about me

Anyone who knows me is aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been building an autograph collection of my favourite actors’ signed photographs. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I enjoy. I have collected the photographs from the actors themselves, through contacts in the studios and through auctions. I now have over 2,000 photographs in the collection.

My Autograph Collection

I have separated my autograph collection into different categories, which you can see below. Feel free to browse whichever section interests you. Inside, I share not only the autographed photo in my possession, but also information about the actor, including their biography, photos and posters of their movies, and sometimes videos dedicated to them.

Whether you’re drawn to classic Hollywood icons, contemporary superstars, or character actors with a cult following, there’s something in my autograph collection for every movie enthusiast. If you enjoy my blog, don’t hesitate to leave a comment on one of my entries.

Actors Autograph Collections

Blog Categories

BRITISH ACTORS

Collection of Classic Brittish Actors

IRISH ACTORS

Collection of Classic Irish Actors

HOLLYWOOD ACTORS

Collection of Classic Hollywood Actors

EUROPEAN ACTORS

Collection of Classic European Actors

CONTEMPORARY ACTORS

Collection of Classic Contemporary Actors

RECENT POSTS

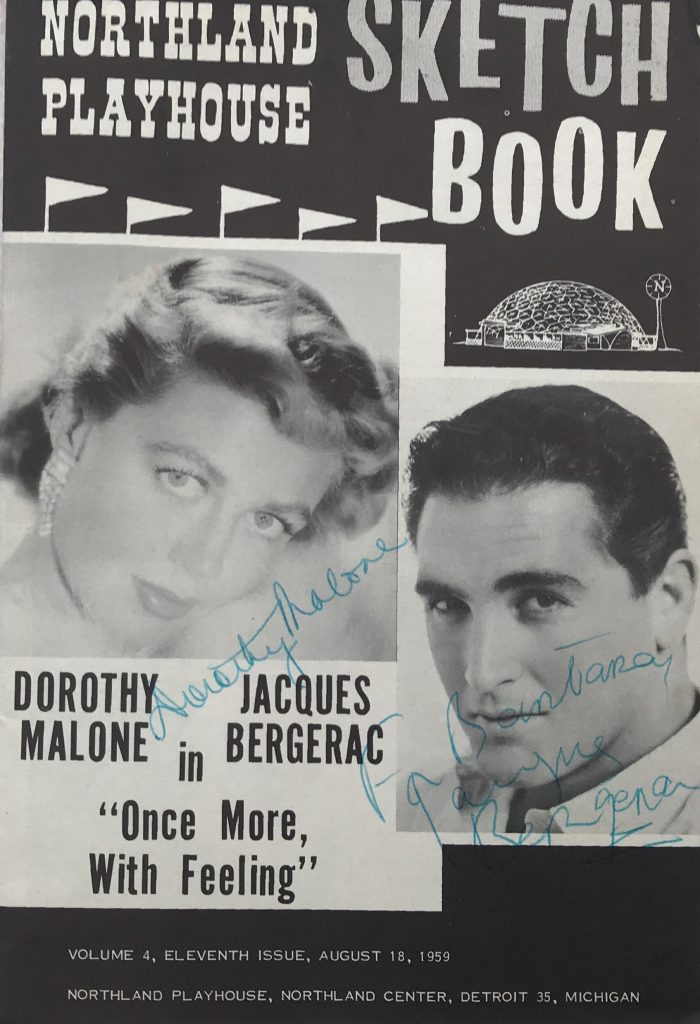

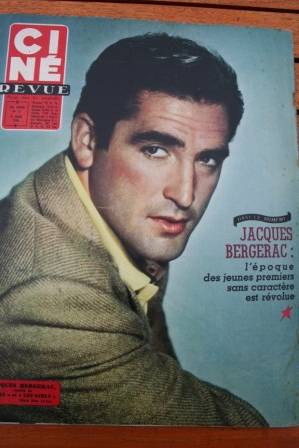

Jacques Bergerac (Wikipedia)

Jacques Bergerac was born in 1927 and was a French actor who later became a business executive with Revlon.

Jacques Bergerac was born in 1927 in Biarritz, France. He was recruited by the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios while a law student in Paris at the age of 25.

Bergerac met and married Ginger Rogers with whom he appeared in Twist of Fate(1954) (also known as Beautiful Stranger). He then appeared as Armand Duval in a television production of Camille for Kraft Television Theatre, opposite Signe Hasso. He played the Comte de Provence in Jean Delannoy‘s film, Marie Antoinette Queen of France.

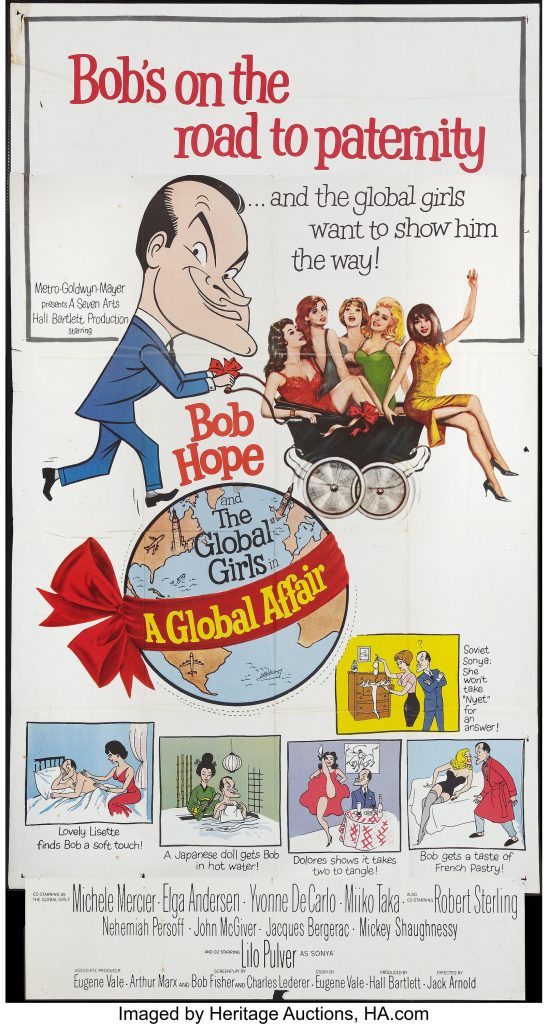

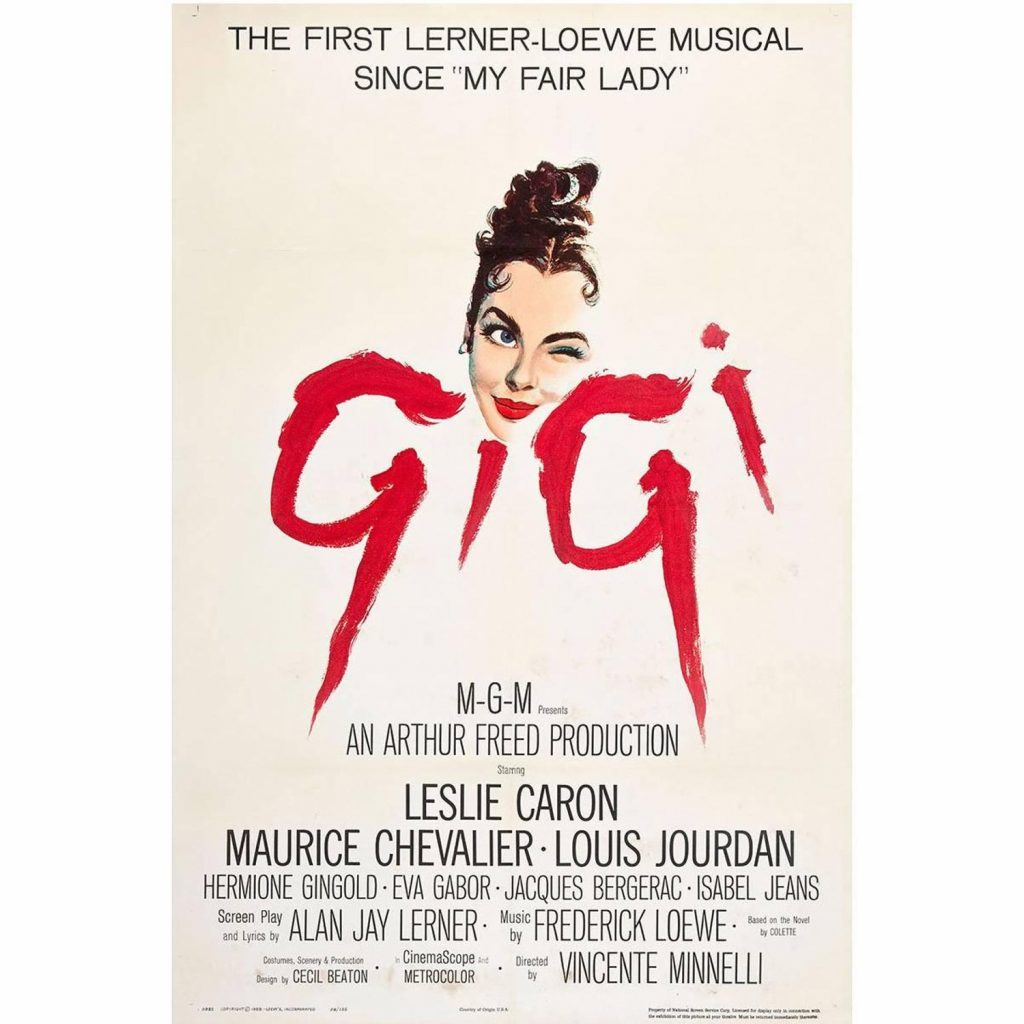

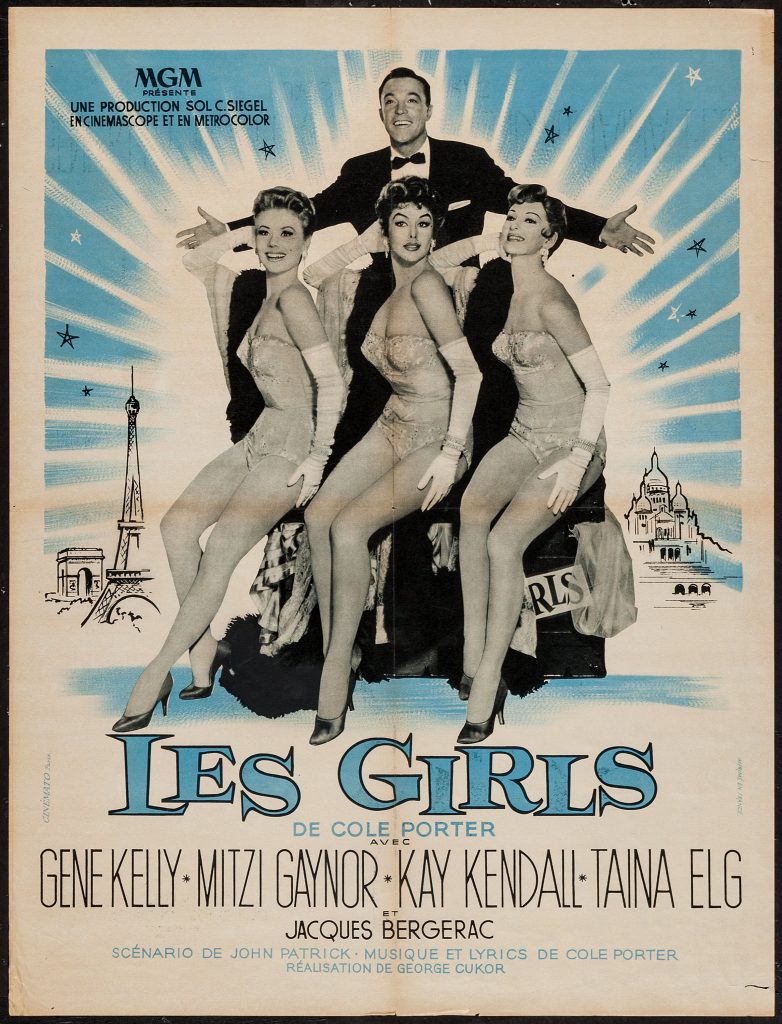

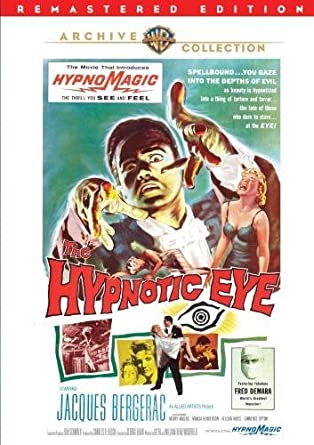

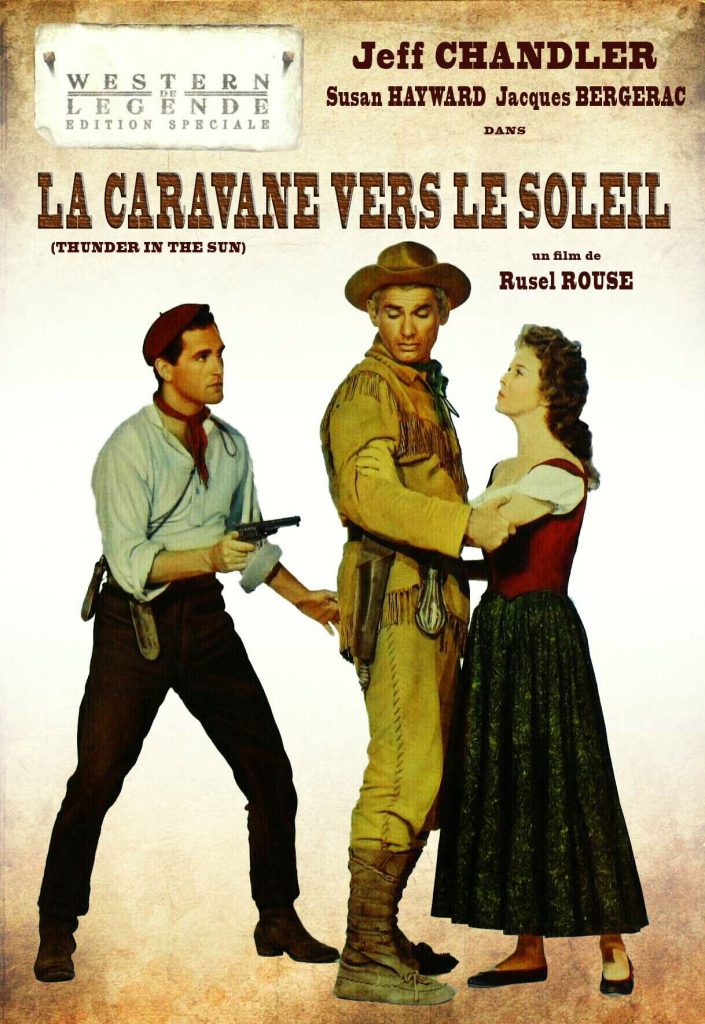

In Strange Intruder (1956), he shared the screen with Edmund Purdom and Ida Lupinoand in Les Girls (1957), he played the second male lead. He also appeared in Gigi(1958), Thunder in the Sun (1959), the cult horror film The Hypnotic Eye (1960) and A Global Affair (1964). In 1957, he received the Golden Globe Award for Foreign Newcomer.

He appeared in a few more films and on television including Batman, 77 Sunset Strip, Alfred Hitchcock Presents (3 episodes), The Lucy Show, Get Smart, The Dick Van Dyke Show and Perry Mason (Season 7, Episode 19).

His last appearance was on an episode of The Doris Day Show in 1969, after which he left show business and became the head of Revlon‘s Paris office and of the Perfumes Balmain company. His younger brother Michel became CEO of Revlon six years later.

He also managed the rugby club Biarritz Olympique from 1980 until 1981.

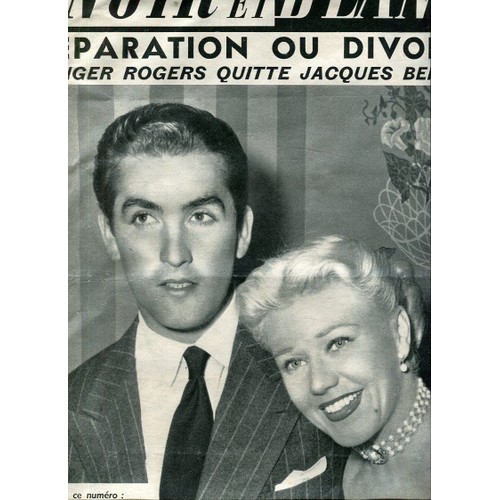

Bergerac married screen star Ginger Rogers in February 1953, and they divorced in July 1957. In June 1959, he married actress Dorothy Malone in Hong Kong, where she was on location for her 1960 film The Last Voyage. They had daughters Mimi and Diane together, and divorced in December 1964.

He died June 15, 2014, at his home in Anglet, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France.

- Liam

- No Comments

Marie-France Pisier obituary in “The Guardian” in 2011.

Marie-France Pisier

Marie-France Pisier was born in Vietnam in 1944 and died in 2011. At the age of twelve she came to live in Paris. Her breakthrough role came in 1968 in Francois Truffaut’s “Stolen Kisses”. In 1973 she had a critical and popular success with “Celine and Julie Go Boating”. “Cousin, Cousine” in 1975 was another very popular international success. She attempted a Hollywood career with “The Other Side of Midnight” and the television series “Scruples” amongst others . Her U.S. career was not particularly successful and she returned to work in France. She died in 2011.

Ronald Bergan’s “Guardian” obituary:

Those who followed the adventures of Antoine Doinel (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud) in a series of lyrical and semi-autobiographical films directed by François Truffaut – incorporating adolescence, marriage, fatherhood and divorce – will know that Doinel’s first and (perhaps) last love, Colette Tazzi, was played by the stunningly beautiful Marie-France Pisier, who has been found dead aged 66 in the swimming pool of her house near Toulon, in southern France.

Doinel and audiences first caught sight of Pisier in Antoine et Colette, Truffaut’s enchanting 32-minute contribution to the omnibus film L’Amour à Vingt Ans (Love at Twenty, 1962), during a concert at the Salle Pleyel in Paris of Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique. She is conscious of Antoine’s stares, and pulls down her skirt. We soon realise that Colette is going to break Antoine’s heart.

Léaud and Pisier were born in the same month and were both 18 when they appeared in the film. Pisier was discovered by a casting director, who had been instructed by Truffaut that: “Jean-Pierre Léaud’s partner must be a real young girl, not a Lolita, not a biker type, nor a little woman. She must be fresh and cheerful. Not too sexy.”

Colette, who treats Antoine like a “buddy”, much to his frustration, runs into him again briefly in Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses, 1968) and, finally, in the last film of the series, L’Amour en Fuite (Love On the Run, 1979), which she co-wrote. By then Colette was a lawyer, divorced like Antoine, but far more emotionally mature. The film contained what Truffaut called “real flashbacks”, when we see the differences between Pisier in her screen debut and Pisier 17 years and more than 20 films later, when she was midway through a prestigious career. She worked with such auteurs as Luis Buñuel, Jacques Rivette and Raúl Ruiz, appearing in quality French mainstream movies, with a short and unhappy detour to Hollywood.

Pisier was born in French Indochina, now Vietnam, where her father served as colonial governor. She moved to Paris with her family when she was 12. While starting out in films, she completed degrees in jurisprudence and political science at Paris University.

After she had appeared in several mediocre genre films, including thrillers directed by the actor Robert Hossein, Pisier’s career took a more interesting turn. In 1974, she appeared in the most outrageous and amusing sequence in Buñuel’s penultimate film, Le Fantôme de la Liberté (The Phantom of Liberty), where she is among the elegant guests seated on individual lavatories around a table from which they excuse themselves to go and eat in a little room behind a locked door. In the same year, in Céline et Julie Vont en Bateau (Céline and Julie Go Boating), Rivette’s brilliantly allusive comic meditation on the nature of fiction, she and Bulle Ogier act out, in a stylised and exquisite manner, a creaky melodrama in a mysterious housePisier was cast by the director André Téchiné in several of his early films, including Barocco (1976), for which she won a César award for her supporting role as a prostitute with a baby in tow. She later played Charlotte Brontë, alongside Isabelle Adjani (as Emily) and Isabelle Huppert (as Anne) in Téchiné’s Les Soeurs Brontë (1979).

