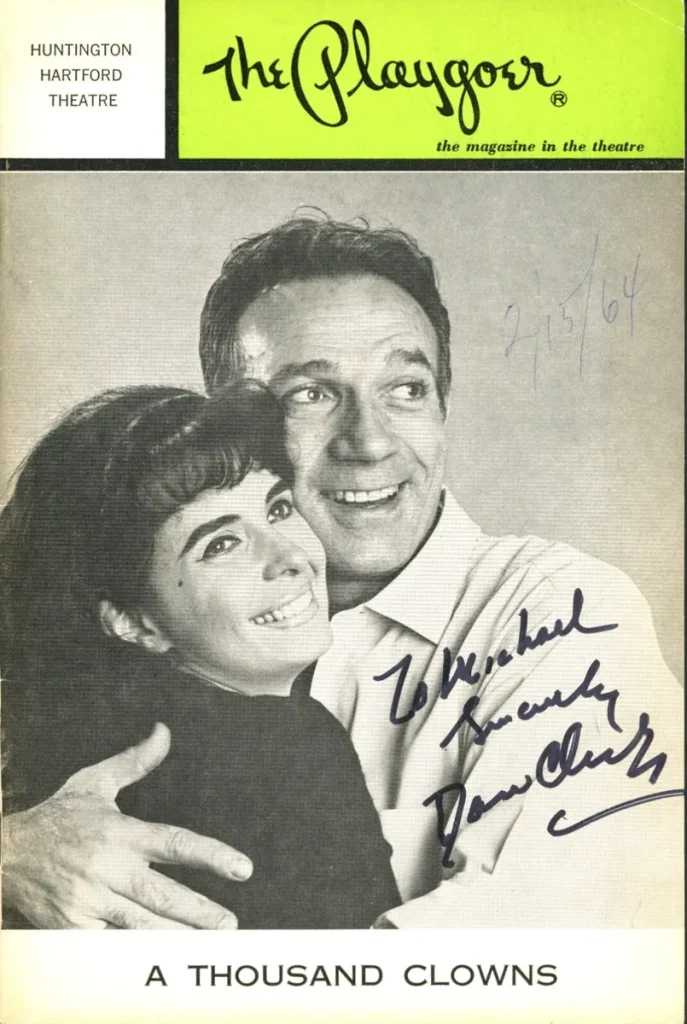

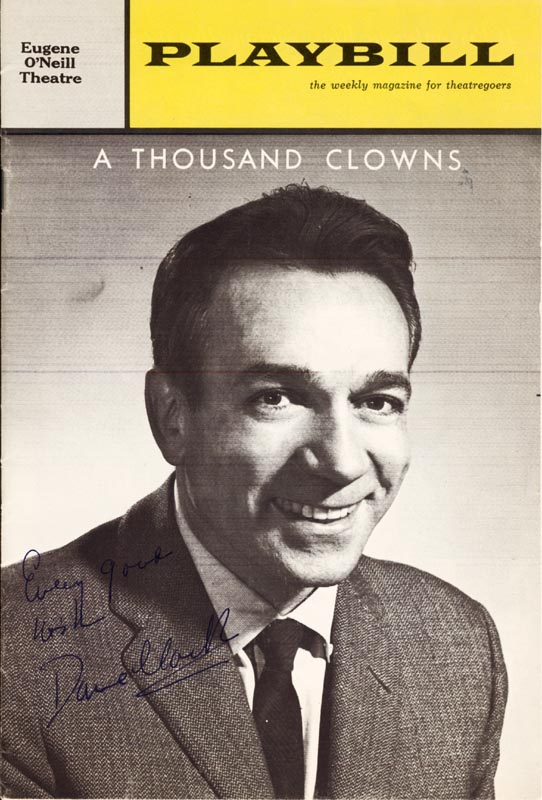

Television movies in which he appeared included Say Goodbye, Maggie Cole (1975), the last film made by Susan Hayward, and from 1974 until 1978 he had a regular role on the series Police Story. Clark returned to Broadway in the Sixties as replacement lead in Tchin Tchin and A Thousand Clowns. Late in that decade his wife of many years, Margot Yoder, died, and in 1972 he married a young stockbroker, Geraldine Frank.