Her performance as a frivolous, neurotic wife in Jean-Charles Tacchella’s Cousin Cousine (1975), a hit in the US, led to her starring role in The Other Side of Midnight (1977), a Hollywood soap opera in which she almost overcame the cliches as a naive French girl who, betrayed by an American pilot, begins to use men for their money and power.

But subsequently, apart from French Postcards (1979), in which, according to the critic Roger Ebert, “Marie-France Pisier, her jet-black hair framing her startling red lipstick, is the kind of dark Gallic woman-of-a-certain-age who knocks your socks off”, she was little seen in English-language movies. Among the rare exceptions was Chanel Solitaire (1981), in which she portrayed the designer Coco Chanel with her usual elegance. She made a splendid Madame Verdurin in Ruiz’s Proust adaptation, Le Temps Retrouvé (Time Regained, 1999), and was ethereal in the same director’s magical Combat d’Amour en Songe (2000).

More recently, she was an iconic presence in Christophe Honoré’s homage to the French new wave, Dans Paris (2006). Pisier also directed two films, Le Bal du Gouverneur (The Governor’s Party, 1990), starring Kristin Scott Thomas and adapted from Pisier’s own novel about some of her childhood spent in New Caledonia in the Pacific, and Comme un Avion (Like an Airplane, 2002), a family drama based on the death of her own parents.

Pisier was an outspoken defender of women’s rights and legal abortion. She overcame breast cancer in the 1990s. Her first husband was the lawyer Georges Kiejman, with whom she had a son. She is survived by her second husband, Thierry Funck-Brentano, a businessman; her brother, Gilles; and her sister, Evelyne.

• Marie-France Pisier, actor, writer, director, born 10 May 1944; died 24 April 2011

The above “Guaredian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

- Liam

- No Comments

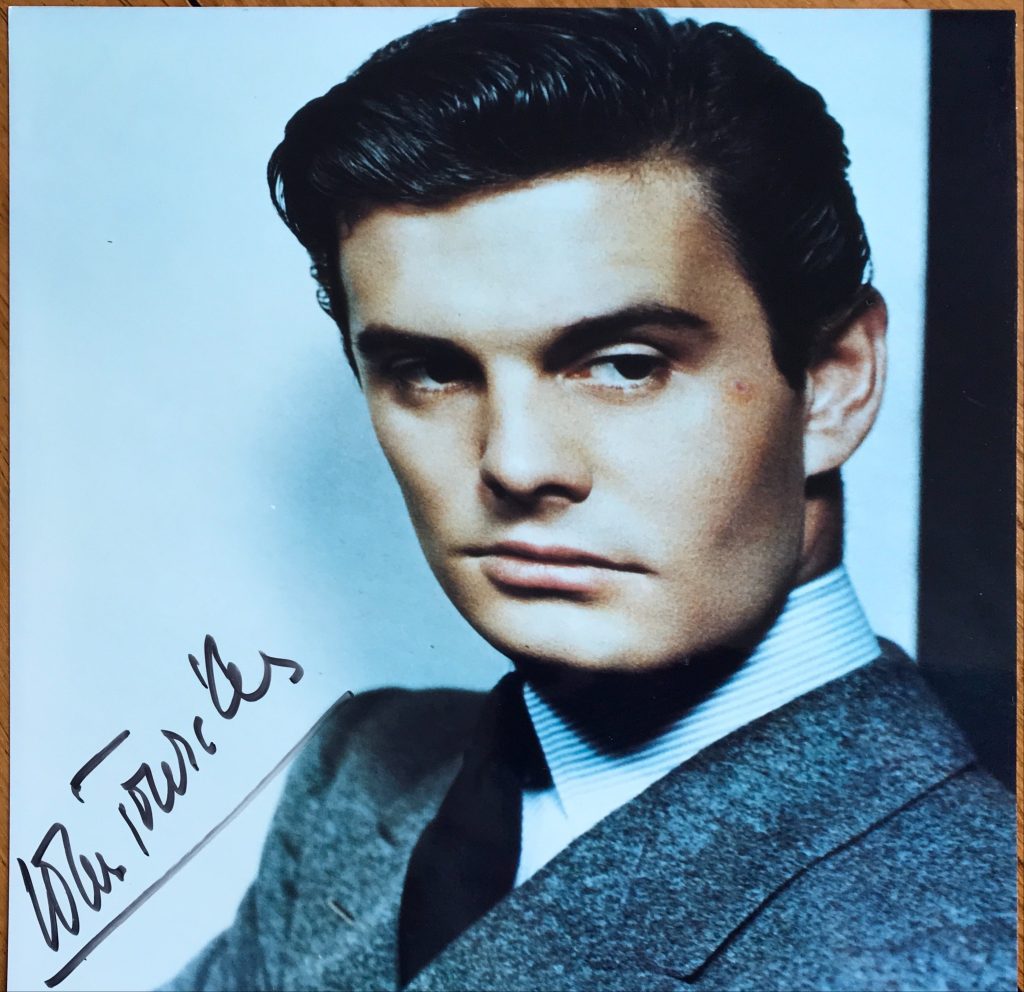

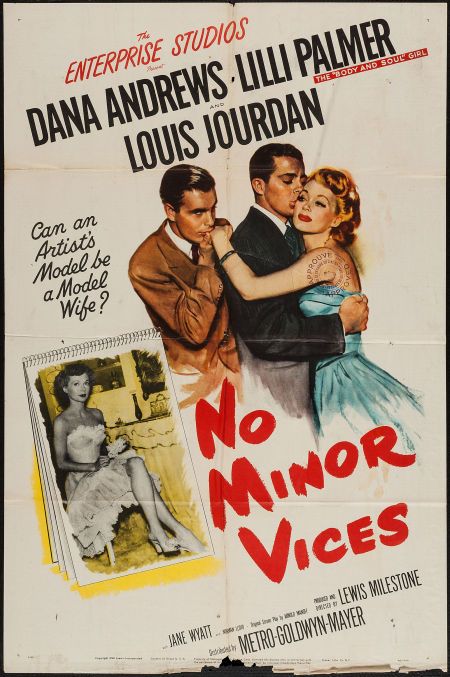

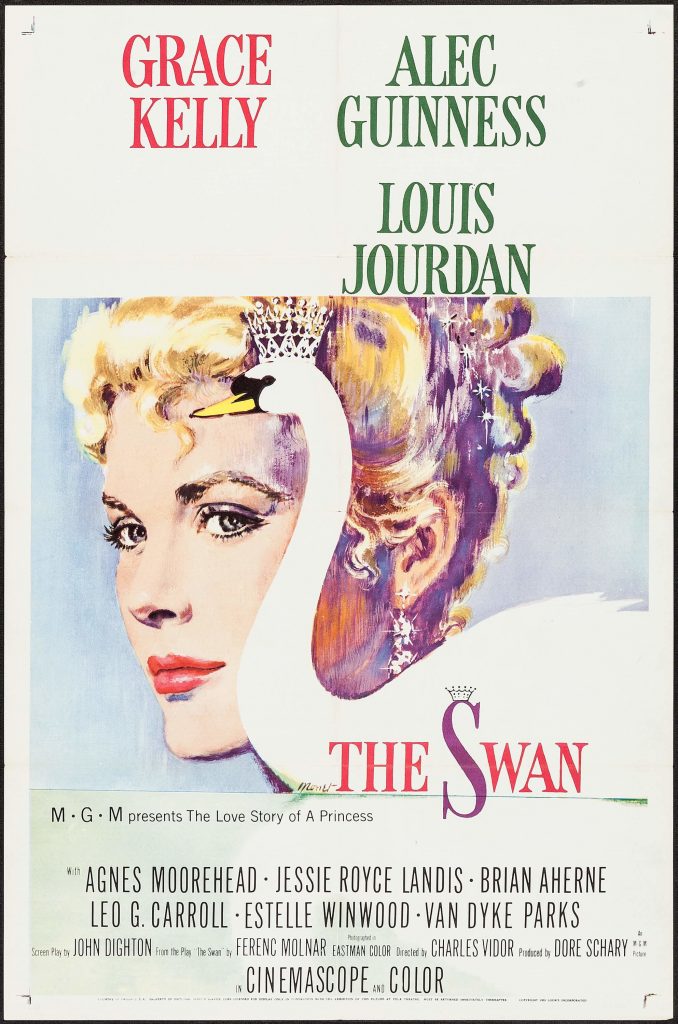

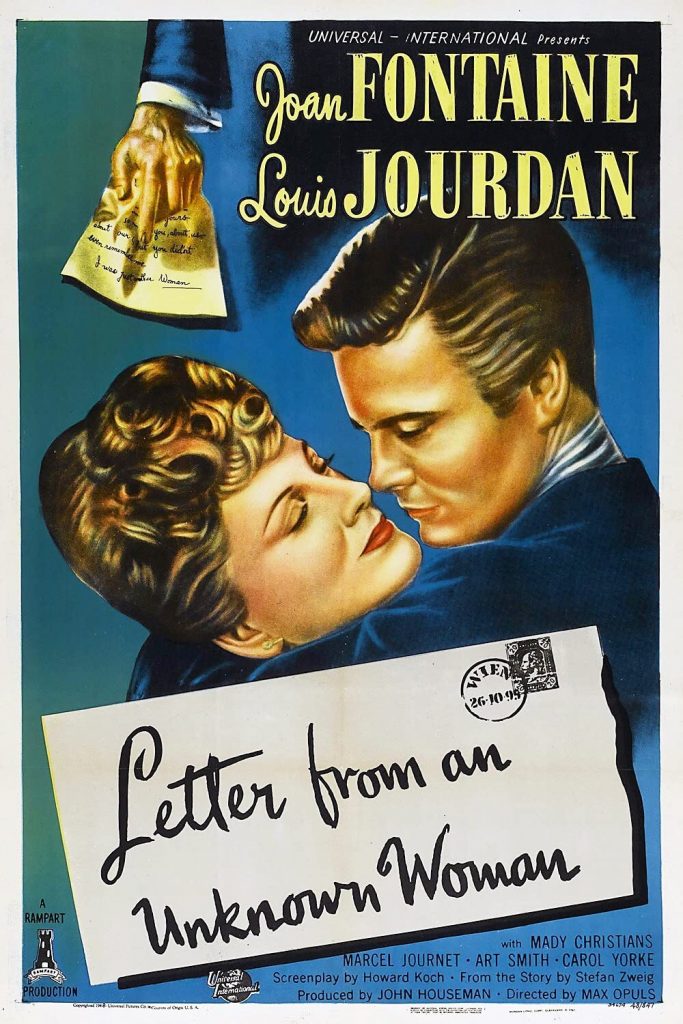

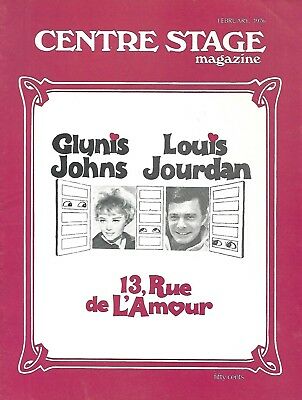

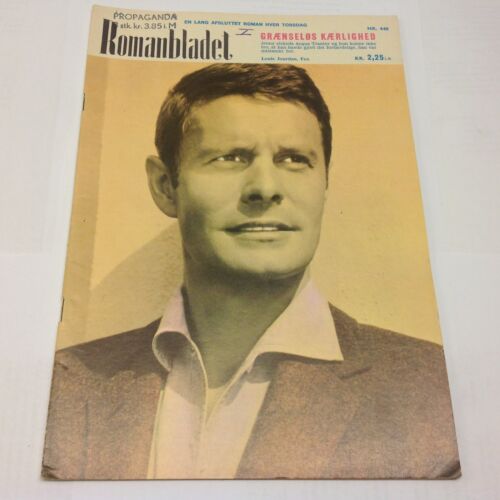

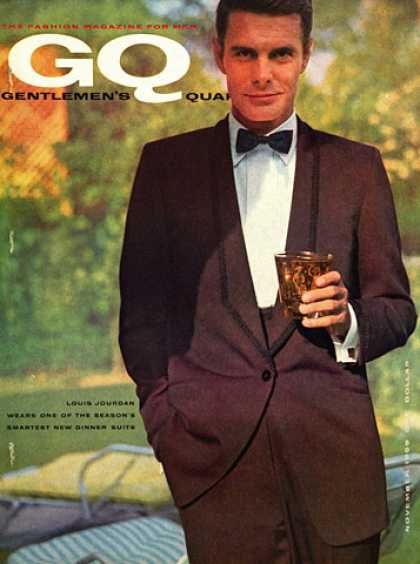

Louis Jourdan obituary in “The Independent”.

Good looks can be a mixed blessing for an actor. In the case of Louis Jourdan, the romantic star who died on Saint Valentine’s Day aged 93, they guaranteed him a career both in his native France and in Hollywood, but rarely in roles that moved him out of an audience’s comfort zone. A handsome devil to say the least, he was the absolute epitome of the suave, debonair, seductive Frenchman. The camera adored him, a creature of immaculate appearance and masculine finesse.

It was his role as the bon vivant enchanted by Leslie Caron’s flibbertigibbet debutante in Gigi (1958) that made him an international star. The film won nine Oscars and made Jourdan, who sang the title number, Hollywood’s favourite Frenchman. He was cast by producer Arthur Freed when Dirk Bogarde proved unavailable, Freed having delighted in Jourdan’s performance in Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) as the louche Prince Dino, a notorious womaniser whose girlfriends become known as “Venice girls” after he takes them to Venice for romantic trysts.

Born in Marseille in 1921 as Louis Robert Gendre, the son of hotelier Henry Gendre, he rubbed shoulders with the glitterati from an early age when his father ran a seaside hotel in Cannes and assisted in the running of an early incarnation of the city’s film festival. He was encouraged by the visiting stars, and although his father’s career moved the family to Turkey and England, the latter destination provided an excellent opportunity to master the English language. Back in France, he studied acting under René Simon at the École Dramatique, and upon graduating, took his mother’s maiden name of Jourdan.

He was spotted on stage in Paris by the screenwriter and director Marc Allégret, a prodigious talent-spotter who could also claim to have discovered Gérard Philipe, Roger Vadim and Michèle Morgan. Allégret gave him work as an assistant camera operator on a drama within a drama school, Entrée des Artistes (The Curtain Rises), in 1938, as preparation for his movie debut the following year in another story of actors finding the line between work and play blurring, Le Corsaire (The Pirate). Adapted from a play by Marcel Achard, the film offered Jourdan the chance to act opposite Charles Boyer, a French star in Hollywood who Jourdan would go on to emulate. It was a hotly anticipated project, but shooting was halted after a month as France mobilised for war, and the film was never completed.

He did get to act opposite another major star, albeit a fading one, Ramon Novarro, in his eventual film debut, La Comédie du Bonheur (The Comedy of Happiness) in 1940, before war put his career on hold.

During the war, his father was a prisoner of the Gestapo, while Jourdan and his brother were active members of the Resistance, printing and distributing leaflets. He refused to appear in films propagandising Philippe Pétain’s collaborationist government, a stand which made him rightly cherished when the French film industry rebuilt itself in the post-war years.

He left for Hollywood in 1946 at the invitation of David O Selznick, and made a good first impression as a man of mystery in the courtroom drama The Paradine Case (1947), a costly affair directed by Hitchcock and starring Gregory Peck. No aspiring movie star could have wished for better company to ride into town with, although the film turned out to be a disappointment. His much better second Hollywood film got him his name above the title and allowed him to add depth to another smouldering lothario: Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), co-starring Joan Fontaine, is an affecting study of unrequited love that remains a powerful watch today. It was the work of another European in Hollywood, director Max Ophüls, which perhaps explains the skillful dodging of tuppeny novelette melodrama for delicate emotional exploration.

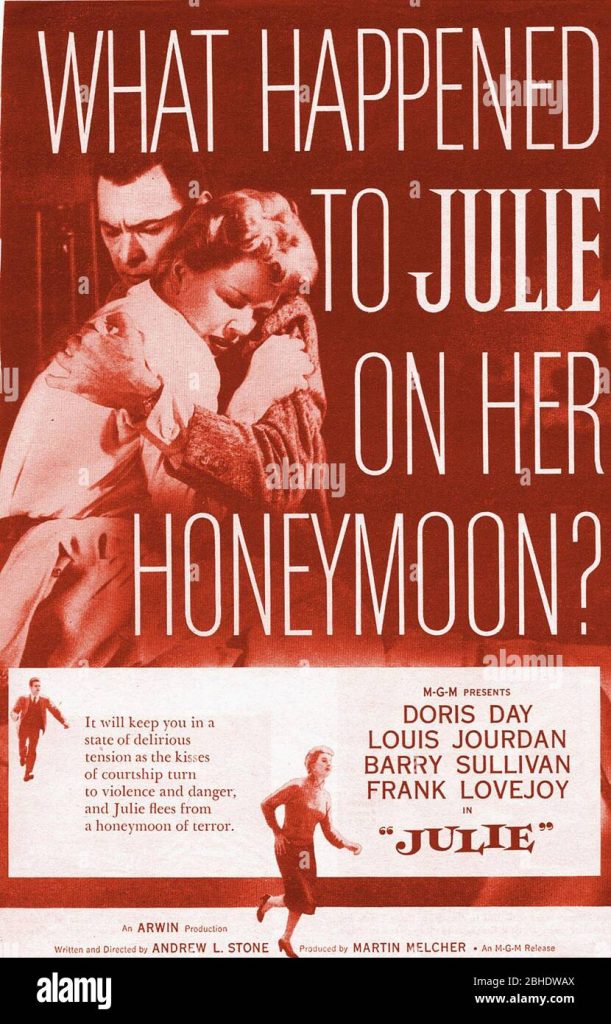

Louis Jourdan in ‘Gigi’ (Getty)He began to sense the perils of typecasting when appearing as the lover of adulterous Jennifer Jones in Vincente Minnelli’s Madame Bovary (1949), and in an attempt to break free of such roles, returned to France briefly, where he continued to play lovers, but of a slightly different style: the philandering was strictly for fun in Rue de l’Estrapade (1953) for instance, and his features lent themselves well to villainous roles when he played Doris Day’s psychotic husband in Julie (1956). However, he was by his own admission, “a star without a hit” until he surrendered to Three Coins in the Fountain (1954) and then Gigi (1958), which overwhelmed his attempts to break free of light romantic leads.

His Gigi co-star, Leslie Caron, remembered that he was “one of the handsomest men in Hollywood, but not comfortable with his image”, a predicament he shared with the aforementioned Dirk Bogarde. He regularly claimed he was “Hollywood’s French cliché”, in parts that involved “mostly cooing in a woman’s ear”, Gigi in particular making him world famous as “a colourless leading man”.

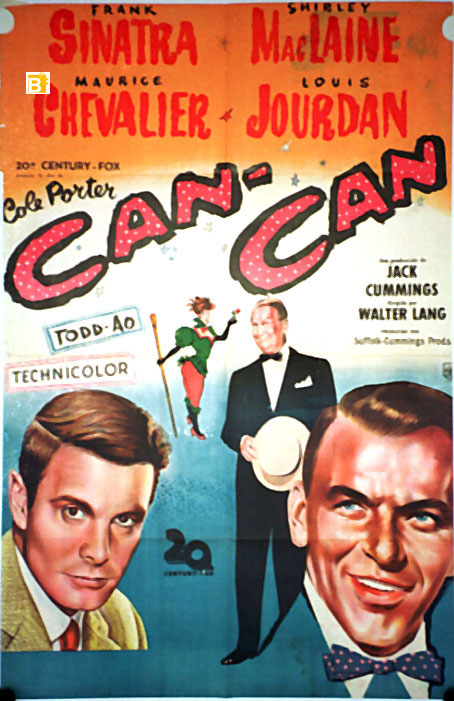

He remained a bankable star in Hollywood following the success of Gigi: he followed it up with another musical, Can-Can (1960), co-starring Frank Sinatra and Shirley Maclaine, but his most interesting work was generally to be found elsewhere. His Broadway debut, in the lead role for the Billy Rose stage adaptation of André Gide’s novel The Immoralist, at the Royale Theatre in 1954, was a bold undertaking: he not only played a gay man, but worked in between a brittle James Dean and his then lover, the intense Geraldine Page. The performance won him a Donaldson Award for Best Actor.