Bernard Zanville (Dane Clark), actor: born New York 18 February 1913; married first Margot Yoder (deceased), second 1972 Geraldine Frank; died Santa Monica, California 11 September 1998

New York Times obituary in 1998:

Dane Clark, the Brooklyn-born actor whose down-to-earth portrayals of tough but appealing soldiers, sailors and pilots in World War II films for Warner Brothers brought him stardom, died on Friday at St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif. He was 85 and lived in Brentwood.

”That was the best break of my life, hooking up with the Warners,” Mr. Clark said in a 1946 interview. ”They don’t go much for the ‘pretty boy’ type there. An average-looking guy like me has a chance to get someplace, to portray people the way they really are, without any frills.

”The only thing I want to do in films is to be Mr. Joe Average as well as I know how. Of course, anyone whose face appears often enough on the screen is bound to have bobby-soxers after him for autographs. But what I really get a kick out of is when cab drivers around New York lean out and yell ”Hi, Brooklyn’ when I walk by. They make me feel I’m putting it across O.K. when I try to be Joe Average.”

Mr. Clark made some 30 films, beginning with ”Sunday Punch” in 1942 and ending with ”Last Rites” in 1988. But he also appeared on Broadway and on the road in a variety of stage roles and performed frequently on television. But he never became as big a star as his friend John Garfield, who suggested he take up acting, or Humphrey Bogart, who, he said, gave him the name Dane Clark.

Mr. Clark’s early credits were under his real name, Bernard Zanville, and it was under that name in the role of a sailor named Johnnie Pulaski that he caught the attention of the critics in the 1943 Warners Brothers feature ”Action in the North Atlantic,” which paid tribute to the heroism of the merchant marine.

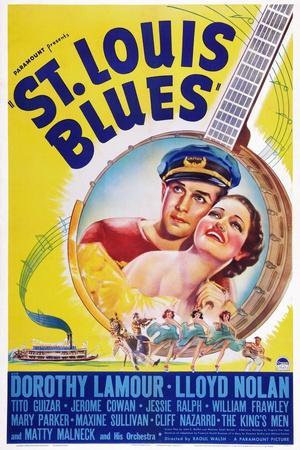

As Bernard Zanville, he appeared in films like ”The Glass Key,” ”Wake Island” and ”The Pride of the Yankees” in 1942, and as Dane Clark he portrayed a sailor aboard a submarine in ”Destination Tokyo” in 1944, a flier in ”God Is My Co-Pilot” in 1945 and a leatherneck in ”Pride of the Marines” that same year.