He made his American television debut starring in the detective series Paris Precinct for ABC in 1955, but it was a medium he fared better with in Britain, where he was occasionally cast much more imaginatively – on one occasion as the persecuting husband in Gaslight, opposite Margaret Leighton, for ITV in 1960, and for Lew Grade in 1975, playing De Villefort to Richard Chamberlain’s Count of Monte Cristo.

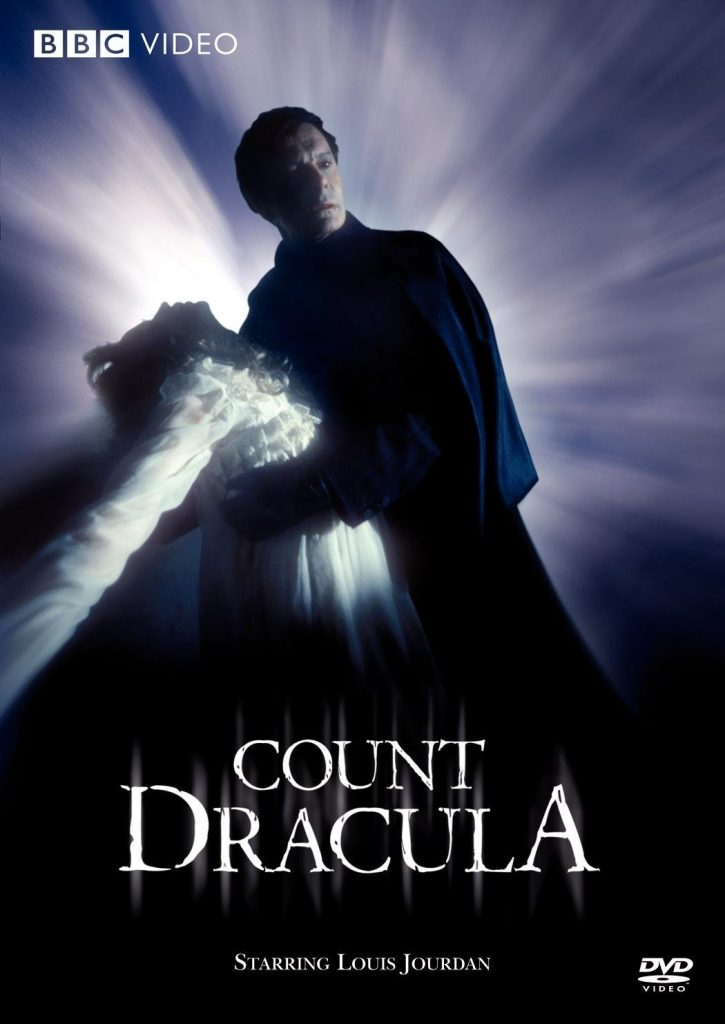

One of the most interesting moments in his career came when Philip Saville cast him as the lead in Count Dracula (1977), a weighty BBC dramatisation that remains one of the most faithful imaginings of the source material, coming just after Hammer Films had given up the ghost. Jourdan’s casting surprised the critics, but, speaking to the Radio Times in 1977, Saville explained that he saw Dracula as “a romantic, sexually dashing anti-hero in the tradition of those figures usually dreamed up by women… Rochester, Heathcliff… figures that can overpower a strong heroine, inhuman figures that can’t be civilised.” Ahead of the game in finding romanticism in vampirism, the drama occasionally lacks bite – but Jourdan remains one of the most interesting and original Draculas in screen history.

He was the best thing in Octopussy (1983), an otherwise lousy Bond film which even lacked a memorable theme song, and bowed out with a similarly suave villain in Peter Yates’s Year of the Comet in 1992, the year he retired. Sadly, few of the roles in his final years are much to speak of.

Although his career was plentiful, it was hamstrung by poor timing and monotonous casting. Nevertheless, he was always a pleasure to watch, a naturally appealing performer. Despite his lothario image, he remained married to his childhood sweetheart, Berthe (known by the nickname Quique) for 67 years, until her death last year. They had one son, who fell victim to drug addiction and died in 1981.

Whenever he spoke in interviews of his enduring marriage, his seductive but sincere voice and passionate conviction could, in Ophelia’s words, move the stoniest breast alive, and reminded one that he was a star of the kind that they just don’t make anymore.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

- Liam

- No Comments

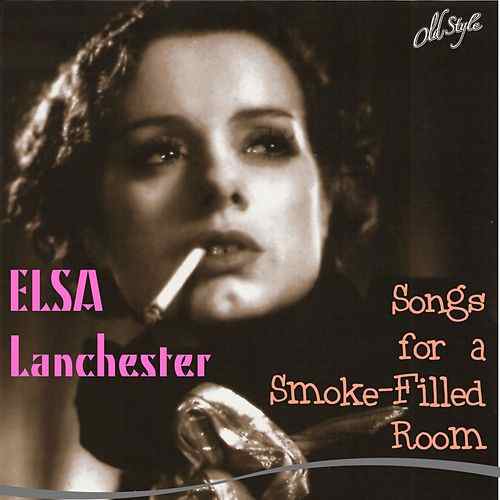

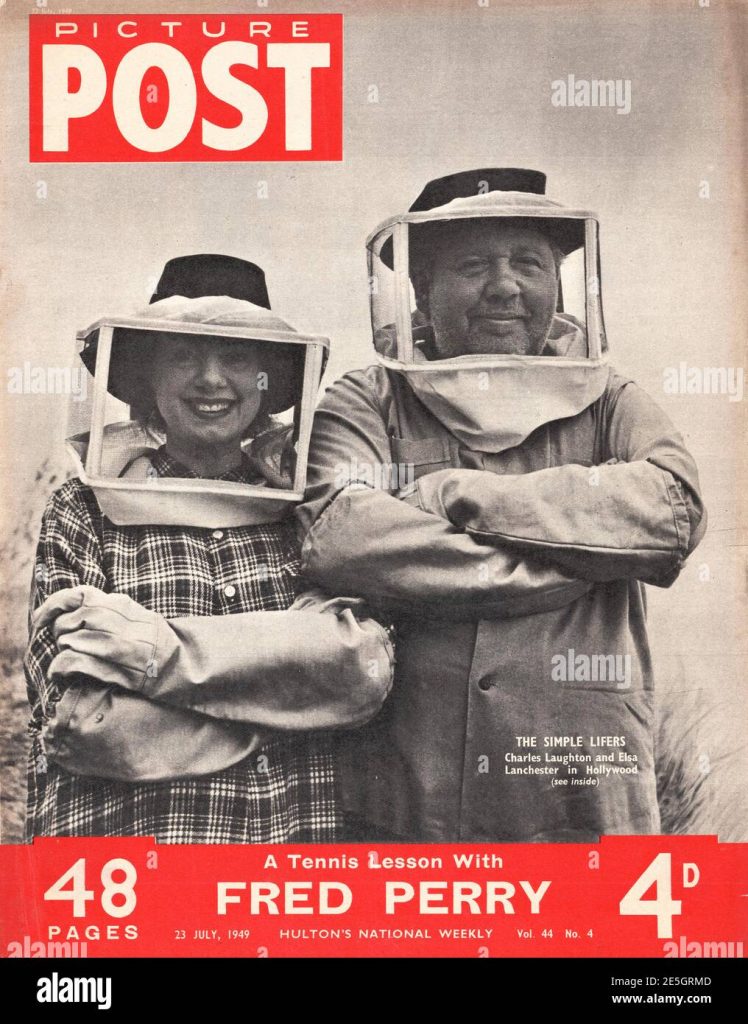

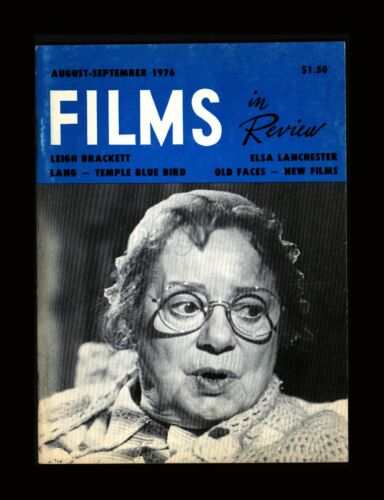

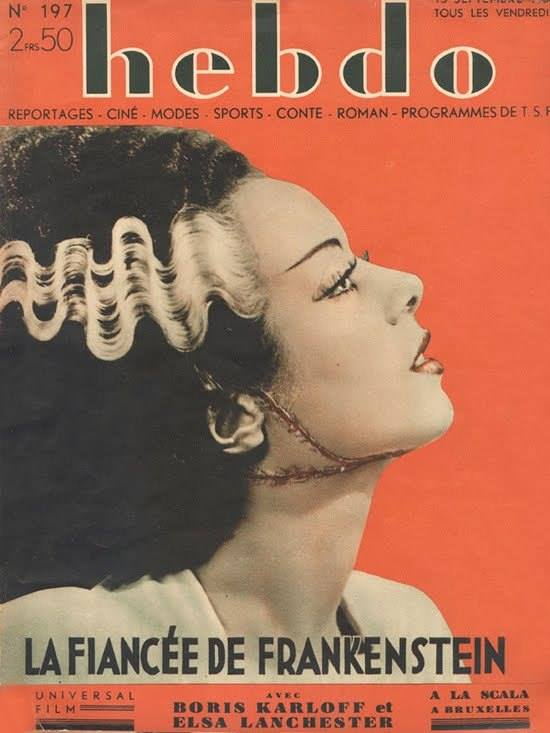

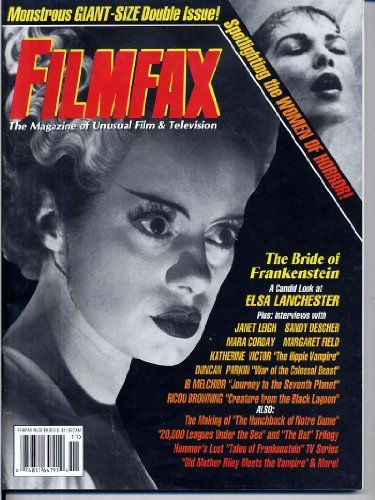

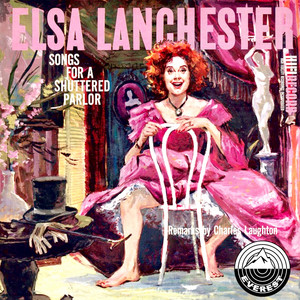

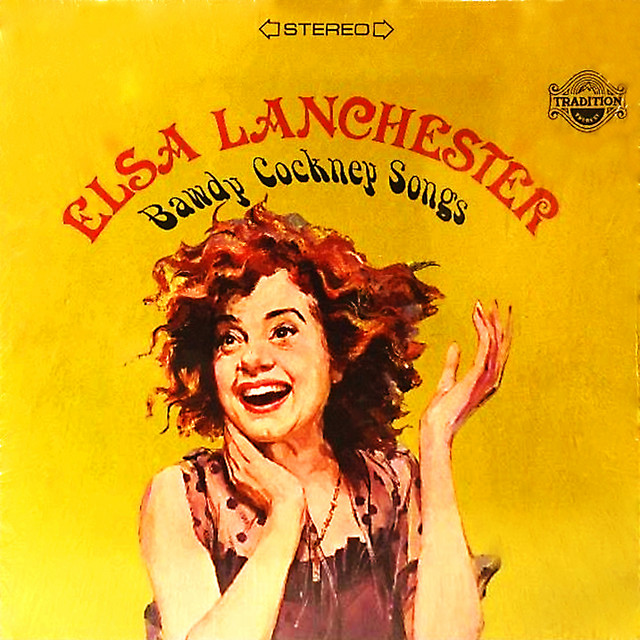

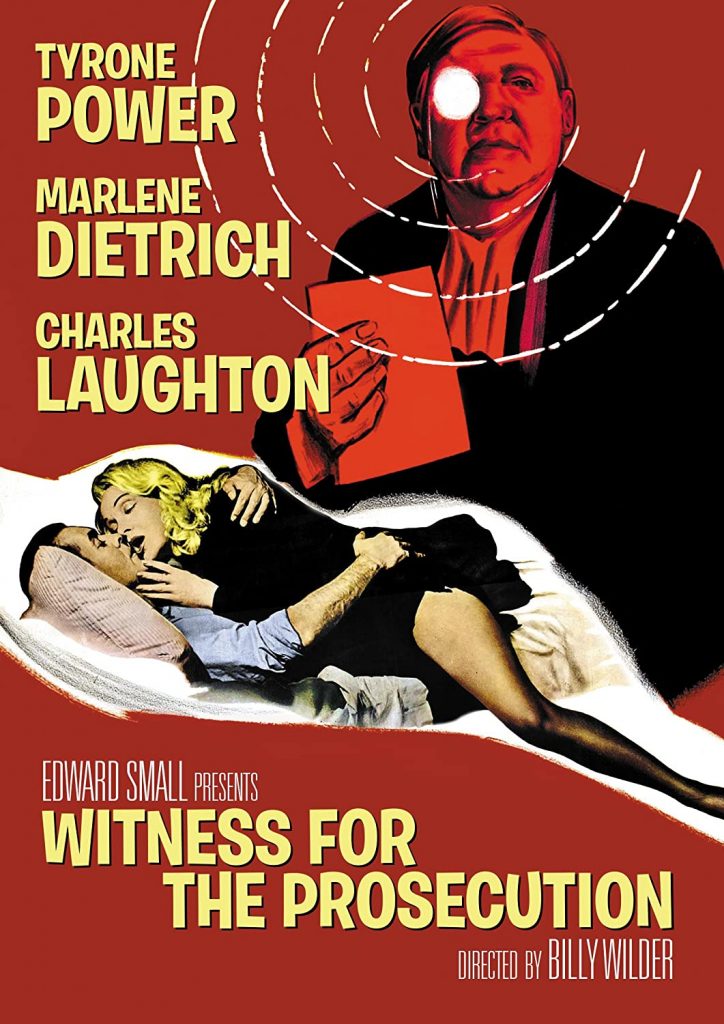

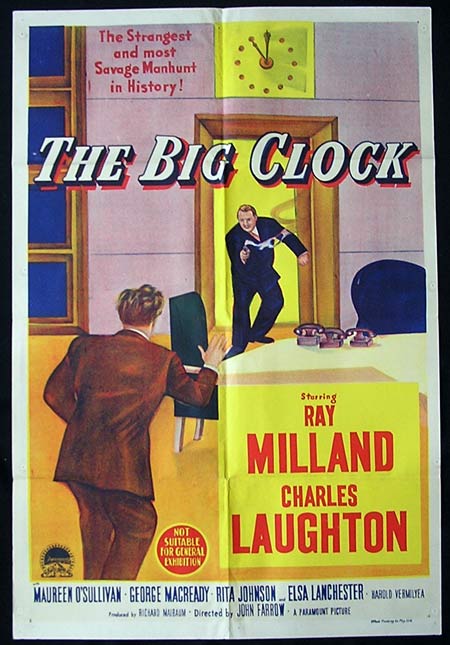

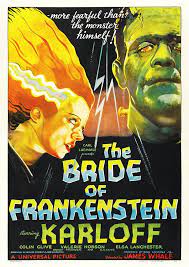

Elsa Lanchester

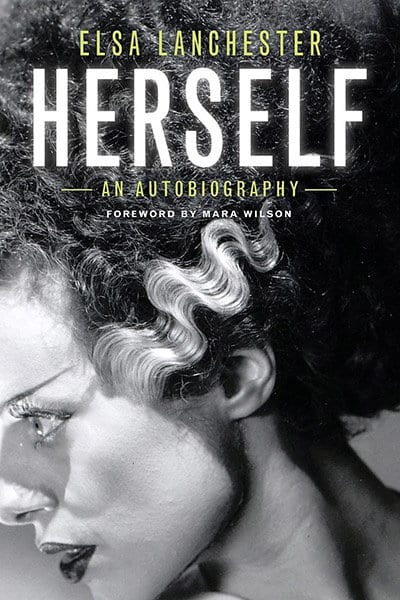

Elsa Lanchester was the character actress par excellance. When one saw her name in the credits of a movie, you eagerly anticipated her appearance becasue she enlivened all the films she appeared in. Her droll delivery was always a delight. She was born in 1902 in London. As a child she had been a dance with the troupe managed by Isadora Duncan. She married Charles Laughton in 1929. She had appeared in revue in London but went with Laughton to Hollywood in the early 1930’s. Her career was subordinated to his, which was a great pity becasue I think she was the much more talented of the two. In 1935 she made her most famous film “THe Bride of Frankenstein”. She was exceptional in “David Copperfield”, “Lassie Come Home”, “The Razor’s Edge”, “Come to the Stable”, “The Big Clock”, “Mystery Street” and “Witness for the Prosecution”. Her autobiography which was published a few years before her death in 1986. Rare footage of interview with Elsa Lanchester on the Dick Cavett Show can be viewed here.

Article on Elsa Lanchester on “Tina Aumont’s Eyes” website:

With her large eyes and upturned nose, Elsa Lanchester was not your conventional film beauty, but with her vast talent and distinctive qualities, she went on to have a fantastic career spanning 55 years, even if she was often typecast as the lovable spinster or dotty old woman.

Born Elizabeth Lanchester Sullivan in London, on October 28th 1902, Elsa held early dreams of becoming a dancer, and by 1922 was busy performing on stage. In 1924 she opened a nightclub in London, but closed it in 1928 as her film career was starting to take off. The following year Elsa married actor Charles Laughton and, although theirs was an open marriage, they would stay together until Laughton’s death in 1962.

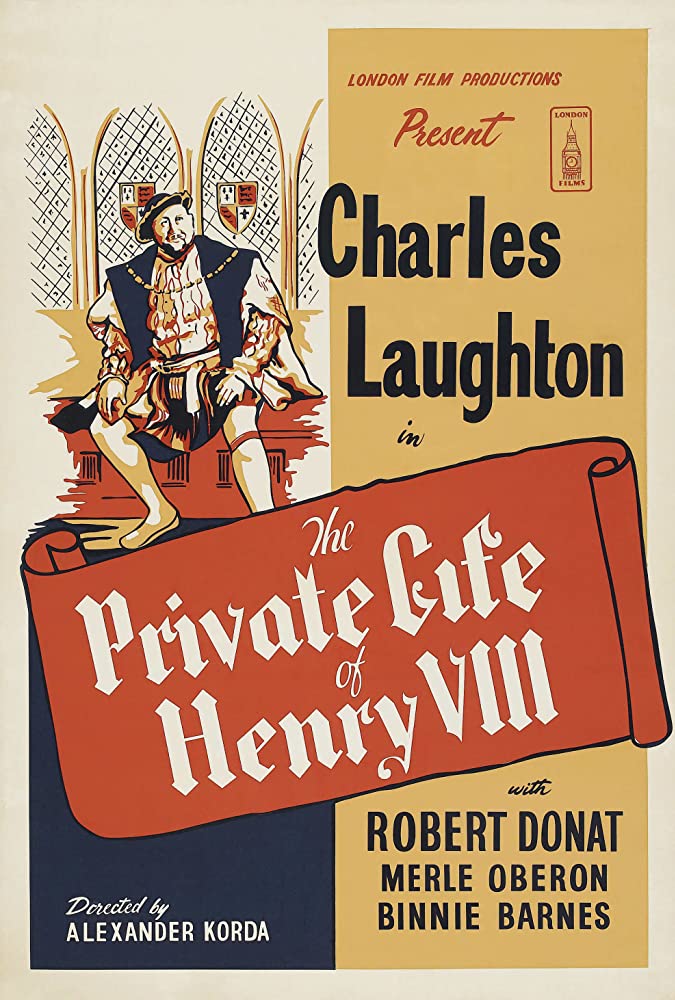

Lanchester’s first role of note came in 1933 when, alongside Laughton, she played Anne of Cleves in ‘The Private Life of Henry VIII’, which deservedly won Laughton the Best Actor Oscar. 1935 was the breakthrough year for Lanchester when she played W.C. Fields’ maid in George Cukor’s ‘David Copperfield’, and then earned screen immortality with her portrayal of the Bride, in James Whale’s masterpiece ‘The Bride of Frankenstein’ (’35). I have always found her wild-haired creature strangely attractive, as she sashays across the screen with her arms out-stretched and making her hissing sounds. Even though it’s a brief role at the end of the picture, it remains Lanchester’s most iconic part. Another memorable performance at this time was when she played Hendrickje the maid, in Alexander Korda’s excellent biopic ‘Rembrandt’ (’36), which boasted a superb turn by Laughton in the title role.