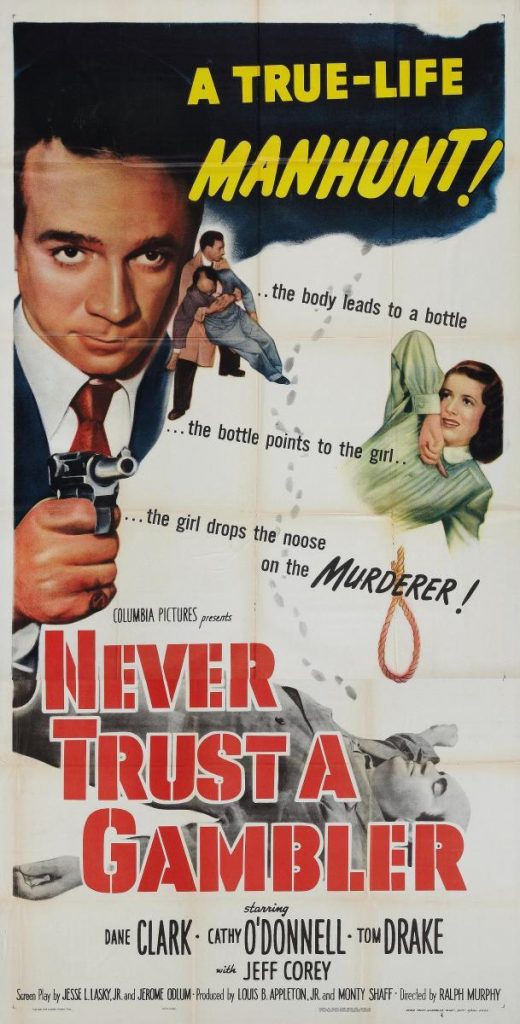

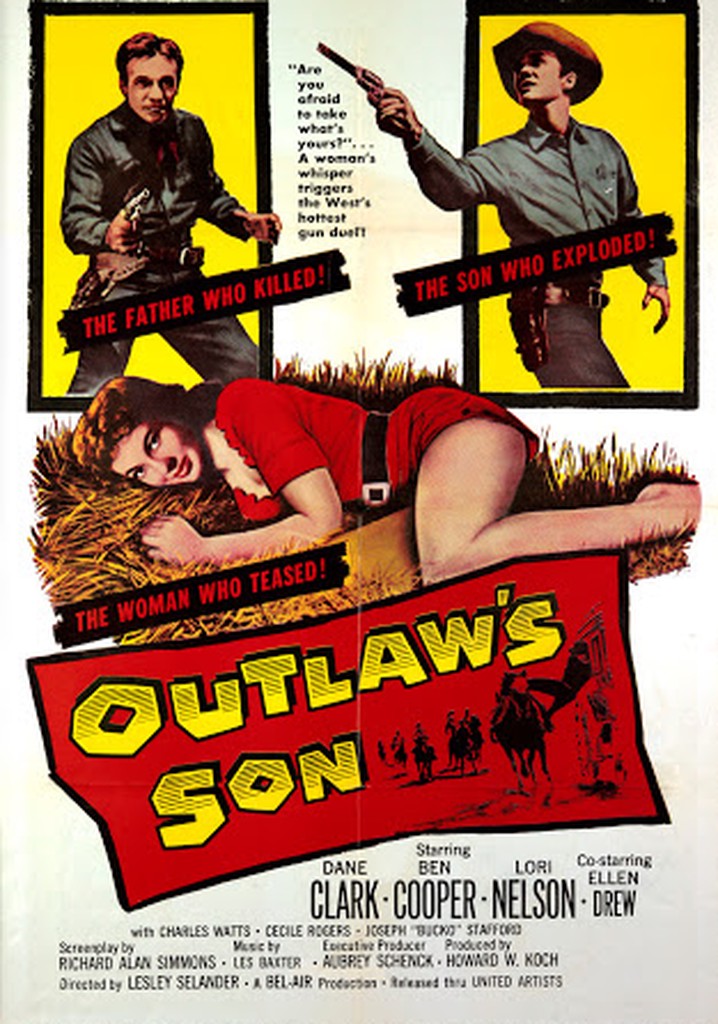

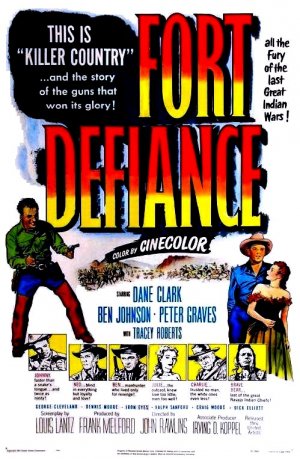

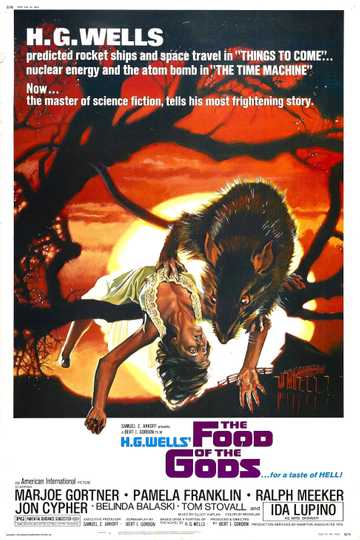

Among his other films were ”Hollywood Canteen” (1944), ”A Stolen Life” (1946), ”Whiplash” (1948), ”Fort Defiance” (1951), ”Never Trust a Gambler” (1951) and ”Outlaw’s Son” (1957). His co-stars were people like Bogart, Garfield, Cary Grant, Bette Davis and Raymond Massey.

Mr. Clark was especially proud of the 1954 film ”Go, Man, Go!,” in which he played Abe Saperstein, the founder of the trailblazing black basketball team the Harlem Globetrotters, because he regarded the film as a forerunner of others that decried racial discrimination and championed civil rights.

Mr. Clark, who was born in Brooklyn on Feb. 18, 1913, was a product of the Great Depression. As a graduate of Cornell University and St. John’s Law School in Brooklyn in the mid-1930’s, he said, he found that lawyers were having as hard a time as anyone else finding work. He drifted into boxing. At 5 foot 10, weighing 162 pounds, the hazel-eyed, brown-haired Mr. Clark soon concluded that he was outmatched and saw no sense in taking beatings. To earn a dollar, he said, he played baseball, labored at construction, worked as a salesman and then, as a sculptor’s model, fell in with what he called an arty set.