Relocating to America in 1940, Lanchester was given some excellent supporting roles including that of Roddy McDowall’s impoverished mother in the hugely popular family drama ‘Lassie Come Home’ (’43), which brought 11 year old Elizabeth Taylor to the fore. Following minor parts in a couple of superb movies; ‘The Razor’s Edge’ and ‘The Spiral Staircase’ (both ’46), Elsa was charming as Matilda the maid, in the Cary Grant romantic comedy ‘The Bishop’s Wife’ (’47). After supporting Laughton and Ray Milland in the 1948 noir ‘The Big Clock’, Elsa received her first Oscar nomination for her fine portrayal of a religious painter in Henry Koster’s French nun drama ‘Come to the Stable’ (’49), starring Loretta Young and Celeste Holm.

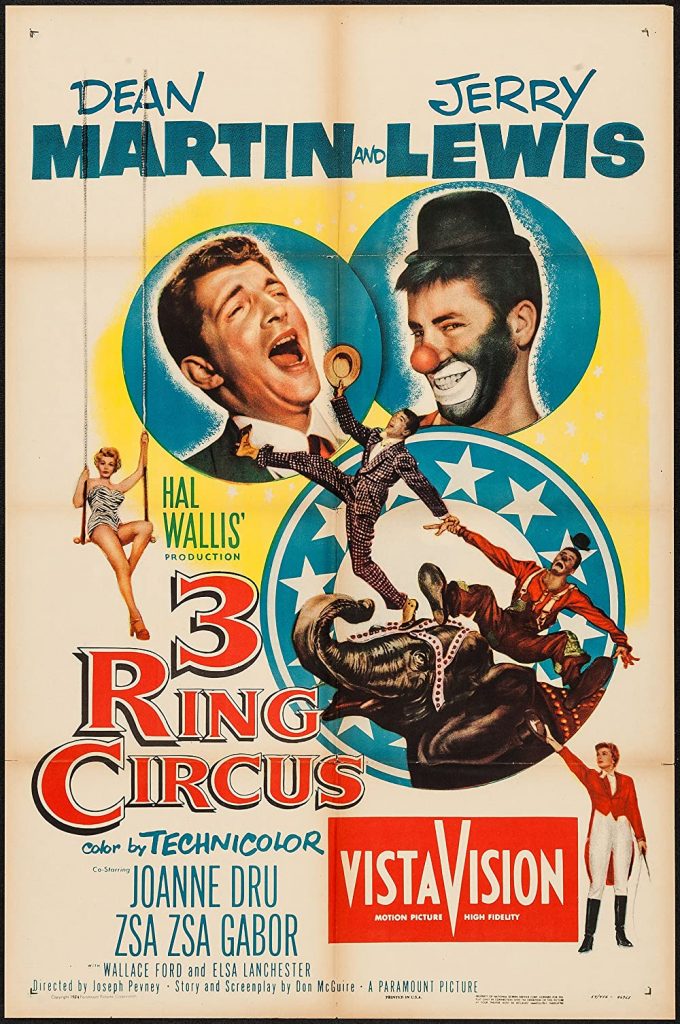

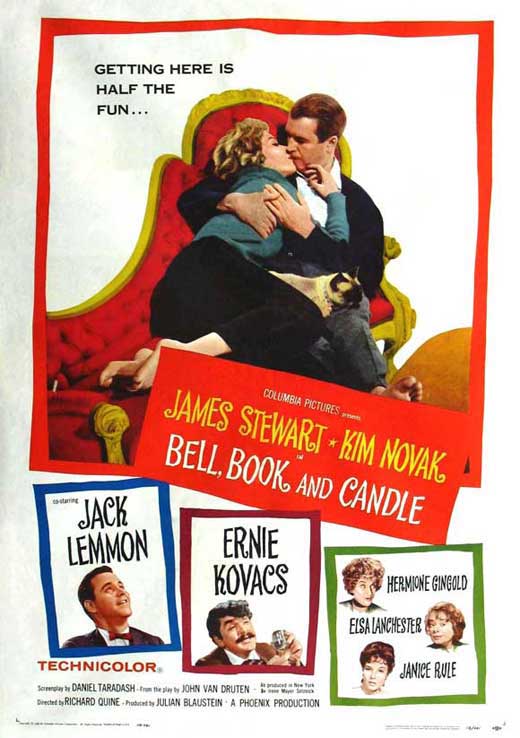

After playing a countess in the 1950 Joel McCrea western ‘Frenchie’, and lusting after Clifton Webb’s former matinee idol in the excellent comedy ‘Dreamboat’ (’52), Elsa was the bearded lady in the minor Dean Martin-Jerry Lewis vehicle ‘3 Ring Circus’ (’54). A fun part followed as Leslie Caron’s witty stepmother in the delightful musical ‘The Glass Slipper’ (’55), MGM’s colourful take on Cinderella. I loved Elsa’s stuffy yet kindly nurse; Miss Plimsoll, in Billy Wilder’s superb courtroom thriller ‘Witness for the Prosecution’ (’57), sparring endlessly with Charles Laughton’s recovering barrister. Elsa would receive her second Oscar nomination for her wonderful performance. Another fun role followed with the Richard Quine sleeper ‘Bell, Book and Candle’ (’58), as witch Kim Novak’s dotty aunt.

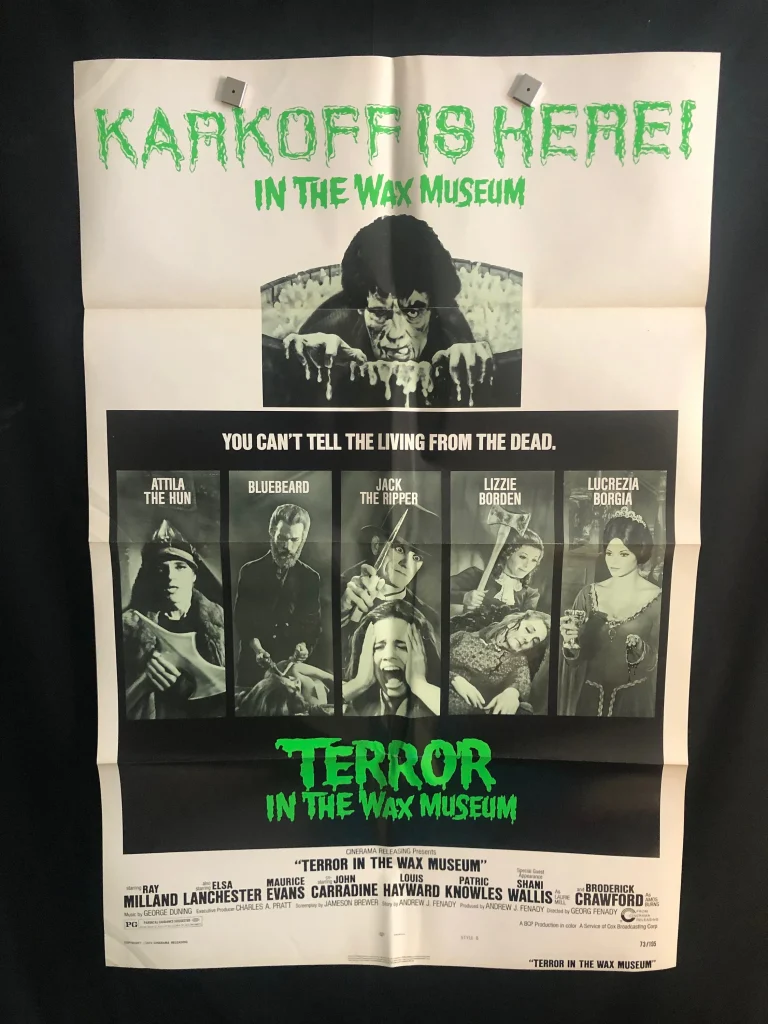

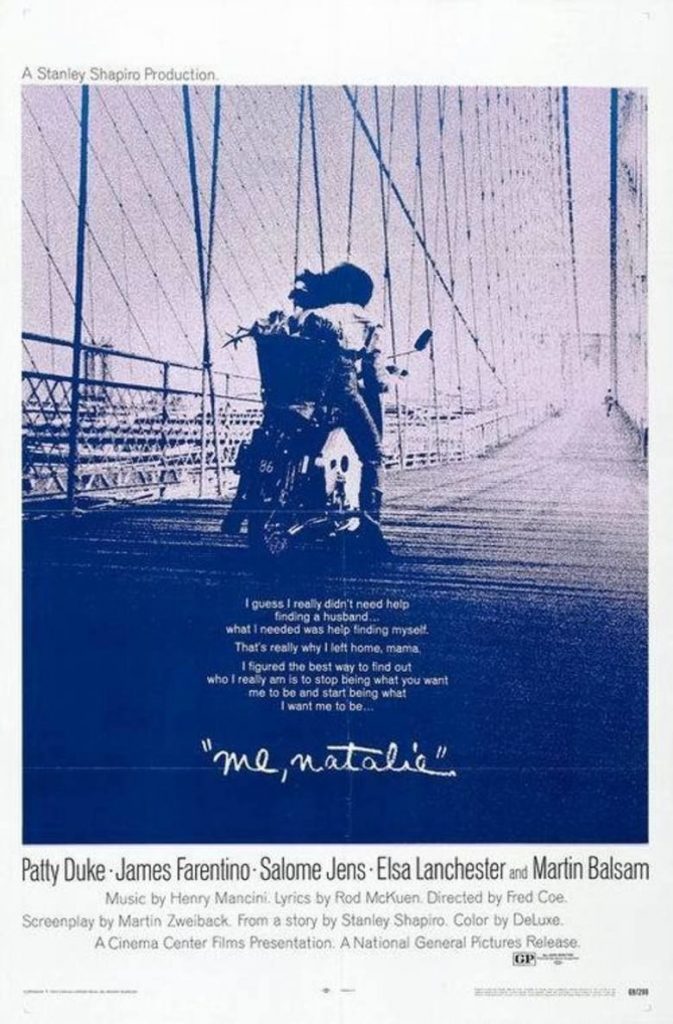

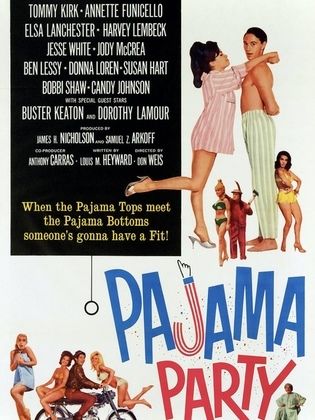

A handful of Disney appearances came next, first with a small role as a disgruntled nanny in ‘Mary Poppins’ (’64), ‘That Darn cat!’ (’65), as a prying neighbour, and (my childhood favourite) ‘Blackbeard’s Ghost’ (’68), as an elderly descendant of Peter Ustinov’s mischievous spirit. Another eccentric role followed with the enjoyable Patty Duke vehicle ‘Me, Natalie’ (’69), as Patty’s oddball landlady, and then Daniel Mann’s interesting cult horror ‘Willard’ (’71), in which she played the ailing mother to Bruce Davison’s social outcast. Another horror, albeit a bad one, followed with ‘Terror at the Wax Museum’ (’73), slumming it alongside aging stars Ray Milland and Broderick Crawford. I loved her funny turn as Jessica Marbles, in Neil Simon’s hilarious star-filled spoof ‘Murder by Death’ (’76), playing a lovable sleuth wheeling around her childhood nurse; 93 year old Estelle Winwood. Elsa’s final movie was the pleasant Robby Benson comedy ‘Die Laughing’ (’80), before her retirement to the Hollywood hills.

On Boxing Day 1986, Elsa Lanchester died from pneumonia in her Californian home. She was 84 years old. A supremely talented actress, Elsa brought humour, mischief and warmth to a wealth of movies and television appearances. From small scene-stealing roles to large-scale melodramas, it was always a joy to see her smiling face up there on the screen. A true and unique one-off!

Favourite Movie: The Razor’s Edge

Favourite Performance: Witness for the Prosecution

The above article can also be accessed online here.