”They fascinated me at first,” he said. ”Then suddenly it struck me that their constant snobbish talk about the ‘theatah’ was a little on the phony side. I decided it give it a try myself, just to show them anyone could do it. Before I knew it, I was getting small parts on Broadway, then bigger ones. Then finally I got some good spots in ‘Dead End” and ‘Stage Door’ and finally took over the lead from Wally Ford in ‘Of Mice and Men.’ ” Before long, Mr. Clark decided to try his luck in Hollywood.

Mr. Clark’s first wife, Margot Yoder, a painter and sculptor, died in 1970. He is survived by his wife of 27 years, Geraldine.

”This is a very complex, wondrous business I’m in,” Mr. Clark once said as he reminisced. ”My kicks are my work. I’m miserable when I’m not working.

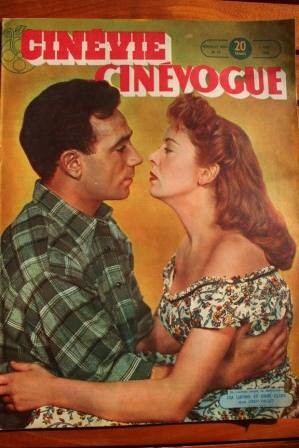

Dane Clark was born in 1912 in Brooklyn, New York. He signed a Warner Brothers contract in 1943 and established himself as a capable leading man of film noir and gritty thrillers. His films include “A Stolen Life” opposite Bette Davis in 1946, “Deep Valley” and “Moonrise” opposite Gail Russell. He died in 1998 at the age of 86.

TCM Overview:

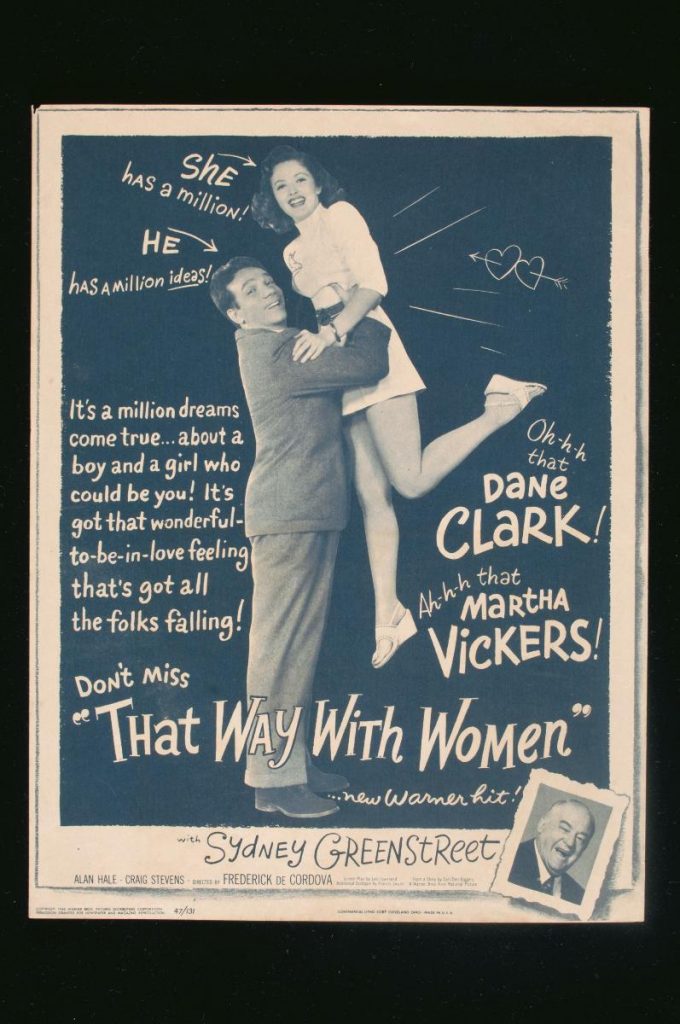

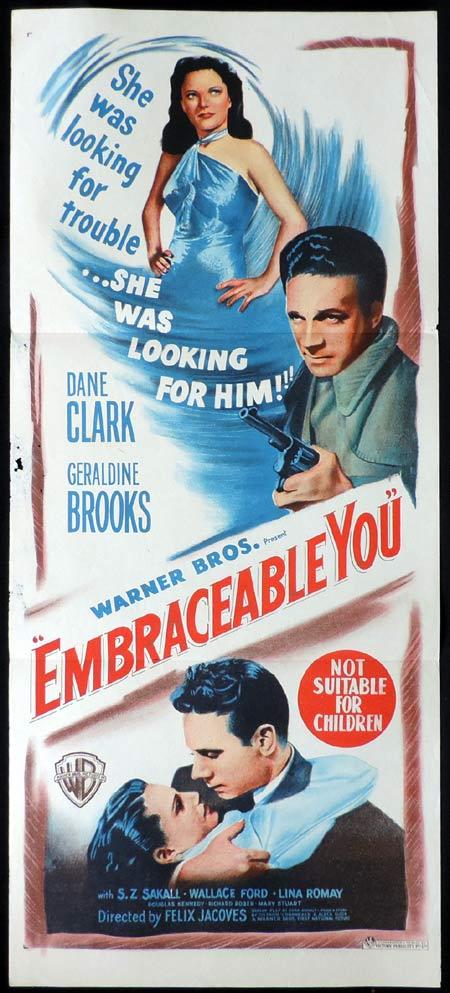

Bernard Zanville was a hard-working young man in New York City struggling to finance his law degree, when he turned to acting on the advice of friend John Garfield. After appearing on stage for several years, including a stint starring alongside Garfield in the original cast of Clifford Odets’ “Waiting for Lefty” (1935), Zanville gave up his dreams of law school and relocated to Hollywood to pursue a movie career. Hooking up with Warner Bros., his name was changed to the more marquee friendly Dane Clark, allegedly by Humphrey Bogart who co-starred with the young actor in what was more or less his star-making performance as merchant marine Johnny Pulaski in 1943’s “Action in the North Atlantic”. That same year, Clark acted alongside Cary Grant and Garfield in “Destination Tokyo” and went on to convincingly play pugnacious soldiers in war-themed pictures for Warners like “God is My Co-Pilot” and “Pride of the Marines” (both 1945). Movies like “Her Kind of Man” (1946), “Deep Valley”, “Embraceable You” and “That Way With Women” (all 1947) featured Clark’s tough guy persona put to new use, now as the dangerous leading man, the misunderstood gangster type who gets involved with a nice girl and changes his ways.