- Liam

- No Comments

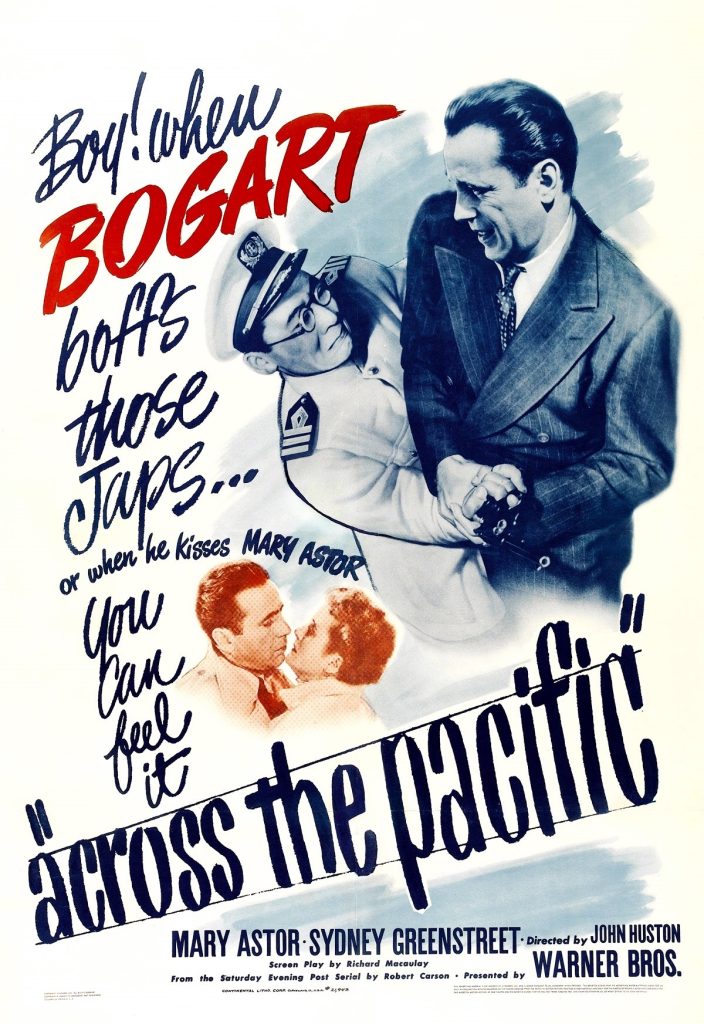

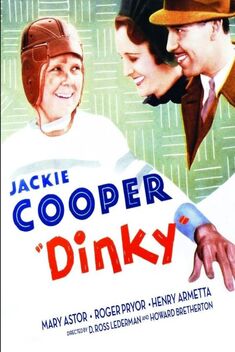

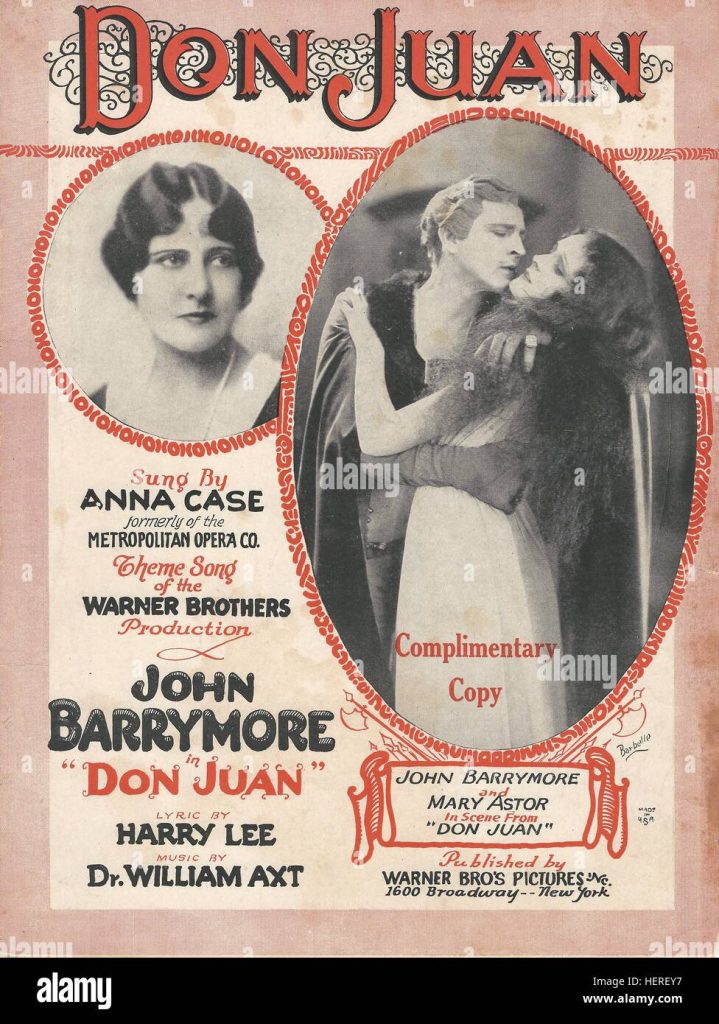

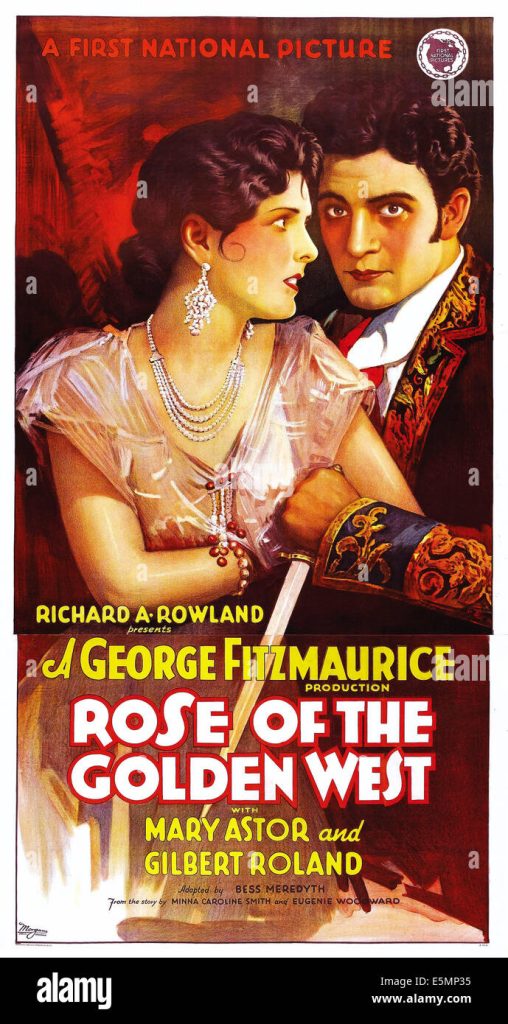

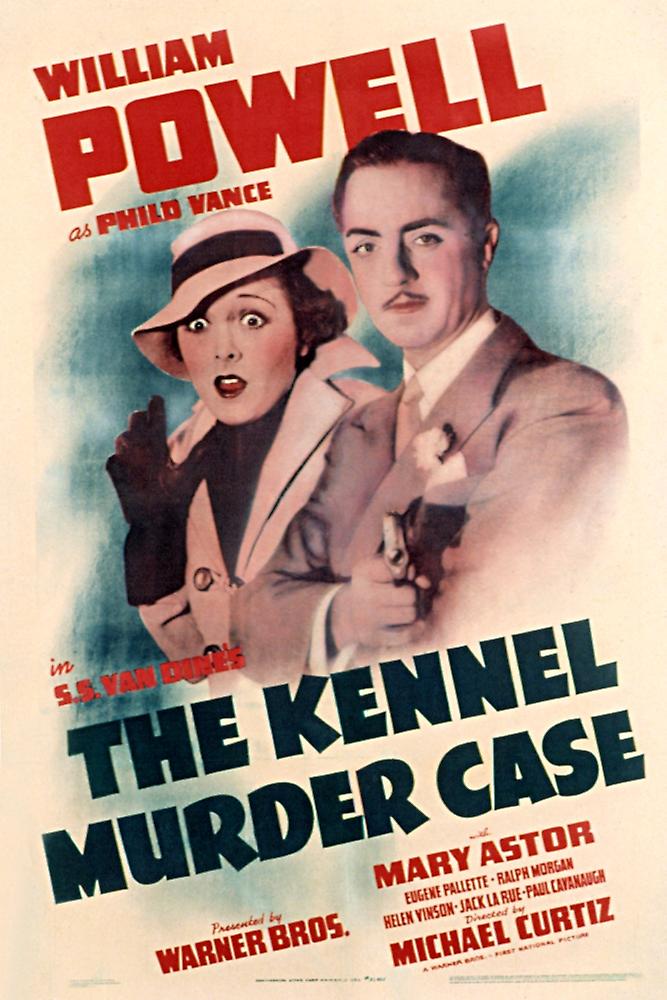

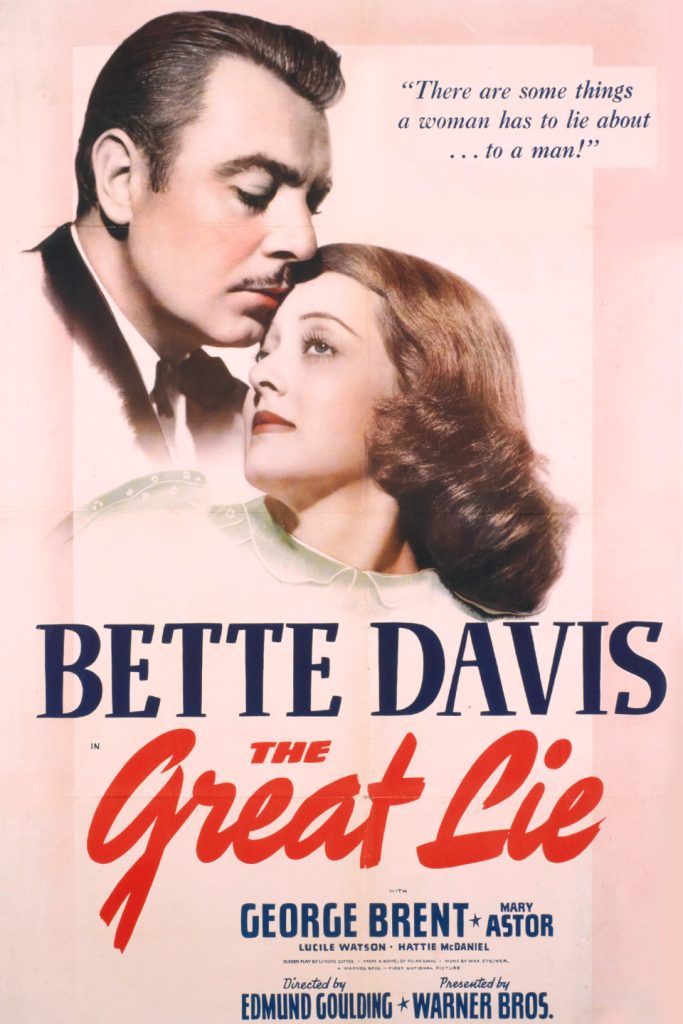

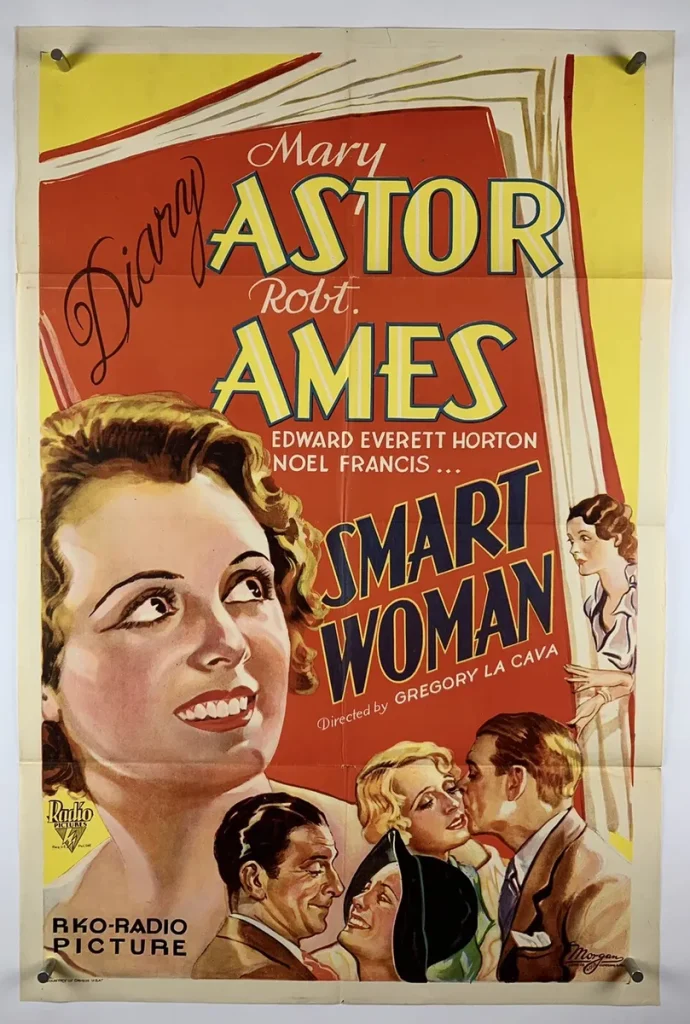

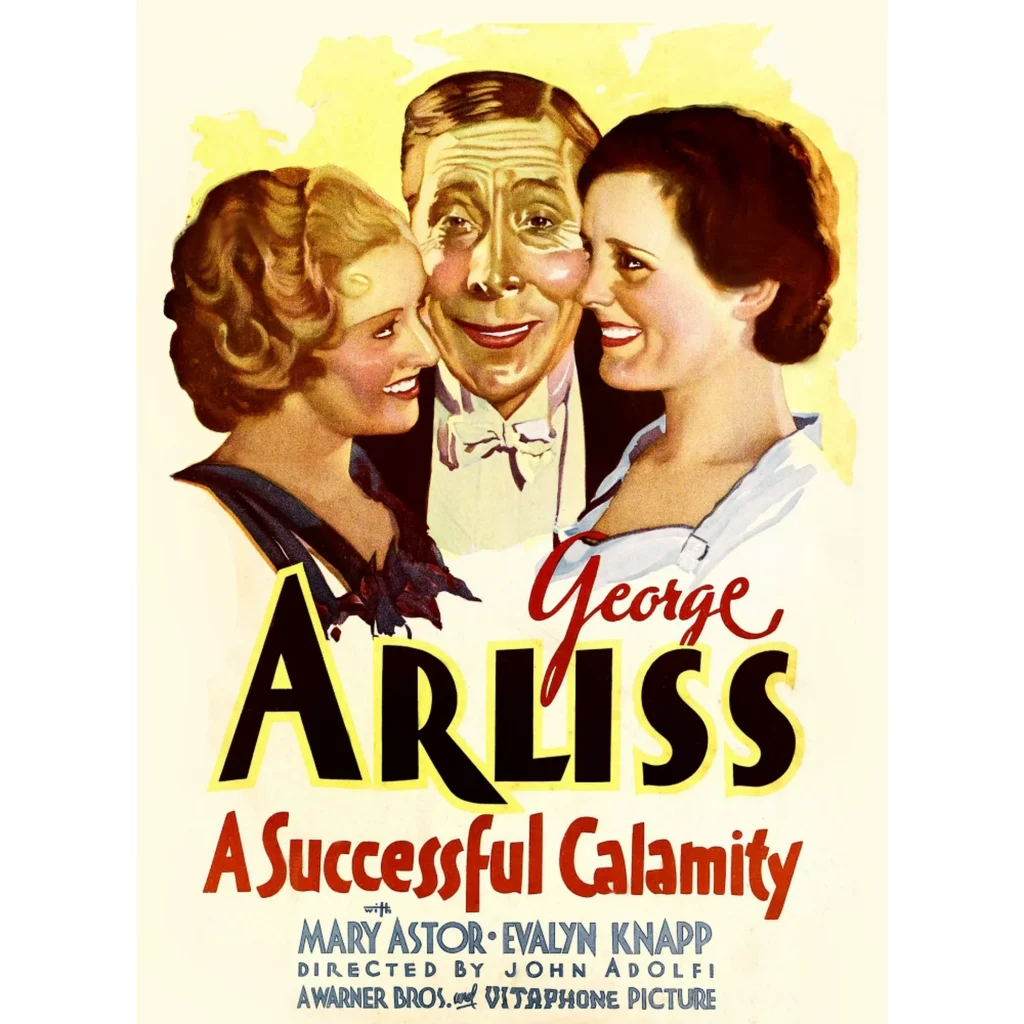

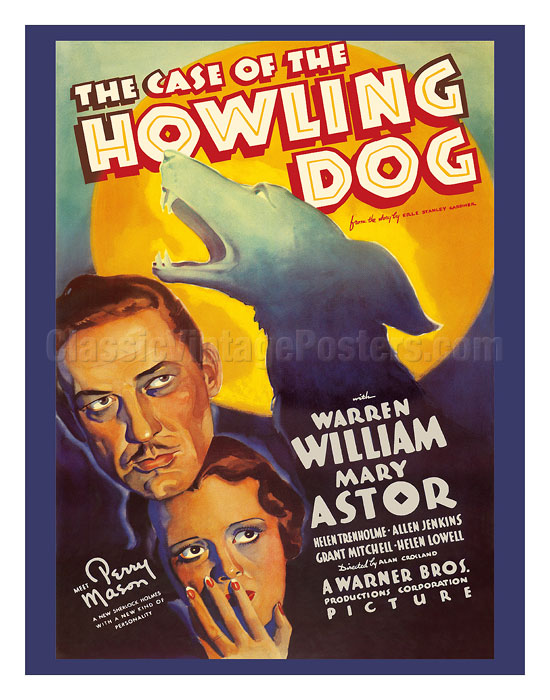

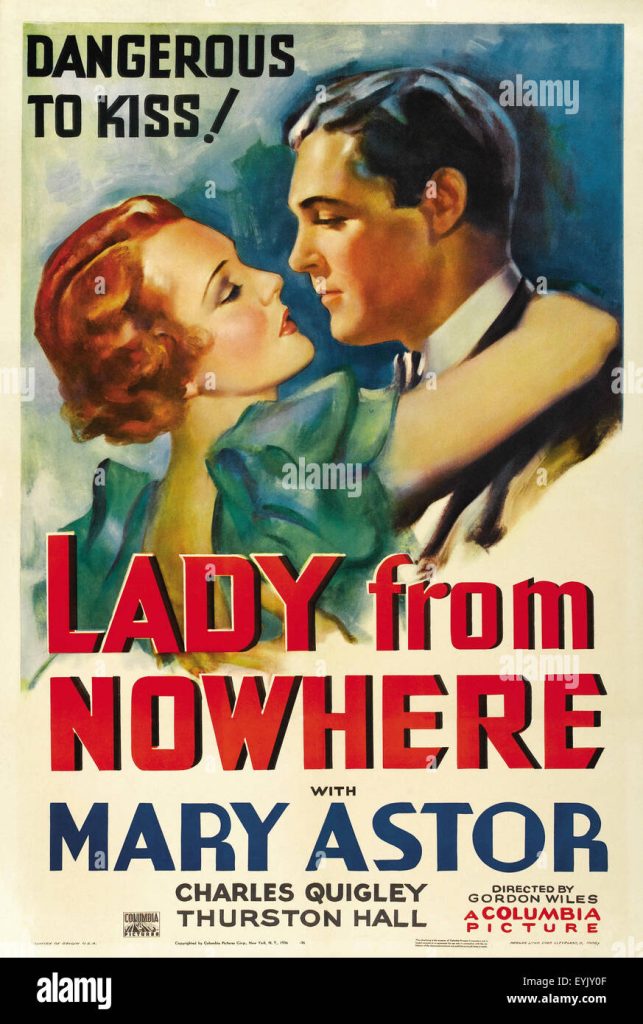

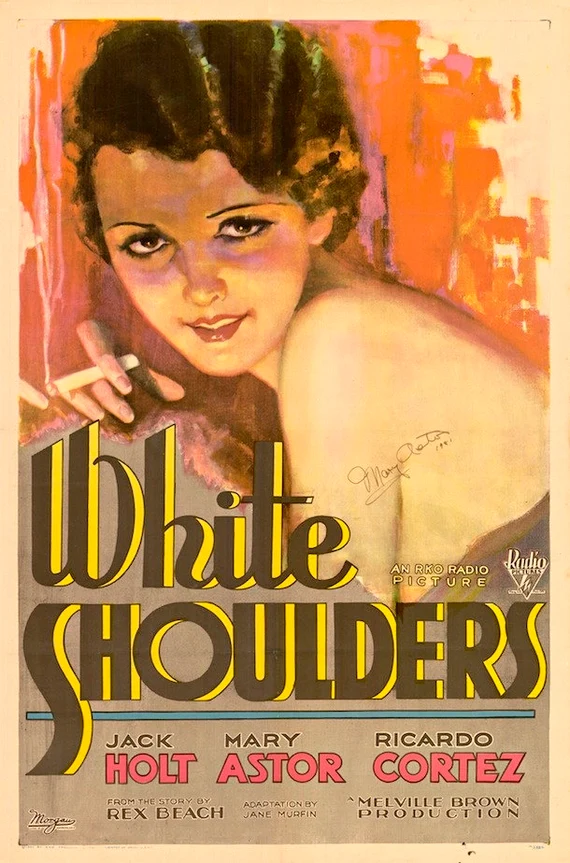

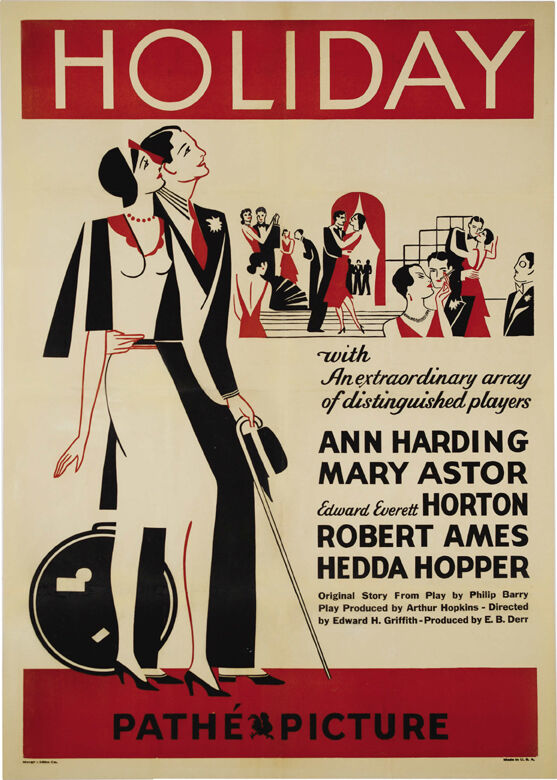

“The wide range of Mary Astor took her, with total conviction, from bitchy vixens to sensible mothers, sweethearts to dangerous femme fatales. Although one often thinks of her as appearing in other star’s movies, she is very much one of the outstanding players of Hollywood’s prime decades. ” – “The Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors” by Barry Monush.

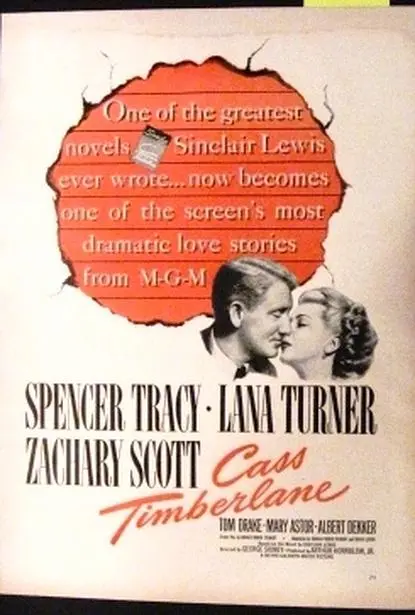

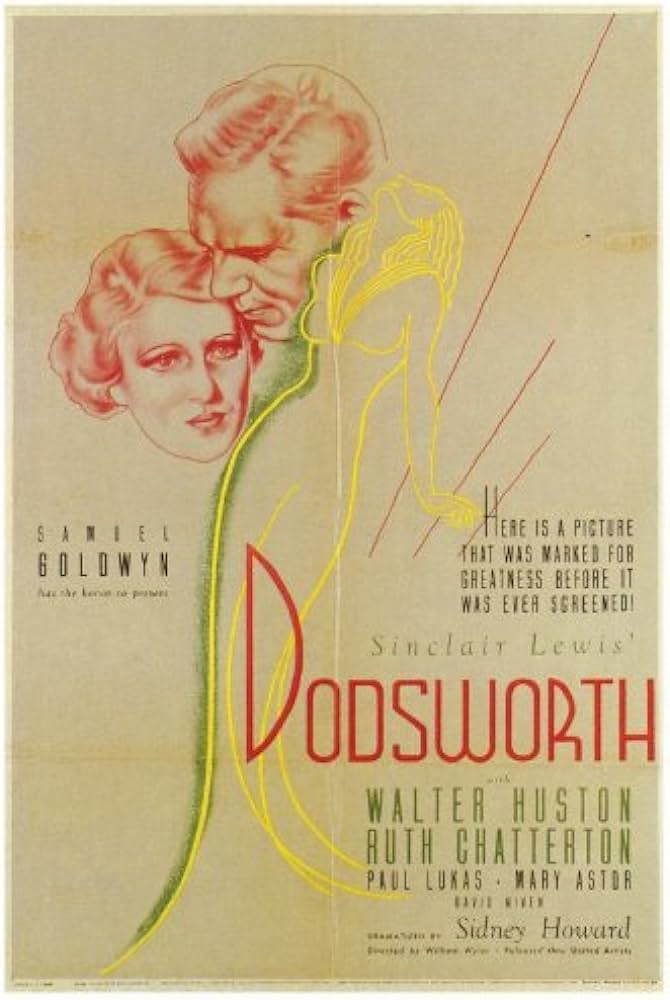

“Among buffs at least, Mary Astor’s reputation today stands second to none. During a very long career she made many films that have been much-revived, and her acting, incisive but delicate, is not the least factor in their reappearance. Inevitably, in over 100 films, she played the same part countless times, with a neat line in bitches at one end and syrupy moms at the other. The only consistent in her portrayals were her beauty and a brittleness, she was never less than competent and frequently more. She chose to be a featured player, which meant that her parts were often small and non-sustaining. She had to make the maximum effect in a few minutes. It is know that she cared little for her craft, but much thought and sensitivity went into her best interpretations. Given a big – and sometimes difficult- role, as in “Dodsworth” and “The Maltese Falcon”, she achieved greatness” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars” (1970).

Mary Astor had a very long career stretching back to silent film. She was born in 1906 in Quincy, Illnois. She made her film debut in 1920 in the silent film “The Scarecrow”. In 1926, John Barrymore cast her opposite him in “Don Juan”. Her beautiful speaking voice ensured a smooth transition to sound movies. Throughout the 1930’s she gave several fine performances. In “Dodsworth” she was particularly effective opposite Walter Huston. In 1941 she played Brigid O’ Shaughnessy in “The Maltese Falcon” opposite Humphrey Bogart. The following year she won the Academy Award for “The Great Lie” with Bette Davis. In the late 40’s she made a series of mother roles including “Little Women” with Margaret O’Brien, Elizabeth Taylor, June Allyson and Janet Leigh. Her last film was “Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte” with Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland in 1964. Mary Astor became a well-respected author. She died in 1987.

An overview of her career on TCM, please click here.

- Liam

- No Comments

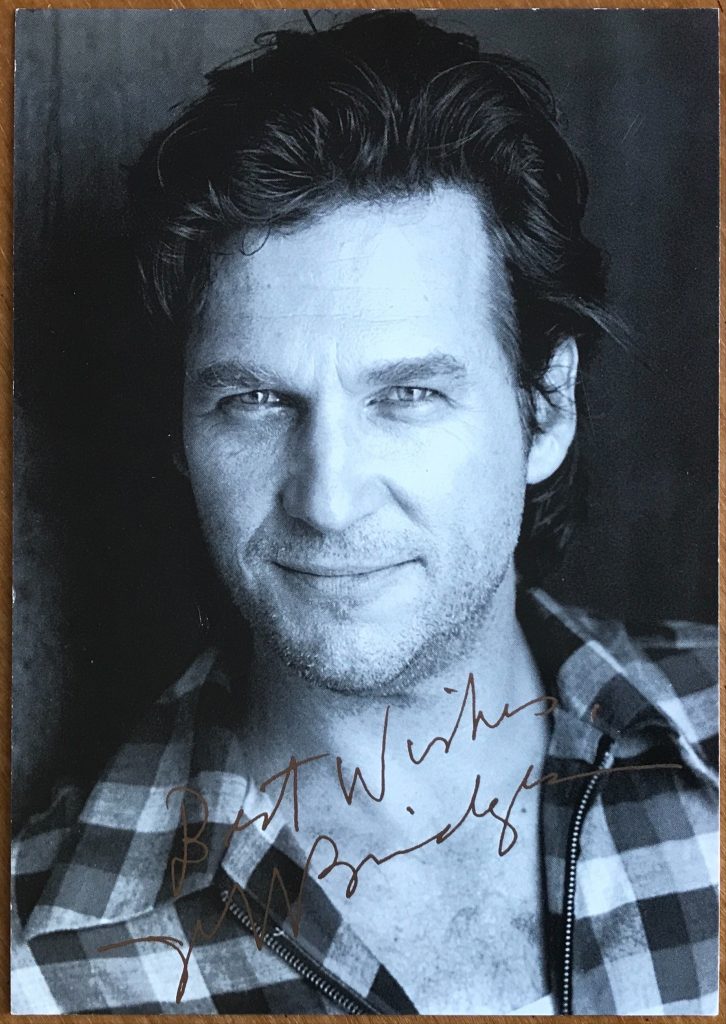

“Jeff Bridges was in movies for over a decade before stardom came, and that was partly because he chose the wrong parts – or else they did not allow him to do what he does best, to embody the average guy who is slow in though and quick in action. Now the word ‘average’ is a giveaway – you would never have called Wayne or Cooper or Tracy ‘average’ – though like them Bridges has a distinctive voice – low and thin which never see,s to strive for the unexpected cadences on which it alights. This is hardly the heroic age in movies: no Bengal Lancers, no cavalry leaders – but it was clear a while back that Bridges has developed that charisma the big screen likes so much. He has also become a very good actor, adept with a witty line and always relaxed, natural but withall vulnerable. Observing once that he was probably not bankable. He said ‘I’ve got mixed feelings about it. I’d like to get a crack at the great scripts but I think of myself as more of a character actor. I’m afraid to get typecast in one role. Look what happened to my dad'”

. – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The Independent Years” (1991).

Jeff Bridges has just won an Oscar for his performance in “Crazy Heart”. He has served a long apprenticeship. His first feature film was “Halls of Anger” in 1970. He has many film performances to his credit including “The Last Picture Show”, “Fat City”, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot” and “Jagged Edge”. He was born in 1949 in Los Angeles. His father was the actor Lloyd Bridges. It is very gratifying to see him finally get his due recognition. Jeff Bridge’s website can be accessed here.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

The son of well-known film and TV star Lloyd Bridges and his long-time wife Dorothy Dean Bridges, Jeffrey Leon Bridges was born on December 4, 1949 in Los Angeles, California, and grew up amid the happening Hollywood scene with big brother Beau Bridges. Both boys popped up, without billing, alongside their mother in the film The Company She Keeps (1951), and appeared on occasion with their famous dad on his popular underwater TV series Sea Hunt (1958) while growing up. At age 14, Jeff toured with his father in a stage production of “Anniversary Waltz”. The “troublesome teen” years proved just that for Jeff and his parents were compelled at one point to intervene when problems with drugs and marijuana got out of hand.

He recovered and began shaping his nascent young adult career appearing on TV as a younger version of his father in the acclaimed TV-movie Silent Night, Lonely Night(1969), and in the strange Burgess Meredith film The Yin and the Yang of Mr. Go (1970). Following fine notices for his portrayal of a white student caught up in the racially-themed Halls of Anger (1970), his career-maker arrived just a year later when he earned a coming-of-age role in the critically-acclaimed ensemble film The Last Picture Show(1971). The Peter Bogdanovich– directed film made stars out off its young leads (Bridges,Timothy Bottoms, Cybill Shepherd) and Oscar winners out of its older cast (Ben Johnson,Cloris Leachman). The part of Duane Jackson, for which Jeff received his first Oscar-nomination (for “best supporting actor”), set the tone for the types of roles Jeff would acquaint himself with his fans — rambling, reckless, rascally and usually unpredictable).

Owning a casual carefree handsomeness and armed with a perpetual grin and sly charm, he started immediately on an intriguing 70s sojourn into offbeat filming. Chief among them were his boxer on his way up opposite a declining Stacy Keach in Fat City (1972); his Civil War-era conman in the western Bad Company (1972); his redneck stock car racer in The Last American Hero (1973); his young student anarchist opposite a stellar veteran cast in Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh (1973); his bank-robbing (also Oscar-nominated) sidekick to Clint Eastwood in Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974); his aimless cattle rustler in Rancho Deluxe (1975); his low-level western writer who wants to be a real-life cowboy in Hearts of the West (1975); and his brother of an assassinated President who pursues leads to the crime in Winter Kills (1979). All are simply marvelous characters that should have propelled him to the very top rungs of stardom…but strangely didn’t.

Perhaps it was his trademark ease and naturalistic approach that made him somewhat under appreciated at that time when Hollywood was run by a Dustin Hoffman, Robert De Niro and Al Pacino-like intensity. Neverthless, Jeff continued to be a scene-stealing favorite into the next decade, notably as the video game programmer in the 1982 science-fiction cult classic TRON (1982), and the struggling musician brother vying with brother Beau Bridges over the attentions of sexy singer Michelle Pfeiffer in The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989). Jeff became a third-time Oscar nominee with his highly intriguing (and strangely sexy) portrayal of a blank-faced alien in Starman (1984), and earned even higher regard as the ever-optimistic inventor Preston Tucker in Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988).

Since then Jeff has continued to pour on the Bridges magic on film. Few enjoy such an enduring popularity while maintaining equal respect with the critics. The Fisher King(1991), American Heart (1992), Fearless (1993), The Big Lebowski (1998) (now a cult phenomenon) and The Contender (2000) (which gave him a fourth Oscar nomination) are prime examples. More recently he seized the moment as a bald-pated villain as Robert Downey Jr.‘s nemesis in Iron Man (2008) and then, at age 60, he capped his rewarding career by winning the elusive Oscar, plus the Golden Globe and Screen Actor Guild awards (among many others), for his down-and-out country singer Bad Blake in Crazy Heart (2009). More recently, Bridges starred in TRON: Legacy (2010), reprising one of his more famous roles, and received another Oscar nomination for Best Actor for his role in the Western remake True Grit (2010).

Jeff has been married since 1977 to non-professional Susan Geston (they met on the set of Rancho Deluxe (1975)). The couple have three daughters, Isabelle (born 1981), Jessica (born 1983), and Hayley (born 1985). He hobbies as a photographer on and off his film sets, and has been known to play around as a cartoonist and pop musician.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

- Liam

- No Comments

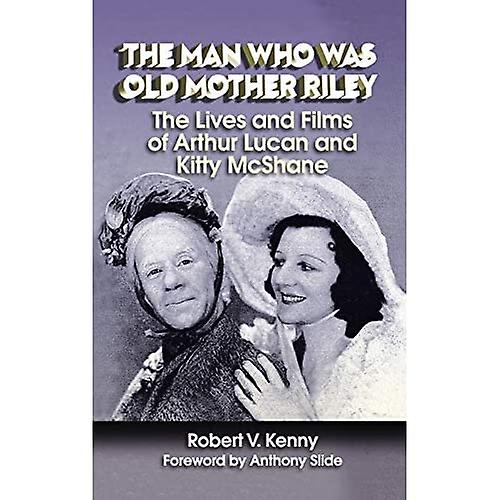

Kitty McShane was part of the famous British double bill “Old Mother Riley and her daughter Kitty”. She was born in Dublin 1897. She was the fourth of seventeen children. In 1913 she married Arthur Lucan (Old Mother Riley). They became a popular music hall act. They began making films together in 1937 with”Old Mother Riley”. Together they made 13 Mother Riley films together. Their off-screen fights were legendary. Kitty McShane did not appear in the final Mother Riley film. Kitty McShane died in 1964. Radio recording of Arthur Lucan & Kitty McShane can be heard here. Very good article on Arthur Lucan & Kitty McShane can be accessed here on the Britmovie website.

- Liam

- No Comments

Gordon MacRae obituary in “Los Angeles Times”.

“In the 30s, Bing Crosby virtually had the field to himself. Over at Warners, Dick Powell also crooned, at RKO Fred Astaire sang as he tapped and at MGM Nelson Eddy gave out in stentorian tones. None of the other male singers made much impression or stayed long. In the 40s, after the success of Frank Sinatra, there was a new influx – Perry Como, Dick Haymes, Andy Russell. Crosby stayed way out in front. Gordon MacRae, also came to movies via radio and records, and he developed into one of the best singing stars – almost as easy as Bing, more animated than Como or Haymes, more virile then was Sinatra of the 40s” – David Shipman – “The Great Movie Stars – The International Years”.

Gordon MacRae was a fine singer who has made an impression in several fine musicals e.g. “Oklaholma”, “Carousel”, “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” and “The Desert Song”. He was born in 1921. In 1948 he made his film debut in “The Big Punch” and his cinema peak was in the 1950’s. He made many fine recordings including several albums with Jo Stafford. Gordon MacRae died in 1986 at the age of 64.

Obituary in “Los Angeles Times”:

Gordon MacRae, the clean-cut, full-throated baritone who triumphed over the alcoholism that threatened a career which peaked with his portrayal of Curly in the film version of “Oklahoma,” died today at Bryan Memorial Hospital in Lincoln, Neb.

He was 64, said hospital spokesman Edwin Shafer, who added that MacRae had been hospitalized since November suffering from cancer of the mouth and jaw and pneumonia.

Although he appeared in several successful stage, radio and television programs, MacRae will best be remembered for two film musicals–“Carousel” and “Oklahoma.” In each he appeared opposite Shirley Jones, and her lilting soprano proved an appealing complement to MacRae’s sonorous baritone.

Father Saw Talent

MacRae was the son of “Wee Willie MacRae,” a singer turned businessman who encouraged his son’s innate talent.

The young MacRae was a page boy with NBC who joined “Horace Heidt and His Musical Knights” as a vocalist in 1941. He had minor roles on Broadway and radio but was drafted into the Army in 1943. After the war he starred on NBC radio on the old “Teentimers” show, but his career didn’t really take off until Warner Brothers signed him to a contract in the late 1940s.

In all he made 25 films including “West Point Story,” “The Best Things in Life Are Free” and “Look for the Silver Lining.”

But by the 1970s his life and his career were in decline because of his drinking.

“I was one hell of a drunk,” he said in 1982, referring to the Lakeside Club in North Hollywood as his prep school for alcoholics. “I used to stand at the bar and try to out-drink Bogey (Humphrey Bogart) and Errol Flynn.”

Couldn’t Remember Lyrics

In 1978, a year after he was unable to sing in concert in South Carolina because he couldn’t remember his lyrics, he entered an alcoholism treatment center in Lincoln.

He lived in Lincoln with his second wife, Elizabeth, until his death because “it reminded me of my hometown” (East Orange, N.J.).

One of his last appearances was in Las Vegas in October, 1982, shortly before he suffered a stroke.

It was a benefit for the National Council on Alcoholism, which MacRae adopted as a favored charity after his own recovery.

He referred to the occasion as “our third annual Follies Berserk” but on a more serious note reflected how “you hit bottom, then you make up your mind. I’m sober 23 months now.”

His obituary in “The Los Angeles Times” can also be accessed here.

- Liam

- No Comments

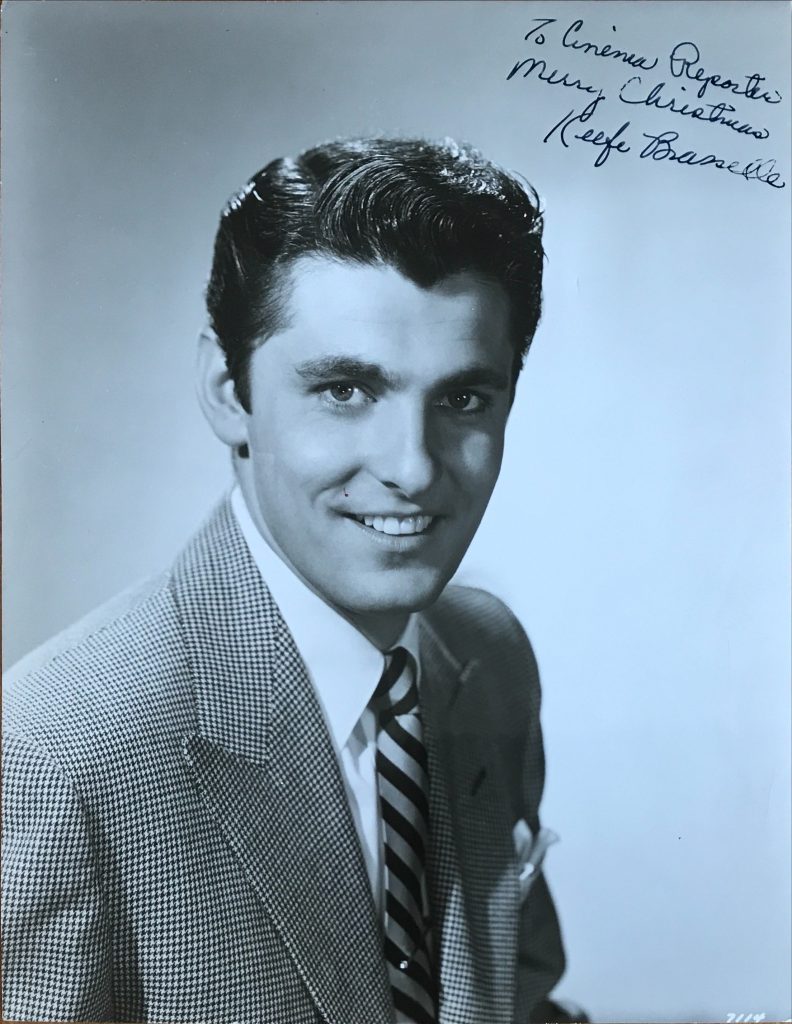

Keefe Braselle was born in 1923. He made a name for himself in playing the title character in “The Eddie Cantor Story”. His other film performances include “A Place in the Sun” and “The Streets of Sin”. He died in 1981. Some comments about Keefe Braselle and his working relationship with Jack Benny can be found here.

“New York Times” obituary:

Keefe Brasselle, a film actor known for his leading role in ”The Eddie Cantor Story,” died last Tuesday in Rancho Los Amigos Hospital in Downey, near Los Angeles. He was 58 years old and had been hospitalized several times during the last few years for a liver ailment. During the early 50’s, Mr. Brasselle was considered a promising talent, appearing in ”A Place in the Sun,” ”Bannerline,” ”Skirts Ahoy,” ”Three Young Texans” and ”Battle Stations.” He gained prominence in 1953 in his first leading role, as Cantor, the song-and-dance man. An effort by Mr. Brasselle to become a television producer was short-lived. Three series he produced and sold to CBS-TV in 1964 – ”The Reporters,” ”Baileys of Balboa” and ”The Cara Williams Show” – were canceled in their first season. In 1968, he published ”The Cannibals,” a thinly disguised expose of controlling figures in the entertainment industry and behind-thescenes intrigue