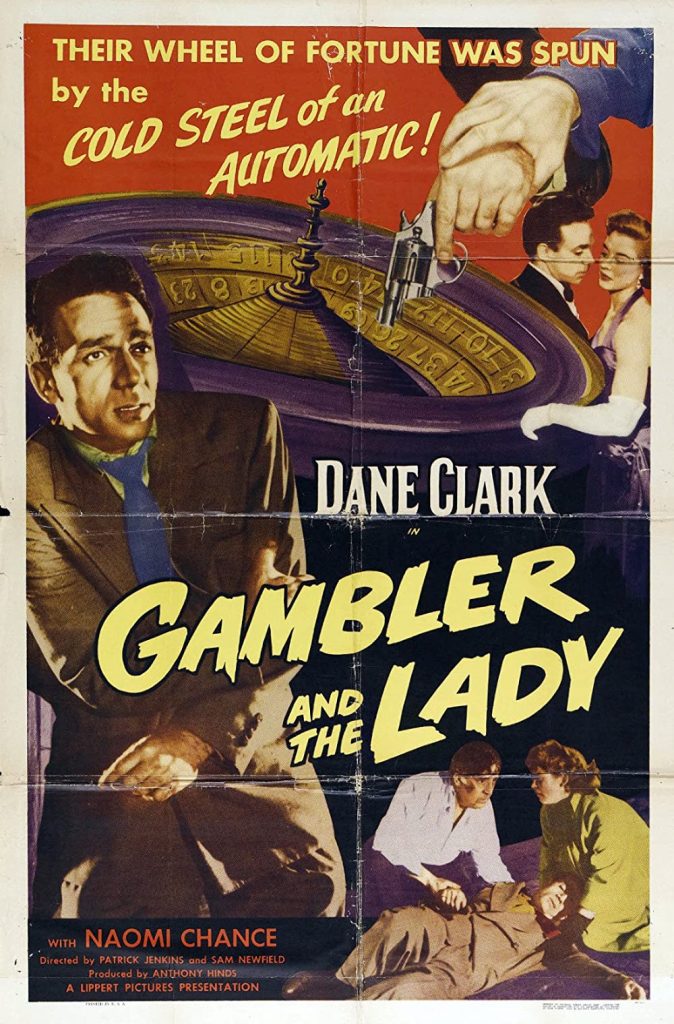

Despite his undeniable talent and magnetism, Clark never took off as a star the way his friend John Garfield did, even after his scene-stealing turn in “Hollywood Canteen” (1944), a performance alongside such notables as Bette Davis, Joan Crawford and Jack Benny. His prolific acting career included starring turns in dozens of films in the 40s and 50s, including a memorable portrayal of Abe Saperstein in “Go, Man, Go!” (1954), the story of the creation of basketball’s famous Harlem Globetrotters. Clark eventually left Hollywood to work on the stage and in features produced overseas. He worked for J Arthur Rank in London, appearing in 1950’s “Highly Dangerous” and 1952’s “The Gambler and the Lady”. In 1968, he starred in the Denmark/US co-production “Dage i Min Fars Hus/Days in My Father’s House”.

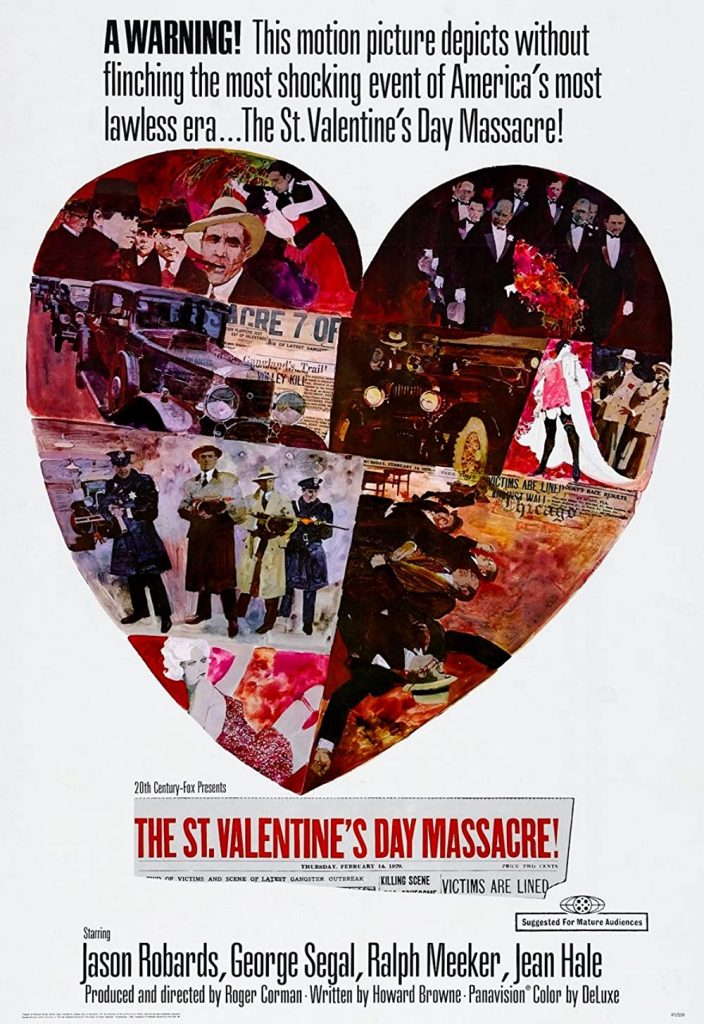

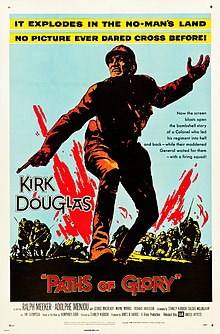

Clark returned to the stage after achieving film success, starring in many Broadway productions (e.g., “A Thousand Clowns” in which he replaced Jason Robards). He was also a frequent presence on the small screen, first appearing in several of the theater anthology programs that were popular in the medium’s early days. Clark made his series debut as legal aid lawyer Richard Adams in the NBC drama “Justice” (1954-56) and headlined the 1959 syndicated series “Bold Venture”. Throughout much of the 60s, 70s and 80s, Clark was a familiar face as a guest performer on shows as varied as “The Twilight Zone”, “I Spy”, “The Mod Squad” and “Murder, She Wrote”. He returned to series work as a police lieutenant in the CBS remake “The New Adventures of Perry Mason” (1973-74). Clark made his last film appearance in 1988’s “Last Rites” starring Tom Berenger. The veteran actor died in 1998, battling cancer.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.