- Liam

- No Comments

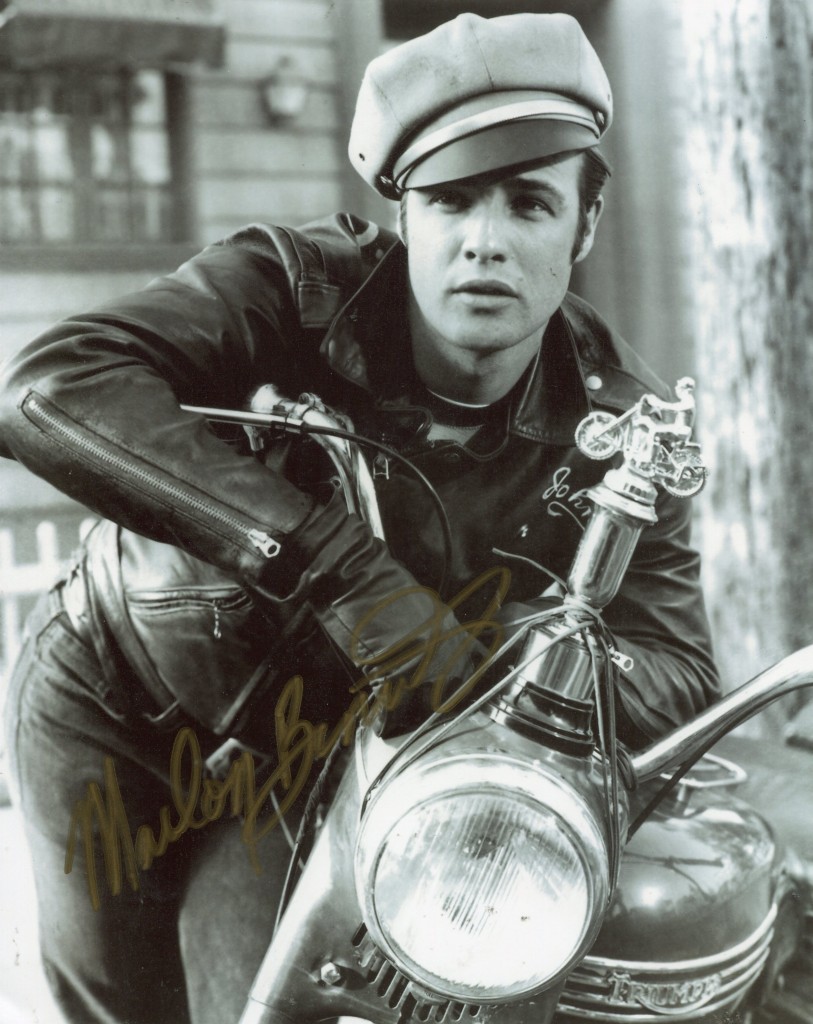

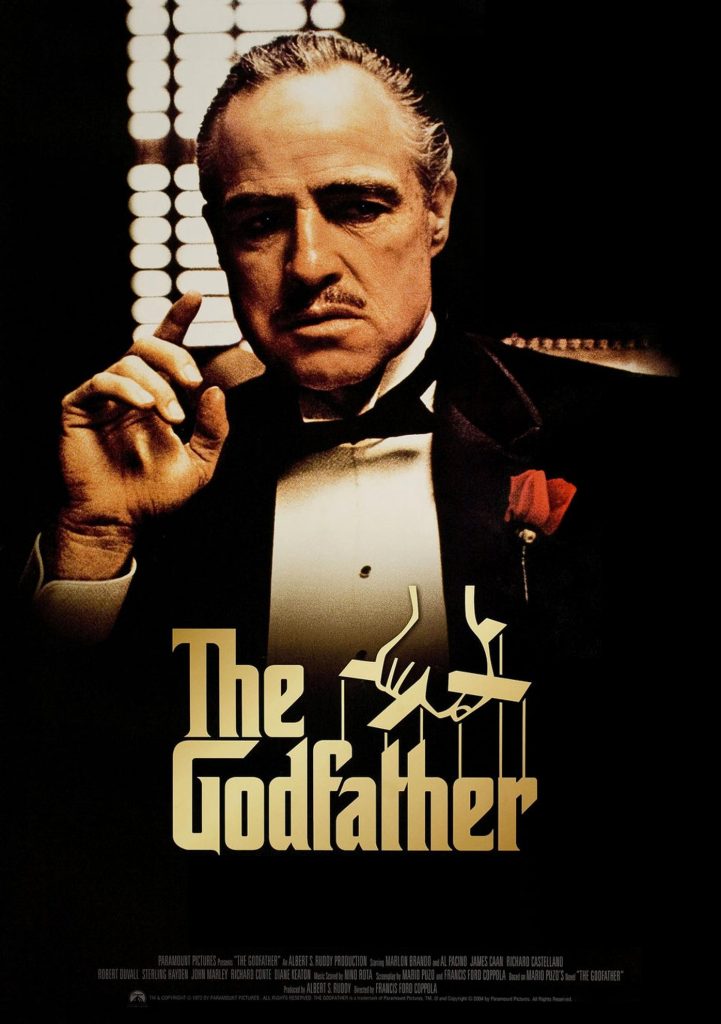

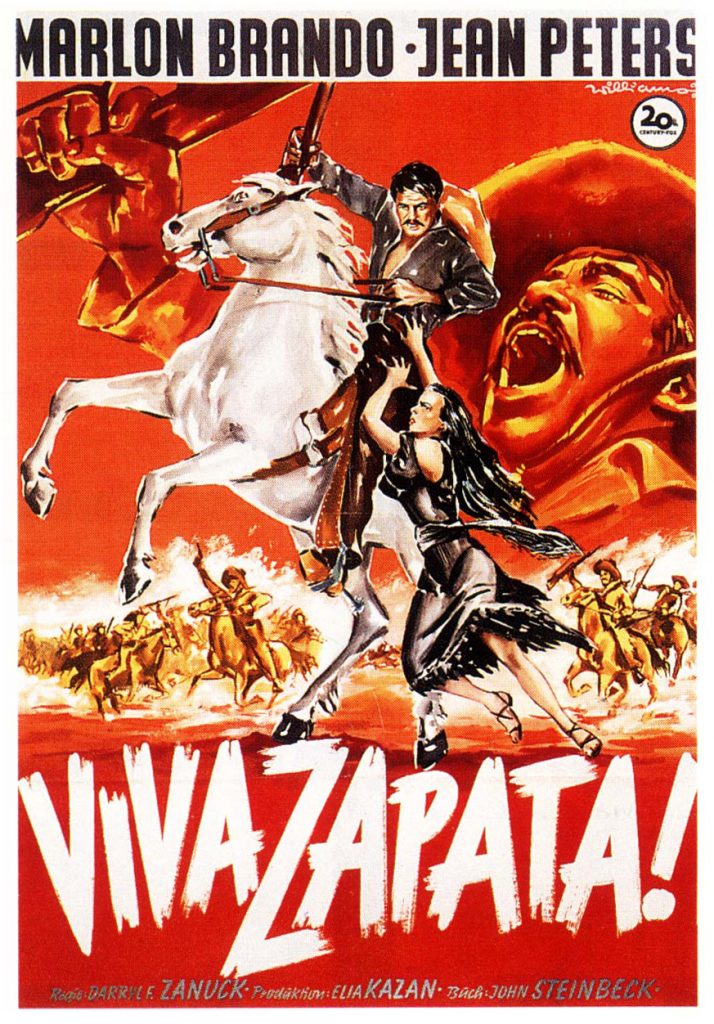

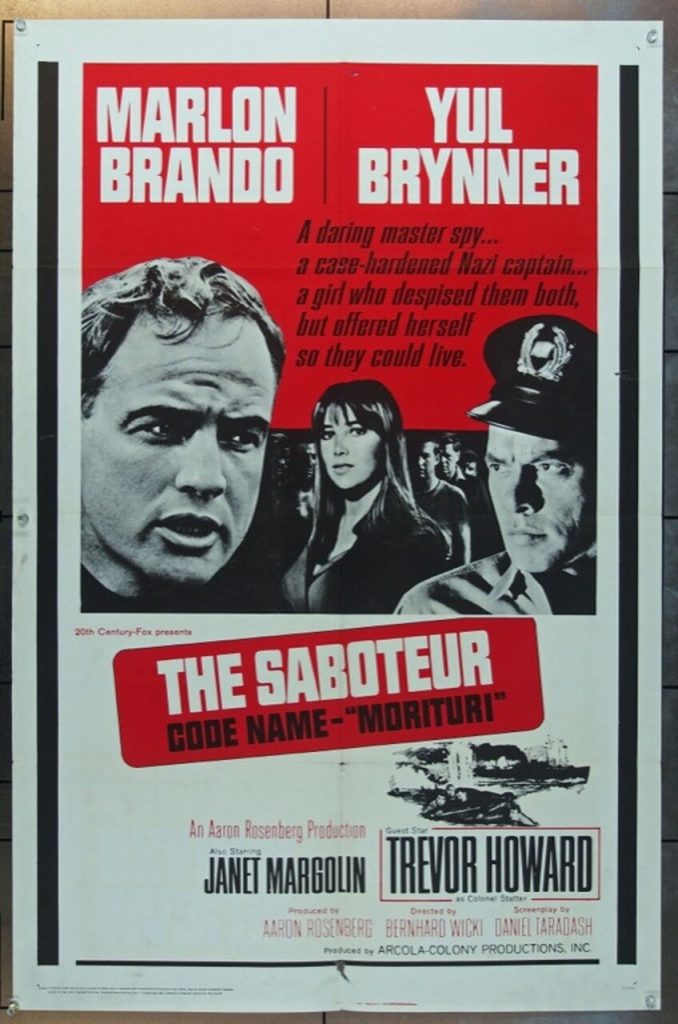

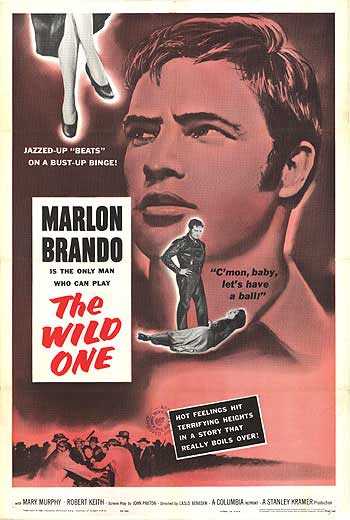

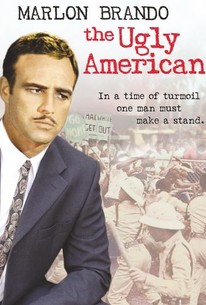

Marlon Brando obituary in “The Guardian” in 2004.

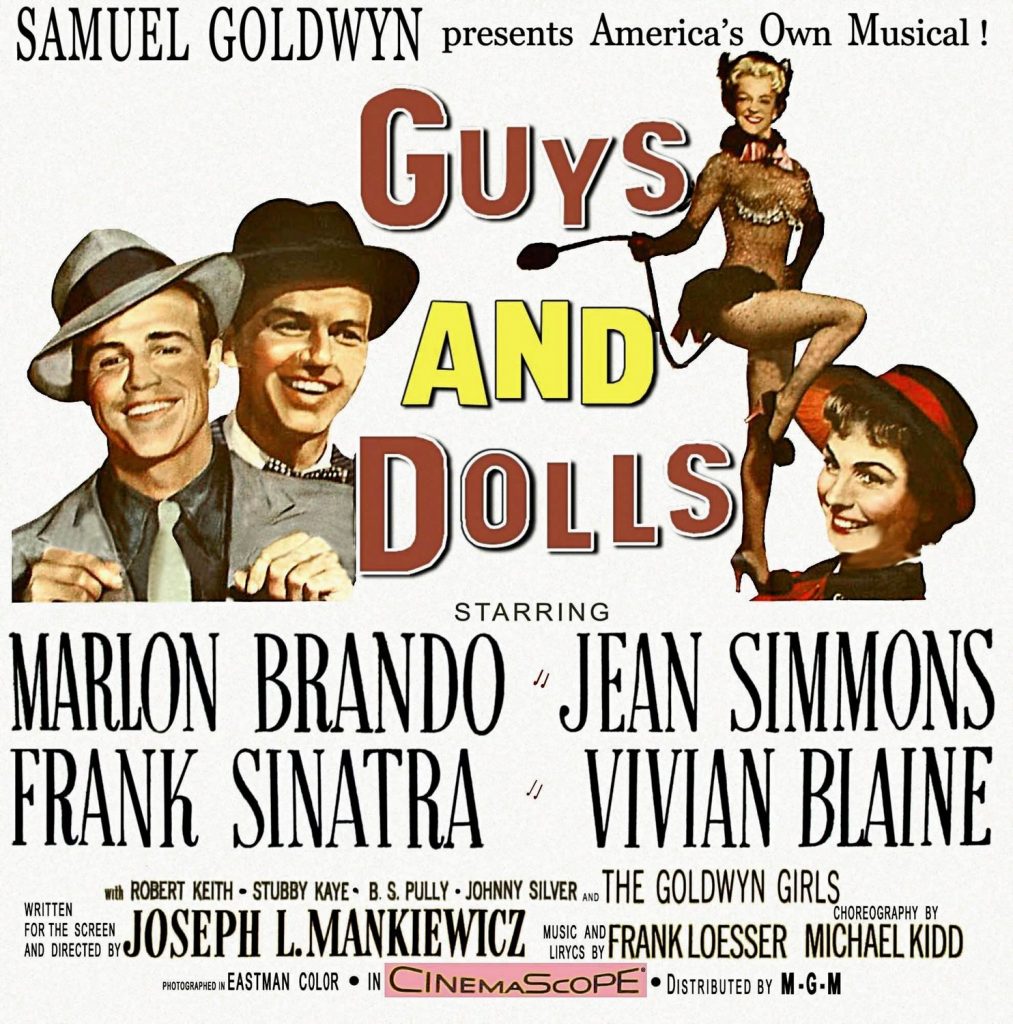

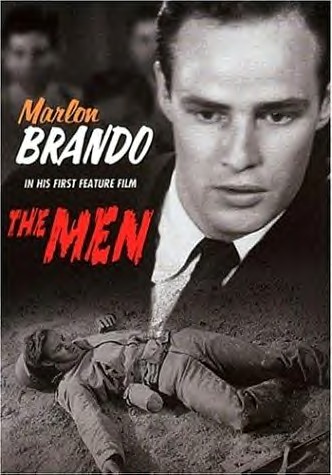

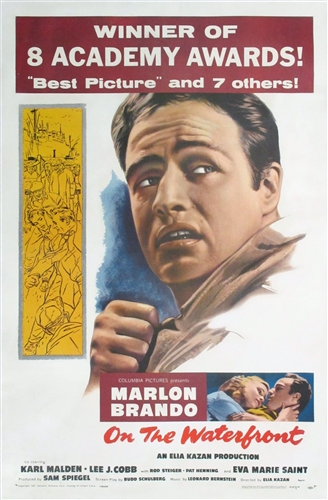

Marlon Brando is regarded as one of the best cinema actors to grace the screen. He was born in 1924 in Omaha, Nebraska. His sister Jocelyn had commenced an acting career. Marlon went to Broadway in his late teens. He became the toast of Broadway for his part as Stanley Kowaski in Tennessee William’s “A Streetcar Named Desire”. He made his film debut in Fred Zinnemann in “The Men” in 1950. He repeated his Broadway performance in the film version of “Streetcar” in 1951 with Vivien Leigh. He won the Oscar twice for “On the Waterfront” and for “The Godfather”. His other fine performances include “Guys and Dolls”, “Desiree”and “Sayonara”. Marlon Brando died in 2004.

“Guardian” obituary:

He was only an actor, and as he pointed out actors are no more than dishonest entertainers, frauds, pretenders, liars – he could be relentlessly hard on himself. But was it then any defence that he acted so seldom, that he had deserted the stage he had himself brought to life, or that he had come to regard movies with the hurt feelings of a Kong, hiding in his lair, unwilling to make a cheap spectacle of himself for those exploiting showmen? Why trust acting or films, he sometimes said, for these things emerge from the pit of our corruption. Not that he had made himself, as an alternative, a model of quieter, domestic virtues. By his own gloating, but tortured, confession, he was a career womaniser, a glum joke as a husband, and sometimes pitiful as a father. Anything else? Why, yes, of course, he was a hulk, a wreck of obesity and self-indulgence, a hideously fat man – he who once had been so beautiful he altered our idea of maleness.

It can be no surprise that, at the age of 80, Marlon Brando is dead. Rather, it must speak to his will and need that he lived so long, so out of shape and humour. And he was also so resentful of the world, and so scornful of himself, that it is hard to measure lost happiness. The man who published his autobiography Songs My Mother Taught Me, in 1994, was already cynical to the point of nihilism, a tease and a trickster, yet always most mocking of himself. To read that book was to be disturbed at how little he liked himself, no matter the conventional armour of vanity in a grand actor. He could be very vain and very foolish – in part because of the opening they provided for self-loathing later. He did his book for money, and then he ranted against people who were so mercenary. But he needed money for his broken family – and he had never made or kept as much as lesser actors – one son in jail, another child on her way to suicide. A godfather in legend, he was confused in life. You could hear the howls of grief between the lines – yet he had denied himself, and us, a Lear. And Falstaff, and Vanya, and so on.

Yet he was the American actor of modern times, and of the second half of the 20th century, someone who was regularly placed in that small circle of the finest actors, the most potent and dangerous actors who could take a role and their audience into emotional territory that no one had anticipated. What was most remarkable about Brando was that unquestioned eminence rested on so few films and on just one historic stage performance.

Born in Omaha, Nebraska – the state that produced Montgomery Clift, Henry Fonda and Fred Astaire – he was only 23 when he brought Stanley Kowalski to life in A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947. It had not been a comfortable life. He was the child of two drunks, the father domineering, miserly, a womaniser but unloving, the mother creative but weak, broken and helpless. He had grown up feeling unloved and untrusting, hating authority, strong men and needy women. Yet it was far from the worst life imaginable, and it would be wrong to see the youth as wounded. There was, from the outset, a rebelliousness, an ego and an intricate self-pity determined to be wronged. And in that wronging he found energy.

Other people could only fall in with their casting in his drama. For though Brando worked sparingly, he was an actor or a player in his own life, a chronic instigator of intrigues, and a character who lived to find a way of being hostile or difficult with others.

He was educated at Libertyville high school in Illinois and then sent to Shattuck Military Academy. There he was expelled for indiscipline – that had been his plan. He went to the Dramatic Workshop of the New School for Social Research in New York in 1943, and studied with Stella Adler, yet he never filled the role of a determined, dedicated actor. On the contrary, he boasted of the chanciness of his career, his laziness, and a deep indifference to acting as art or vocation. But he got parts in I Remember Mama (1944), and Truckline Cafe and Candida in 1946.

He was amazingly beautiful – there is no other way of saying it, or denying its vital thrust in what happened. He had huge eyes, a wide, deep brow, an angel’s mouth, with the upper lip crested. And he could speak softly, like breathing, so the mouth scarcely moved. But he was as male as a wild animal; hunky, husky, sensual, and incoherent or rhapsodic, depending on which style worked best with the young woman of the moment.

Irene Selznick, the producer of A Streetcar Named Desire, had thought of John Garfield or even Burt Lancaster for Stanley. But she had seen Brando in Ben Hecht’s A Flag Is Born in 1946 and had been “galvanized by his power … however risky, he was bound to be interesting”. Elia Kazan, the director, wanted Brando because he knew the actor’s radiance would keep Stanley from being just a villain, the trampler upon Blanche Du Bois’s fragile bloom.

It was left to the playwright, Tennessee Williams, to decide. Brando went to see Williams who was living on Cape Cod. When he got there, both the electricity and the plumbing were out. The actor repaired them both, and then did a reading, with Tennessee taking the other parts. It was 10 minutes before they called Kazan and Selznick and told them yes. Williams wrote to his agent, Audrey Wood: “It had not occurred to me before what excellent value would come through casting a very young actor in the part. It humanises the character of Stanley in that it becomes the brutality or callousness of youth rather than a vicious older man. I don’t want to focus guilt or blame particularly on any one character but to have it a tragedy of misunderstanding and insensitivity to others. A new value came out of Brando’s reading which was by far the best reading I have ever heard. He seemed to have already created a dimensional character, of the sort that the war has produced among young veterans.”

There was a sub-text, too, for why Streetcar worked so well. Williams was gay. There was a latent sense in which Blanche was a male surrogate, the spirit of refinement and gentility, confronted by a far more brutal and modern male force. But Kazan was a devout heterosexual, and a director of the new breed that needed to find himself in the work. So he identified with Brando’s Stanley and a crude upstart vitality reducing the pretentious lady to his own level. The play surpassed its text in production, and in some profound way 1947 was ready for every fantasy that was appealed to.

Because of the special details of casting and production, Streetcar was revealed as one of those especially American works, in which energy encounters refinement, and in which the role of gender was suddenly complicated. It was an early glimpsing of a bisexuality that many people were as thrilled by as they were alarmed. But no one quite knew what was happening that first night – December 3 1947 – except that they had been poleaxed.

The audience stood. The curtain calls lasted half an hour. Jessica Tandy played Blanche Du Bois, and she was universally admired. But Brando changed the culture.

As Kazan saw it, Brando had changed the play – audiences liked Stanley more or as much as Blanche (it was only later that Streetcar became a play about Blanche). A kind of rutting force was let loose, a feeling of native American force. Brando was seen on stage half-naked (he had a flawless torso then), discarding a sweaty T-shirt, alive, urgent, unruly and golden. People of both sexes fell for him at the same moment as a classical male persona had been explored or layered, and only Brando could have held the human beast and the brooding angel in balance. It began to be possible for the American hero to be beautiful, and not just handsome.

That insurrectionary actor never again worked on stage once the heady run of Streetcar was over. There would be no Hamlet, no Coriolanus, no Antony (on stage). This was an actor who never did Chekhov or O’Neill – over the years, imagine him in three of the roles from Long Day’s Journey Into Night, or why not four? He never did Pinter, Hare, Shepard or Mamet. Never again elected to be there pretending, just a matter of a few feet away, in the same electric space and air as the audience.

Why? He was not a heartfelt actor, he said, and he was certainly not charitable. There was a mean streak in Brando, a cunning country boy’s lust for money and fame and adulation – all the poisons he would turn from in horror once he had tasted them. So he went to Hollywood and became a movie actor – it was what Stanley would have done; it was also the quicker way for someone who wanted to despise himself. In 1950 came The Men.

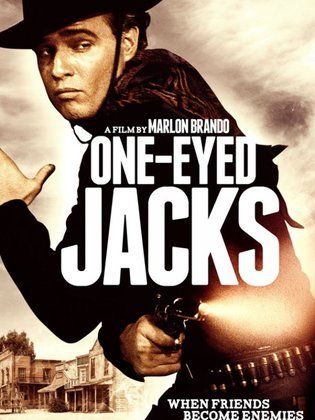

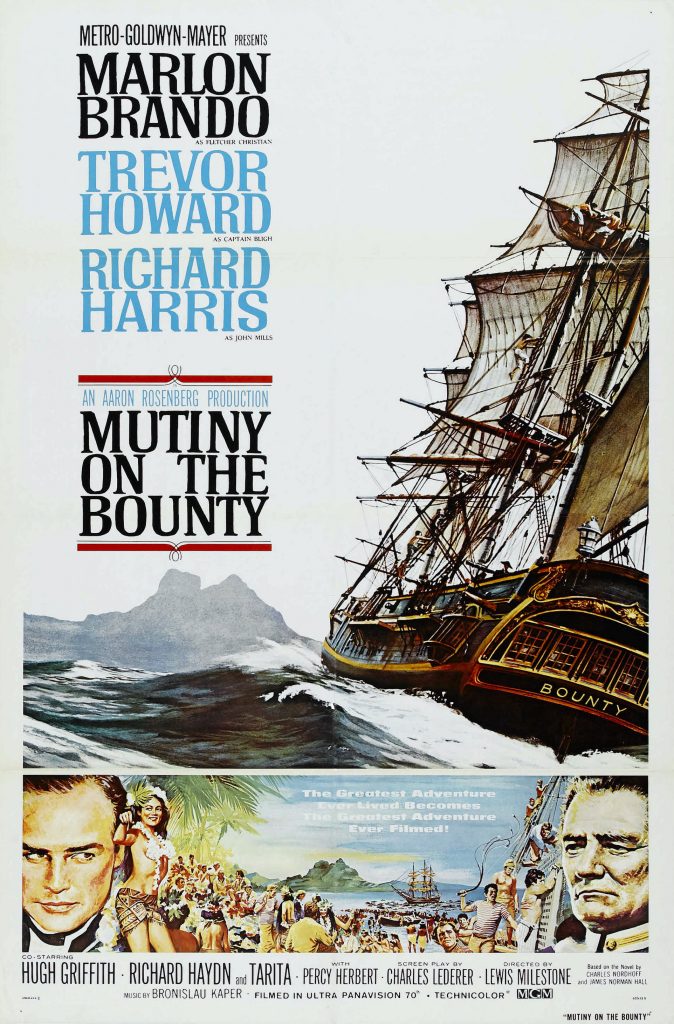

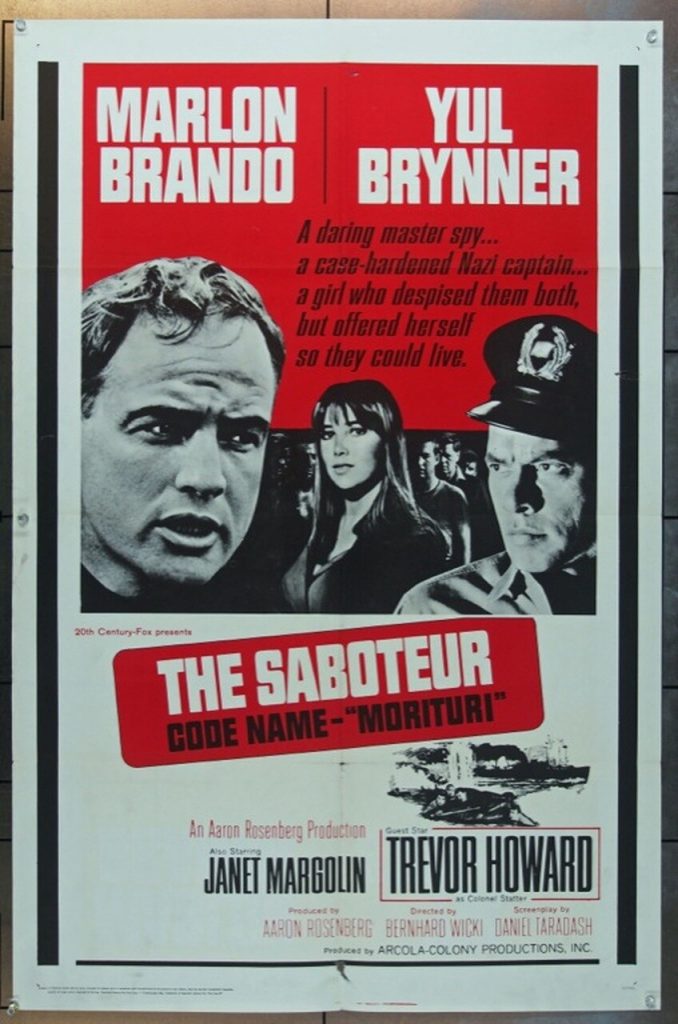

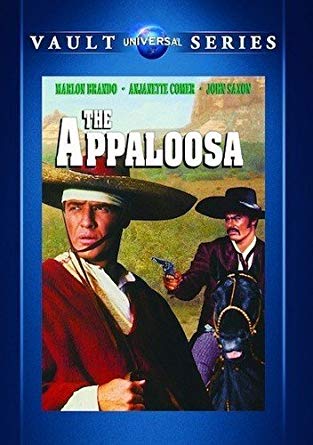

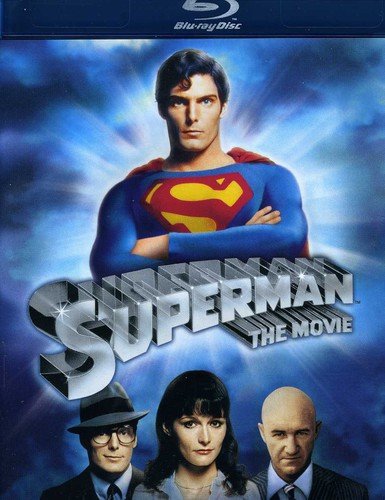

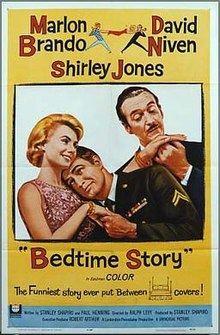

Of course, that was far from ruin. But one might as well say, without apology or explanation, that most of the film work he did was shameful junk, ill-chosen, slapdash and devoid of soul. Get ready, it is a long list and included: Désiree (1954); The Teahouse Of The August Moon (1956) Sayonara (1957); The Young Lions (1958); Mutiny On The Bounty (1962); The Ugly American (1963); Bedtime Story (1964); The Saboteur Codenamed Morituri (1965) Appaloosa (1966); A Countess From Hong Kong (1967); Candy (1968); The Night Of The Following Day (1969); The Nightcomers (1971); Superman (1978); The Formula (1981); Christopher Columbus (1992). That is a lot of rubbish to clean out in the search for gold – and it must be pointed out that Brando, quite early on, had unusual power in determining his own projects.

He is the great actor, and the idol of a generation of actors who have been directors, producers and the arbiters of their own careers. Brando directed once – on One-Eyed Jacks (1959) – before boredom and sourness took over, but seldom had the patience, the stamina or the courage to be master of his own fate. Instead, he liked to be seen as the victim of a malign, stupid system, for that came to the aid of his tricky mixture of indolence, disbelief and hypocrisy. Still, a lesser actor – Paul Newman, say, only a few months younger – built up a far more consistent body of work than Brando dared.

That said, there are films, or passages from films, that explain the way so many people felt – not least Newman, Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, Dustin Hoffman, Al Pacino, Robert De Niro … and so on, to the bottom of the page. Nearly every American actor since has moved through his own work mindful of Brando’s record and potential.

He was doing pictures early, in an age when William Holden, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster and John Wayne were the rage. Their style was clearcut, confident and unambiguous. So it meant all the more that Brando’s acting was made, palpably, out of indecision – in pauses, aborted gestures, frustrated eloquence, and a feeling of the enormous, untidy accumulation of experience that could not just deliver on “Action!” He was laughed at for this: comedians did Brando impersonations. But the new attitude – Method or beyond Method – was the future. Every young actor, from James Dean on, and every rock singer, from Elvis down the line, was affected by Brando’s pent-up inwardness.

He was a paraplegic in Fred Zinnemann’s The Men – the first role that defined his affinity with frustration. He reprised Stanley in Kazan’s film of Streetcar (1951) – with Vivien Leigh instead of Tandy, in a censored version, but still our nearest to a record of 1947. He was the hero in Viva Zapata! (1952), and a fine, if unprofound, Antony in Joseph Mankiewicz’s Julius Caesar (1953).

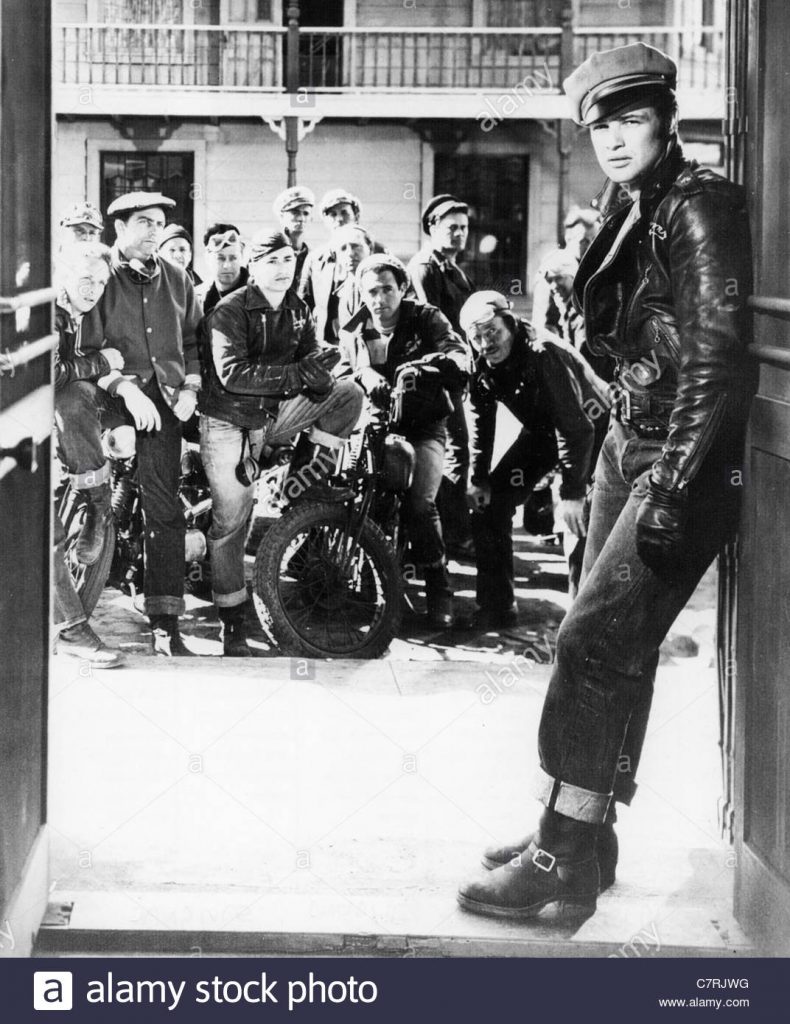

John Gielgud (Cassius) beheld him, and then invited Brando to come to England for a season of plays they would do together – Brando declined, and lived on to see the noble creative vitality of Gielgud, working, working. Brando was Johnny the biker in The Wild One (1953), a very camp figure, a gay icon, but a sulky kid who, when asked “What are you rebelling against?”, knew young America’s cool answer, “What have you got?”

Then, in 1954 he was the ex-boxer, the one who could have been a contender, in On The Waterfront, that curious apologia for informing made by Kazan and Budd Schulberg after they had testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Brando got an Oscar for that film after being nominated four years in a row – for Streetcar, Zapata, Julius Caesar and Waterfront. The film doesn’t wear too well. Too much of it looks like Actors’ Studio guys pretending to be dockers and lowlifes. But Brando’s deliberately battered beauty was as poignant as the self-discovery in a dumb kid that he had let himself be used too often.

That was his first period, his youth, and it is fascinating to note that it ended as James Dean arrived on the scene. They met, warily. Dean was younger, hungrier – and Brando had been offered the role that Dean played in East Of Eden; indeed, Kazan had wanted Brando and Montgomery Clift as the brothers. Brando felt older, more experienced, both tired and bored by the fame of being an idol. He diversified – that’s where the trouble started. He was amusing doing Sky Masterson in Guys And Dolls (1955), where he sang and danced like an old boxer anxious not to rip his new suit. But too many of the films were beneath him, and too many of the attempts to dress up and do an accent were patronising.

He was superb, with Anna Magnani and Joanne Woodward, in Sidney Lumet’s The Fugitive Kind (1960) – from Tennessee Williams again – a truly neglected picture. In One-Eyed Jacks, he could not see beyond the mean-spirited vengefulness of the story; he shot miles of footage and gave up on the editing. Some have made a cult of the film, but it is inert and pretentious.

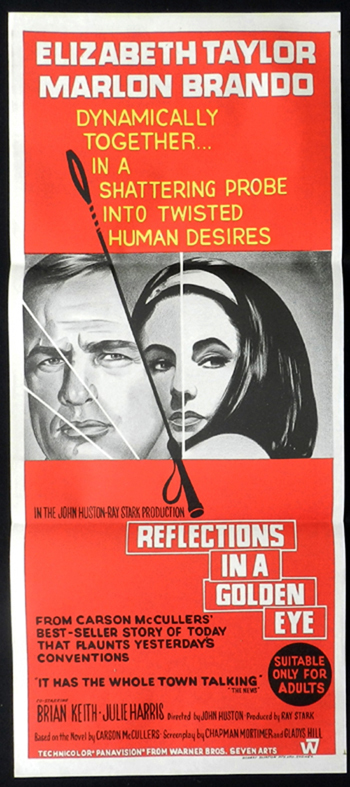

And so his career became a mystery. There were inexplicably wasteful projects, and then suddenly the authentic actor was back – in The Chase (1966), Reflections In A Golden Eye (1967), or in 1969 in the very adventurous Burn! (also released as Queimada). That picture was made by Gillo Pontecorvo in Latin America, and it cast Brando as an English adventurer in the service of corrupt imperialism. It was a picture made out of political conscience and in defiance of Hollywood, and it is well worth pursuing.

By 1970 or so, the man was a mess and a figure sinking beyond the cultural horizon. He lived a good deal in Tahiti. He had acquired three marriages – to Anna Kashfi (Anglo-Indian), Movita Castenada (Mexican) and Tarita (Tahitian). There were many more affairs, and he was the father of at least 11 children. He liked to seduce married women, then abandon them. He would humiliate husbands and sometimes he exulted in a kind of mutual sexual degradation. Equally, there were women who said he was a magical lover and an enormous influence on their lives. There was also the feeling that as an actor he had become so unpredictable and wayward as to be out of control.

Then in two years, close to the age of 50, he grabbed at work so extraordinary that he secured his reputation – and made his subsequent vanishing all the more tragic. He did two films, one entirely conventional, the other so radical it risked being banned. In The Godfather (1972), he was Vito Corleone, that old standby – a master criminal and the rock on which family is built. It was not a difficult part for him, once he had got the look, the voice, and the cotton wool in his mouth. But the film was a smash hit (his first such success) and Vito was a model of the new American ambiguity: a killer, a pioneer of criminal method, and a man with a sense of love, duty and respect. His boys and followers – James Caan, Al Pacino, Robert Duvall, John Cazale – attended to him like disciples with their master. He won a second Oscar and sent an alleged Apache maiden to refuse it, with a long speech about American abuse of native Americans. The maiden wore buckskins and false eyelashes; it turned out she was some kind of actress.

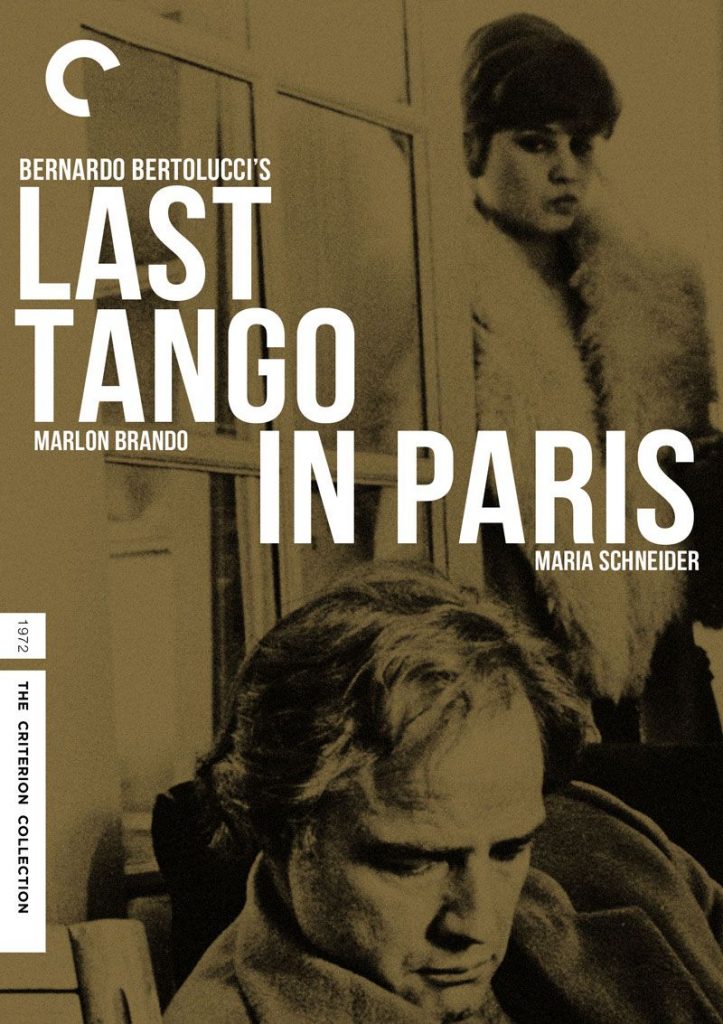

And then he agreed to do Last Tango In Paris (1972) for Bernardo Bertolucci – the last dissolute, shabby, vile act of the former angel, a role that mined his own past (because he let it), that depended on his own great fascination with sex and its power, as well as his tormented feelings towards women. And he did it casually, without the vibrato of “this is hugely dangerous and difficult”. If anyone doubts Brando’s greatness, see this film and absorb the sheer absent-mindedness of the performance – he is so deeply into his role that he exposes only a fraction of the man’s life. He seems not on show, yet we see more of human nature than film has ever prepared us for. In Last Tango, the “has-been” suddenly appeared 10 miles ahead, not even bothering to smile at all the rare, new places he had been. The film is lacerating, but Brando’s pain in character is subdued by the achievement of the acting. Yet the whole thing was sly and subversive, for it whispered, see, see what you have been missing.

The missing became greater still after Last Tango. He worked far less often. He began to put on fearsome weight. He let it be known that the world and its audiences hardly deserved him. But he made grotesque monetary demands for the nonsense of Superman.

And in a film like The Missouri Breaks (1975) – with Jack Nicholson, the latest next Brando – he kept changing his character, as if to ridicule such things. The result was hilarious – we have always seen too little of Brando the comic – but neither Nicholson nor director Arthur Penn could keep up with his whims.

Equally, on Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1977), Brando added to the hideous burdens of that production by imposing himself as a terribly overweight and under-prepared actor, determined to philosophise about the part and the picture, ready to embark on profuse improvisations and diversions. The result was not pretty or effective – and it was less than generous to the director who had made The Godfather with him.

He made four films then in 15 years, with only the gentle, amusing The Freshman (1990) and Don Juan De Marco (1994) in the plus column. In the latter, he was a sleepy, dreamy psychotherapist fascinated by Johnny Depp’s claim to be Don Juan, and brought back into merry contact with his wife, played by Faye Dunaway. Though a love scene between them was played in near dark, there was little attempt to mask Brando’s bulk, and every sign of his abiding skill.

But his family life was chaotic and destined for the courts and the tabloids. He gave occasional interviews in which he sneered at the process and seemed to glory in his own monstrousness. When he came to write his autobiography, he remarked publicly on the idiocy of publishers paying so much money – and he even had a plan once to have several women from his life do a chapter each, over which he would preside as silent, taunting pasha.

The autobiography is neither helpful nor appealing, though its account of his early years is fresh and intriguing. Peter Manso published a very lengthy biography, Brando (1994), that gave all too rich a portrait of the ugly manipulation of much of his life. Will there ever be a book that “explains” the man? I doubt it. He was a tragedy of his own wilful, self-abusive resolve. He was a complex masquerader in life’s unwinding and that form challenged him so much more than the texts for plays or films. There might one day be a great novel founded on a figure like Brando. But there is reason to suspect he preferred to leave mystery, wreckage and a confounded public. In all of which he succeeded.

Acting does date. It is already a cause for perplexity that John Barrymore was once passionately regarded as the greatest of American actors. Brando’s Method persona was parodied from the outset, and his true Stanley is now “remembered” by very few people. But we will have The Men, Zapata, On The Waterfront, The Fugitive Kind, The Chase, The Godfather, Last Tango … it is enough, I suspect, for him to become as representative of cinema as Garbo, Chaplin and Mickey Mouse. And as the travail and melodrama of the awkward life passes, so we can look at the movies and recall that we were young, once, when Marlon Brando was doing such things. It was often veiled, supercilious and sinister, but on screen he made us an offer we couldn’t refuse.

· Marlon Brando, actor, born April 3 1924; died July 1 2004

His obituary by David Thompson in “The Guardian” can be accessed here.

- Liam

- No Comments

Sites of Interest

These are some of my favourite film websites. They are a fantastic resource for any film buff.